*Red lettering indicates edits* * Italics indicate edits within tables*

Part I. Community Guide Update and Rationale for Intervention

| Author & Year | Intervention Setting, Description, and Comparison Group(s) | Study Population Description and Sample Size | Effect Measure (Variables) | Results, including Test Statistics and Significance | Follow-up Time |

| Fellow et al., 2018 | Individuals who opted to participate were from a hospital in Europe. During the participants prenatal checkups, blood samples were taken and information on folic acid supplementation was recorded. Participants who took folic acid supplements were compared against participants who did not take supplements. | The sample size was 502 women, who have not had multiple pregnancies, no history of neural tube defects, and were able to understand English. The study population represented a variety of socioeconomic and geographic backgrounds. | Effect measures included whether or not participants took folic acid supplements, the dosage of the folic acid supplements, RBC folate levels, serum folate levels, and whether or not there was a neural tube defect outcome. | Of all the women in the study, 98.2% took folic acid supplements; there were zero neural tube defect outcomes. A significant correlation was found between duration of folic acid supplementation and RBC folate (r = 0.43, P < 0.001), as well as serum folate (rho = 0.29, P < 0.001). RBC folate levels have been demonstrated to be important in preventing neural tube defects. | After subjects’ blood samples were taken, follow-up did not occur until birth. |

| Turgul et al., 2009 | This intervention took place in Narlidere, Izmir, Turkey within several healthcare centers and schools in March through November 2006. This intervention campaign was titled “Educating Women on Neural Tube Defects for Safe Motherhood and Healthy Generations,” and was aimed at increasing knowledge on and encourage the use of folic acid. Seminars, interviews, advertisements, pamphlets, and home visits were utilized to accomplish this. No control group was used. | A total of 4387 randomly selected females participated. Participants were required to be females of reproductive age, living in Narlidere, Turkey, near 3 of the local healthcare centers (from which they were randomly selected from based on records). Between the three centers, a variety of socioeconomic statuses were represented. | Effect measures included knowledge of folic acid and neural tube defects, use of folic acid supplementation, and other demographic and behavioral variables. | Only 18% of participants knew what folic acid was prior to the intervention, and only 19% had taken any supplements during pregancy. After the intervention, knowledge surrounding folic acid and neural tube defects increased significantly (t = 141.320; p < 0.0001). No effect size was listed. | Specific follow-up time was not stated, however, the intervention took place March-November 2006. |

| Felkner et al., 2005 | This intervention took place in Texas, bordering Mexico. The Texas Department of Health developed a folic acid intervention to provide knowledge on supplementation in the context of preventing neural tube defects, especially among Mexican-American individuals. No control group was used in this intervention. | There were a total of 299 women who had neural tube defect affected pregnancies who participated in the intervention; 161 of these women became pregnant during observation. | Effect measures included folic acid supplementation, RBC folate, serum B12, and neural tube defect outcome. | Among the women who participated in folic acid supplementation, no neural tube defects were detected. No statistical analysis were preformed. | Participants were followed-up at 3-month intervals during pregnancy, and lasted until 4 months post-partum. |

2) The importance of community-wide campaigns in spreading the awareness of neural tube defects and knowledge of folic acid supplementation is also expressed in the original recommendation by the Community Preventative Task Force (CPTF), as well as in the updated evidence. The CPTF’s recommendations are in agreement with the updated recommendations from the evidence above, recommending that community-wide educational programs be used to promote the use of folic acid supplementation in women. It has been determined that based on the reviewed evidence that this strategy be updated to strongly recommended to make a recommendation for the supplementation of folic acid to prevent the occurrence of a neural tube defect outcome.

3) The Community Preventative Services Task Force previously recommended based on sufficient evidence from a systematic review of 24 studies that community-wide campaigns to promote folic acid supplementation is correlated with an increase in supplementation and a decrease in neural tube defect outcomes. The recommendations above, of including a specific folic acid dosage and including community-wide campaigns in intervention strategies is justified based on both the recent evidence finding significant results, and in the CPTF’s recommendation (Turgul et al., 2009). Due to the continued, recent publication of evidence in support of improved neural tube defect outcomes and increased folic acid supplementation, the recommendation level was changed, from recommended to strongly recommended to make a recommendation of using community-wide campaigns to promote the use of folic acid supplementation (Fellow et al., 2018; Felkner et al., 2005).

