Part I. Community Guide Update and Rationale for Intervention

| Author & Year | Intervention Setting, Description, and Comparison Group(s) | Study Population Description and Sample Size | Effect Measure (Variables) | Results Including Test Statistics and Significance | Follow-up Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Richards, et al., 2013 | The collaborative care intervention took place at 51 primary care facilities located throughout 3 districts in the United Kingdom. This intervention design utilized a cluster randomized controlled trial with adult participants who met ICD-10 criteria for a depressive episode. Participants placed in the intervention group received collaborative care including depression education, drug management, behavioral activation, and communication between a primary care liaison and case manager. Case managers had six to 12 contacts with participants over 14 weeks with a 30-40 minute initial face-to-face appointment, followed by 15 to 20 minute phone contact. Case managers assessed patients at each point using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. The control group of 305 participants received usual care including treatment from their general practitioner and referrals for mental health services. | This study’s sample included 581 adults aged 18 years or older who met ICD-10 criteria for a depressive episode. Participants were recruited from June 2009 until January 2011 from the records of primary care practices located in Bristol, London, and Manchester. | Individual participant depression severity was measured by the patient health questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9) at 4 months. Secondary outcomes were measured at 12 months using the same PHQ-9 scale. A quality of life form (quality of life (short form 36 questionnaire; SF-36) was also taken at baseline, 4 months, and 12 months. Worry and anxiety (generalised anxiety disorder questionnaire; GAD-7) was measured at 4 and 12 months, and patient satisfaction (client satisfaction questionnaire 8; CSQ-8) was measured at 4 months. | The mean depression score at 4 months was 1.33 PHQ-9 points lower (95% confidence interval 0.35 to 2.31, P=0.009) in participants receiving collaborative care than those receiving usual care (control group) after adjustment for baseline depression. Collaborative care produced better outcomes than usual care on the mental component scale of the SF-36 at 4 months, but not 12 months, had little effect on anxiety and the physical component scale of the SF-36. Participants receiving collaborative care were more satisfied with their treatment than those in usual care. | At the 12 month follow-up, the mean depression score was 1.36 PHQ-9 points lower (95% confidence interval 0.07 to 2.64, P=0.04) in participants receiving collaborative care than in those receiving usual care. |

| Pyne, et al., 2011 | The HITIDE intervention was implemented throughout 3 Veterans Affairs HIV Clinics. This intervention included on off-site team consisting of a registered nurse depression care manager, a pharmacist, and a psychiatrist who collectively delivered 12 months of collaborative care to HIV patients experiencing depression. The randomized intervention group received this 12 months of collaborative care and the control group received usual care including primary mental health care. | 249 HIV infected patients with depression completed a baseline interview for this study. Of these 249, 123 were randomized to the intervention and 126 to the control group. In general, the sample primarily consisted of middle-aged, single, African American men, of low to medium economic status. | The primary outcome, depression severity, was measured by the 20 item Hopkins Symptom Checklist (SCL- 20). Additionally, secondary outcomes were measured including self-reported quality of life, HIV symptom severity, and antidepressant or HIV medication regimen adherence. | Participants in the intervention were more likely to report treatment response than those in the control group (33.3% vs 17.5%) (odds ratio, 2.50; 95% confidence interval, 1.37 to 4.56) at 6 months, but not at 12 months. HIV symptom severity at 6 months and 12 months was significantly lowered among the intervention group. No other significant effects were shown among secondary outcomes. | No follow up has been performed past the 12 month period. |

| Lewis, et al., 2017 | The CASPER intervention took place at 32 general practitioners offices located in the Northern England area. Participants in the intervention group (n=344) received this intervention which included low-intensity collaborative care with a case manager delivering behavioral activation over a 7 to 8 week period as well as usual primary care. The control group (n=361) only received usual primary care. | A total of 705 participants, aged 65 years or older with subthreshold depression, or depressive symptoms participated in this study. Of these 705 participants, 586 followed up at 4 months, and 519 participants followed up at 12 months. | The primary outcome utilized was the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9), used to measure depression severity, score at 4 months post baseline. Secondary outcome measures included the use of the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions, Short Form questionnaire-12 items, Patient Health Questionnaire-15 items, Generalized Anxiety Disorder seven-item scale, Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale two-item version, a medication questionnaire and objective data. | At the end of 4 months, the data indicated a favor towards collaborative care that was statistically significant. The average difference on the PHQ-9 scale measuring depressive symptoms was 1.13 points between treatment and control groups (95% confidence interval 0.67 to 1.95 score points; p < 0.001). This indicates that collaborative care was more effective at reducing depressive symptoms than usual care. | After 12 months, the mean difference between the treatment group and control group concerning the PHQ-9 questionnaire was 1.33 score points (95% confidence interval 0.55 to 2.10 score points; p = 0.001). |

