Part I: Community Guide Update and Rationale for Intervention

Summary of recent interventions using diet physical activity for health behavior change in people with type 2 diabetes.

| Author & Year | Intervention Setting, Description, and Comparison Group(s) | Study Population Description and Sample Size | Effect Measure (variables) | Results, Including Test Statistics and Significance | Follow-up Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ely, E. et al., 2017 | This study examined and evaluated the first 4 years (February 2012 through January 2016) of National Diabetes Prevention Program (National DPP) for type 2 diabetes (T2D) prevention. The National DPP conducts 12 month long interventions in 220 organizations to deliver diabetes prevention programs in 40 states including the District of Columbia. Participants attended a median of 14 sessions over an average of 172 days (median 134 days). | Participants (n=14,747) were ethnically and racially diverse. 44.9% were non-Hispanic white, 10.0% were Hispanic,13.8% were non-Hispanic black, and 31.3% reported another race/ethnicity, or combination or other. | Overall weight loss and amount of time of physical activity PA were measured during the 12 month period. | 35.5% of participants achieved the 5% weight loss goal (with an average weight loss of 4.2%, median 3.1%). Participants reported a weekly average of 152 min of PA (median 128 min), with 41.8% meeting the PA goal of 150 min per week. Each session attended and 30 min of activity reported, participants lost an average of 0.3% of body weight (p<0.0001). | There was a 1 year follow-up time. At this time, 17.5% of participants had lost at least 5% of their body weight which was less than the 35% at the end of the 12 month intervention. |

| Gallé, F. et al., 2019 | This study examined a long term community-based intervention combining aerobic, flexibility, resistance, agility and balance training with motivational interviewing with older adults with type 2 diabetes. Exercise and motivational interventions were carried out in gyms that offered adequate space and trained staff. The control group was 90 type 2 diabetic (T2D) participants (mean age of 64±6.4 years, 58% were male) that only underwent “usual physical activity recommendations.” | Participants (n=69) were T2D (mean age of 63±5.2 years, 62.3% were male) underwent a 9 month exercise program and 12 motivational group meetings focused on physical activity. | Changes in physical fitness were measured by Senior Fitness Tests, Body Mass Index (BMI), HbA1c, waist circumference (WC) and habitual physical activity (PA). PA were expressed in Metabolic Equivalent of Tasks (METs) per min/week. METs were evaluated in each group through the International Physical Activity Questionnaire and compared between groups. | Participants showed significant improvements with a decrease in BMI (29.3 at baseline to 27.6 kg/m2, p <0.03), a decrease in HbA1c (6.5 at baseline to 6.1%, p<0.01), a decrease in WC (104.2 at baseline to 95.6 cm, p <0.01) and improvement in all participant physical fitness parameters (p<0.01) but not in lower body flexibility (p=0.82). Upper body strength (p=0.04) and agility (p ≤0.01) only improved significantly in controls. Habitual PA increased in participants (an increase of 67 min/week) and in controls and (an increase of 19 METs-min/week), p≤0.01. Changes in physical fitness and PA levels registered in the two groups differed significantly (p<0.01). Improvements in BMI, HbA1c and WC did not change significantly (p=0.40, p=0.52, p=0.05 respectively. | There was no follow-up time to date, however a follow-up time was recommended by the authors. |

| Mendes, R. et al., 2016 | This study examined a community-based a supervised exercise program for older adults withT2D. Participants took part in exercise sessions in a community sports complex in Covilhã, Portugal. The complex was equipped with an all-weather running track, outdoor lawns, and an exercise room. The exercise sessions were 70 minutes long and were conducted in three sessions per week. Each session included groups of 30 T2D participants that were supervised by exercise professionals. Sessions took place over 9 months. Measures were assessed at baseline and after the exercise intervention. This study used a non-experimental design, so there were no comparison groups. | Participants were middle-aged and older adults (n=43) with T2D (mean age of 62.92±5.92 years, 48% were male). Participants were randomly selected from a diabetology consultation after applying to participate in a long-term exercise program. Participant inclusion criteria consisted of: must be 55-75 years of age, diagnosed with T2D for a minimum of a year, independent and living in the community, no participation in an exercise program for 6 months and have not smoked in the last 6 months. | The exercise program consisting of participants undergoing PA including aerobic, resistance, agility/balance and flexibility exercises. Aerobic fitness in this study was measured with a 6-Minute Walk Test, muscle strength was measured with a 30-Second Chair Stand Test, agility and balance was measured with a Timed Up and Go Test and flexibility was measured with a Chair Sit and Reach Test. | There were significant improvements in the performance of the 6-Minute Walk Test (an increase of 8.20%, p<0.001), 30-Second Chair Stand Test (an increase of 28.84%, p<0.001), Timed Up and Go Test (an increase of 14.31%, p<0.001), and Chair Sit and Reach Test (an increase of 102.90%, p<0.001). These results represent significant improvements in physical fitness in middle-aged and older adults with T2D. These increases in physical fitness could have substantial benefits in helping the participants with improving their diabetes. | There was no follow-up time to date. |

| Ohlsson, B., 2019 | This study examined the effects of a fiber rich Okinawan-based Nordic based breakfast diet on people with type 2 diabetes. T2D participants ate the Nordic diet for 12 weeks. All participants ate the same diet, except the breakfast in which the treatment group ate the Okinawan-based Nordic based breakfast. This study was conducted at the Skåne University Hospital in Malmö, Sweden. Control group (n=20, 12 were women) consisted of “healthy” participants. Mean age was 46.0±14.5 years. BMI was mean was 24.6±2.7 kg/m2. | Participants with T2D (n=30, 17 were women) were randomly selected from a health center in South Sweden. Mean age was 57.5±8.2 years. BMI was mean was 29.9±4.1 kg/m2. | Biomarkers (e.g., blood glucose levels, blood lipid levels, glucose homeostasis and blood pressure) and physical changes (e.g., BMI and waist circumference) were measured and monitored in both treatment and control groups. | There were significant decreases in BMI (p<0.001), waist circumference (p<0.001), improved glucose homeostasis (p<0.001), decreased diastolic blood pressure (p<0.001), decreased blood glucose levels (p<0.001) and decreased triglycerides (p=0.009). These results were consistent after the 12 week intervention and at follow-up. | Follow-up was 16 weeks after the conclusion of the intervention. |

| Salas-Salvadó, J. et al., 2019 | The PREDIMED-Plus trial is an ongoing 6 year randomized controlled trail (n=6,874) with participants rThe PREDIMED-Plus trial is an ongoing 6 year randomized controlled trail (n=6,874) with participants recruited from 23 Spanish recruitment centers. For the first 12 months, participants were randomized into an intensive weight-loss ] intervention lasting 6 years including an energy-restricted Mediterranean diet (erMedDiet), physical activity and behavioral support. The primary and secondary outcomes were changes in weight and cardiovascular risk markers, respectively. Groups were separated into 2 groups: behavioral support (IG) and a control group (CG). | Participants (n=626) were overweight or obese (≥27 BMI) adults (prediabetic or diabetic). Men were recruited with ages of 55–75 years and women of ages 60-75 years. Participants had no history of cardiovascular disease except for heart failure or valve repair. | Cardiovascular risk factors, waist circumference, fasting glucose, triglycerides and HDL-cholesterol were measured in both IG and CG at baseline and following the first 12 month period of the 6 year study. A 17 item questionnaire was given to access erMedDiet at baseline, at 6 months and at 12 months. | There were significant improvements in diet and PA when comparing the IG to the CG. After 12 months, the IG participants lost an average of 3.2 kg compared to 0.7 kg in the CG (p<0.001), with a mean difference of −2.5 kg (95% CI −3.1 to −1.9). Weight loss of ≥5% was observed with a 33.7% loss in IG participants compared to an 11.9% weight loss in the CG (p<0.001). Cardiovascular risk factors, waist circumference, fasting glucose, triglycerides, and HDL-cholesterol, significantly improved in IG participants (p< 0.002) compared to CG. Decreases in insulin resistance, HbA1c, and circulating levels of leptin, interleukin-18, and MCP-1 were larger in the IG compared to the CG participants (p<0.05). The IG participants with prediabetes/diabetes significantly improved glycemic control and insulin sensitivity, along with triglycerides and HDL-cholesterol levels compared to CG participants. | Follow-up time is 2 years after the 6 year study has ended. |

I was unable to locate follow-up time periods in the Methods Sections for Gallé, F. et al., 2019 or Mendes, R. et al., 2016.

Updated Recommendations

Three out of five studies I found provide support the use of dietary interventions to control type 2 diabetes. In addition, five out of five studies I found provide support for the use of physical activity interventions to control type 2 diabetes. Both types of interventions attempt to control type 2 diabetes through weight loss and the reduction of biological effects of type 2 diabetes. Based on the literature reviewed, there is sufficient evidencethat support interventions using combined dietary and physical activity components for the control of type 2 diabetes.

Based on this research, I strongly recommend an intervention consisting of a 12 month period of 150 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity per week combined with a diet low in carbohydrates, low in saturated fats and high in fiber and protein. Based to the literature reviewed, this type of intervention has statistically significant findings indicating reduced HbA1c, decreased weight loss and increased physical fitness. However, more research is recommended on whether the prescribed diet and physical activity during the intervention are both maintained after follow-up.

Justification

Based on literature reviewed, I have found evidence that physical activity interventions can decrease BMI, decrease waist circumference, reduce HbA1c, decrease blood pressure and induce weight loss. These changes can have beneficial effects on controlling type 2 diabetes. In addition, I have found evidence of interventions consisting of diets that are low in carbohydrates, low in saturated fats and high in fiber and protein can also have beneficial effects on controlling type 2 diabetes. However, I have found evidence that indicates a combination of both diet and physical activity could have more profound benefits and better control over type 2 diabetes.

