Part I. Community Guide Update and Rationale for Intervention

| Author & Year | Intervention Setting, Description, and Comparison Group(s) | Study Population Description and Sample Size | Effect Measure (Variables) | Results including Test Statistics and Significance | Follow-up Time |

| Izumi, et al., 2015 | The Walk Your Heart to Health intervention was hosted by community and faith-based organizations in Detroit, Michigan. It was a 32 week long intervention and facilitated by Community Health Promoters who used evidence-based strategies to facilitate group cohesion and promote physical activity and participation in walking groups that met three times a week for 90 minutes per session. Participants were placed in one of two groups: intervention or lagged intervention where group leaders remained highly involved in leadership for a longer period of time (control group). | The study included 603 non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic white, and Hispanic participants across five cohorts that began the 32-week intervention between March 2009 and October 2011. | Participation in Walking group as measured by attendance. | Participation in the walking group increased the level of social cohesion by 1.53 points. This effect is significant, with a p value of less than 0.001 and indicates that for those who participated in the walking group, their sense of social cohesion increased. | Follow-up at 4, 8, and 32 weeks. |

| Mouton & Clous, 2015 | This intervention studied the efficacy of social support and environment centered interventions and web-based interventions at promoting physical activity in older adults. Eligible participants were randomized into four groups: web-based, center-based, mixed combination, and a final control group. | There were 149 participants, over the age of 50 years old. The mean age was 65 years old with a standard deviation of 6. | The analyses included self-reported physical activity level, stage of change for physical activity, and awareness about physical activity. | Of the three types of interventions, Center-based, Web-based, and mixed, the most effective in increasing physical activity was the mixed intervention, with an average increase of 238 MET (metabolic equivalent of task) minutes per week, with a significant effect (P value 0.041). This shows that education/resources coupled with social support was effective in increasing physical activity. | This was a three month intervention, with follow-up at the 6 month and 12 month markers. |

| Adams et al., 2015 | This intervention was a community-based walking intervention at a church in a southeastern state in order to promote physical activity among African American women ages 35 to 69. Five weekly group sessions were offered to participants to encourage support and continued participation. | There were 25 voluntary participants between the ages of 38 and 68 years old. They classified themselves as not meeting physical activity recommendations of 150 minutes of moderate or vigorous intensity per week. | Results were measured in time spent in minutes doing vigorous physical activities, moderate physical activities, walking, and sitting. | The mean sitting time decreased by 111.17 minutes per week. The mean time spent in moderate physical activity rose by 5.73 minutes per week. There was a decrease in the number of participants who reported not walking from 5 participants pre-intervention to 2. The significance was not noted in the article. | Follow-up was given at 6 weeks; one week after the 5-week intervention ended. |

The Community Guide (2002) currently recommends implementing community social support efforts to increase physical activity. This recommendation is based off of a review of nine studies in which social support interventions in community settings were effective in increasing physical activity, as measured by various indicators including frequency of attending exercise sessions, flights of stairs climbed and minutes spent in physical activity. Among the nine interventions reviewed, there was a median increase in time spent being physically active of 44.2%. The frequency of physical activity also had an increase of 19.6%. Furthermore, one study found that participants who received social support more frequently were more active than those who received less frequent social support.

After reviewing three recent studies, it is still recommended that social support interventions are used in community settings to increase physical activity among participants. Consistent with the prior review of interventions, this review suggests that social support is an effective intervention in improving the amount of physical activity among participants. Each of the three interventions chosen show that increased social support increases physical activity among participants in community-level interventions. For example, in the Mouton and Clous (2015) intervention, center-based intervention led to a lower dropout level in the intervention. The intensity of the center-based intervention in contrast with web-based intervention showed that social support increased physical activity. There was also a higher perceived satisfaction in the center-based intervention in comparison to web-based intervention (Mouton and Clous, 2015). Social cohesion was also significantly associated with consistent participation in a walking group in the Walk Your Heart to Health Intervention (Izumi et al., 2015). Finally, in a community-based walking group at a church, time spent sitting decreased, minutes in moderate physical activity increased, and the number of participants who reported not walking decreased from 5 to 2. These interventions, combined with the success of the nine previous social interventions in community settings suggest that this type of intervention is an appropriate approach to increase physical activity in communities.

