The Ovenbird (Seiurus aurocapilla) stands at about 5.5 inches tall and has a wingspan of 10 inches. It ranges from Yukon in northern Canada, through the United States, Mexico and the Caribbean, to Panama, Venezuela and Colombia. And when Winter comes, it migrates through Northeast Georgia. You may recognize its quick “tea-cher” call, but what makes them the most recognizable and from where they draw their name is their nest.

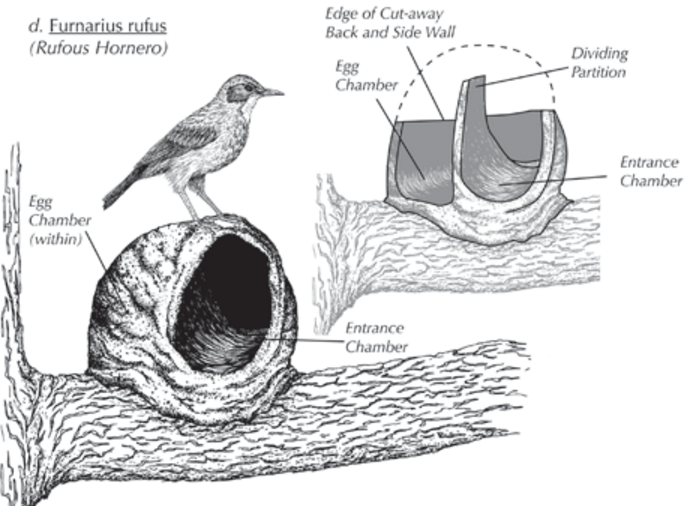

As shown, their nests resemble a traditional dutch oven. They are even sometimes called architects for their elaborately planned nests. To build these requires rain. They must wait for the earth to turn to mud in order to carry the mud to build their nests. This can cause problems in case of a drought. Their alternative choice of course is to build their nests near water. However, they have very strict specifications for nest placement. They prefer to be 60-70 feet from the forest edge over a forest floor with abundant leaf litter. This leaf litter is so vital to them because of their diet. They feed on forest insects and other invertebrates mostly hunted from leaf litter. When Dutch elm disease spread through Minnesota forests, dying trees let more light filter to the forest floor and increased vegetation there; Ovenbird numbers declined.

On top of all these requirements for nesting, they also require more than 250 to 2,000 acres to support an Ovenbird population unless there is a larger patch of forest nearby. They are also quite sensitive to forest fragmentation and to disruption by industrial noise, forest road-building, and logging. Even migration is often dangerous due to the built environment. Large numbers are sometimes killed as they collide with towers and tall buildings along the paths of these fronts.