In 2010, the Community Preventive Services Task Force recommended implementing collaborative care for the management of depressive disorders based upon strong evidence that this intervention is effective. Following a current systematic review of 32 studies from years 2004-2009 and 37 randomized controlled trial studies, the CPSTF concluded that collaborative care is effective in improving depression symptoms, increasing adherence to treatment, and improving remission and recovery. The CPSTF also concluded that collaborative care provides good economic value based upon studies which assessed costs and benefits.

Upon further review of the literature from 2010 to the present, it is still recommended that collaborative care for the management of depressive disorders is effective based upon strong evidence presented in 3 versatile studies. Each study found that collaborative care was more effective than usual care in reducing depression symptoms and response to treatment. For example, Lewis et al. (2013) found that the average difference in score on the PHQ-9 scale measuring depressive symptoms was 1.13 points higher among the collaborative care intervention group after 4 months (95% confidence interval 0.67 to 1.95 score points; p < 0.001) . Additionally, Richards et al. (2013) received similar results utilizing this measurement with the collaborative care group scoring 1.33 points lower than the control group that received usual care (95% confidence interval 0.35 to 2.31, P=0.009). Lastly, Pyne et al. (2011) reported that HIV positive veterans who received collaborative care treatment throughout this study were more likely to report treatment response than those who received usual care after 6 months. They were also more likely to show decreases in HIV symptom severity at 6 and 12 months. These studies suggest that collaborative care is still more effective with regards to managing depressive disorders than usual care.

Part II. Theoretical Framework/ Model

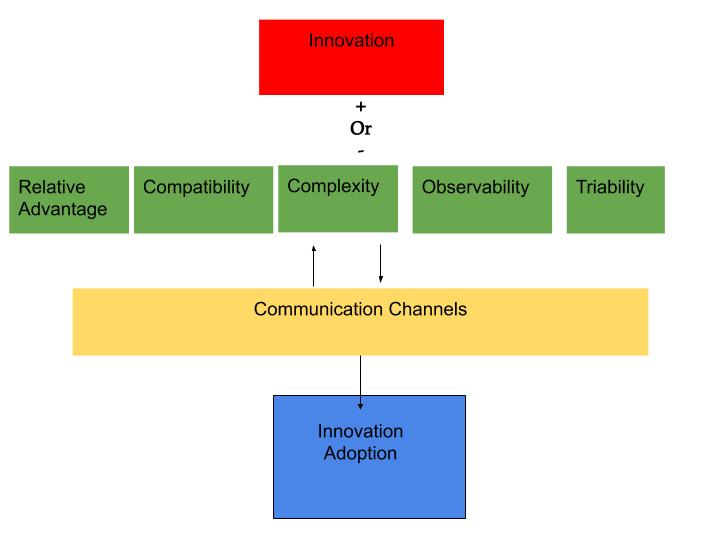

Diffusion of Innovation theory was developed in 1962 to explain how an idea, product, or behavior gains momentum over a period of time and diffuses throughout a population, social system, or society. The adoption of a new idea, product, or behavior means that a specific population is doing something differently than what they have done previously. For this to fully occur, individuals need to view this new concept as something that is innovative (“Behavioral Change Models”, 2018). The following are definitions of concepts that are essential to the understanding of this theory as well as their application to the collaborative care intervention:

1.Innovation: An idea, product, behavior, or practice that is new to an individual, organization, or community; Collaborative care for the management of depressive disorders is not yet widespread so it may be new to various organizations, and it has proven to be effective when compared with usual care.

2.Communication Channels: The ways of transmitting new ideas from one person to another; These communication channels could include the media, but for this intervention, they would include interpersonal communication between different organizations and professionals.

3.Social System: A group of individuals who adopt the innovation. For the collaborative care intervention this may include physicians and primary care practices.