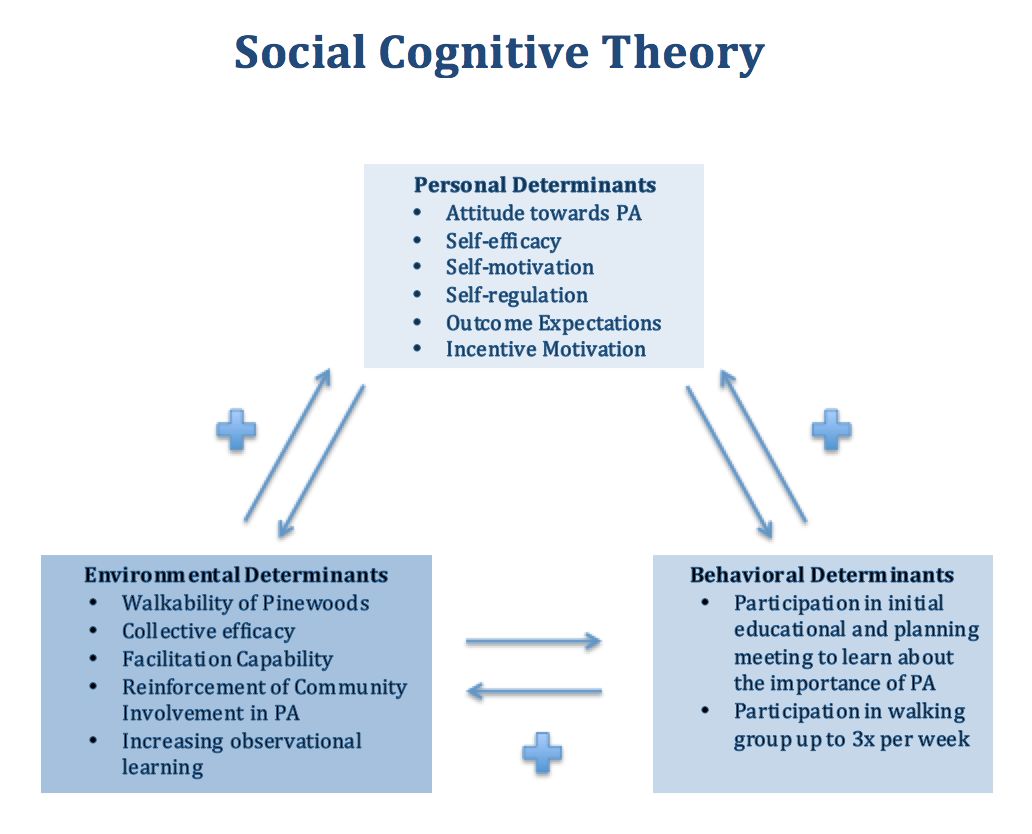

Part II. Theoretical Framework/Model

Social Cognitive Theory is a model that demonstrates the interaction between personal factors, environmental factors and behavior (Glanz et al., 2002). The theory demonstrates that behavior is affected by (a) personal beliefs, values, self-efficacy, and other individual level factors (b) is the imitation of the behaviors of those around you and (c) the environment in which you live. This theory will help explain the role of each of these factors in implementing a successful Social Support Intervention to promote physical activity in the Pinewoods Community.

Outcome Expectations. Outcome expectations are beliefs about the value and likelihood of the consequences of behavioral choices (Glanz et al., 2002). The intervention will need to promote and demonstrate the positive outcomes of increasing physical activity to increase the likelihood of the desired participation in a walking group. Some positive outcomes of increasing physical activity as a lifestyle that will appeal to the women in the Pinewoods Community include decreasing risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes, lowering BMI, and improving mental health and mood.

Self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is the belief and confidence in one’s ability to perform a given behavior. It is task-specific and can increase or decrease based on the specific task (Glanz et al., 2002). The intervention of a walking group was chosen as an activity that most people can participate in, in comparison to a jogging or running group which may discourage participants who have a low self-efficacy in their ability to jog or run. In addition to choosing walking as an intervention, the walking will be broken down into small, measurable steps and will recognize the small successes throughout the intervention.

Collective efficacy. Collective efficacy is the belief and confidence in a group’s ability to bring about a specific desired change and the willingness of community members to intervene in order to help others. Because this intervention is a Community-level intervention, it will require participants to work towards a common goal of increasing walking in their community. The success of the intervention will also be inter-dependent upon the involvement of individuals and the collective whole. It will be most successful if participants encourage each other to participate and communicate with their peers when they are not participating in the walking group in order to encourage them to continue walking towards their goals.