First, The National Diabetes Prevention Program for type 2 diabetes is currently conducting 12 month long interventions in 220 organizations to deliver diabetes prevention programs in 40 states including the District of Columbia. A descriptive analysis was conducted by Ely et al.on 14,747 participants from the first 4 years of the 6 year program. The National Diabetes Prevention Program has a primary goal of controlling type 2 diabetes by reducing obesity though physical activity. After one 12 month intervention, Elyet al.found that 35.5% of participants achieved the 5% weight loss goal (with an average weight loss of 4.2%, median 3.1%). In addition, participants reported a weekly average of 152 minutes of physical activity (median 128 min), with 41.8% meeting the physical activity goal of 150 min per week. Ely et al.also found that the more physical activity sessions participants were involved in, the more time they would spend per week working towards their goal of 150 minutes of physical activity per week and that each session attended or for every 30 minutes of activity reported, participants lost an average of 0.3% of body weight (p<0.0001). However, at the 1 year follow-up time, Ely et al.found that 17.5% of participants had only lost at least 5% of their body weight which was less than the 35% at the end of the 12 month intervention. These findings indicate evidence of weight loss to control type 2 diabetes, however weight loss alone may not be enough.

Similar to The National Diabetes Prevention Program to reduce obesity by increasing physical activity to control type 2 diabetes, a descriptive study in Portugal assessed a community-based exercise intervention for middle-aged and older adults with type 2 diabetes. Community-dwelling participants took part in the exercise program consisting of aerobics, resistance, agility, balance and flexibility exercises during 70 minute long sessions, three times per week over the course of 9 months. Mendes et al.found significant improvements in aerobic performance (an increase of 8.20%, p<0.001), resistance performance (an increase of 28.84%, p<0.001), agility and balance performance (an increase of 14.31%, p<0.001), and flexibility performance (an increase of 102.90%, p<0.001) which have substantial benefits in helping people control their type 2 diabetes. These findings provide support for increasing physical fitness to control type 2 diabetes and decrease weight loss while improving cardiovascular risk factors, however physical fitness alone may not be enough.

Further and similar to the findings of Ely et al.and Mendes et al.,a randomized control trail in Italy used a physical activity intervention to control type 2 diabetes. Gallé et al. assessed a long term community-based intervention combining aerobic, flexibility, resistance, agility and balance training with motivational interviewing with older adults with type 2 diabetes. Gallé et al. found significant improvements in reduced BMI (29.3 at baseline to 27.6 kg/m2, p <0.03), reduced HbA1c (6.5 at baseline to 6.1%, p<0.01), lowered waist circumference (104.2 at baseline to 95.6 cm, p <0.01), increased levels of habitual physical activity and improvements in all participant physical fitness parameters (p<0.01). Changes in physical fitness and physical activity levels registered in the treatment and control groups differed significantly (p<0.01).Gallé et al. found improvements inBMI, HbA1c and waist circumference inthe treatment group (p=0.40, p=0.52, p=0.05 respectively), however these significant changes were not significant in relation to the control group.

Participants in a treatment group may have not benefitted from physical activity interventions as much because a diet component was not included in the intervention. For example, a study in Sweden examined the effects of a fiber rich Okinawan-based Nordic diet on people with type 2 diabetes. Participants were separated into a treatment group that ate the Nordic diet for 12 weeks and a control group that did not.Both groups ate the exact same foods, except the treatment group ate theOkinawan-based Nordic diet for every breakfast. At the conclusion of the intervention, Ohlsson foundsignificant decreases in BMI (p<0.001), waist circumference (p<0.001), improved glucose homeostasis (p<0.001), decreased diastolic blood pressure (p<0.001), decreased HbA1c(p<0.001) and decreased triglycerides (p=0.009). After the 16 week follow-up, participants maintained these significant findings.

Ohlsson provides evidence that a diet intervention alone can aid in controlling type 2 diabetes, however diet and physical activity may have a greater impact on controlling type 2 diabetes. For example, a randomized control trail in Spain assessed the effectiveness of an intervention combining a Mediterranean diet and physical activity. Participants were randomly separated into an intervention group and a control group. Cardiovascular risk factors, waist circumference, fasting glucose, triglycerides and HDL-cholesterol were measured in both treatment group and control group at baseline, at 6 months and at 12 months. Salas-Salvadó et al. found significant improvements in diet and physical activity when comparing the treatment group to the control group. After 12 months, the treatment group lost an average of 3.2 kg compared to 0.7 kg in the control group (p<0.001), with a mean difference of −2.5 kg (95% CI −3.1 to −1.9). Weight loss of ≥5% was observed at 33.7% in treatment group compared to an 11.9% in the control group (p<0.001). In addition, the treatment group had larger decreases in insulin resistance, HbA1cand circulating levels of leptin than the control group (p<0.05). Therefore, participants with prediabetes or diabetes significantly improved glycemic control and insulin sensitivity, along with triglycerides and HDL-cholesterol levels.

There are no changes to my recommendation. Based on the literature reviewed, I strongly recommend using an intervention that combines both diet and physical activity to control type 2 diabetes. The intervention should last for 12 months and a goal of 150 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity should take place. While intervening with physical activities, a diet that is low in carbohydrates, low in saturated fats, and high in fiber and protein (e.g., the Mediterranean or Okinawan-based Nordic diet diets). Further research should be done to better understand the maintenance of the diet and physical activity after the conclusion of the intervention. People with type 2 diabetes may have successful results during the yearlong intervention, but the lifestyle change must be long term to gain the most beneficial effects.

Part II: Theoretical Framework and Model

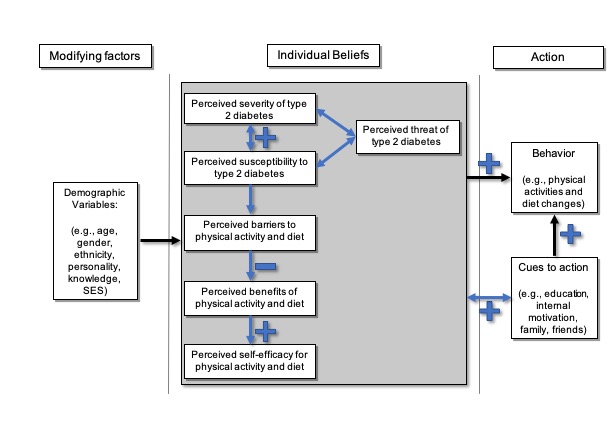

Heath Belief Model (HBM)

The Health Belief Model is an individual-level behavior change theory that is useful for constructing health behavior change interventions. The constructs on the HBM are 1) perceived susceptibility, 2) perceived severity, 3) perceived benefits, 4) perceived barriers, 5) cues to action and 6) self-efficacy. Because of these constructs, the HBM is a well suited theory for changing the behaviors (e.g., increasing physical activity and promoting diet) of people with type 2 diabetes. I chose the HBM as a theory for promoting physical activity and diet change for people at risk or living with type 2 diabetes because the constructs educate people about disease, help alleviate misconceptions about disease, help create a plan for behavior change and the benefits of the behavior change, help create action for change and create self-efficacy to maintain the health behavior change.

1) Perceived Susceptibility: is a construct of the HBM that describes a person’s beliefs about the chances of getting a disease or condition. For example, perceived susceptibility is someone’s belief that they might or might not be diagnosed with type 2 diabetes if they do not exercise regularly or eat a nutritious and balanced diet.

Strategies to promote perceived susceptibility are defining the population that is at risk and their degrees of risk, adapting risk information based on an individual’s demographic variables, characteristics or behaviors and helping individuals develop a precise perception of their risk.

- For example, educating someone on how likely someone is to becoming type 2 diabetic or living with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes can help promote health behavior change.

2) Perceived Severity: is a construct of the HBM that describes a person’s beliefs about the seriousness of a disease and the consequences of that disease. For example, perceived severity is someone’s belief that being diagnosed with type 2 diabetes will be negative and cause serious health issues and could even lead to death.

Strategies to promote perceived severity include are identifying and detailing the consequences of a disease and recommending action. In addition, emotions (e.g., distress and regret) can be triggered with images to change an individual’s beliefs.

- For example, educating how serious type 2 diabetes is and the other health risks people have when they live with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes can help promote health behavior change.

3) Perceived Benefits: is a construct of the HBM that describes a person’s beliefs about the effectiveness of taking action to reduce risk or seriousness. For example, does someone perceive an intervention or program consisting of physical activity and diet change benefit them as a person living with type 2 diabetes? Or does someone believe physical activity and diet change can reduce the chance of living with type 2 diabetes?

Strategies to increase perceived benefits are explaining how to take action, where to take action and when to take action. In addition, describing the potential positive results is another strategy to increase perceived benefits and shift the individual’s perspective by highlighting others’ beliefs about the behavior and its effects.

- For example, explaining how to change someone’s physical activity and diet behaviors and how exercising and eating well can decrease the risk of type 2 diabetes which will reduce other comorbidities.

4) Perceived Barriers: is a construct of the HBM that describes a person’s beliefs about the tangible, intangible or psychological costs of taking action. For example, does someone view physical activity and changing their diet as monetarily expensive, requiring extra time and energy they do not have or does the program cause added stress?

Strategies to reduce perceived barriers are offering reassurance, incentives, assistance and correcting misinformation.

- For example, alleviating the idea of physical barriers and offering reassurance that physical activity and diet change can be difficult, but health is very important can help the success of someone during health behavior change interventions.

5) Cues to Action: is a construct of the HBM that describes a person’s influences that initiate willingness to change. For example, does a person with type 2 diabetes want to control their diabetes because they have children for whom they want to be healthy and watch them grow up? Or does a person with type 2 diabetes not want their health to be a burden on their family and friends?

Strategies to create cues to action are providing ”how to” information, promoting awareness and constructing reminders and recall mechanisms.