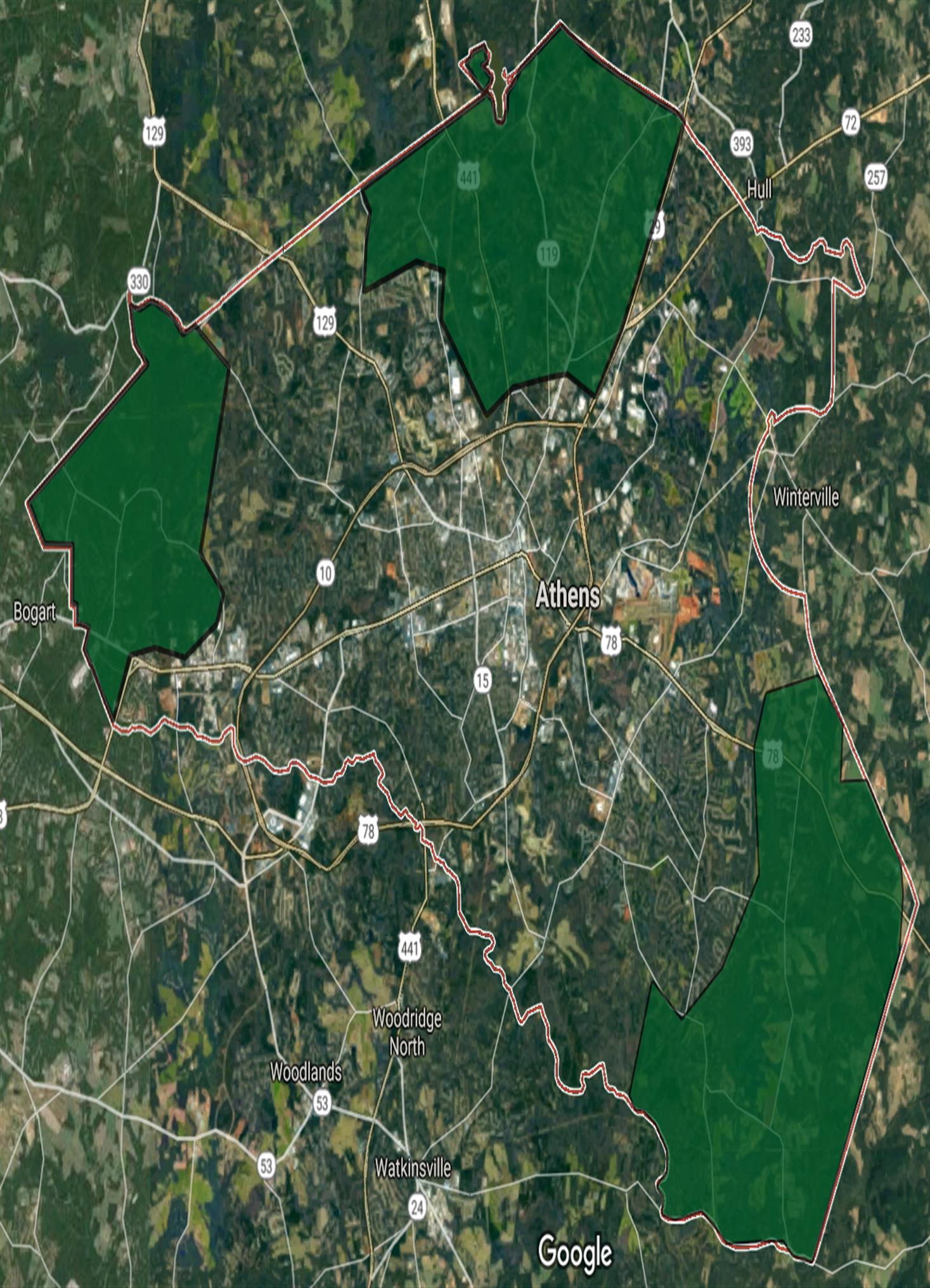

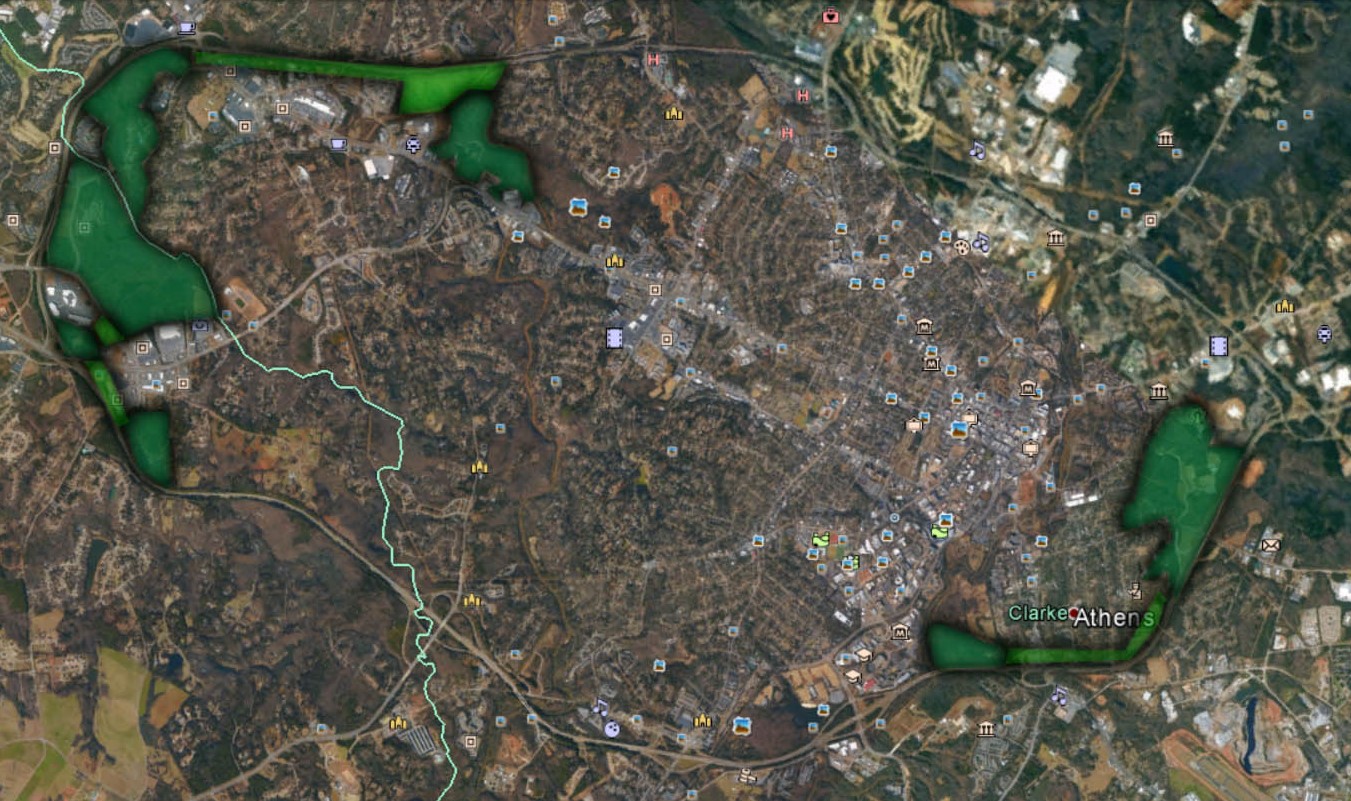

Currently in Athens, there is not much habitat in the city that could properly support a healthy Ovenbird population. All the areas that can support them are at the edges of the city limits. This is due to the rural lands that surround Athens and make better habitat. Within the city, the small patches of thick forests are too spread out to be a conducive environment. This could be resolved by creating corridors between them. In this scenario, tree planting is being prioritized by the location of existing patches of forest and what fills the space between them. If the only consideration was proper habitat for the Ovenbird, trees would be planted densely in any area between the patches that is not already filled with buildings or pavement.

In the map, the dark green shows where patches exist and the light green shows where corridors could be planted. Even a small strip of trees makes a huge difference to wildlife because it connects another patch and double (or even increase much more) the habitat they had prior.