Part II. Theoretical Framework/Model

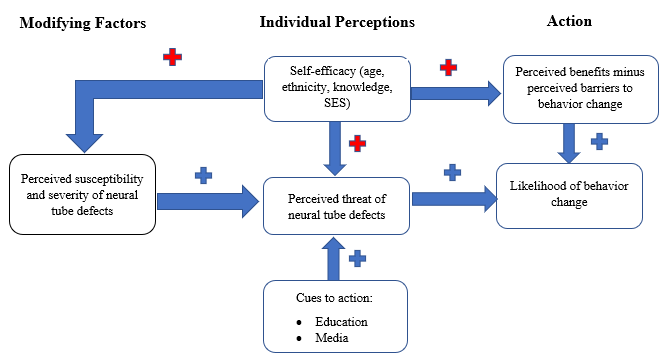

4) The Health Belief Model is an individual level theory which includes constructs which, when aimed at promoting folic supplementation, would increase the behavior of folic acid supplementation and decrease the occurrence of neural tube defects. Constructs include: perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, self-efficacy, and cues to action. These constructs are aimed at knowledge of neural tube defects and providing individuals with the education to prevent them.

Perceived susceptibility: This construct includes an individual’s level of perceived vulnerability. The more an individual feels susceptible or vulnerable to neural tube defects in their child, the more one may be inclined to take action to increase a preventative behavior, such as taking folic acid supplements. This construct could be increased or decreased by self-efficacy, depending on individual characteristics.

Perceived severity: An individual’s perceived severity of neural tube defects may be affected by their perceived susceptibility, threat, and/or self-efficacy. Self-efficacy factors such as previous knowledge on neural tube defects may be a determining factor in how severe an individual perceives neural tube defects to be. The more an individual perceives the severity of neural tube defects to be, the more likely it is for an individual to increase the behavior of folic acid supplementation.

Perceived benefits: Depending on the level of knowledge of neural tube defects, individuals may perceive that benefits of folic acid supplementation are a significantly reduced risk of neural tube defects in their infants. Perceived benefits may be affected by perceived barriers and self-efficacy. If there are significant barriers present, likelihood of behavior change may be decreased.

Perceived barriers: Perceived barriers may include lack of access to folic acid supplements, lack of ways to obtain the supplements (no transportation or money), or the individual may feel that they don’t know enough about supplementation. Perceived barriers pertaining to folic acid supplementation may be affected by self-efficacy and may be a significant reason why individuals do not begin folic acid supplementation. Barriers such as those listed can be overcome with cues to action.

Self-efficacy: This construct includes factors about an individual which may effect the likelihood of behavior change, or using folic acid supplements. Factors may include: age, ethnicity, knowledge, or SES. Self-efficacy can have a direct, positive or a negative effect on perceived susceptibility and severity, perceieved threat, and perceived benefits.

Cues to action: Cues to action are actions taken in the form of education and media to promote the use of folic acid supplements. Education may be in the form of fliers/pamphlets, seminars, or word of mouth, while media may be in the form of advertisements promoting folic acid supplementation or social media campaigns. Cues to action spread awareness on neural tube defects which can increase perceived threat and increase the likelihood of behavior change.

5) Health Belief Model (HBM)

Part III. Logic Model, Causal and Intervention Hypotheses, and Intervention Strategies

6) The target population for this intervention is females of reproductive age, living in rural areas within the United States. This population is a health disparate group due to lack of resources and large prevalence of low-income families within rural areas. Research has demonstrated that women from areas with low socioeconomic and limited educational backgrounds score lower on folic acid knowledge tests, thus these populations should be targeted for intervention (F = 15.40; p < 0.0001) (Turgul et al., 2009). The intervention setting will consist of information sessions/seminars, ads on television and radio, and pamphlets and flyers being passed out in busy places such as grocery stores and common municipal areas.

7) Intervention methods for the program are derived from the Health Belief Model (HBM), and each strategy will be essential for successful implementation and promotion of folic acid supplementation. Methods include (1) increasing knowledge of neural tube defects and folic acid supplements, (2) increasing self-efficacy, and (3) reinforcing the behavior change. These methods align with the HBM in the following ways; (1) increasing knowledge of neural tube defects and folic acid supplementation acts as cues to action in increasing knowledge of susceptibility and severity of neural tube defects, (2) increasing self-efficacy pertains to perceived susceptibility, severity, threats, benefits, and barriers to folic acid supplementation to reduce the likelihood of neural tube defects, and (3) reinforcing behavior change acts as cues to action in reinforcing the likelihood of folic acid supplementation.