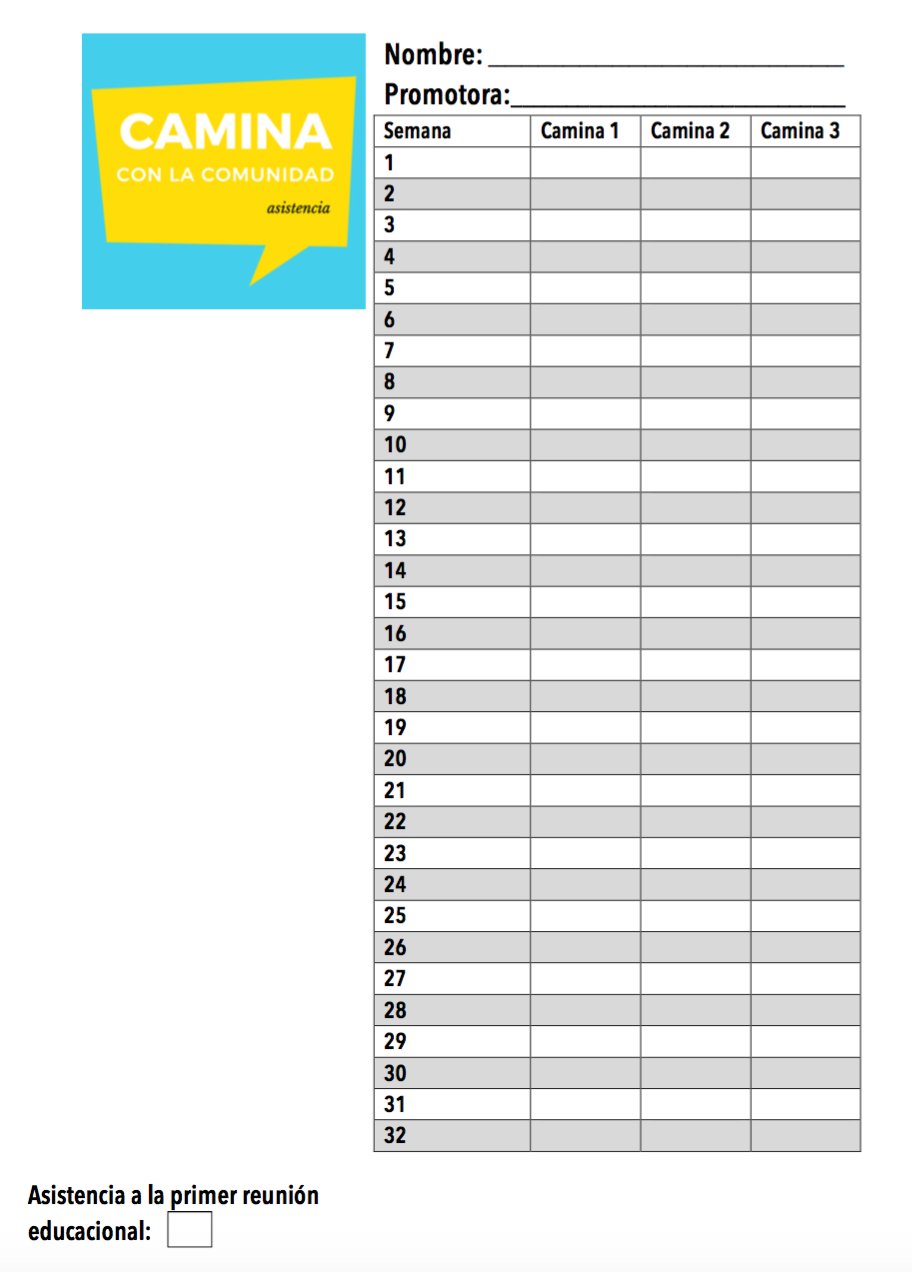

Self-Regulation. Self-regulation is controlling outcomes through self-monitoring, goal-setting, feedback, self-reward, self-instruction, and social support (Glanz et al., 2002). Although the group will serve as a support, individuals will also be responsible for their own reward systems and goal-setting. Participants will be provided a log in order to keep track of their weekly participation in the program. There will be a space allocated to log time for each of the three meetings held each week for the entirety of the 32-week intervention. In addition to scheduling their walking time with their group members, it will be necessary for participants to gain the support of their family members and friends to encourage and allow their participation in the walking group.

Facilitation/Behavioral Capability. Providing tools and resources, or environmental changes can increase facilitation and behavioral capability that make the new behavior easier to perform (Glanz et al., 2002). Signs that designate the walking path can create a greater sense of community support for the walking intervention. Also, selecting a time for the group during Oasis Tutoring services will assist mothers to participate

Observational Learning. Observational learning involves observing similar individuals or role models perform a new behavior (Glanz et al., 2002). This construct will be instrumental in encouraging mothers to participate in the walking group. It is predicted based on previous interventions, that when participants see their peers making time in their busy schedules to continue to participate in the intervention, they will be encouraged to do so as well. Also, because the walking path will weave throughout the Pinewoods Community, those who do not participate will still have visibility of the group activities, reminding and encouraging them to participate.