In the previous blog post, land was prioritized for tree planting based on human needs such as population density and trees per capita. Looking at the information on the Ovenbird, other qualities of the landscape would be prioritized primarily the tree stocking level which refers to the amount of trees the land could support. Obviously, the two scenarios differ greatly. In the case of the Ovenbird, our priorities are almost exactly opposite of what they are when we focus solely on the human aspect. For instance, if trees are planted only where there is not currently buildings or pavement, chances are no one lives there, so population density is low.

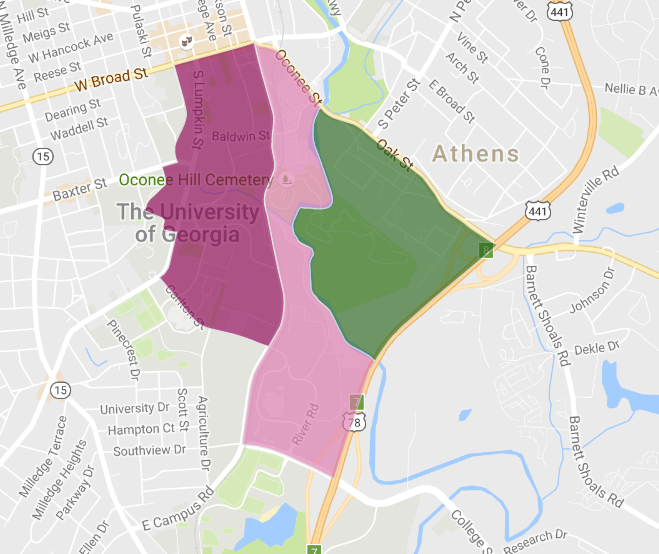

Surprisingly, even with the conflicting goals, when looking at a smaller scale of Athens (near the university) the tree planting priorities set for the goals of increasing the Ovenbird population yield the same results as are human oriented priorities. This is a rare occasion; however, it goes to show that there are scenarios where everyone wins.

When choosing the priorities in tree planting, it is important to think of all aspects of the environment: people, plants, and wildlife. There is a lot to consider, but only this kind of holistic thinking leads to truly successful tree planting plans.