8) Intervention Strategies:

| Intervention Method | Alignment with Theory | Intervention Strategy |

| Increasing knowledge of neural tube defects and folic acid supplements | Increasing knowledge surrounding folic acid supplements and neural tube defects aligns with the Health Belief Model by acting as cues to action in increasing knowledge of susceptibility and severity of neural tube defects, promoting the behavior of taking folic acid supplements. | Community-based information seminars, ads on television and radio, and pamphlets/flyers. These resources will contain information regarding what neural tube defects are, what folic acid supplements are, and how to reduce the risk of having a child born with neural tube defects by taking folic acid supplements as a preventative approach. |

| Increase self-efficacy | This intervention strategy is derived from the Health Belief Model, and contains factors involved in knowledge surrounding perceived susceptibility, severity, threats, benefits, and barriers to promoting the use of folic acid supplementation to reduce to risk of neural tube defects. | Self-efficacy can be increased by having pop-up tents in high traffic areas, such as grocery stores or common municipal areas, with healthcare professionals to answer questions, pass out pamphlets, and promote conversation about neural tube defects and folic acid supplementation with residents. |

| Reinforcing the behavior change | Once the likelihood of behavior change has reached the point of actual behavior change (i.e. regular use of folic acid supplements has occurred), cues to action in the form of regular reminders continually reinforce the likelihood of this behavior change. | Cues to action to reinforce the continuation of utilizing folic acid supplements will be in the form of reminders and discussions with women of reproductive age at doctors offices and other healthcare centers, posters promoting folic acid supplementation around town, and reminders in the form of letters and e-mails for those who sign up (sign-up may occur at any seminars, pop-up tents, or online via a website listed on flyers, pamphlets, and posters). |

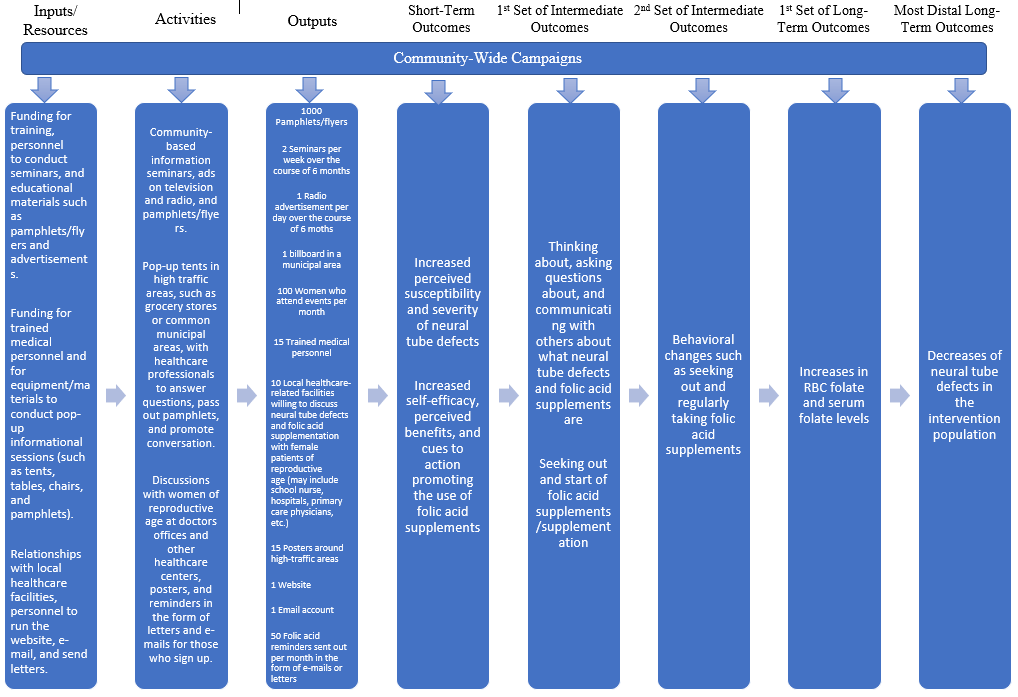

9) Logic Model:

10) Intervention and Causal Hypotheses:

Intervention hypothesis: Activities such as seminars, advertisements on radio and television, pamphlets, flyers, and posters will lead to the short-term outcomes of increased perceived susceptibility and severity of neural tube defects. Activities such as pop-up tents conducting question and answer sessions, as well as letter/e-mail reminders will lead to increased self-efficacy, perceived benefits, and cues to action promoting the use of folic acid supplements.

