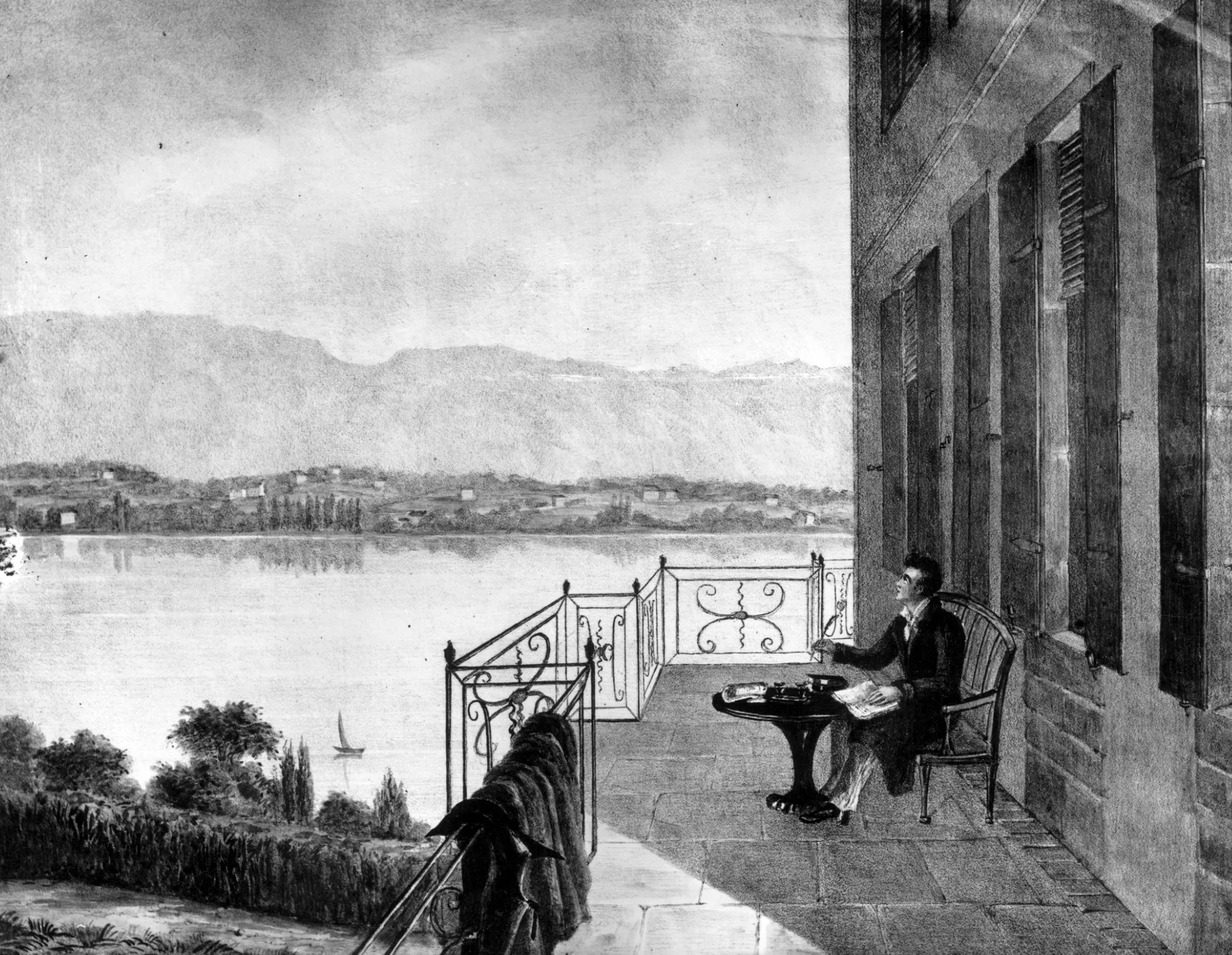

Byron at the Villa Diodati (c. 1816)

St. 1-2 Narrator’s Address

[1] farewell to England and to a beloved daughter; immersion in the unknown

[2] contradictory position of the speaker: “rider” or “weed”?