Incentive Motivation. Incentive motivation includes the use of rewards and punishments to modify behaviors (Glanz et al., 2002). Participants who notice a change in their mood, a decrease in stress levels, an increase in socialization, or weight loss will be motivated to continue their walking behavior.

The notion of reciprocal determinism is represented in the Social Cognitive Theory. As evidenced above, an increase in one determinant will positively increase other determinants. For example, an increase in the walkability of Pinewoods will increase participation in the walking group and increase self-motivation to walk. An increase in self-efficacy will increase participation in the walking group and increase collective efficacy as group members support each other and model positive physical activity behaviors.

Part III. Logic Model, Causal and Intervention Hypotheses, and Intervention Strategies

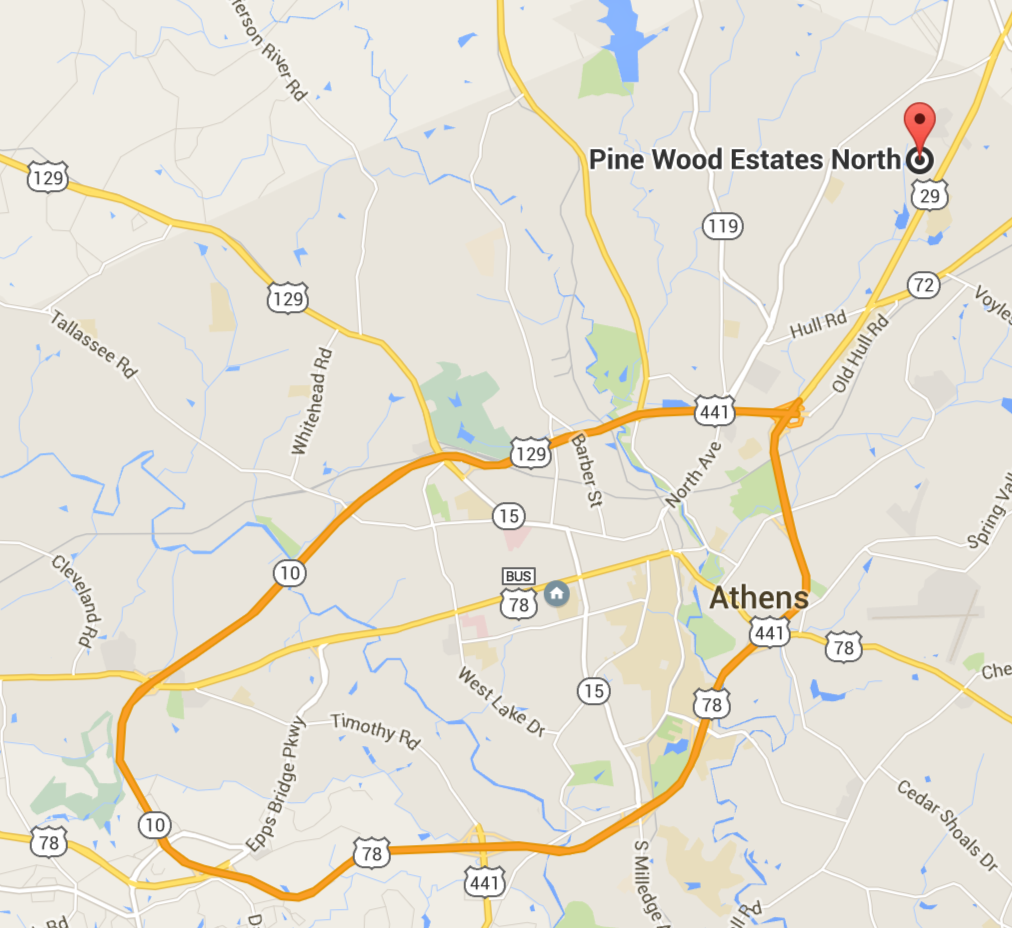

The target population of this walking intervention is Latina mothers and grandmothers of all ages in the Pinewoods community. This target population is considered a health disparate group due to their status as women, as well as the undocumented status of the majority of the Latina women in the community. According to the Office of Minority Health, low levels of physical activity are common among US-based Latinos (Albarran 2014). Additionally, immigration status is a risk factor for obesity due to low income-status of many immigrants, availability of healthy foods in low-income communities, and access to recreational facilities (Albarran 2014). These statistics relate to the women in the Pinewoods community who live in a low-resource area, located on the margins of Athens far from access to social services and opportunities for physical activity.