- For example, helping someone plan physical activities and a meal plan can help promote health behavior change.

6) Self-Efficacy: is a construct of the HBM that describes a person’s self-confidence in their ability to take control over their actions and life. For example, does a person with type 2 diabetes want to take control of their health and increase their physical activity and change their diet to become healthier?

Strategies to create self-efficacy are providing adequate training and guidance to perform an action, using goal setting, giving verbal reinforcement, demonstrating desired behaviors, and reducing anxiety about taking action.

- For example, Gallé et al. incorporated motivational interviewing into a physical activity intervention for middle-aged and older adults with type 2 diabetes. Gallé etal. found significant improvements in reduced BMI, reduced HbA1c, lowered waist circumference and increased levels of habitual physical activity. By incorporating motivational interviewing, an intervention can increase self-efficacy and improve internal motivation to succeed in a behavioral change such as physical activity and diet change.

Components and Constructs of the Health Belief Model

Part III: Logic Model, Causal and Intervention Hypotheses, and Intervention Strategies

Target Population

The target population of this intervention is community-dwelling children, adolescents, adults and older adults living with or at risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report that some minority racial and ethnic groups of people are disproportionally affected by type 2 diabetes and are therefore at greater risk of developing type 2 diabetes (2017). Higher prevalence of type 2 diabetes in American Indians, Alaska Natives, Hispanic and Black (non-Hispanic) people can be related to genetics, obesity, food insecurity, low access to healthcare, stress, racism, cumulative disadvantage and low socioeconomic status (Bhupathiraju et al., 2016).

The intervention setting is within the community at local schools facilities (e.g., fields, tracks, swimming pools, tennis courts, basketball courts, baseball fields, gyms, etc.); local hospitals, clinics, fire stations and the local health department. Recruitment will largely be from referrals from local hospitals, physician’s offices, health departments local schools and word of mouth.

The intervention methods for the program

| Intervention Method | Alignment With Theory | Intervention Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Persuasive Communication and Consciousness Raising: Increase awareness and knowledge about perceived severity, perceived susceptibility and perceived threat of type 2 diabetes. | The Health Belief Model constructs of perceived severity, perceived susceptibility and perceived threat are core concepts of this intervention. Increasing awareness about type 2 diabetes by promoting education and knowledge about perceived susceptibility to type 2 diabetes, perceived severity of type 2 diabetes and the perceived threat of type 2 diabetes promotes knowledge about negative outcomes that could be avoided with behavior change. This will may lead to perceived benefits of physical activity and diet and cues to action. | Health Communication: Use one-on-one counseling for health and mental health education and awareness. Health Communication and Health Education: Use community-based peer (e.g., health outreach workers) group meetings for brainstorming, increasing awareness, discussion and education within the community at schools, firehouses, hospitals, nursing homes and other public spaces (e.g., health fairs). Health Communication: Describe and educate about the negative health outcomes of type 2 diabetes and the comorbidities that are related to type 2 diabetes with informative and cultural relevant talks/lectures, videos, handouts and cell phone applications. Create culturally relevant lectures, videos and handouts consisting of information about the biological foundations of type 2 diabetes, the biological effects of the disease, the severity of type 2 diabetes and how susceptible people are to developing type 2 diabetes. |

| Consciousness Raising: Increase knowledge and awareness about reducing perceived barriers to physical activity and eating a healthy diet. | The Health Belief Model construct of perceived barriers is core concepts of this intervention. Reducing perceived barriers to physical activity and diet change can promote behavior change, increase perceived benefits and create cues to action. | Health Communication: Use one-on-one counseling for health and mental health education and awareness. Educate and describe ways to reduce barriers to physical activity and diet change. Health Communication: Use community-based peer (e.g., health outreach workers) group meetings for brainstorming, increasing awareness, discussion and education within the community at schools, firehouses, hospitals, nursing homes and other public spaces (e.g., health fairs). Health Education: Provide culturally relevant training and guidance on how to decrease or remove perceived barriers to behavior change. |

| Persuasive Communication and Consciousness Raising: Raise awareness and increase knowledge about the benefits of physical activity and diet. | The Health Belief Model construct of perceived benefits is core concept of this intervention. Raising awareness and increasing knowledge about the benefits of beginning or increasing physical activities and the benefits of beginning or increasing a healthy and well balanced diet to promote positive motivations for behavior change. This could promote moving into self-efficacy and provide cues to action. | Health Communication: Use one-on-one counseling for health and mental health education and awareness. Health Communication: Community-based peer (e.g., health outreach workers) group meetings for brainstorming, discussion and education to raise awareness of perceived benefits of beginning or increasing physical activities and eating a healthy well-balance diet within the community at schools, firehouses, hospitals, nursing homes and other public spaces (e.g., health fairs). Health Communication: Demonstrate ways to be physically active with informative and culturally relevant talks/lectures, videos, handouts cell phone applications and websites. Health Communication: Demonstrate ways to plan and eat a heathy diet with informative and culturally relevant talks/lectures, videos and handouts. Demonstrate ways to create a physical activity and diet diary to keep track of daily, weekly and monthly goals to increase motivation. Health Education: Increase awareness by using community role models on how to safely perform physical activities and how to create a plan for physical activity and eating a healthy diet. |

| Autonomy Building: Promote self-efficacy, autonomy and develop skills to increase the desire to be physically active and eat a well-balanced nutritious diet. Use motivational interviewing to build autonomy. Role Models and Guided Practice: Use community role models living with type 2 diabetes to show how to be or become physically active and how/what to eat. Create a plan for physical activity and how to eat a healthy diet. | The Health Belief Model construct of perceived self-efficacy is core concept of this intervention. Increasing perceived self-efficacy for physical activity and diet change may promote maintenance of behavior change and increase cues to action. | Health Communication: Use one-on-one counseling, motivational interviewing and education to promote self-efficacy and behavior reinforcement for health behavior change. Use one-on-one counseling for health and mental health education and awareness. Health Communication: Community-based peer (e.g., health outreach workers) group meetings for brainstorming, increasing awareness, discussion and education to promote self-efficacy and behavior reinforcement for health behavior change within the community at schools, firehouses, hospitals, nursing homes and other public spaces (e.g., health fairs). Health Education: Provide culturally relevant training and guidance by using community role models living with type 2 diabetes on how to safely perform and create a plan for physical activity and how to eat a healthy diet. |

| Persuasive Communication, and Consciousness Raising: Promote awareness and cues to motivation to increase desire to be physically active and eat a well-balanced nutritious diet. Role Models: Use community role models living with type 2 diabetes to show how to be or become physically active and how/what to eat in increase cues to action. | The Health Belief Model construct of cues to action is core concepts of this intervention. Promoting cues to action can increase behavior change through understanding perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived threat, perceived barriers, perceived benefits and self-efficacy. | Health Communication: Promote awareness and provide cues and motivation to action with culturally relevant talks/lectures, videos and handouts within the community at schools, firehouses, hospitals, nursing homes and other public spaces (e.g., health fairs) Health Communication: Promote awareness and provide cues to action and motivation with community role models living with type 2 diabetes. Health Education: Provide and create culturally relevant pamphlets, workbooks, films and pictures to increase awareness and knowledge of type 2 diabetes and how to better use self-care, medications and doctor’s visits to maintain good health and control type 2 diabetes. |

Logic Model for the Program

| Inputs/ Resources | Activities | Outputs | Short-term Outcomes (3 months) | Intermediate Outcomes (6 months) | Long-term Outcomes (12 months and beyond) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technical Equipment/Supplies: Allocate funding for educational materials (e.g., computer equipment for power point slides, projector for lecture/talks, pamphlets/handouts, videos). Support: Allocate time for educational lectures/talks, one-on-one counseling, group sessions, field trips and health fairs. | Provide culturally relevant and age appropriate educational lectures/talks, handouts and videos for to community-dwelling children/adolescents, adults and older adults for 60 minutes for 2 sessions a week at local school facilities consisting of diabetes, physical activities and nutrition course of the yearlong intervention. | 5,000 culturally relevant and age appropriate pamphlets/handouts provided during educational lectures/talks and health fairs. 100 culturally relevant and age appropriate educational lectures/talks provided (approximately 2 per week). Community-dwelling children/adolescents, adults and older adults taught about type 2 diabetes and how to prevent and control type 2 diabetes. | Increase knowledge and awareness about type 2 diabetes. Increase perceived benefits of physical activity and diet. Generate self-efficacy for physical activity and healthy eating. | Increased physical activity with participants striving towards the goal of 150 minutes of moderate-vigorous exercise per week. Increased consumption of healthy foods (nutritious diet) that are low in sodium, low in saturated fat low in carbohydrates, and high in fiber and protein. Decreasing participant obesity, BMI, blood glucose levels and A1c in participants from baseline screening. | Increased knowledge about negative effects of type 2 diabetes and how to control blood glucose levels and A1c and type 2 diabetes. Decrease in the prevalence of type 2 diabetes and the comorbidities of type 2 diabetes of all ages. Decrease in the incidence of type 2 diabetes. Decrease of type 2 diabetes in high risk individuals. Decreased obesity, BMI, blood glucose levels and A1c in participants from baseline screening. |