St. 3-7 Harold’s Creation

[6] the poet asserts that life is only interesting in the act of creation

St. 8-16 Delineation of Harold as the Byronic Hero / Not incidentally mirrors the experience of the narrator in stanza [4]

[9] enchained; [10] “guarded coldness” but in wonder of Nature; wandering now with a “nobler aim” [11]; a movement between Nature and Society [13 and 14]

[14] “clay” and “spark” imagery

[15]”falcon with a clipp’d wing”

St. 17-20 Description of Waterloo

[17] the only mark of “Empire’s Dust” is the unnatural fertility caused by spilled blood

[18] Napoleon linked to his emblem of the “eagle”

[19] the danger of restoring the monarchies; perhaps the “lion” as been exchanged for the “wolf”

St. 21-28 Evocation of the Battle Scene

A lengthy and climatic description of the moments leading up to the battle (the irony of the soldiers attending a ball when the call to battle is issued; again the movement between life and revelry and death and battle)

[25] a real elevation of battle

[27] the glories of battle immediately undercut by a description of nature;

[28] the heroism of man finally ends of as “Clay” (final 3 lines)

St. 29-35 An elegy mourning the loss of life / simultaneously functions as a metaphor for his own lost hope

his cousin, Major Howard, becomes another type of the Byronic hero; in this case, losing life through action

St. 36-45 Meditation on Napoleon

Qualities of Napoleon are like those of the Byronic hero: “daring made thy rise as fall”(36: l.321); “He stood unbowed beneath the ills upon him piled” (39: l. 351); “There is a fire /And a motion of the soul which will not dwell / In its own narrow being, but aspire / Beyond the fitting medium of desire” (42: l. 371

[36] the danger is in the “extreme[s]” of Napoleon’s character

[43] through [45] is more of a general meditation on how fame turns “men mad” [43]

St. 46-51 Nature’s Superior Power over Man-made structures [Movement from Belgium to Germany]

[46] an explicit turn away from a consideration of “human nature”; Harold in nature looking at the ruins of a once powerful castle

[47] “All tenantless, save to the crannying wind” and “the bleak battlements shall bear no future blow”

St. 52-55 Harold’s thoughts on Lost Love

Here we have an example of Harold’s role throughout CHP, that is, he charts the “personal” experience with the landscape, does not take on the role of cultural critic

Harold’s experience of the battlefield leads to an internal meditation about the allure of love.

Is this a way to counter man’s failure on the battlefield? Another opportunity to experience “life”? [Inset ballad “sung” by Harold: note stanza change].

St. 68-75 Justification for Solitary Exile — One with Nature [Movement Towards Switzerland]

[68] “Lake Leman woos me with its crystal face”

[69-71] rejection of the world “contentious” for the lure of “earth”

[72-75] One of the narrator’s moments of union with nature; a type of consummation of the desire expressed in [68]

[73] a reappearance of the “falcon” theme: “On delighted wing / Spurning the clay-cold bonds which round our being cling”

[75] mixes with Nature as he had mixed with the creation of Harold [6]

St. 76-84 Description of Rousseau

[76] one of those sudden shifts to the things and men of the world: “On One, whose dust was once all fire” (719). Rousseau yet another quester after Fame and Truth.

[81] The danger (and power) of writing which inspires revolution

[83] But ” What deep wounds ever closed without a scar?”

St. 85-97 Natural / Poetic Union and Another Turn toward Nature

[85] “Clear, placid Leman! thy contrasted lake, / With the wild world I dwelt in, is a thing / Which warns me, with its stillness, to forsake / Earth’s troubled waters for a purer spring” [89] “All is concentered in a life intense” and [90] the “feeling infinite”

[92-96] attempts to match the sweep of the storm across the horizon with his verse

[97] the impossibility of ever speaking the “one word”

St. 98-108 Meditation on the Works of Man: Rousseau, Voltaire, and Gibbon

in response to his failure to speak “the one word Lightning” Byron offers up models of the writer as iconoclast challenger of excepted “truths”

St. 109-118 Conclusion; ends of poetry

Is poetry merely a “wile” or is it the means of immortality?

[109] Explicitly notes his consistent movement between “man’s works” to those of “His Maker’s”

[110] Movement toward Italy; already restlessly moving beyond the Alps

[112] characterizes his poetry as “a harmless wile”; does not care about immortality

[113-114] Statement of the exile’s mind standing alone, implicitly nullifies the previous stanza’s modesty

[115 to the end] returns to the beginning of the poem and addresses Ada once more