The intervention will take place inside the Pinewoods community, as transportation along with fear of deportation keep a majority of the community members from accessing services outside of their community. Pinewoods is a collection of mobile homes, connected in a web of gravel roads. Although the community does not have ideal walkability, with proper signage reminding drivers to drive slowly and watch for walkers, the roads could become more walkable through the implementation of this intervention.

| Intervention Method | Alignment with Theory | Intervention Strategy |

| Increase knowledge of the recommendations for weekly physical activity and the benefits of participating in a walking group. | The Social Cognitive Theory explains that Outcome Expectations are beliefs about the value and likelihood of the consequences of behavioral choices. If participants are able to understand that they need at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity each week to remain healthy, SCT suggests that knowledge of this impact on their physical health will have an effect on their participation in the intervention. Incentive Motivation is another construct of SCT that will affect participation. If participants understand that they could see an improvement in their mood, stress levels, or weight, they may be more likely to participate. | An initial Group Educational and Planning Session will be conducted to explain the 150 minute of moderate-intensity aerobic activity CDC recommendation, as well as positive effects of walking, including increased mood. |

| Develop time management, planning, and self-evaluate skills for participation. | The Social Cognitive theory explains the importance of Self-regulation. Participants will need to arrange their family schedules in order to find time to participate in the walking group. They will need to plan and communicate with their team members to arrange a time that will work for their team to meet to walk. They will also need to self-evaluate after each walking session to gauge how the intervention is affecting them. Behavioral Capability will also be encouraged through the development of time management skills and resources. | The Initial Group Educational and Planning Session will provide education and resources on time management, planning and evaluation skills, including suggestions of ways to arrange a family schedule in order to allot time for the walking groups. During this large group session, individual walking groups will be determined and a Promotora assigned to each group. Although attendance in the walking program will be logged by Promotoras, individual participants will be asked to rate how they felt after each walking session. They will be provided a chart for this log, and will note how they feel on a scale from one to ten both physically and mentally. |

| Increase Social Support | The Social Cognitive theory along with the interventions included in the Community Guide Review emphasize the importance of social support in increasing participation in physical activity. | After the initial group Educational and Planning Session, each Walking Group will be meet three times per week to walk, then fill out self-evaluation forms. The Walking Group will serve as a space to exercise together to promote group cohesion and social support. |

| Improve self-efficacy through observational learning and facilitation capability building. | The SCT suggests that participants will be reminded to increase their physical activity through observational learning. By seeing others who are similar in age, race, socio-economic status, or weight participate in the walking group, they may be encouraged to participate as well. SCT also suggests that their self-efficacy, or confidence in their ability to participate in the walking group, will be directly affected by seeing others like them participate. Also, Promotoras will help build self-efficacy among participants, helping them understand that they can take small steps toward improving their health. Facilitation capability building will occur to create a safer space for walking in the community; by providing environmental changes, participants may feel more comfortable, encouraged, and reminded to participate. | Although the group walking sessions will be the main strategy current walkers in the community to become “Promotoras” and provide individual peer support. Each participant will have a promotora who will remain in contact with them regarding their participation in the walking group. Signs will be posted throughout the community to remind drivers to be mindful of walkers, and reminding the whole community to get walking. |

Logic Model

| Inputs/Resources | Activities | Outputs | Short-term Outcomes | Intermediate Outcomes | Long-term Outcomes |

| The Community Guide and Promotoras research to guide intervention CDC recommendations for physical activity Grant to fund training for promotoras, promotoras pay, paper materials for the walking group, “Slow down for walkers” signs for the neighborhood, and promotional teaser post cards 5 Promotoras selected from Pinewoods as Walking Group Leaders Pinewoods community roads for walking paths | Training day for 5 Promotoras who will lead the Walking Groups An initial Group Educational and Planning Session will be conducted to explain the 150 minute of moderate-intensity aerobic activity CDC recommendation, as well as positive effects of walking. The Initial Group Educational and Planning Session will provide education and resources on time management, planning and evaluation skills, including suggestions of ways to arrange a family schedule in order to allot time for the walking groups. During this large group session, individual walking groups will be determined and a Promotora assigned to each group. Attendance in the walking program will be logged by individual participants and will be collected by Promotoras. The log will include a space to detail the actual minutes spent walking at eat of the three weekly sessions. After the initial group Educational and Planning Session, each Walking Group will be meet three times per week to walk, then fill out self-evaluation forms. The Walking Group will serve as a space to exercise together to promote group cohesion and social support. Although the group walking sessions will be the main strategy current walkers in the community to become “Promotoras” and provide individual peer support. Each participant will have a promotora who will remain in contact with them regarding their participation in the walking group. Signs will be posted throughout the community to remind drivers to be mindful of walkers; this will serve as a means of facilitating a more conducive space for walking. | 5 Promotoras will be trained to lead groups of 6 walkers each 30 Walker packets, consisting of walking log for the 32 week intervention and information on the benefits of walking to be presented on the first educational training day 30 Pinewoods women ages 15 and up will participate in initial training session and 32 weeks of intervention. Part-time employment for 5 promotoras. | Increase knowledge of the recommendations for weekly physical activity and the benefits of participating in a walking group. Develop time management, planning, and self-evaluation skills for participation. Increase Social Support Improve self-efficacy through observational learning and facilitation capability building. | Increase the number of women in Pinewoods who are demonstrating the recommended 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise (walking) recommended each week. Increasing awareness and knowledge of the importance of and accessibility to physical activity. | Long term health outcomes for increased participation in physical activity include: decreasing risk of cardiovascular disease decreasing risk of diabetes, lowering BMI improving mental health and mood |