| Personnel: Allocate funding for staff to conduct one-on-one counseling sessions. Personnel: Allocate funding for staff to conduct group sessions. Facilities: Form partnerships with local schools (e.g., elementary schools, middle schools and high schools) to conduct educational sessions at their facilities. Technical Equipment: Funding for screening equipment including scales to measure weight, calipers to measure BMI and multi-test glucometers for blood glucose monitoring and A1c monitoring. | Provide one-on-one counseling lasting 60 minutes to community-dwelling children/adolescents, adults and older adults for 2 sessions a week at local school facilities course of the yearlong intervention. Provide culturally relevant and age appropriate group (e.g., town hall) sessions for adults and older adults promoting discussion, brainstorming, increasing awareness and promoting education lasting 60 minutes for 2 sessions a week at local school facilities course of the yearlong intervention. Conduct weekly educational sessions for community-dwelling children/adolescents, adults and older adults that are 60 minutes long for 2 sessions a week at local school facilities. Sessions will describe type 2 diabetes, the biological foundations of type 2 diabetes, the negative health outcomes of type 2 diabetes, the comorbidities of type 2 diabetes, the benefits of eating a healthy diet (e.g., low in sodium, low in saturated fat and low in carbohydrates) and the negative outcomes of eating a poor diet. Sessions will also teach participants how to create a physical activity and food journal course of the yearlong intervention. Screening of baseline BMI, blood glucose levels and A1c of community-dwelling children/adolescents, adults and older adults. | 100 one-on-one counseling sessions provided over the course of the yearlong intervention (approximately 2 per week). 100 educational group sessions provided (approximately 2 per week). 10 staff members trained to conduct one-on-one counseling. 5 staff members trained to conduct group sessions. These 5 staff members are also trained to use screening instruments including scales to measure weight, calipers to measure BMI and multi-test glucometers for blood glucose monitoring and A1c monitoring. Local school teachers and school staff trained to assist intervention staff with one-on-one counseling sessions, group sessions and screening instruments. Community-dwelling children/adolescents, adults and older adults taught about type 2 diabetes and the negative health outcomes of type 2 diabetes. | Increase awareness and knowledge about and type 2 diabetes. Increase perceived benefits of physical activity and diet. Generate self-efficacy for physical activity and healthy eating. | ||

| Personnel: Allocate funding for staff to conduct physical activity training, exercise sessions and diet training at local school facilities. Personnel: Recruit volunteers to assist staff in activity training, exercise sessions and diet training at local school facilities. Personnel: Recruit volunteers as community role models currently living or have lived with type 2 diabetes, controlling and working to decrease risk of type 2 diabetes. | Provide 6 educational sessions for community-dwelling children/adolescents, adults and older adults at the beginning of the intervention hosted by staff and volunteers to train participants how to exercise safely and effectively to promote physical activity for 150 minutes per week in local school facilities course of the yearlong intervention. Provide 6 educational sessions for community-dwelling children/adolescents, adults and older adults at the beginning of the intervention hosted by staff and role models train participants how to exercise safely and effectively to promote physical activity for 150 minutes per week in their homes, parks and local schools course of the yearlong intervention. Provide 3 weekly exercise sessions for community-dwelling children/adolescents, adults and older adults lasting 60 minutes at local school facilities (approximately 150 per year) over the course of the yearlong intervention. | 5 additional staff trained to conduct informational sessions provided at local school facilities about how to be physically active, become physically active and continue to be physically active. Staff also trained to conduct informational sessions about how eat a healthy diet. Staff also trained to provide 3 weekly exercise sessions lasting 60 minutes. 10 additional volunteers trained to help conduct informational at local school facilities sessions about how to be moderately-vigorously physically active, become physically active and continue to be physically active. Volunteers also trained to conduct informational sessions about how eat a healthy diet. Community-dwelling children/adolescents, adults and older adults taught about type 2 diabetes and physical activity and eating a healthy diet. | Decrease perceived barriers to physical activity and healthy eating. Increase perceived benefits of physical activity and healthy eating. Generate cues to action, increase motivation, autonomy and self-efficacy. | ||

| Transportation: Allocate funding for transportation for field trips. Facilities: Form partnerships with local hospitals and clinics. Facilities: Form partnerships with local fire departments. | Provide 1 weekly field trip for community-dwelling children/adolescents, adults and older adults to a local hospital, clinics or fire station to promote access to health care and decrease perceived barriers to health care. Host 1 monthly health fairs for community-dwelling children/adolescents, adults and older adults at a local hospital, clinic or fire station to hold educational sessions and perform health screenings (e.g., check blood glucose levels, A1c, blood pressure and weight) over the course of the yearlong intervention. | 100 health care employees at local hospitals and local clinics and 25 fire fighters/paramedics trained to participate in health fairs. Community-dwelling children/adolescents, adults and older adults screened for type 2 diabetes. | Decrease perceived barriers to local access of health care facilities. Increase perceived benefits of health care services. Generate self-efficacy for physical activity and healthy eating. | ||

| Facilities: Form partnerships with local gyms to promote increased availability and accessibility of exercise spaces. | Provide 2 field trips for community-dwelling children/adolescents, adults and older adults to local gyms at the beginning of the intervention to increase awareness of availability and accessibility to exercise spaces and to decrease perceived barriers to physical activity. | Employees of 2 local gyms are trained to provide information about availability and accessibility to exercise at gyms. Community-dwelling children/adolescents, adults and older adults taught about availability and accessibility to exercise spaces. | Decrease perceived barriers to physical activity and healthy eating. | ||

| Facilities: Form partnerships with local farmer’s markets. Transportation: Allocate funding for transportation for field trips. | Provide 4 field trips for community-dwelling children/adolescents, adults and older adults at the beginning of the intervention to local farmer’s markets to educate participants on how to select produce, the benefits of eating whole fruits and vegetables, the benefits of eating a low sodium, low saturated fat, low carbohydrate, high fiber and high protein diet. | 10 local farmers trained to provide information about how to shop at a farmer’s market and how to pick out good fruits and vegetables. Community-dwelling children/adolescents, adults and older adults taught about selecting whole foods at local farmer’s markets. | Generate self-efficacy for healthy eating. Increase perceived benefits of eating a healthy diet. Generate cues to action, increase autonomy and motivation. | ||

| Facilities: Form partnerships with local restaurants. | Conduct weekly educational sessions for community-dwelling children/adolescents, adults and older adults for 60 minutes long 1 time per week about preparing and cooking nutritious meals at local school facilities over the course of the yearlong intervention. | Employees of 5 local restaurants trained to provide informational sessions about how to prepare and cooking nutritious meals. 50 educational sessions provided for 60 minutes long about preparing and cooking nutritious meals. Community-dwelling children/adolescents, adults and older adults taught about healthy meal preparation and cooking. | Develop skills and self-efficacy for preparing and cooking nutritious meals. Generate self-efficacy for healthy eating. |

“Health Communication and Education” subtitle removed from “Short-term Outcomes” in Logic Model.

Adjusted Logic Model to only reflect SMART Objects and included measures.

Intervention Hypotheses:

Attending educational lectures and talks, watching educational videos and receiving informational handouts about the biological foundations of type 2 diabetes and the negative health outcomes of type 2 diabetes will increase participants’ knowledge about type 2 diabetes, increase self-efficacy and perceived benefits while reducing perceived barriers to physical activity and eating a healthy diet.

Attending one-on-one counseling sessions and group sessions about the promotion of good health, improved mental health and the benefits of physical activity and diet will increase participants’ knowledge about type 2 diabetes, increase self-efficacy and perceived benefits while reducing perceived barriers to physical activity and eating a healthy diet.

Attending educational sessions, watching educational videos and receiving informational handouts demonstrating what physical activity is and how to become physically active, will increase participants’ self-efficacy and perceived benefits while reducing perceived barriers to physical activity.

Attending educational sessions, watching educational videos and receiving informational handouts demonstrating what a healthy diet is and how to eat a healthy diet, will increase participants’ self-efficacy and perceived benefits while reducing perceived barriers to eating healthy diet.

Attending field trips to local farmer’s markets will increase participants’ self-efficacy and perceived benefits while reducing perceived barriers to eating healthy diet.

Attending field trips to local restaurants to demonstrate how to prepare and cook healthy foods will increase participants’ self-efficacy and perceived benefits while reducing perceived barriers to eating healthy diet.

Causal Hypotheses:

- Increased knowledge of the biological foundations of type 2 diabetes and how to prevent and control type 2 diabetes will increase cues to action in participants to control blood glucose levels and A1cand type 2 diabetes. This will decrease the incidence and prevalence of type 2 diabetes in the community where the intervention takes place.

- Increased knowledge about the benefits of 150 minutes of moderate-vigorous physical activity per week will decrease the risk of participants developing type 2 diabetes and decrease the risk of developing comorbidities of type 2 diabetes. This will decrease the incidence and prevalence of type 2 diabetes in the community where the intervention takes place.

- Increased knowledge about eating a healthy diet that is low in sodium, low in carbohydrates, low in saturated fat, and high in fiber and protein will decrease the risk of developing type 2 diabetes which will decrease the incidence and prevalence of type 2 diabetes in the community where the intervention takes place.

- Increased knowledge and awareness of perceived barriers to physical activity and eating a healthy diet will decrease the risk of participants developing type 2 diabetes which will decrease the incidence and prevalence of type 2 diabetes in the community where the intervention takes place.

- Increased knowledge and awareness about the benefits of eating a healthy diet will decrease the risk of participants developing type 2 diabetes which will decrease the incidence and prevalence of type 2 diabetes in the community where the intervention takes place.

- Increased self-efficacy for physical activity and eating a healthy diet will decrease the risk of developing type 2 diabetes which will decrease the incidence and prevalence of type 2 diabetes in the community where the intervention takes place.

SMART Outcome Objectives for the Program:

Goal 1: Increase knowledge of type 2 diabetes in in participating community-dwelling children, adolescents, adults and older adults at risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

Objective 1: 3 months after the intervention, 10% of participants will increase their knowledge of type 2 diabetes score by 25%.

Objective 2: 6 months after the intervention, 25% of participants will increase their knowledge of type 2 diabetes score by 50%.

Objective 3: 12 months after the intervention, 50% of participants will increase their knowledge of type 2 diabetes by score 75%.

