*All edits have been bolded

| Author & Year | Intervention Setting, Description, and Comparison Groups | Study Population Description & Sample Size | Effect Measure (Variables) | Results, including Test Statistics & Significance | Follow-up Time |

| Huys, et al., 2019 | The “Taste Garden” was a 9-week school garden program that evaluated the effects of gardening and educational lessons in primary schools. The researchers measured 8 indicators of the intervention outcomes through evaluation questionnaires given to students. A total of 350 children filled out questionnaires on vegetable consumption, determinants and process of the program. 149 children from 5 schools were the intervention group, 201 children from 8 schools served as controls. | 350 school children (149 intervention group, 201 control). | vegetable consumption, soup consumption, awareness, social norm, parental influence, knowledge, self-efficacy, and attitude. | Intervention effect was only found for knowledge (p=0.02), with a very small effect size (0.55%). Small effects were found for awareness (p between 0.005 and 0.007 and an effect size of 0.63%) and knowledge (p between 0.04 and 0.09 and effect size 0.65%). “Taste Garden” . showed no effects on vegetable consumption and small effects on its determinants. | No long-term follow-up. |

| Leuven, et al., 2018 | An intervention period of 7 months (17 lessons) was organized for primary school students in the Netherlands. Surveys were conducted before and after the intervention period to test the ability of students to identify vegetables, measure their self-reported preference of vegetables, and to analyze students’ attitudes toward statements about gardening, cooking, and outdoor activity. Results were compared with a control group of 65 students. | 150 primary school students age 10–12 in the Netherlands. | Ability of students to identify vegetables, to measure their self-reported preference for vegetables, students’ attitudes towards statements about gardening, cooking, and outdoor activity. | School gardening was found to significantly increase the knowledge of primary school-children on 10 vegetables as well as their ability to self-report preference for the vegetables. Short-term (n=106) and long term (n=52) preference for vegetables increased (p<0.05) in comparison with the control group. Control group did not show a significant learning effect (p>0.05). This implies that the exposure to vegetables from school gardening programs may increase willingness to taste and daily intake of vegetables in the long term. Students’ attitudes toward gardening, cooking, and outdoor activity were unaffected. | Long-term effects were measured by repeating the survey 1 year after the intervention. (n=52). |

| Landry, et al., 2019 | This study assessed the association between changes in cooking and gardening behaviors with changes in dietary intake and obesity in participants of the LA Sprouts study, an after-school, 12-week, randomized controlled cooking and gardening intervention conducted in four inner-city elementary schools in Los Angeles. | 290 low-income, primarily Hispanic/Latino 3rd-5th grade students who were randomized to either the LA Sprouts intervention (n = 160) or control group (n = 130). 49% male, 87% Hispanic/Latino, and an average age of 9. | Cooking and gardening psychosocial behaviors (attitudes, self-efficacy, motivation), dietary intake, obesity parameters (height, weight, waist circumference). | Increases in cooking behaviors significantly predicted increases in dietary fiber intake ( p = 0.004) and increases in vegetable intake ( p = 0.03). Increases in gardening behaviors significantly predicted increased intake of dietary fiber ( p = 0.02). Changes in cooking and gardening behaviors were not associated with changes in BMI z-score or waist circumference | Within 7-14 days of instruction ending |

I recommend that gardening interventions be used in primary schools to increase vegetable consumption and/or improve diet in children.

I agree with the Community Guide’s recommendation that gardening interventions increase vegetable intake among children. The Community Guide’s recommendation is based on sufficient evidence from a systematic review of 14 studies that examined gardening interventions conducted with children ages 2 to 18 years from 2005 to 2015.

Of the studies I have found since the Community Guide’s review, two of the three found significant improvements in knowledge about food and dietary choices. Leuven et al. found that school gardening significantly increased knowledge on 10 vegetables and improved self-reported preference for the vegetables. The exposure to vegetables generated by school gardening programs increased the willingness to taste and daily intake of vegetables in the long term. Landry et al. found similar results. The study found that increases in gardening behaviors significantly predicted increased intake of dietary fiber. The results of these studies are the reason I recommend gardening interventions to increase vegetable consumption among school-age children.

The Huys study, however, found conflicting results. This study concluded that a 9-week school gardening program showed no effects on vegetable consumption. There is no guarantee that the intervention will work in all contexts, but in general, it is safe to say that gardening improves food knowledge and choices among children due to the majority of evidence leading to that conclusion. For this reason, I “recommend” the intervention, but do not “strongly recommend” it.