Intervention Hypotheses

- Training day for 5 Promotoras who will lead the Walking Groups will increase knowledge of the recommendations for weekly physical activity and the benefits of participating in a walking group.

- Initial Group Educational and Planning Session will increase knowledge of the recommendations for weekly physical activity and the benefits of participating in a walking group and will allow participants to develop time management, planning, and self-evaluation skills for participation.

- Self-monitoring of the effects of the walking group on the provided logs will improve self-efficacy.

- Walking group meetings three times per week will increase social support.

- Promotoras will provide support to their group members to improve self-efficacy through observational learning and facilitation capability building.

- Posting signs throughout the community to remind drivers to be mindful of walkers, and reminding the whole community to get walking will increase knowledge of the recommendations for weekly physical activity and the benefits of participating in a walking group.

Causal Hypotheses

- Increasing knowledge of the recommendations for weekly physical activity and the benefits of participating in a walking group will increase the number of women in Pinewoods who are demonstrating the recommended 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise (walking) recommended each week.

- An increase in time management, planning, and self-evaluation skills for participation will increase the number of women in Pinewoods who are demonstrating the recommended 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise (walking) recommended each week.

- Increasing Social Support will increase the number of women in Pinewoods who are demonstrating the recommended 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise (walking) recommended each week.

- An increase in improved self-efficacy through observational learning and facilitation capability building will lead to an increase in the number of women in Pinewoods who are demonstrating the recommended 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise (walking) recommended each week.

Outcome Objectives

- Goal 1: Increase knowledge of the recommendations for weekly physical activity and the benefits of participating in a walking group.

- Outcome Objective 1.1: 90% of participants will accurately denote the recommended weekly physical activity on the post-test at the end of the 32 week intervention.

- Outcome Objective 1.2: 90% of participants will be able to list two benefits of participating in a walking group on the post-test at the end of the 32 week intervention.

- Goal 2: Develop time management, planning, and self-evaluation skills for participation.

- Outcome Objective 2.1: By week 8, the number of participants who report an increase in time management, planning and self-evaluation skills will be at least 50%.

- Outcome Objective 2.2: By week 16, the number of participants who report an increase in time management, planning and self-evaluation skills will be at least 60%.

- Outcome Objective 2.3: By week 32, the number of participants who report an increase in time management, planning and self-evaluation skills will be at least 80%

- Goal 3: Increase Social Support

- Outcome Objective 3.1: By week 8, the number of participants who report feeling socially supported by their walking group will be at least 50%.

- Outcome Objective 3.2: By week 16, the number of participants who report feeling socially supported by their walking group will be at least 60%.

- Outcome Objective 3.3: By week 32, the end of the intervention, the number of participants who report feeling socially supported by their walking group will be at least 80%

- Goal 4: Improve self-efficacy through observational learning and facilitation capability building.

- Outcome Objective 4.1: By week 8, the number of participants who report low feelings of self-efficacy will decrease by 25%.

- Outcome Objective 4.2: By week 16, the number of participants who report low feelings of self-efficacy will decrease by 50%.

- Outcome Objective 4.3: By week 32, 80% of program participants will report high feelings of self-efficacy.