Goal 2: Reduce perceived barriers of physical activity and eating a healthy diet in participating community-dwelling children, adolescents, adults and older adults at risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

Objective 1: 3 months after the intervention, 10% of participants will decrease their perceived barriers to physical activity and eating a healthy diet score by 25%.

Objective 2: 6 months after the intervention, 25% of participants will decrease their perceived barriers to physical activity and eating a healthy diet score by 50%.

Objective 3: 12 months after the intervention, 50% of participants will decrease their perceived barriers to physical activity and eating a healthy diet score by 75%.

Goal 3: Increase awareness of benefits from physical activity and eating a healthy diet in participating community-dwelling children, adolescents, adults and older adults at risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

Objective 1: 3 months after the intervention, 10% of participants will increase benefits from physical activity and eating a healthy diet score by 25%.

Objective 2: 6 months after the intervention, 25% of participants will increase benefits from physical activity and eating a healthy diet score by 50%.

Objective 3: 12 months after the intervention, 50% of participants will increase benefits from physical activity and eating a healthy diet score by 75%.

Goal 4: Promote self-efficacy to be physically active and eat a healthy diet in participating community-dwelling children, adolescents, adults and older adults at risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

Objective 1: 3 months after the intervention, 10% of participants will increase self-efficacy to be physically active and eat a healthy diet score by 25%.

Objective 2: 6 months after the intervention, 25% of participants will increase self-efficacy to be physically active and eat a healthy diet score by 50%.

Objective 3: 12 months after the intervention, 50% of participants will increase self-efficacy to be physically active and eat a healthy diet score by 75%.

Goal 5: Increase participants’ physically activity in participating community-dwelling children, adolescents, adults and older adults at risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

Objective 1: 3 months after the intervention, 10% of participants will increase physically activity score by 25%.

Objective 2: 6 months after the intervention, 25% of participants will increase physically activity score by 50%.

Objective 3: 12 months after the intervention, 50% of participants will increase physically activity score by 75%.

Goal 6: Increase participants’ eating a healthy diet in participating community-dwelling children, adolescents, adults and older adults at risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

Objective 1: 3 months after the intervention, 10% of participants will increase eating a healthy diet score by 25%.

Objective 2: 6 months after the intervention, 25% of participants will increase eating a healthy diet score by 50%.

Objective 3: 12 months after the intervention, 50% of participants will increase eating a healthy diet score by 75%.

Part IV: Evaluation Design and Measure

Major Stakeholders

| Stakeholder(s) | Role in Intervention | Evaluation Questions from Stakeholder | Effect on Stakeholder of a Successful Program | Effect on Stakeholder of an Unsuccessful Program |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community-dwelling children, adolescents, adults and older adults living with or at risk of developing type 2 diabetes. | Program participants served by the program. | What will I achieve or gain from participation in the program? How will participation in the program prevent me from developing type 2 diabetes? How will participation in the program help me control type 2 diabetes? How much time will we need to invest in the program? What are the negative consequences for me if I do not participate in the program? Will this program cost me any money? Is the program helpful or harmful to me? | Decreased incidence and prevalence of type 2 diabetes in community-dwelling children, adolescents, adults and older adults. Decreased BMI, blood glucose levels and A1c in community-dwelling children, adolescents, adults and older adults living with or at risk of developing type 2 diabetes.. Increased perceived susceptibility, perceived severity and perceived threat of type 2 diabetes. Increased knowledge and awareness of type 2 diabetes, the negative health outcomes and the comorbidities related to type 2 diabetes. Increased knowledge, awareness and behavior change concerning the benefits of physical activity and eating a healthy diet to control type 2 diabetes. Decreased perceived barriers to physical activity and diet. Increased cues to action, self-efficacy and autonomy to control type 2 diabetes through physical activity and diet. | Unchanged or increased incidence and prevalence of type 2 diabetes in community-dwelling children, adolescents, adults and older adults. Unchanged or increased BMI, blood glucose levels and A1c in community-dwelling children, adolescents, adults and older adults living with or at risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Lack of knowledge and awareness about perceived susceptibility, perceived severity and perceived threat of type 2 diabetes; lack of knowledge and awareness about perceived barriers of type 2 diabetes; lack of knowledge and awareness about cues to action; and lack of self-efficacy for controlling or preventing type 2 diabetes with physical and diet in community-dwelling children, adolescents, adults and older adults living with or at risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Unwillingness to participate in future programs. Lack of confidence and trust in program and future programs. |

| Staff (e.g., educators/lecturers, one-on-one counselors, groups session leaders), community volunteers (e.g., teachers, role models) | Implementation and support of the program. | How/why should we be involved in the program? How much time will we need to invest in the program? What will I achieve or gain from implementing the program? How can I educate participants? Will I do a good job helping to implement the program? | Support in the decrease in the incidence and prevalence of type 2 diabetes in their community-dwelling children, adolescents, adults and older adults living with or at risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Increased skills of educating, holding lectures and groups sessions for community-dwelling children, adolescents, adults and older adults living with or at risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Motivation to continue the program and continue to implement, assist and support the program. | Wasted resources and time. Unwillingness to assist and support program or future programs. Lack of confidence and trust in program and future programs. |

| Community partners (e.g., local schools; local hospitals, clinic and fire stations; local farmer’s markets, gyms and restaurants) | Assist and support program implementation. | Is the program decreasing type 2 diabetes in the community? How can I help people living in the community control or prevent type 2 diabetes? How much time will we need to invest in the program? What will I achieve or gain from assisting and supporting the program? Is the program helpful or harmful to the participants? Will this program cost me any money? Will the program generate customers/revenue for our company? | Assist and support in the decrease in the incidence and prevalence of type 2 diabetes in their community-dwelling children, adolescents, adults and older adults living with or at risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Motivation to continue the program. | Wasted resources and time. Unwillingness to assist and support program or future programs. Lack of confidence and trust in program and future programs. |

Evaluation design

The outcome evaluation design that will be used in this program is a Quasi-Experimental Design consisting of a one-group design with a pre-test and multiple posttests. The pre-test will be administered on the first day of the program implementation. Multiple post-tests will be administered at the 3rd month, 6thmonth, 12thmonth (which is the last day of the intervention).

It would be unethical to withhold or exclude a person or population from an intervention that could improve their lives and the lives around them by controlling or preventing type 2 diabetes, so there will not be a control group.

The treatments will remain the same throughout the year long intervention.

Evaluation design: O1 X O2 X O3 X O4.

[O1=Pre-test, X=Physical Activity and Diet Treatment, O2=3 month Post-test, O3=6 month Post-test, O4=12 month Post-test]

The pre-test and multiple posttests will evaluate the participant’s self-efficacy for physical activity and healthy eating, self-efficacy for self-care of diabetes, perceived benefits of physical activity and healthy eating, perceived barriers for physical activity and healthy eating, knowledge of type 2 diabetes, physical activity behavior change(s) and healthy eating behavior change(s).

In addition to surveys being administered to evaluate the program outcomes, anthropometric measures including participant body mass index (BMI) will be calculated with measurements of weight, height and body fat with calipers and blood samples will also be collected from participants with a multi-test glucometer for blood glucose monitoring and A1c monitoring. These screening measures will also be collected at baseline, at 3 months, 6 months and 12 months.

Threats to Program Internal Validity

Selection threat:

Selection bias can be a treat to internal validity of the program because all participants are volunteers. Motivations for participation could differ and there could be more or less motivation depending on the participant. Therefore participants may share a motivational characteristic that the true population does not share. A way to attenuate this type of threat is to recruit as many participants as possible for the intervention. By increasing the sample size and the stratification of the sample, a more accurate representation of the population can be obtained. Ways to accomplish this could be recruitment from many different places. For example, the present program will be recruiting from local schools, local hospitals, local physician’s offices, local clinics and local health departments.

An additional way to attenuate self-selection bias is to encourage participation that equally rewards all participants. Certificates of completion or awards for program milestones could encourage participation and equally include all participants.

Attrition threat:

Attrition threat can be a treat to internal validity of the program. Due to the length of the intervention and the large range of participants’ age, drop-out is a threat. This program is a community-based intervention. Children, adolescents, adults and older adults are recruited to participate. There can be numerous forms of attrition threat due to the wide range of ages. For example, children may have school related activities, adults may have child care infringements, and older adults attrition could drop due to participant death. Therefore, intended dose might not reach all participants involved in the intervention.

However, ways to attenuate this threat is maintaining consistent contact with participants and creating incentives such as routine checkups for measurement of weight (BMI), blood glucose, A1c and taking surveys every 3 months throughout the intervention. By maintaining close contact with participants, loss to follow-up will also decrease. Further, participants could be lost due to injury during physical activities. Prevention of participant loss from injury is attenuated by training participants to be safe when physically active.

Certificates of completion or awards for program milestones could decrease attrition, encourage participation and equally include all participants.

Testing threat:

Testing threat can be a treat to internal validity of the program. Due to the intervention using pre-posttests at baseline and subsequently at every 3 month interval, testing threat can occur because participants may respond to the surveys in ways that could produce error. For example, participants may respond to surveys in ways they believe the interviewer may wish them to respond. Further, creation and validation of surveys are needed for children to measure self-efficacy for physical activity and self-efficacy for diet and surveys that are translated in other languages (e.g., Spanish).