References:

Huys, N., Cardon, G., Craemer, M. D., Hermans, N., Renard, S., Roesbeke, M., . . . Deforche, B. (2019). Effect and process evaluation of a real-world school garden program on vegetable consumption and its determinants in primary schoolchildren. Plos One,14(3). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0214320

Landry, M. J., Markowitz, A. K., Asigbee, F. M., Gatto, N. M., Spruijt-Metz, D., & Davis, J. N. (2019). Cooking and Gardening Behaviors and Improvements in Dietary Intake in Hispanic/Latino Youth. Childhood Obesity,15(4), 262-270. doi:10.1089/chi.2018.0110

Leuven, J. R., Rutenfrans, A. H., Dolfing, A. G., & Leuven, R. S. (2018). School gardening increases knowledge of primary school children on edible plants and preference for vegetables. Food Science & Nutrition,6(7), 1960-1967. doi:10.1002/fsn3.758

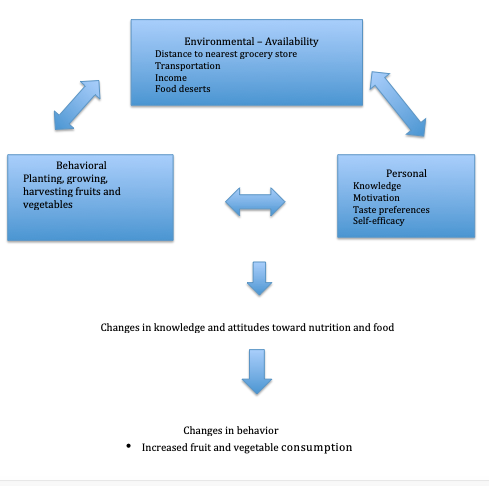

Part II. Theoretical Framework/Model

Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) is a model that emphasizes the ever-changing interaction between people, their behavior, and their environments. There is an emphasis on social influence and its impact on internal and external social reinforcement. SCT takes into account the unique way in which individuals begin and continue with a behavior, while also considering the social environment in which individuals act (“Health Behavior and Health Education,” n.d.). I chose this theory because I think it is especially important that environment is included in the theoretical model for vegetable consumption because many environmental factors influence diet. Social determinants of health such as income and accessibility to fresh food can have a significant impact on what children eat, and SCT includes the environmental aspect that other models leave out.

Constructs:

- Reciprocal determinism: This is the key concept of SCT. It refers to the dynamic and reciprocal interaction of a person (who has a set of learned experiences) with the environment (external social context) and behavior. A change in one component will produce changes in the others. For example, more positive thoughts on vegetable consumption (personal) can result in the behavior of eating more vegetables (behavioral), and social support (environment) for vegetable consumption can also result in that behavior.

- Behavioral Capability – This refers to a person’s actual ability to perform a behavior using the necessary knowledge and skills. Hands-on experience planting, growing, and harvesting fruits and vegetables along with a nutritional education will allow for children to make more educated, informed choices about their eating habits and increase fruit and vegetable consumption.

- Observational Learning – This refers to behavior acquisition through observing the actions and outcomes of others. Watching teachers and peers garden and make healthier food choices influences the individual to undertake similar behaviors.

- Reinforcements – This refers to the internal and external responses to a behavior that impact the likelihood of the individual continuing or terminating that behavior. Children who choose to eat more fruits and vegetables may have more energy, better focus, etc., and want to continue to make healthier choices.

- Expectations – This refers to the expected consequences of a behavior. Children may expect to feel better, eat tastier foods, or receive praise from adults for eating healthy.

- Self-efficacy – This refers to the level of a person’s confidence in their ability to undertake a certain behavior. Self-efficacy is influenced by observing peers and teachers, performance, and physiological states. Nutritional programs in class will equip students with the knowledge to make healthier choices, while gardening will help students form a hands-on connection to the food they eat.

(“Health Behavior and Health Education,” n.d.)