4.Time: How long it takes to adopt the innovation. Time may be dependent upon characteristics of physicians and organizations who wish to adopt the collaborative care intervention.

(Rimer, Glanz, & The National Cancer Institute (U.S.), 2005)

With regards to the collaborative care intervention in this framework, physicians will need to view this intervention as innovative and effective for patients with depressive symptoms in order for the new treatment method to diffuse throughout society and reap benefits for patients. Because this intervention is recommended by the CPSTF and following studies have continued to show the effectiveness of collaborative care for patients experiencing depression, it is believed that the intervention will be viewed as innovative and subsequently have potential for diffusion within an organization or community as long as there are open communication channels. When adopting a new and innovative idea, there are 5 main factors which influence the likelihood that adoption and subsequent diffusion will occur:

- Relative Advantage: The extent to which an innovation is viewed as better than what it is replacing. The collaborative care model has been shown to be more effective than usual care for individuals experiencing depression. For example, Lewis et al. (2013) and Richards et al. (2013) found that individuals who received collaborative care as opposed to usual care scored higher (meaning better) on the PHQ-9 which measures the severity of depression symptoms.

- Compatibility: How consistent the innovation is with the values and needs of its potential adopters. The collaborative care intervention is congruent with the values of physicians and responds to the physician’s need to better treat individuals experiencing depressive symptoms.

- Complexity: How difficult the innovation is or how difficult it is to use. Collaborative care for the management of depressive disorders may seem overwhelming for physicians to implement at first. By hosting the care manager in the same physical setting as the primary care physician within this intervention, collaboration may become easier and complexity should decrease.

- Triability: The extent to which the innovation can be experimented with before full adoption is made. In this intervention, the collaborative care model can be experimented with by physicians, care managers, and mental health professionals participating in order to spur adoption within the practice and community.

- Observability: The extent to which the innovation provides tangible results. The collaborative care innovation has provided tangible and positive results when implemented in the past.

(“Behavioral Change Models”, 2018)

Part III. Logic Model, Causal and Intervention Hypotheses, and Intervention Strategies

My target population is physicians in a primary care practice who provide care for those who are experiencing depressive disorders in the Athens, GA community. Physicians are the target of the intervention in efforts to promote better treatment for individuals experiencing depression within the community. Depression is the number one cause of disability worldwide, and mental disorders are important risk factors for other diseases such as HIV, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes (World Health Organization, n.d.). There is still stigma and discrimination surrounding individuals experiencing a mental illness, and this can lead to exclusion and isolation which further increases symptoms related to mental illness (World Health Organization, n.d.).

| Intervention Method | Alignment with Theory | Intervention Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Increase knowledge among physicians of the benefits of collaborative care for the management of depressive disorders | This intervention aligns with the concepts of relative advantage of the innovation as well as the observability of results. The diffusion of innovation theory states that an innovations relative advantage over other methods as well as the observability of tangible results affect the likelihood that adoption and diffusion will occur. By presenting evidence that collaborative care has been recommended by the CPSTF and subsequent studies, physicians may be more likely to adopt this intervention. | A marketing campaign will be conducted in a primary care practice by public health workers. Public health workers will present the CPSTF’s findings via a one hour educational presentation to physicians on collaborative care for the management of depressive disorders as well as findings from subsequent studies. The public health workers will also display posters throughout the practice setting on the benefits of collaborative care. |

| Introduce a care manager at the primary care practice site | The diffusion of innovation theory states that the complexity of an intervention influences how likely it is that the intervention will be adopted and diffuse throughout a community. The introduction of a care manager in the same setting as the primary care physician will limit complexities related to communication as the physician and care manager will be able to communicate easily in person if they choose. This also increases communication channels which is vital for diffusion to occur. | Public health workers will create an office space for the care manager to work with physicians at the primary care practice setting. The care manager will meet with each of 5 physicians one-on-one each week to discuss patient progress and concerns. The care manager will also contact a patient’s mental health provider each week and relay any concerns to the primary care physician. |