Outcome Evaluation Surveys

| Short-term or Intermediate Outcome Variable | Scale, Questionnaire, Assessment Method | Brief Description of Instrument | Example Item (for surveys, scales or questionnaires) | Reliability and/or Validity Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-efficacy for exercise in adults | The SCI Exercise Self-Efficacy Scale (ESES) | The ESES is a 10-item 4-point Likert scale for measuring exercise self-efficacy. | “I am confident that I can overcome barriers and challenges with regard to physical activity and exercise if I try hard enough.” | Cronbach's alpha for the ESES was 0.9269. |

| Self-efficacy for diet in adults | The Diet Self-Efficacy Scale (DIET-SE) | The DIET-SE is a 5-point Likert scale used to measure diet self-efficacy. The DIET-SE uses three factors: high caloric food temptations, social and internal factors and negative emotional events. | “You are having a hard day at work and you are anxious and upset. You feel like getting a candy bar. How confident are you that you would find a more constructive way to calm down and cope with your feelings?” | The internal consistency for the DIET-SE ranges from α is 0.82 to 0.87. |

| Self-efficacy of physical activity and diet in children and adolescents | The Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities Measure (SDSCA) | The SDSCA is an 8-point Likert scale that measures physical activity, healthy eating, and blood glucose testing for children and adolescents. | “Eat high fat foods such as red meat or full-fat dairy products.” | Reliability for the SDSCA of overall core items is 0.735. |

| Perceived Benefits and Perceived Barriers to physical activity in adults | Exercise Benefits and Barriers Scale (EBBS) [Adult version] | The EBBS is a 4-Likert scale with 43-items measuring perceived Benefits and perceived Barriers to physical activity. | “Exercise decreases feelings of stress and tension for me.” | The Cronbach’s alpha for the total scale was 0.927 and benefits was 0.94 and barriers was 0.82. |

| Perceived Benefits and Perceived Barriers to physical activity in adolescents | The Adolescent Physical Activity Perceived Benefits and Barriers Scales | The Adolescent Physical Activity Perceived Benefits and Barriers Scales are a 10-item Perceived Benefits Scale and the 9-item Perceived Barriers Scale. | Perceived Benefits item: I prove to myself what I can do physically.” | Cronbach’s alpha was 0.80 for the Perceived Benefits Scale and 0.79 for the Perceived Barriers Scale. |

| Perceived Benefits and Perceived Barriers to eating fruits and vegetables | Decisional Balance Scale | The Decisional Balance Scale a 5-point Likert scale that measures perceived benefits and perceived barriers to eating fruits and vegetables. | “My family would think I was fussy if I ate more vegetables instead of other foods such as meat or seafood.” | Cronbach's alpha for benefits was 0.86 and Cronbach's alpha for barriers was 0.79. |

| Measuring baseline knowledge for adults about diabetes and changes about knowledge during the intervention | Short Diabetes Knowledge Instrument (SDKI) | The SDKI is a 16-item questionnaire to evaluate knowledge about diabetes. | “Healthy eating for a person with diabetes means: eating less animal fat.” | Cronbach’s alpha was 0.73. |

| Physical Activity Behavior/Intention and motivation to exercise | Intention to Exercise Scale | The Intention to Exercise Scale is a 7-point scale measuring intention to be physically active through the attitude toward exercise; support by significant other persons; perception of control, and motivation to exercise. | “Physical fitness activities improve my physical health.” | Cronbach’s is alpha=0.87. |

| Healthy eating Behavior | The Healthy Eating and Health Behavior Questionnaire (HEHBQ) | The HEHBQ is a 6-point scale measuring healthy eating by measuring healthy eating and health behaviors, unhealthy eating and health risk behaviors and self-health monitoring of healthy eating. | “How often can you eat vegetables and fruits as much as one-half of plate?” | Cronbach’s alpha for healthy eating and health behaviors was 0.69, 0.72 for unhealthy eating and health risk behaviors and 0.79 for self-health monitoring. |

Scales added to Outcome Evaluation Surveys/Measurements:

Intention to Exercise Scale, Short Diabetes Knowledge Instrument (SDKI), Decisional Balance Scale and The Healthy Eating and Health Behavior Questionnaire (HEHBQ).

Part V: Process Evaluation and Data Collection Forms

Recruitment and Enrollment

Adult/Older Adult Recruitment and Enrollment Form Sample Letter: Form will be given to local schools, local hospitals, local clinics, local gyms and local health department for participant recruitment.

Child/Adolescent Recruitment and Enrollment Form Sample Letter: Form will be given to local schools to be sent home with students for parent/guardian for participant recruitment.

Community Partner Recruitment and Enrollment Form: Form will be given to local school, local hospitals, local clinics, local health department, local gyms, local farmer’s markets and local restaurants.

