As a recovering English major and current English graduate student, I certainly have my fair share of novels, poetry collections, and plays that I have extensively marked up for class. While many of these are Extremely Smart and Insightful annotations, some margins of my books contain silly doodles of animals, goofy faces, and absentmindedly drawn patterns. I know I am not alone in doing this – I’ve seen plenty of my classmates doodling on their notes and books during class, and I’m willing to bet some people reading this blog post can relate. Now to pose a slightly unnerving question – what if in, say, three hundred years, a group of college students has gotten their hands on your copy of The Canterbury Tales and get to analyze your little doodles? Kind of weird to think about, right?

Well, sorry to whichever past students used TM 942, a manuscript copy of the great Roman poet Juvenal’s Satires, because I am that evil graduate student introducing and analyzing their doodles – among other things, of course. TM 942 was created in northern Italy in the 15th century, likely between 1460 and 1480, and has extensive evidence of use including by students. TM 942 is an intriguing surviving copy of the famous classical text, something which is immediately apparent even at first glance. The binding – wooden boards covered in dark tooled leather – is actually the original Italian binding, with some modern repairs (a reinforced spine and two new metal clasps). The detailed tooling on the leather is almost entirely faded after over five hundred years of use, but considering the manuscript is entirely intact, the binding has done its job well!

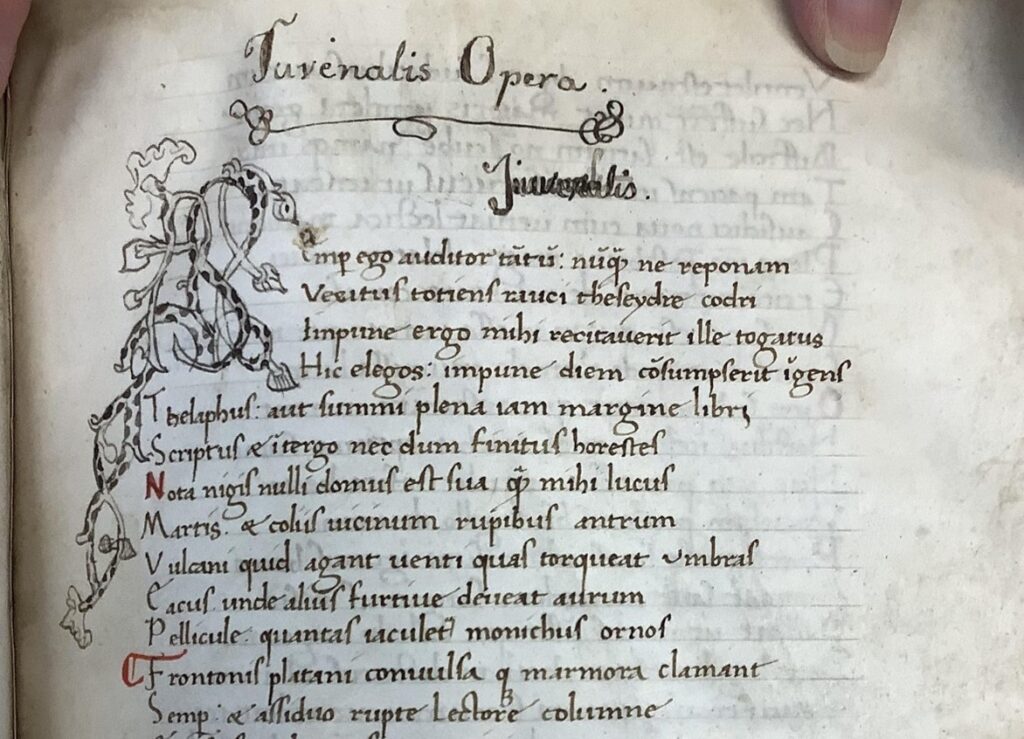

Opening the book, one can see it is written in a humanistic bookhand specifically called Humanistic minuscule on high-quality parchment (Fig. 1). Humanists were interested in revitalizing and harkening back to the classical past they saw in the classical texts they studied, including through their scribal techniques. The classical texts they studied were written in a bookhand called Carolingian minuscule, and Humanistic minuscule was a conscious decision by a group of Italian humanists (starting with Petrarch in the 14th century and perfected by Poggio Bracciolini in the early 15th century) to imitate their classical texts with a more legible (particularly to a modern eye) script. Beyond the bookhand itself, Humanists imitated how Carolingian scribes made their ruling lines. Visible at the end of line 6 in Fig. 1, Humanist ruling lines were done in hardpoint. Hardpoint ruling simply meant that instead of using ink to mark the lines on which to write, a humanist scribe would take a hard point, such as a stylus, to the paper to make the ruling lines without any additional ink.