Part IV. Evaluation Design and Measures

| Stakeholder | Role in Intervention | Evaluation Questions from Stakeholder | Effect on Stakeholder of a Successful Program | Effect on Stakeholder of an Unsuccessful Program |

| Participants | Walking group members and Promotora leaders | How will my participation in the walking program affect my physical health? How will my participation in the walking program affect my feelings of being part of this community? | Increase in knowledge of the importance of physical activity. Increase in physical health and feelings of social support. | No increase in physical activity. No increase in feelings of social support. |

| Family Members | Provide support to mothers/grandmothers/wives who are participating in the intervention | How will my family member’s participation in the program affect the family’s schedule? How will my family member’s participation in the program affect my family’s health? | Motivation to continue support family member’s involvement in physical activity. Knowledge of the effects of physical activity. | Resistance to allowing their family members to participate in similar activities in the future. Less support of physical activity interventions in the future. |

| Grant funders | Provide funding to supply signs for the community, walking logs and educational materials for participants. | Is the program worth the funding being invested? Is the money being invested being used as it was designated to be? | Participants in the program will be able to encourage others in the community to get active. Signs and visible participation in the intervention will increase community support and participation in physical activities. | Wasted resources and hesitancy to support again in the future. |

| Casa de Amistad, ALCES, & Oasis Catolico | As long-standing organizations that work in Pinewoods, these organizations will encourage community members to participate in the intervention. | Is this program worth the time that participants are investing in it? Are the leaders of this program trustworthy to protect the identity of participants. | Increased confidence in program and desire to promote similar programs to the Pinewoods community that they serve. | Unwillingness to refer clients to future similar programs. |

Outcome Evaluation Design: Group randomized control trial

The outcome evaluation will be a group randomized control trial. The group will be the 30 participants in the walking groups led by Promotoras and one control group consisting of 10 participants who are not in a walking group, but attend the Initial Group Educational and Planning Session which will provide education and resources on time management, planning and evaluation skills, including suggestions of ways to arrange a family schedule in order to allot time for the walking groups.

R O1 TX O2 O3 (Intervention group)

R O1 O2 O3 (Control Group)

[O1= pre-test at Initial Group Educational and Planning Session

O2= post-test 32 weeks O3= post-test after official walking groups conclude, 40 weeks]

All participants will come from the Pinewoods community, and there will be randomized assignment into either a walking group or individual walking plan. Pre-test will be administered at the Initial Group Educational and Planning Session. The tests will assess: participants knowledge of the recommendations for weekly physical activity (Goal 1), time management, planning, and self-evaluation skills (Goal 2), self-reported feelings of social support (Goal 3), and self-reported self-efficacy (Goal 4).

Threats to internal validity:

By using a group randomized control trial, participants should be randomly divided into groups regardless of their current knowledge and participation in physical activity. Despite these efforts to increase internal validity through randomization, threats to internal validity still exist. The two main threats to this study include testing bias and attrition. First, by asking both groups to attend the first meeting and take the pre-test, the control group will also be aware of the importance of social support, and may be encouraged to seek out their own walking partners outside of the program. Also, attrition could affect the post-test results, as the participants who remained in the program may be more motivated, and more knowledgable of the importance of physical activity.

Despite these threats, by using a pre-test in addition to the post-test, there will be increased internal validity. For example, the study will be able to follow participants who drop out of the program and account for any differences in their pre-test characteristics. The pre-test can also help demonstrate how similar or different the treatment groups are.

| Short-term or Intermediate Outcome Variable | Scale, Questionnaire, Assessment Method | Brief Description of Instrument | Example item (for surveys, scales, or questionnaires) | Reliability and/or Validity Description |

| Increase knowledge of the recommendations for weekly physical activity and the benefits of participating in a walking group. | Survey which asks about recommended duration, frequency, and intensity of physical activity (Marques et al., 2015) | The survey has three questions pertaining to the recommendations for physical activity. The three questions are regarding to frequency, duration, and intensity recommendations. The questions regarding frequency and duration had seven options to choose from, and the question regarding intensity had four options. Those who answered all three questions correctly were determined to have knowledge of the recommendation for physical activity. | How many days a week of physical activity are recommended for overall health benefits? Options ranged from 1 day to 7 days a week. | According to Marques et al., (2015) “There is no evidence to suggest that validity of the questionnaire differs by students’ knowledge of the physical activity recommendation.” (p. 256) |

| Develop time management, planning, and self-evaluation skills for participation. Increase Social Support. | Questionnaire based off of the health belief model and social support and self-regulation. (Jeihooni et al., 2016) | 23 questions on knowledge, 4 questions on the perceived susceptibility to osteoporosis, 8 questions on the perceived benefits of taking preventive measures (ex. physical activity), 7 questions on perceived barriers (including barriers to physical activity), 4 questions on motivation, 4 questions on self efficacy, 3 questions on internal cues to action, 16 questions on self-regulation (including setting goals and planning preventive behaviors of osteoporosis), and 9 questions on social support. | All questions except for those pertaining to social support were based on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The social support questions ranged from 1-4: very much, moderately, a little, and not at all. No sample questions were included in the study. | The overall reliability of the questionnaire based on Crobach’s alpha was 0.87. More specifically the reliability for each on Crobach’s alpha was: · knowledge: .86 · perceived susceptability: .71 · perceived severity: .82 · perceived benefits: .79 · perceived barriers: .82 · motivation: .77 · self-efficacy: .79 · cues to action: .77 · self-regulation: .73 · social support: .79 |