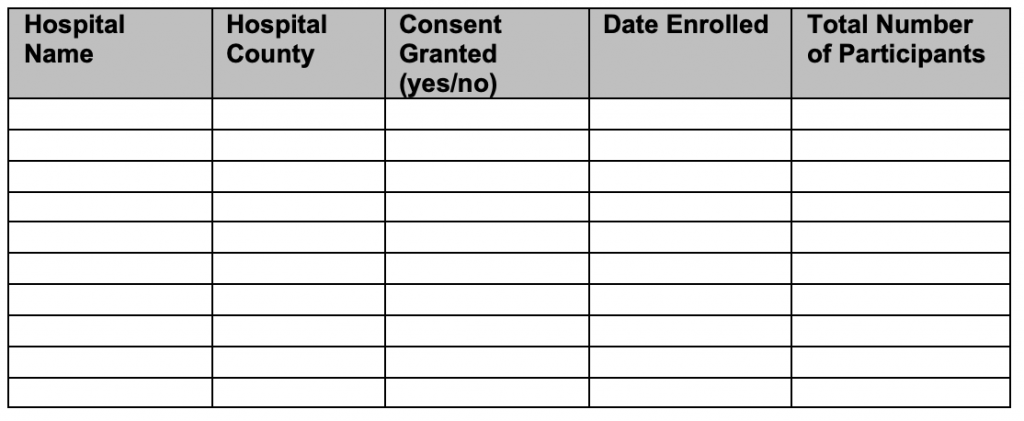

Enrollment Forms: Local Hospitals

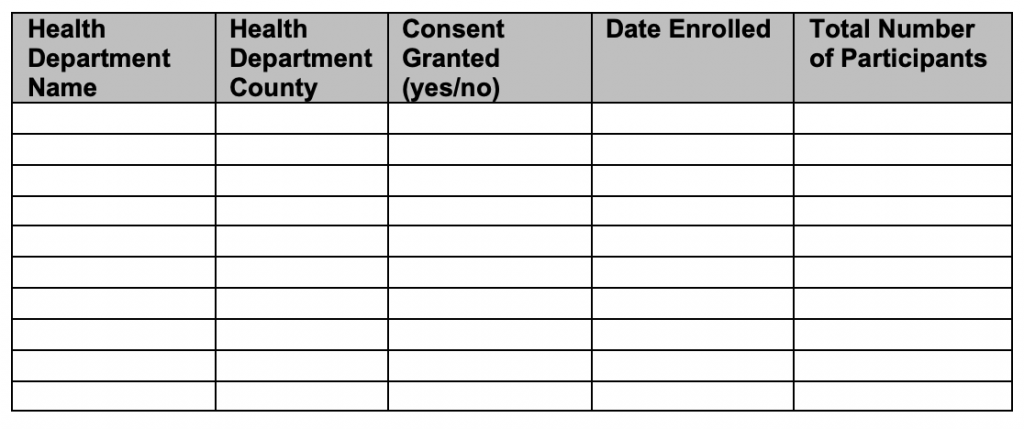

Enrollment Forms: Local Health Department

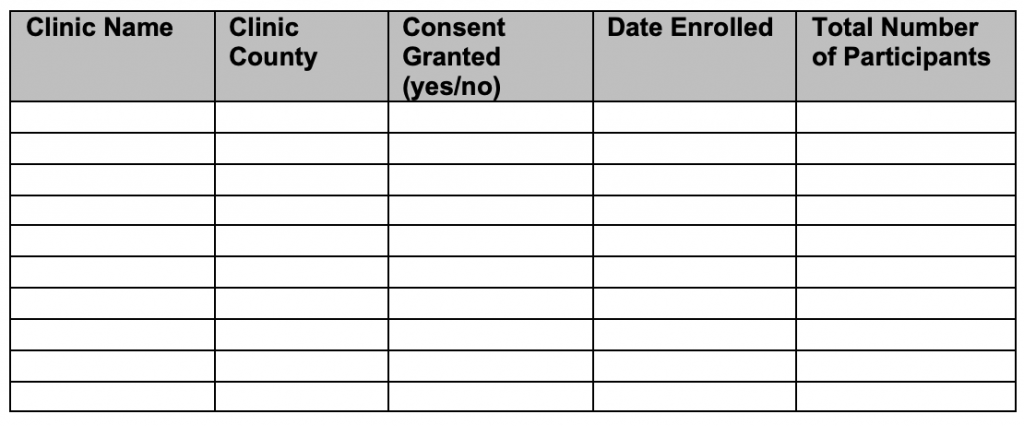

Enrollment Forms: Local Clinics

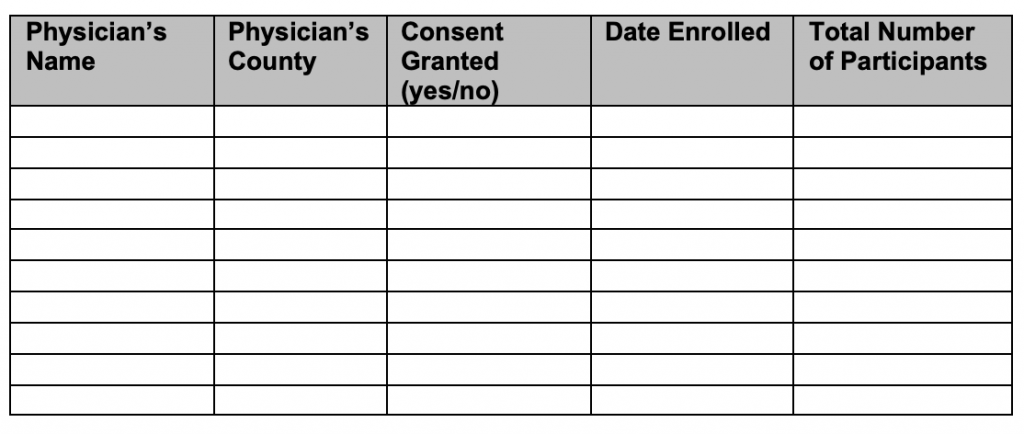

Enrollment Forms: Local Physician’s Office

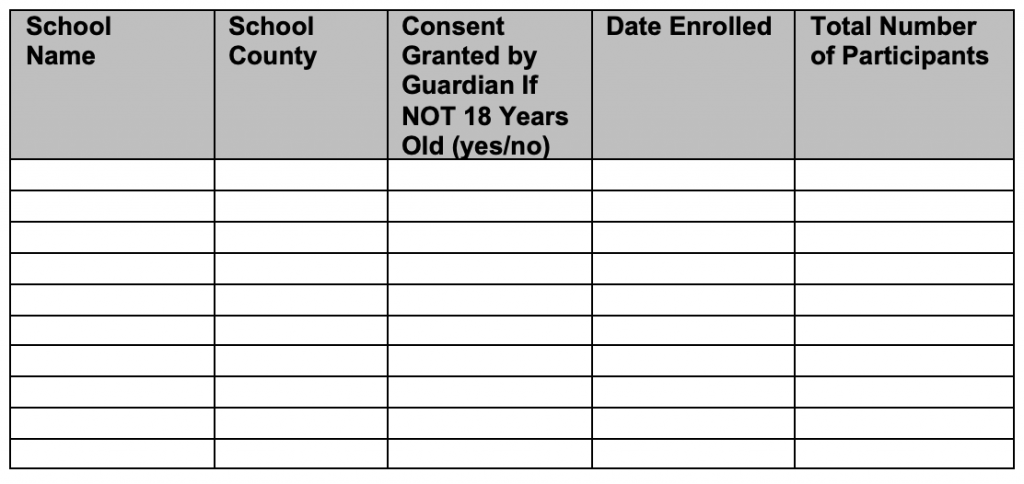

Enrollment Forms: Local School

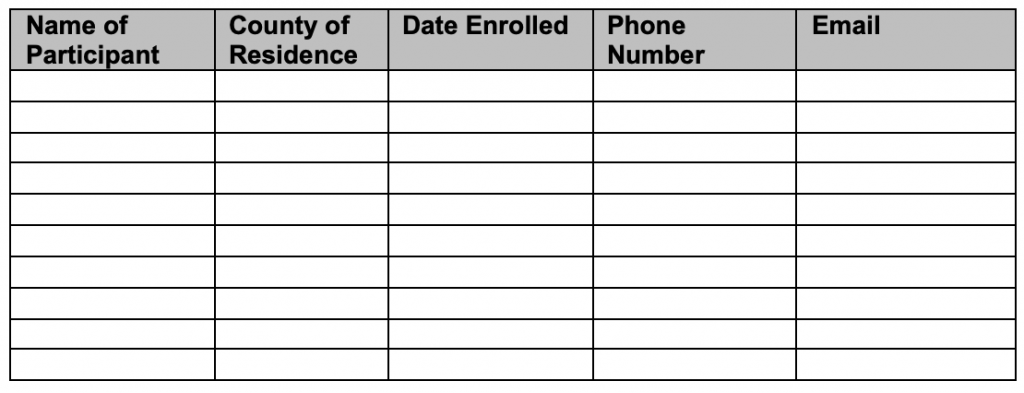

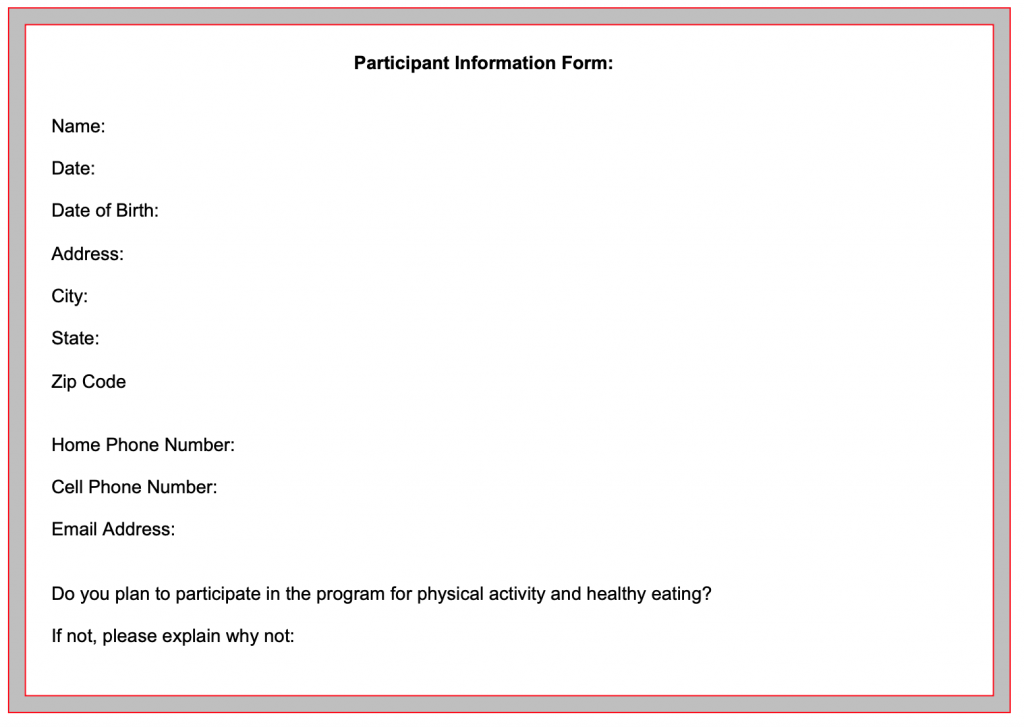

Enrollment Forms: Individual

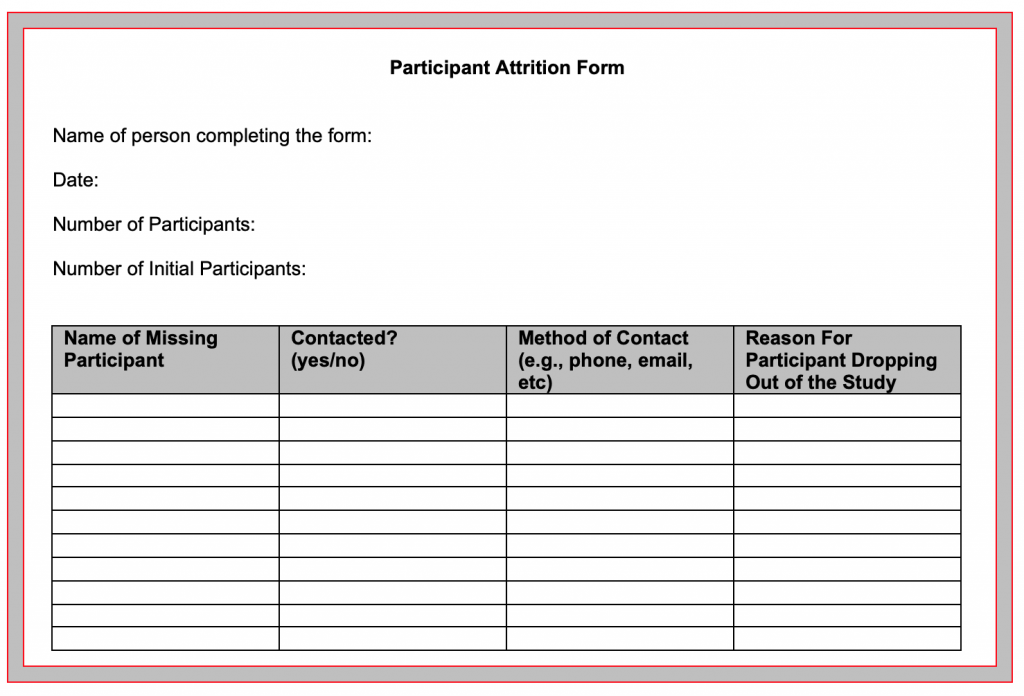

Attrition:

Attrition Prevention form will be given to participants (at the beginning of the program) for completion to maintain contact. Reminders of posttests will be mailed to participants.

Participant Attrition Form: Forms to be completed at each post-test (3, 6 and 12 months)