Causal hypothesis: The lack of utilizing folic acid supplements for the purpose of preventing neural tube defects is due to 1) a lack of knowledge surrounding neural tube defects and folic acid supplements, 2) a lack of self-efficacy, and 3) a lack of support and cues to action such as community-wide education or reminders to reinforce the behavior change of taking folic acid supplements regularly.

Increases in the short-term outcomes of perceived susceptibility and severity of neural tube defects, as well as the increased self-efficacy, perceived benefits, and cues to action promoting the use of folic acid supplements will lead to improvements in the intermediate outcomes of thinking about, asking questions about, and communicating with others about what neural tube defects and folic acid supplements are, as well as behavioral changes such as seeking out and regularly taking folic acid supplements. These intermediate outcomes will later lead to the long-term outcomes of increases in RBC folate and serum folate levels, as well as decreases of neural tube defects in the intervention population.

11) SMART Outcome Objectives:

Goal 1: Increasing knowledge of folic acid supplements and neural tube defects.

- Objective 1: 3 months after program implementation, 50% of females of reproductive age involved in the program will report having feelings of increases in self-efficacy, perceived susceptibility, decreases in perceived barriers, and are able to discuss what neural tube defects and folic acid supplements are; these changes in short-term outcomes will be determined based on pre- and post-test responses.

- Objective 2: 6 months after program implementation, 90% of females of reproductive age involved in the program will report having feelings of increases in self-efficacy, perceived susceptibility, decreases in perceived barriers, and are able to discuss what neural tube defects and folic acid supplements are; these changes in short-term outcomes will be determined based on pre- and post-test responses.

Goal 2: Increase the number of females of reproductive age seeking out folic acid supplements.

- Objective 1: 6 months after program implementation, 75% of females of reproductive age involved in the program will begin to seek out folic acid supplements and have increases in perceived benefits of taking folic acid supplements.

Goal 3: Increase communication and asking questions about folic acid supplementation and neural tube defects.

- Objective 1: 3 months after program implementation, 50% of females of reproductive age involved in the program will report having feelings of increased susceptibility and perceived severity of neural tube defects, leading to increases in communication and asking questions about folic acid supplements and neural tube defects with others; these changes in short-term outcomes will be determined based on pre- and post-test responses.

- Objective 2: 6 months after program implementation, 95% of females of reproductive age involved in the program will report having feelings of increased susceptibility and perceived severity of neural tube defects, leading to increases in communication and asking questions about folic acid supplements and neural tube defects with others; these changes in short-term outcomes will be determined based on pre- and post-test responses.

Goal 4: Increases in sustained use of folic acid supplements.

- Objective 1: 6 months after program implementation, 40% of females of reproductive age involved in the program will be taking folic acid supplements regularly due to cues to action and lower perceived barriers.

- Objective 2: One year after program implementation, 60% of females of reproductive age involved in the program will be taking folic acid supplements regularly due to cues to action and lower perceived barriers

Goal 5: Increases in RBC folate and serum folate levels.

- Objective 1: 6 months after program implementation, 20% of females of reproductive age involved in the program will have optimal RBC folate and serum folate levels of at least 25.5 nmol/L (Chen et al., 2019).

- Objective 2: One year after program implementation, 40% of females of reproductive age involved in the program will have optimal RBC folate and serum folate levels of at least 25.5 nmol/L (Chen et al., 2019).