| Improve self-efficacy through observational learning and facilitation capability building. | SELPA, Self efficacy questionnaire regarding leisure time physical activity (Abasi et al., 2016) | This questionnaire included three main parts: (1) demographic characteristics of participants (2) physical activity measurements using the long version of international physical activity questionnaire (3) a 13 item questionnaire regarding self-efficacy, measuring the “degree of confidence of participants in their ability in overcoming barriers, goal setting, and implementation of programs about physical activity using a 5-point Likert scale”. | “I could prioritize physical activity when I create my personal schedule.” | The study determined that SELPA has acceptable construct validity. The highest correlation between self efficacy and physical activity was shown through the twelth item of the questionnaire with a correlation of .86. The lowest correlation was .52 and is associated with a lack of suitable place for PA. |

Part V. Process Evaluation and Data Collection Forms

Recruitment and enrollment – how will you track who you invite to participate in your intervention and who actually takes part?

Two months before the intervention begins, each of the households in Pinewoods will receive a “teaser” postcard, as pictured above, in their mailboxes at the entrance of Pinewoods. The back of the postcard will include sign up information that can be sent back to the program to express interest. One month before the intervention begins, the Principal Investigator along with representatives from ALCES and Casa de Amistad will have a booth with health information and promotion at the front of the neighborhood along with giveaways provided by the University of Georgia. This will be the main opportunity for sign-ups, with stakeholders present who can help give the women additional assurance of the validity of the program.

Attrition – Participation in each of the walking meetings will be personally recorded by participants, as to incorporate self-monitoring and organizational skills. Each week, the participants will log the number of minutes they walked at each group meeting (camina). This notation will allow for detailed data regarding the actual minutes of physical activity completed by each participant at each meeting. Promotoras will collect these forms from participants in the intervention group. They will be submitted to the Principal Investigator for participants in the control group.

Fidelity of the program –

The following survey will be completed after the Initial Group Educational and Planning Session.

The following surveys will occur at the end of the intervention at 32 weeks.

The following test will occur at the as a pre-test at the beginning of the Initial Group Educational and Planing Session before information is presented and at the end of the intervention at 32 weeks.

Sources

Abasi, M. H., Eslami, A. A., Rakhshani, F., & Shiri, M. (2016). A self-efficacy questionnaire regarding leisure time physical activity: Psychometric properties among Iranian male adolescents. Iranian Journal Of Nursing & Midwifery Research, 21(1), 20-28. doi:10.4103/1735-9066.174751

Adams, T., Burns, D., Forehand, J. W., & Spurlock, A. (2015). A Community-Based Walking Program to Promote Physical Activity Among African American Women. Nursing for Women’s Health, 19(1), 26-35. doi:10.1111/1751-486x.12173

Albarran, C. R., Heilemann, M. V., & Koniak-Griffin, D. (2014). Promotoras as facilitators of change: Latinas’ perspectives after participating in a lifestyle behaviour intervention program. Journal Of Advanced Nursing, 70(10), 2303-2313 11p. doi:10.1111/jan.12383

Glanz, K., Rimer, B. K., & Lewis, F. M. (2002). Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice (4th ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Izumi, B. T., Schulz, A. J., Mentz, G., Israel, B. A., Sand, S. L., Reyes, A. G., … Diaz, G. (2015). Leader behaviors, group cohesion, and participation in a walking group program. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 49(1), 41–49. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.01.019

Marques, A., Martins, J., Sarmento, H., Rocha, L., & Carreiro da Costa, F. (2015). Do Students Know the Physical Activity Recommendations for Health Promotion?. Journal Of Physical Activity & Health, 12(2), 253-256.

Jeihooni, A. K., Hidarnia, A., Kaveh, M. H., Hajizadeh, E., & Askari, A. (2016). Application of the health belief model and social cognitive theory for osteoporosis preventive nutritional behaviors in a sample of Iranian women.Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research, 21(2), 131–141. http://doi.org.proxy-remote.galib.uga.edu/10.4103/1735-9066.178231

Mouton, A., & Cloes, M. (2015). Efficacy of a web-based, center-based or combined physical activity intervention among older adults. Health education research, 30(3), 422-435.