Theoretical Model

References:

Health Behavior and Health Education. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.med.upenn.edu/hbhe4/part3-ch8-key-constructs.shtml

In the U.S., the percentage of obese children and adolescents has more than tripled since the 1970s (Fryar, 2014). Obesity puts children at risk of heart disease, type 2 diabetes, asthma, sleep apnea, social discrimination, and many other physically, mentally, and emotionally harmful conditions (“Childhood Obesity Causes & Consequences,” n.d.). That is why my target population is children and the gardening and nutrition intervention will take place in primary schools.

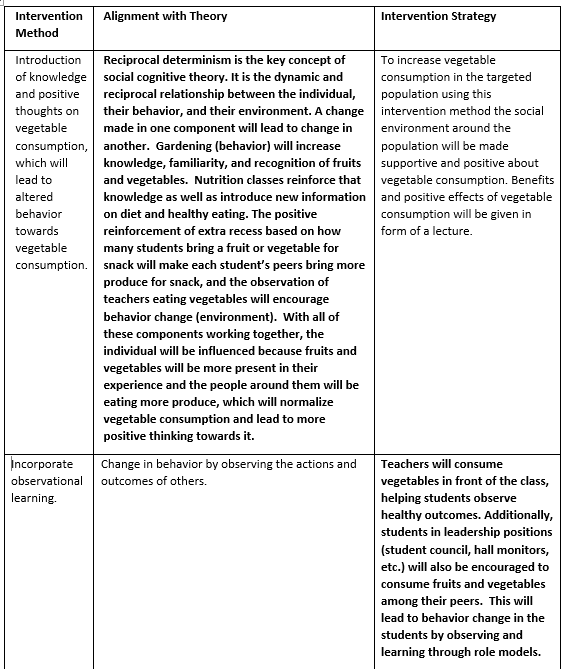

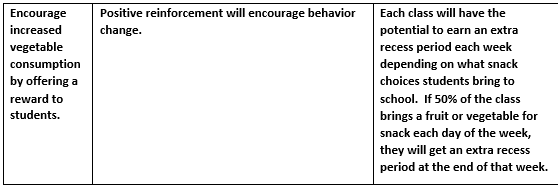

Part III. Logic Model, Causal and Intervention Hypotheses, and Intervention Strategies

Logic Model:

| Inputs | Activities | Outputs | Short-term outcomes | Intermediate Outcomes | Long Term Outcomes |

| Money required for the intervention (From the school) Open environment/ Garden (Location) Knowledge and Expertise for nutritional education Gardening supplies (resources) Time | 12-week gardening program where teachers and children will be planting, growing, and consuming vegetables and fruits in an activity format. 12-week lecture on nutrition coinciding with gardening program, which will give importance of vegetable consumption by talking about its benefits and positive effects. Provide positive reinforcements through a potential extra recess period each week. This will be specific to each class. During snack time each day, if a child brings and eats a fruit or vegetable as their snack rather than a packaged food, they receive a “point.” If points for the day add up to half the class size for the entire week, the class will be rewarded with an extra recess period at the end of that week. Facilitate observational learning by encouraging teachers and students in leadership positions to eat fruits and vegetables among students. | All teachers at each school will be trained to lecture on nutrition through a one-hour seminar before the start of the program. Nutrition lectures will take place once a week for 30 minutes for 12-week duration of the program. All teachers will also be encouraged to consume fruit and vegetables in front of children. Half of all teachers should consume a fruit or vegetable in front of students each day. Students will participate in a 1-hour gardening session once a week for the 12-week duration of the program. | Raised awareness about nutrition and vegetable consumption. Improved identification of vegetables and fruits. Better determination to consume vegetables. Improved knowledge towards choices about eating options. | Increased vegetable and fruit consumption. Behavioral change towards healthier options over unhealthy. Students consuming vegetables and fruits along with teachers and peers. | Reduction in childhood obesity. Improvement in lifestyle of children making it healthier. Reduction in other health problems due to obesity. |

Intervention Hypothesis- Gardening intervention along with nutritional education will lead to increased vegetable consumption in children.

Causal Hypothesis – Improved knowledge and experience towards nutrition will increase vegetable consumption and reduce childhood obesity and obesity-related health risks.

Gardening and nutrition lectures will increase knowledge of fruits and vegetables, increase awareness and highlight the importance of nutrition. Teachers will act as examples when they consume fresh produce in front of the children. Children will then learn from their environment and the behavior of others around them. This will initiate positive attitudes and thoughts about produce and healthy eating, which will in turn lead to increased consumption of nutritious foods, and subsequently lower rates of childhood obesity and risk of obesity-related health issues.

