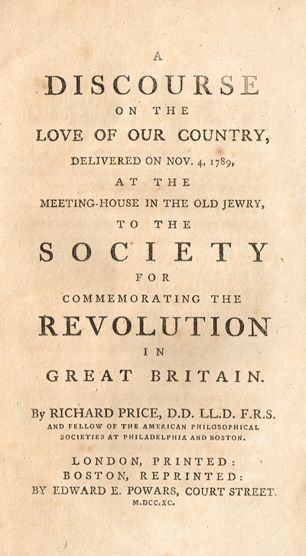

Excerpts from Richard Price’s A Discourse on the Love of Country, 1789

Our first concern, as lovers of our country, must be to enlighten it. Why are the nations of the world so patient under despotism? Why do they crouch to tyrants, and submit to be treated as if they were a herd of cattle? Is it not because they are kept in darkness, and want knowledge? Enlighten them and you will elevate them. Show them they are men, and they will act like men. Give them just ideas of civil government, and let them know that it is an expedient for gaining protection against injury and defending their rights, and it will be impossible for them to submit to governments which, like most of those now in the world, are usurpations on the rights of men, and little better than contrivances for enabling the few to oppress the many. Convince them that the Deity is a righteous and benevolent as well as omnipotent being, who regards with equal eye all his creatures, and connects his favor with nothing but an honest desirc to know and do his will; and that zeal for mystical doctrines which has led men to hate and harass one another will be exterminated. Set religion before them as a rational service, consisting not in rites and ceremonies, but in worshipping God with a pure heart and practicing righteousness from the fear of his displeasure and the apprehension of a future righteous judgment, and that gloomy and cruel superstition will be abolished which has hitherto gone under the name of religion, and to the support of which civil government has been perverted. Ignorance is the parent of bigotry, intolerance, persecution, and slavery. Inform and instruct mankind; and these evils will be excluded.

[. . .]

Happy is the scholar or philosopher who at the close of life can reflect that he has made this use of his learning and abilities: but happier far must he be, if at the same time he has reason to believe he has been successful, and actually contributed, by his instructions, to disseminate among his fellow-creatures just notions of themselves, of their rights, of religion, and the nature and end of civil government. Such were Milton, Locke, Sidney, Hoadley, etc. in this country; such were Montesquieu, Fenelon, Turgot, etc. in France. They sowed a seed which has since taken root, and is now growing up to a glorious harvest. To the information they conveyed by their writings we owe those revolutions in which every friend of mankind is now exulting. What an encouragement is this to us all in our endeavors to enlighten the world? Every degree of illumination which we can communicate must do the greatest good. It helps to prepare the minds of men for the recovery of their rights, and hastens the overthrow of priestcraft and tyranny. In short, we may, in this instance, learn our duty from the conduct of the oppressors of the world. . . .Remove the darkness in which they envelope the world, and their usurpations will be exposed, their power will be subverted, and the world emancipated.