Part IV. Evaluation Design and Measures

12) Stakeholders

| Stakeholder | Role in Intervention | Evaluation Questions from Stakeholder | Effect on Stakeholder of a Successful Program | Effect on Stakeholder of an Unsuccessful Program |

| Women of reproductive age | Participants receiving the benefits of the program | How will my participation in the program affect my health? Will my participation in this program result in a decreased risk of neural tube defects in my future children? | Participants will have a decreased risk of having a child with a neural tube defect. Participants will become more health-concious. | Lack of a reduction in neural tube defects within the population. Females of reproductive age within the community will not receive appropriate information on folic acid supplements and neural tube defects. |

| Educators/ seminar lecturers | Providing knowledge to participants and assisting in program implementation | How much effort will I be putting into this program? How much interaction will I have with program participants? Will I need to produce the educational material? How effective is the program? | Increased knowledge of neural tube defects and folic acid supplements. Ability to communicate with others about the benefits of folic acid supplements. | Decreased confidence in health-based programs. Decreased motivation to provide time and effort into other programs. |

| Program coordinators | Implementing the program | How much will this program cost? How much time and effort will the program require? What are the expected results? | Increased confidence in the program and willingness to expand the program into other communities. | Decreased confidence in the program’s methods and intervention strategies. Desire to re-evaluate the program to attempt re-implementation. |

| Medical personnel | Providing knowledge to participants, answering participant questions, and assisting in program implementation | How much interaction will I have with the participants? | Continuation of spreading awareness about folic acid supplements and neural tube defects. | Decreased motivation to continue supporting programs. |

| Community partners (such as local healthcare facilities) | Supporting program implementation by providing materials, physical space, and communicating with participants | Will the program curriculum interfere with other events in the community? Will it cost the partner anything? How will the program benefit us? | Continuing support of programs in the community. Increased community awareness and knowledge of neural tube defects and folic acid supplements. | Decreased motivation to continue supporting future programs. Lack of a reduction in neural tube defects within the community’s population. |

13) Evaluation Design

The study design is a multiple post-test, randomized control group design with one treatment group, one control group, pre-test and three post-tests. The treatment and control groups will consist of towns containing individuals of the target population. Those in the treatment group will receive community-wide campaigns for folic acid supplementation, while the control group will not. Randomization will be done in higher order units of entire towns meeting the demographics of the target population; towns selected must not be neighboring, in order to prevent the campaigns from affecting the control group.

R O1 X O2 O3 O4

R O1 O2 O3 O4

[O1: pre-test; O2: post-test at 3 months; O3: post-test at 6 months; O4: post-test at 1 year]

Threats to Internal Validity:

The use of a randomized control design minimizes threats to internal validity by utilizing group randomization, a control group, pre-test, and post-tests. Some threats to internal validity which still exist include history, attrition, and testing. These are a threat because each of these factors can affect the results of both control and treatment groups despite randomization. Using a control group (as comparison to the treatment group) and randomization theoretically allows for the equal distribution of individuals on a number of factors (demographic, for example), thus attenuating the threat of history. Attrition can be attenuated by making events easy to access and comparing pre-test and post-test data to examine if there are any significant characteristics in drop-outs. Incentives may also be used to minimize attrition, such as reduced-cost medical care for those who enroll in the program (regardless of participation); this incentive will also be offered to the control group after the program in completed. Testing bias may be worsened by utilizing pre-tests, however, if questions are worded differently between tests, questions are in different order from pre- to post-tests, the tests that are given to the treatment group are also given to the control group, and we accumulate a large enough sample size, testing bias can be mitigated.

14)

| Short-term or Intermediate Outcome Variable | Scale, Questionnaire, Assessment Method | Brief Description of Instrument | Example item (for surveys, scales, or questionnaires) | Reliability and/or Validity Description |

| Perceived susceptibility to neural tube defects Perceived severity of neural tube defects Folic acid supplementation | Folic acid awareness questionnaire (Nawapun & Phupong, 2007) | This questionnaire was comprised of four sections, designed to assess the knowledge, understanding, and use of folic acid supplements in pregnant women 18-45 years old for the purpose of preventing neural tube defects. Questionnaires also collected data on demographics, folic acid use in the periconceptional period, folic acid use in the antenatal period, and plans to take folic acid supplements in the future. | Perceived susceptibility: “I worry about having a baby with a neural tube defect.” Perceived severity: “I believe that a neural tube defect is a serious condition.” Folic acid supplementation: “I have regularly taken folic acid supplements in the past.” | Face validity and reliability were determined using a pilot program (no Cronbach’s alpha listed). |

| Self-efficacy Perceived benefits Cues to action | ‘Folic Acid Campaign’ questionnaire (van der Pal-de Bruin et al., 2003) | Questionnaire designed to assess education and social influence surrounding folic acid use. This questionnaire was aimed at women wishing to conceive, primarily in low socio-economic areas. Questions consisted of yes/no, open-ended, and Likert scale questions. | Self-efficacy: “I am confident that I could take folic acid supplements regularly.” Perceived benefits: “I believe that taking folic acid supplements would reduce the risk of neural tube defects in my baby.” Cues to action: “Medical staff regularly ask me about my folic acid supplement use.” | Internal reliability: Perceived safety= 0.88 Subjective norm= 0.89 |