Fidelity of the Program

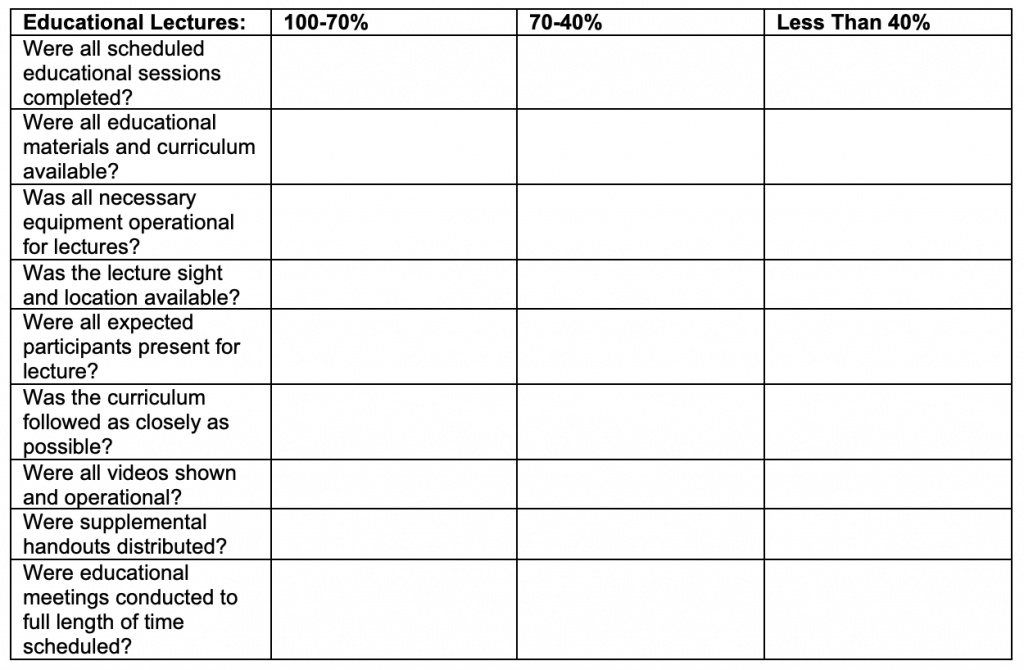

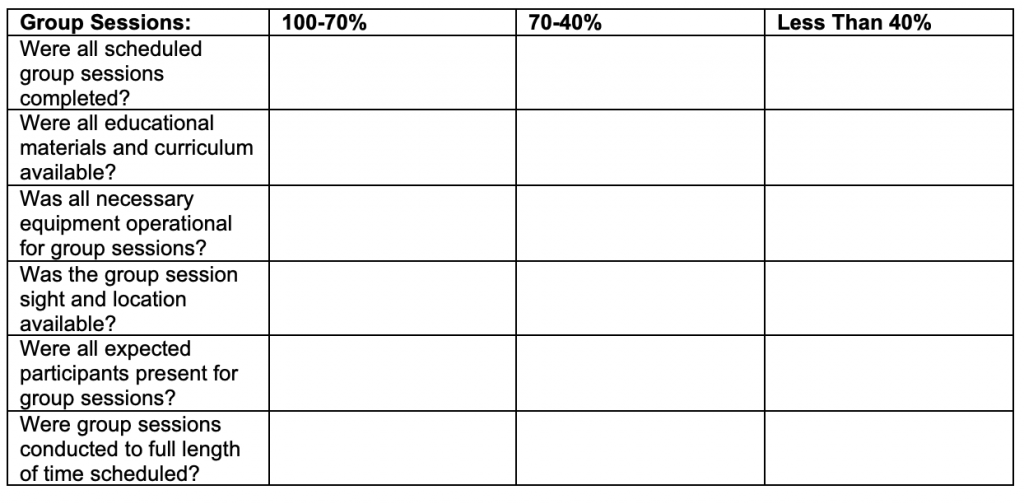

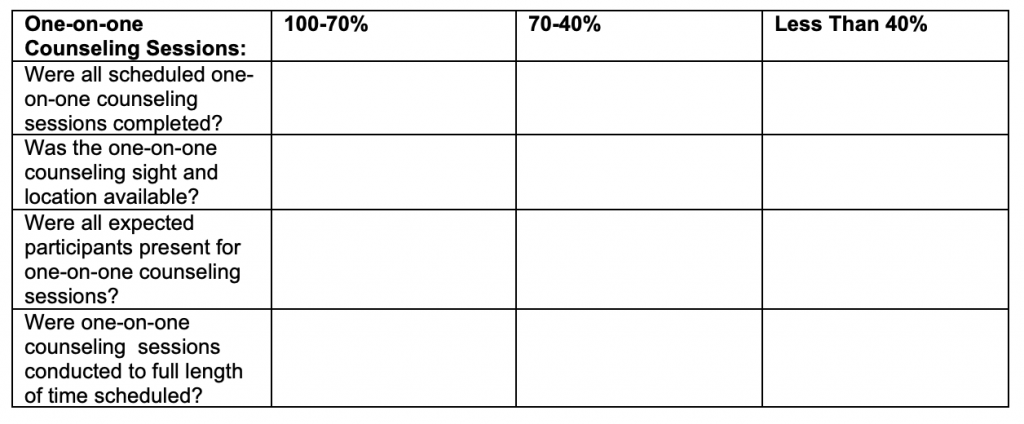

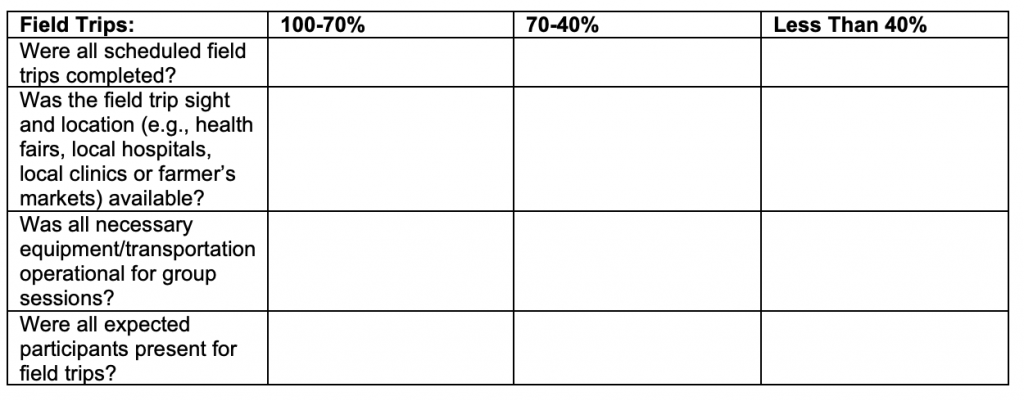

Program Fidelity Checklist: Forms to be filled outgroup leaders and/or counselors.

References:

Addressing Health Disparities in Diabetes. (2018, September 25). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/disparities.html.

Annie Mei Chuan, L., & Horwath, C. (2001). Perceived Benefits and Barriers of Increased Fruit and Vegetable Consumption: Validation of a Decisional Balance Scale. Journal of Nutrition Education, 33(5), 257. doi:10.1016/S1499-4046(06)60289-3.

Bhupathiraju, S. N., & Hu, F. B. (2016). Epidemiology of Obesity and Diabetes and Their Cardiovascular Complications. Circulation Research (Vol. 118, pp. 1723-1735).

Chavasit, V., Yamborisut, U., Sridonpai, P., Photi, J., Meenongwah, J., & Visetchart, P. (1). Reliability of Healthy Eating and Health Behavior Questionnaire for Thai Adults. Journal of Health Research, 29(5), 341-349. Retrieved from https://www.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/jhealthres/article/view/97197.

Ely, E. K., Gruss, S. M., Luman, E. T., Gregg, E. W., Ali, M. K., Nhim, K., Albright, A. L. (2017). A National Effort to Prevent Type 2 Diabetes: Participant-Level Evaluation of CDC’s National Diabetes Prevention Program (Vol. 40, pp. 1331-1341).

Gallé, F., Onofrio, V. D., Miele, A., Belfiore, P., & Liguori, G. (2019). Effects of a community-based exercise and motivational intervention on physical fitness of subjects with type 2 diabetes. European Journal of Public Health, 29(2), 281-286. doi:10.1093/eurpub/cky140.

Garcia, A. W., Pender, N. J., Antonakos, C. L., Ronis, D. L., Garcia, A. W., Pender, N. J., Ronis, D. L. (1998). Children’s Perceived Benefits/Barriers to Physical Activity Questionnaire. Changes in physical activity beliefs and behaviors of boys and girls across the transition to junior high school, 22, 394-402.

Glanz, K., Rimer, B. K., & Viswanath, K. (2015). Health behavior: theory, research, and practice: San Francisco, CA : Jossey-Bass, [2015] Fifth edition.

Jalaludin, M. Y., Fuziah, M. Z., Hong, J. Y. H., Mohamad Adam, B., & Jamaiyah, H. (2012). Reliability and Validity of the Revised Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities (SDSCA) for Malaysian Children and Adolescents. Malaysian Family Physician(2&3), 10.

Kerner, M. S., & Grossman, A. H. (2001). Scale construction for measuring attitude, beliefs, perception of control, and intention to exercise, 124.

Kroll, T., Kehn, M., Pei-Shu, H., & Groah, S. (2007). The SCI Exercise Self-Efficacy Scale (ESES): development and psychometric properties. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition & Physical Activity, 4, 34-36. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-4-34.

Leila Amiri, F., Soroor, P., Eesa, M., Mohsen, A.-L., Anoshiravan, K., Seyede Batool, H.-A., & Ziba, T. (2017). The psychometric properties of exercise benefits/barriers scale among women. Electronic Physician(7), 4780. doi:10.19082/4780.

Mendes, R., Sousa, N., Themudo-Barata, J., & Reis, V. (2016). Impact of a community-based exercise programme on physical fitness in middle-aged and older patients with type 2 diabetes. 30(3), 215-220. doi:10.1016/j.gaceta.2016.01.00.

Ohlsson, B. (2019). An Okinawan-based Nordic diet improves glucose and lipid metabolism in health and type 2 diabetes, in alignment with changes in the endocrine profile, whereas zonulin levels are elevated (Review). Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine(4), 2883. doi:10.3892/etm.2019.7303.

Salas-Salvadó, J., Díaz-López, A., Ruiz-Canela, M., Basora, J., Fitó, M., Corella, D., Tinahones, F. J. (2019). Effect of a Lifestyle Intervention Program With Energy-Restricted Mediterranean Diet and Exercise on Weight Loss and Cardiovascular Risk Factors: One-Year Results of the PREDIMED-Plus Trial. Diabetes Care, 42(5), 777-788. doi:10.2337/dc18-0836.

Stich, C., Knaeuper, B., & Tint, A. (2009). A Scenario-Based Dieting Self-Efficacy Scale The DIET-SE (Vol. 16, pp. 16-30).

Quandt, S. A., Ip, E. H., Kirk, J. K., Saldana, S., Chen, S.-H., Ha, N., Arcury, T. A. (2014). Assessment of a Short Diabetes Knowledge Instrument for Older and Minority Adults (Vol. 40, pp. 68-76).