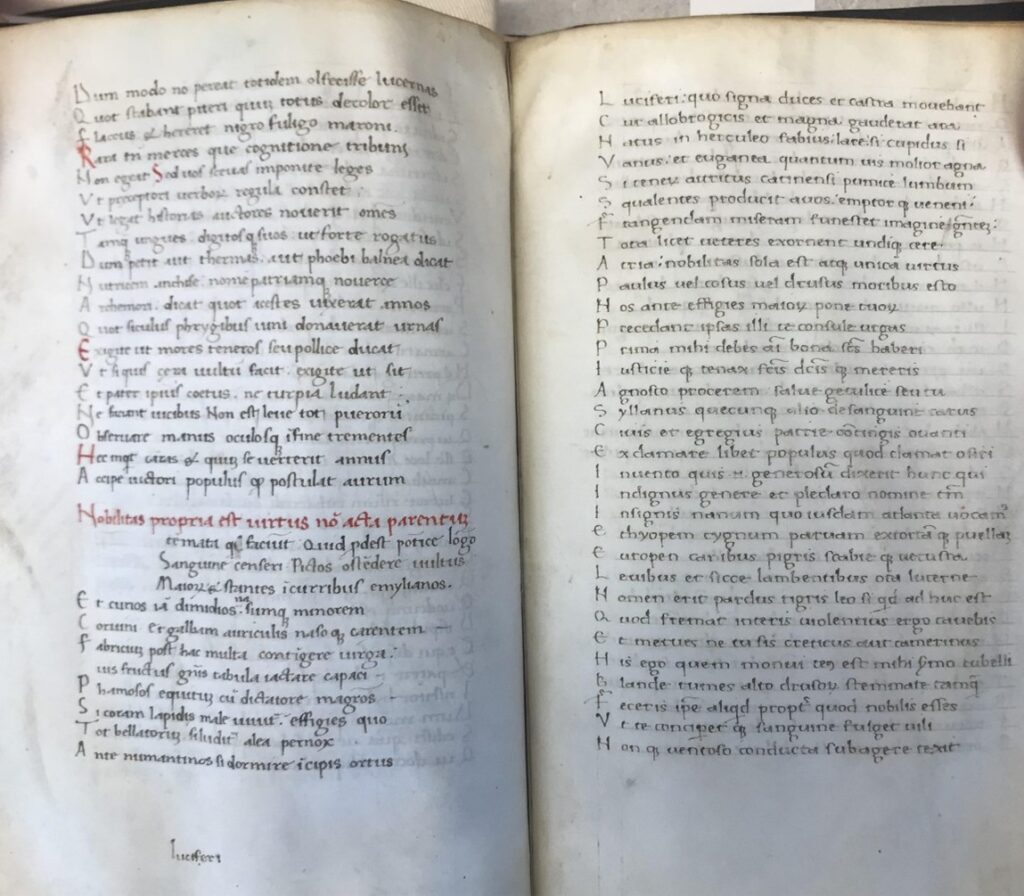

We get to see the handiwork of two different scribes in this book as well, as evidenced in figure 2. The first scribe (let’s call them Scribe A) finished writing on the reverse side of folio 30. On the front side of folio 31, the second scribe (Scribe B) began writing. The quality of the handwriting and decorative work takes, shall we say, a drastic shift once Scribe B takes the mantle. Scribe A did not make their portion of the manuscript particularly ornate, but they did include some instances of red inking for decorative purposes and to write verse introductions to a few of the satires. There is no color to be seen in Scribe B’s portion, though, and their handwriting is notably less neat than Scribe A’s.

TM 942 has some truly entertaining marginalia throughout, but I think my classmates would yell at me if I did not specifically highlight the doodles inside the back cover (Fig. 3). These two puppies were probably drawn by a student who was studying the Satires. I think we can all relate to the experience of distractedly doodling in our textbooks, so these two dogs offer a unique connection across time to a previous user of TM 942. The drawings are silly and a bit dirty – and how wonderful is that? They demystify TM 942, in a way, reminding the present-day reader that, no matter how cool it is and how old it may be, this copy of Juvenal’s Satires is a textbook – an object meant for frequent (and arguably mundane) use.

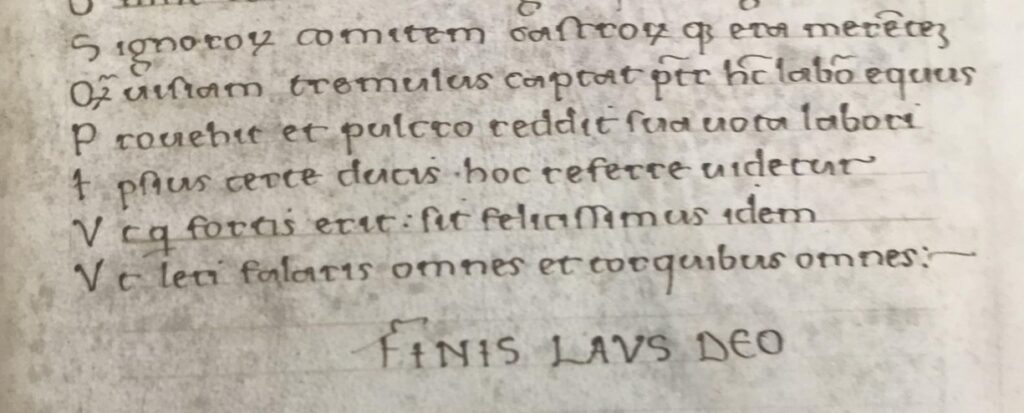

These are only a fraction of the unique and engaging features present in this manuscript copy of Juvenal’s Satires. I will leave you with one of the characteristics that made me giggle the most – even more than the dogs. Scribal work could be a grueling process – it requires constant focus to ensure mistakes are not made, cramped muscles from uncomfortable writing positions, and long bouts of solitude. Scribe B (remember them?) may have been feeling the stress of scribal work particularly heavily on the day they reached the end of folio 61, the very end of the manuscript. After many, many pages of writing, Scribe B wraps up the process in what I see as a hilarious way:

“It is finished – THANK GOD.”

Works Consulted

Hill Museum and Manuscript Library, “Latin Scripts – Humanist.” hmmlschool.org/latin-humanist/.

Les Enluminures, TM 942, Juvenal’s Satires.