Part V. Process Evaluation and Data Collection Forms

15) Data collection forms:

1. Recruitment and Enrollment:

a. City Recruitment: City officials will receive a letter detailing the purpose of the campaign and ask for permission to conduct the campaign in the city.

Community-Wide Campaigns to Promote the Use of Folic Acid Supplements

City Recruitment Letter

Dear__________________,

The University of Georgia School of Public Health’s health promotion students would like to request your city partnership in a community-wide campaign to promote the use of folic acid supplements in females of reproductive age living within your city for the purpose of reducing the risk of neural tube defects in children. Your participation is voluntary, and community activities would include community education in the form of seminars, posters posted around town, advertisements on television/radio, pamphlets/flyers being distributed, question and answer sessions around town, promotion of discussions in healthcare settings, and letter/e-mail folic acid supplementation reminders. This program would last 6 months, with participant follow-up at one year post-intervention. There are no known risks associated with this intervention, and benefits to the community would include a reduction of neural tube defects in children.

For more information, or you would like your city to participate, please contact 706-FOL-ACID or e-mail folicacidcampaign@uga.edu

Sincerely,

Health Promotion at UGA

University of Georgia School of Public Health

City Enrollment Form:

| City Name, State, Zip Code | City Contact Name | City Contact Phone Number |

b. Participant Recruitment: After obtaining consent from the city to conduct the campaign, cities will be randomly assigned to be either a treatment or control. Potential participants (females of reproductive age living within the determined cities) will receive a letter describing the campaign and providing details on an information session on how to participate in the campaign.

Community-Wide Campaigns to Promote the Use of Folic Acid Supplements

Participant Recruitment Letter

Dear _________________,

In partnership with [City Name] and the University of Georgia School of Public Health, health promotion students would like to request your participation in a community-wide campaign to promote the use of folic acid supplements in females of reproductive age for the purpose of reducing the risk of neural tube defects in children.

Your participation is voluntary, and participation would include community education in the form of seminars, question and answer sessions around town, discussions in healthcare settings, and letter/e-mail folic acid supplementation reminders. This program would last 6 months, with participant follow-up at one year post-intervention. There are no known risks associated with this intervention, and benefits would include a reduction in risk of neural tube defects in your future children.

All data collected will be kept confidential and no identifying information will be published.

If you would like to participate in the campaign, please call (706-FOL-ACID), e-mail (folicacidcampaign@uga.edu), or bring this form to the information session held:

June 6th, 2019 from 7:00-8:00 pm

at the University of Georgia, Health Sciences Campus

Russell Hall, Room 101

Name____________________________

Date of Birth_______________________

Phone number__________________

E-mail_________________________

For more information or questions, please call 706-FOL-ACID or e-mail folicacidcampaign@uga.edu

Sincerely,

Health Promotion at UGA

University of Georgia School of Public Health

Participant Enrollment Form:

City name:___________________

| Participant ID | Participant Name | DOB | Phone Number | Date enrolled | |

c. Local Healthcare Partners’ Recruitment: Local healthcare providers including hospitals, school nurses, doctors offices, and other health clinics within city limits will receive letters describing the campaign and requesting partnership. Partnership would include communicating with patients regarding the importance of folic acid for reducing the risk of neural tube defects and providing physical space for community events.

Community-Wide Campaigns to Promote the Use of Folic Acid Supplements

Local Healthcare Partners Recruitment Letter

Dear_______________,

The University of Georgia School of Public Health’s health promotion students would like to request your local healthcare partnership in a community-wide campaign to promote the use of folic acid supplements in females of reproductive age living within your city for the purpose of reducing the risk of neural tube defects in children. Your participation is voluntary, and participation would include, pamphlets/flyers being distributed, question and answer sessions around town twice a month, and promotion of discussions about folic acid and neural tube defects within your healthcare setting. This program would last 6 months, with participant follow-up at one year post-intervention. There are no known risks associated with this intervention, and benefits to the community would include a reduction of neural tube defects in children.