| Introduce physician role model stories | This method aligns with the compatibility and observability concepts within the diffusion of innovation theory. Through physician role model stories, the current physicians will be able to observe how this intervention has provided tangible results in the past which increases the likelihood that this intervention will be adopted. Additionally, the physicians will also observe how this intervention is compatible with practice values such as providing effective evidence-based practices for patients. By displaying compatibility with values, this will further the likelihood that this intervention will be adopted and diffuse. | Physicians who are early adopters of the collaborative care intervention for the management of depressive disorders will share their stories of practice with the 5 participating physicians. Once a week for the 8 week intervention period, the physicians will watch an approximately 30 minute video of the early adopters speaking to their experiences with the implementation process, continued practice, and positive patient experiences and outcomes related to the collaborative care intervention. Physicians will also receive and handout each week summarizing the early adopter’s video presentation. |

| Inputs/Resources | Activities | Outputs | Short-Term Outcomes | Intermediate Outcomes | Long-Term Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| .Funding for two public health workers, a partnership with a primary care practice, research material from the Community Guide and subsequent studies on collaborative care for the management of depressive disorders, funding for one care manager in a primary care practice, a space for one care manager to work in the primary care practice, funding for posters and role model video handout summaries, 8 early adopters/role models of collaborative care, 8 role model videos | One hour presentation on effectiveness of collaborative care for the management of depressive disorders, display of collaborative care posters throughout primary care practice, introduction of space for care manager in primary care setting, care manager meetings with primary care physicians once a week, care manager communication with mental health professionals once a week, 30 minute role model videos each week detailing positive patient experiences and collaborative practice, handouts each week summarizing role model videos | 2 public health workers hired, 1 care manager hired, 1 presentation on the Community Guide findings and subsequent research on collaborative care, increase in knowledge on collaborative care among 5 physicians, 5 posters on collaborative care distributed throughout the practice, 1 role model video each week over an 8 week period, 40 handouts from role models distributed | Physician knowledge of collaborative care for the management of depressive disorders, evidence of a decrease in the complexity of the collaborative care model, evidence of an increase in compatibility of the collaborative care model among physicians | Adoption of collaborative care for the management of depressive disorders in the primary care practice | Diffusion of collaborative care for the management of depressive disorders throughout primary care providers in the community, evidence of a decrease in depressive symptoms among patients in the community |

Intervention Hypotheses

A one hour presentation on the effectiveness of collaborative care for the management of depressive disorders will lead to increases in physician knowledge of collaborative care for the management of depressive disorders.

A display of posters on collaborative care throughout the primary care practice will lead to increases in physician knowledge of collaborative care for the management of depressive disorders.

The introduction of a space for the care manager in the primary care setting will lead to increases in the evidence of a decrease in complexity of the collaborative care model.

The introduction of care manager meetings with the primary care physicians once a week will lead to increases in the evidence of a decrease in complexity of the collaborative care model.

The communication between the care manager and mental health professional once a week will lead to increases in the evidence of a decrease in complexity of the collaborative care model.

Role model videos once a week detailing positive patient experiences and practice experiences will lead an increase in compatibility of the collaborative care model among physicians.

Handouts on role model videos each week will lead to an increase in physician knowledge of collaborative care for the management of depressive disorders.

Causal Hypotheses

Increases in physician knowledge of collaborative care for the management of depressive disorders will increase the adoption of collaborative care throughout primary care physicians in the practice.

Evidence of a decrease in the complexity of the collaborative care model will increase the likelihood of adoption of collaborative care throughout primary care physicians in the practice.

Evidence of an increase in the compatibility of physician values with the collaborative care model will increase the likelihood of adoption of collaborative care throughout primary care physicians in the practice.

SMART Objectives

Objective 1: After participating in the one hour presentation on the effectiveness of collaborative care for the management of depressive disorders, physicians will pass a test with a score of at least 80% detailing components of collaborative care.

Objective 2: When meeting with the care manager at the 1-week mark, each physician will establish and document a scheduled time to meet with the care manager once a week in the office setting to discuss patient progress and concerns, and at the 8-week mark, perceived complexity by physicians will decrease by 80%.

Objective 3: After viewing the role model videos and handouts each week, each physician will discuss and then document one positive effect (for patients) of collaborative care for the management of depressive disorders and how it aligns with physician values, and perceived compatibility of collaborative care will increase by 80% by week 8.

Objective 4: By the 8-week mark, 80% of the physicians will adopt the collaborative care model for the management of depressive disorders.

Part IV. Evaluation Design and Measures

| Stakeholder | Role in Intervention | Evaluation Questions from Stakeholder | Effect on Stakeholder of Successful Program | Effect on Stakeholder of Unsuccessful Program |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physicians/Mental Health Professionals | Intervention participants | How will participation in this program enhance treatment for individuals with depressive disorders? How will my participation in this program help spread this intervention throughout the community? | Increase in knowledge of collaborative care for the treatment of depressive disorders, building of connections with other physicians in the community, reduction in depressive symptoms among patients | No change in knowledge on collaborative care, limited building of connections with other physicians in the community, limited change in depressive symptoms of patients |

| Patients | Receive services from intervention participants | How will participation in this program affect my depressive symptoms? How will participation in this program affect me long term? | A decrease in depressive symptoms, an increase in treatment satisfaction | Limited change in depressive symptoms and treatment satisfaction |

| Funders | Assist with the funding of program | How much will this program cost to implement? Is the program working effectively? Will this program yield results that will be worth the cost? | A desire to continue giving funds for evidence based public health interventions, | A lack of desire to continue funding evidence based public health interventions, wasted time and money |

| Public Health Workers | Implement program | Will the time invested in this program be worth it? How do we make this program work effectively and efficiently? How can we best train physicians and mental health workers in this intervention? | Confidence in the effectiveness and efficiency of this intervention, a desire to continue diffusing this intervention throughout this community and others | Limited confidence in the ability to diffuse the intervention in the future, wasted time and resources |

| Care Managers | Assist with the implementation of the intervention | How can I best help to implement this intervention? Will the time and resources of the program be worth it? | Confidence in the effectiveness of collaborative care for the treatment of depressive disorders, a desire to continue diffusing this intervention | A lack of confidence in the intervention, a lack of confidence in the ability to diffuse the intervention, a waste of resources |

Evaluation Design: Pre-Test Post-Test Non-Randomized Two Group Design

N O X O (Intervention Group)

N O O (Control Group)

Threats to Internal Validity

Two major threats to internal validity in this evaluation design include testing and selection bias.

Testing Bias: Because this evaluation design utilizes pre-tests and post-tests, there will be a threat to internal validity. The use of a pre-test could prime participants into knowledge of the outcomes of the intervention, and this could motivate them to work harder in the office or pay closer attention to patient needs. This indicates that the intervention may not have caused an increase in post-test scores resulting in a decrease in internal validity. Because there is a control group, this lessens the threat of testing bias as both groups will experience the effects of the pre-test but not the intervention.

Selection Bias: Selection bias could be a threat to internal validity because the intervention group and the control group are not a result of random selection and assignment. This is because the intervention takes place within one primary care facility with only 5 physicians. As a result of this small size and single setting, randomization could not occur in the current intervention. If the threat of selection bias were to be lower, a larger sample size and new settings may need to be established for the program to increase internal validity.

| Short-term or Intermediate Outcome Variables | Scales, Questionnaire, Assessment Method | Brief Description of Instrument | Example Item | Reliability Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increase in physician knowledge of collaborative care for the management of depressive disorders | Atkinson, 2007 | 30 true or false questions that relate to the constructs of the diffusion of innovation theory. 6 of the questions measure the relative advantage construct and 6 of the questions measure the observability construct. These constructs are directly related to the likelihood of intervention adoption among physicians. | “Collaborative care is better than usual care for the management of depressive disorders” “I learned about utilizing collaborative care quickly and easily from this intervention” (True/False) | The reliability for the questionnaire was based on Cronbach’s alpha. The relative advantage construct was .9121, simplicity (.8454), triability (.6560), observability (.7581), and translatability (.7428). |

| Evidence of decrease in complexity of the collaborative care model | Atkinson, 2007 | 30 true or false questions that directly relate to the constructs of diffusion of innovation theory. 6 of the questions measure the level of simplicity of the intervention, which is the direct opposite of complexity. A decrease in complexity, or an increase in simplicity, increases the likelihood that the intervention will be adopted. | “I had no difficulty implementing the practice of collaborative care for the management of depressive disorders” (True/False) | The reliability for the questionnaire was based on Cronbach’s alpha. The relative advantage construct was .9121, simplicity (.8454), triability (.6560), observability (.7581), and translatability (.7428). |

| Evidence of an increase in compatibility of the collaborative care model among physicians | Atkinson, 2007 | 30 true or false questions that relate to the constructs of the diffusion of innovation theory. 6 of the questions measure the construct of compatibility within the theory which the presence of is important for adoption and diffusion of interventions. | “I think other primary care physicians should adopt collaborative care in their practice”; “This intervention fit right into my values as a physician” (True/False) | The reliability for the questionnaire was based on Cronbach’s alpha. The relative advantage construct was .9121, simplicity (.8454), triability (.6560), observability (.7581), and translatability (.7428). |