If you would like to participate in the campaign or have further questions, please call (706-FOL-ACID) or e-mail (folicacidcampaign@uga.edu).

Sincerely,

Health Promotion at UGA

University of Georgia School of Public Health

Healthcare Partnership Enrollment Form:

City Name:_____________________

| Hospital Name | Hospital Contact Name | Hospital Contact Number | Hospital Contact E-Mail |

2. Attrition:

a. Form to be given to participants at each event held:

Name ___________________ Date _____________

Date of Birth ______________ Primary Telephone ________________

Secondary Telephone ________________ E-mail ________________

City, State, and Zip code of Residence __________________________

Would you like to be enrolled in the community-wide campaign to promote the use of folic acid supplements, if not already? (Circle one): Yes / No

b. Form to be completed by event leaders at all events, pre- and post-tests:

Person completing form: __________________________

Date: _____________

City Name: ___________________

Event Name: _________________

| Participant Names and ID (if applicable) | Contact Information (Primary Phone and E-mail) |

| Participants who did not attend event: | Contacted? (Y/N) | If dropping out of program, reason for dropping out? |

3. Fidelity of the Program:

Intervention city coordinators and event leaders will fill out the following form, to be compared with that of other cities to ensure uniform program implementation. This form will be completed at pre-test, and post-tests at 3 months and 6 months.

Instructions: please indicate how well you believe each item was implemented on a scale of 1 through 5 by marking the appropriate column (1= poor, 3= fair, 5= excellent).

| Item | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Were pamphlets/flyers regularly passed out and made available to individuals? | |||||

| Were scheduled seminars completed? | |||||

| What was the average level of participant engagement at seminars? | |||||

| How would you rate average participation at events? | |||||

| Were the appropriate materials presented at events? | |||||

| Was the website running properly? | |||||

| Were e-mails responded to promptly? | |||||

| Were e-mail and letter folic acid reminders sent out regularly and on-time? | |||||

| Were Q/A sessions at pop-up tents completed? | |||||

| Were discussions about folic acid and neural tube defects completed in a healthcare setting? |

Instructions: Please mark the appropriate column pertaining to each item implemented in the program.

| Item | Yes | No |

| Were radio and television advertisements broadcasted once per day? | ||

| Was at least one billboard posted in a municipal area? | ||

| Were there any technical difficulties at events? | ||

| Were there at least 15 posters posted around town? |

References

Chen, M.-Y., Rose, C. E., Qi, Y. P., Williams, J. L., Yeung, L. F., Berry, R. J., … Crider, K. S. (2019). Defining the plasma folate concentration associated with the red blood cell folate concentration threshold for optimal neural tube defects prevention: a population-based, randomized trial of folic acid supplementation. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 109(5), 1452–1461.

Felkner, M., Suarez, L., Hendricks, K., & Larsen, R. (2005). Implementation and outcomes of recommended folic acid supplementation in Mexican-American women with prior neural tube defect-affected pregnancies. Preventive Medicine, 40(6), 867–871.

Fellow, S. C. R., Lecturer, D. M., Professor, J. V. W., Professor, M. R. S. A., Medicine, R. M. C. in P. H., Professor, A. M. M., & Professor, M. J. T. (2018). Optimization of folic acid supplementation in the prevention of neural tube defects. Journal of Public Health, 40(4), 827–834.

Nawapun, K., & Phupong, V. (2007). Awareness of the benefits of folic acid and prevalence of the use of folic acid supplements to prevent neural tube defects among Thai women. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, (1), 53.

van der Pal-de Bruin, K. M., de Walle, H. E. K., de Rover, C. M., Jeeninga, W., Cornel, M. C., de Jong-van den Berg, L. T. W., … Paulussen, T. G. W. M. (2003). Influence of educational level on determinants of folic acid use. PAEDIATRIC AND PERINATAL EPIDEMIOLOGY, (3), 256.

Turgul, O., Anli, N., Mandiracioglu, A., Bati, H., & Akkol, S. (2009). The regional campaign for women on awareness of neural tube defects and folic acid in Narlidere, Izmir: a community-based intervention. European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care, 14(1), 69.