Recruitment and Enrollment

Physician Recruitment Form: Small primary care practices in the Athens, GA area will receive letters via mail from the University of Georgia College of Public Health for recruitment purposes and enrollment in this program. Data will be kept on public health practices that are invited via mail for the intervention, and data will be kept on who returns the enrollment form and who actually takes part in the intervention.

Evidence Based Collaborative Care Intervention Program for the Management of Depressive Disorders

Dear (insert primary care practice here),

The University of Georgia College of Public Health would like to invite your physicians to participate in a study on the practice of collaborative care for the management of depressive disorders. This study is completely voluntary, and there are no known harms to participating in this research. Your participation would include a one-hour educational presentation on the benefits of collaborative care for the management of depressive disorders. Additionally, you would attend weekly meetings with in practice hired care managers and watch and discuss weekly 30-minute educational videos from current collaborative care providers. The benefits of your participation include knowledge and training in the evidence based collaborative care model for the management of depressive disorders. Please send the enrollment form back attached below via fax or email if interested in participating in this study.

Thank you,

Research Enrollment Team

University of Georgia College of Public Health

Enrollment Form for Physicians

Name of Primary Care Practice:

Age Group Treated:

Name of Physicians in Practice:

Date Established:

Address:

Phone Number:

Email:

Days of Meeting Availability:

Signatures ______________ Date: _______________

Recruitment and Enrollment Measures Table

| Primary Care Practice Name: | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physician Name(s): | ||||

| Date of Mailed Recruitment Letter: | ||||

| Date of Enrollment (if applicable): | ||||

| Email: | ||||

| Phone Number: |

Attrition:

The program leaders will have forms to keep track of physician attendance at educational presentations each week and care manager meetings over the course of the 8 week intervention.

Attendance Form:

| Physician Name: | Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5 | Week 6 | Week 7 | Week 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Educational Meeting Attendance (week 1 only): | |||||||||

| Weekly Role Model Video Presentation: | |||||||||

| Weekly care manager meeting: | |||||||||

| Role Model Summary Papers Handed Out: |

Fidelity of the Program:

Each physician will complete the following questionnaire at the conclusion of the intervention to gauge the congruency of the intervention plan and actual result.

| Yes | No | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Did you gain knowledge and understanding from the intial educational presentation on collaborative care effectiveness: | ||||

| Did you observe posters displayed in your practice on collaborative care throughout the intervention? | ||||

| Did you understand the role model story videos that were presented each week? | ||||

| Did you receive handouts each week during the role model video presentation? |

References

Atkinson, N. L. (2007). Developing a questionnaire to measure perceived attributes of eHealth innovations. American Journal of Health Behavior, 31(6), 612-621.

Behavioral Change Models. (2018). Retrieved from http://sphweb.bumc.bu.edu/otlt/MPH-Modules/SB/BehavioralChangeTheories/BehavioralChangeTheories4.html

Lewis, H., Adamson, J., Atherton, K., Bailey, D., Birtwistle, J., Bosanquet, K., … & Gabe, R. (2017). CollAborative care and active surveillance for Screen-Positive EldeRs with subthreshold depression (CASPER): a multicentred randomised controlled trial of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England), 21(8), 1.

Pyne, J. M., Fortney, J. C., Curran, G. M., Tripathi, S., Atkinson, J. H., Kilbourne, A. M., … & Bottonari, K. A. (2011). Effectiveness of collaborative care for depression in human immunodeficiency virus clinics. Archives of Internal Medicine, 171(1), 23-31.

Richards, D. A., Hill, J. J., Gask, L., Lovell, K., Chew-Graham, C., Bower, P., … & Bland, J. M. (2013). Clinical effectiveness of collaborative care for depression in UK primary care (CADET): cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 347, f4913.

Rimer, B. K., Glanz, K., & National Cancer Institute (U.S.). (2005). Theory at a glance: A guide for health promotion practice. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute.

World Health Organization. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.who.int/features/factfiles/mental_health/mental_health_facts/en/index4.html