The goal of SCT is to explain how people regulate their behavior through control and reinforcement to achieve a behavior that can be maintained over time. A hands-on gardening component makes kids more familiar and comfortable with fruits and vegetables, increases the likelihood that they will eat them. Empowering children with the knowledge of why a healthy diet is important and how to eat healthy will give them some control and increase self efficacy, which can lead to changes in eating habits long-term. Having this knowledge and skills will increase behavioral capability. Teachers will model the desired behavior by consuming fruits and vegetables with and in front of the children. When the kids are able to see successful demonstration of healthy eating behavior, they can also engage in that behavior successfully. Positive reinforcement of an extra recess period increases the likelihood that students will increase fruit and vegetable consumption. Because the reinforcement is based on half the class bringing a healthy snack every day, students will not only want to bring healthy snacks for themselves, but will also encourage their peers to do the same so everyone can be rewarded. Positive attitudes, better acquaintance and knowledge on diet, fruits, and vegetables, along with positive reinforcements and observational learning by teachers modeling the desired behavior will lead to improved behavior in food choices in the long-term. A long-term healthy diet will lead to decreased rates of obesity, and in turn reduced risk for hypertension, heart disease, type 2 diabetes, depression and anxiety, and other weight-related conditions (“Health Risks of Being Overweight,” n.d.).

SMART outcome objectives

Goal 1: Improved knowledge towards choices about eating options.

- Objective: By the end of the 12 weeks, improvement in knowledge in all students from baseline by 30% on nutrition assessment surveys.

Goal 2: Increase consumption of fruits and vegetables in children.

- Objective: Increase weekly vegetable and fruit consumption by 2 servings per week among children eating below 4 servings of combined fruits and vegetables per day based on follow-up survey assessment.

Goal 3: Improved identification of vegetables and fruits.

Objective: Be able to identify 7/10 vegetables on follow-up nutrition assessment survey.

Goal 4: Better determination to consume vegetables.

- Objective: Students’ desire and willingness to consume fruits and vegetables increases by 15% based on follow-up survey.

Goal 5: Better determination to consume vegetables

Objective: Self-efficacy scores on follow-up assessment improve in all participants below 50% by 20%.

References:

Fryar CD, Carroll MD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among children and adolescents: United States, 1963-1965 through 2011-2012. Health E-Stats. 2014. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/obesity_child_11_12/obesity_child_11_12.htm. Accessed May 20, 2019.

Childhood Obesity Causes & Consequences | Overweight & Obesity | CDC. (n.d.). Retrieved May 23, 2019, from https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/childhood/causes.html

Health Risks of Being Overweight. (2015, February 01). Retrieved May 24, 2019, from https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/weight-management/health-risks-overweight

Part IV. Evaluation Design and Measures

| Stakeholder | Role in Intervention | Evaluation Questions from Stakeholder | Effect on Stakeholder of a Successful Program | Effect on Stakeholder of an Unsuccessful Program |

| Primary school students | Program participants served by the program. | How will this affect my health and eating habits? Will the program be fun? What do I want from this program? Will it be difficult or inconvenient? | Increase in consumption of fruits and vegetables. Increase awareness fruits and vegetables. Increase in knowledge about nutrition. Less obesity and obesity-related health outcomes. | No increase in fruit and vegetable consumption. No decrease in incidence of obesity and obesity-related health outcomes. |

| Parents of participants | Need permission from and support for children to participate | Is this best for my child? Is it safe? Is it fun? How will it affect my child’s health? | Child is healthier. Weight loss in overweight/obese children, weight maintenance for children at a healthy weight. Less health problems such as asthma, ADD/ADHD | No change in their child’s health. |

| Teacher, student leaders | Needed to model eating behaviors to students and educate on nutrition | Will the program be easy to implement? What kind of and how much nutrition training will be provided? Will I be able to model proper behavior and eat vegetables and fruits myself? Will I be judged by other students? | Increased knowledge and awareness of nutrition. Better health, weight loss. | No change in knowledge, weight, or health outcomes. |

| Program coordinators | Train teachers on nutrition. Show teachers and student leaders how to model desired behavior. | What are the expected results of the program? Will implementation be effective? | Ability to continue to implement and improve program. Increase program funding and participation | Evaluate program flaws in order to implement successfully in the future. |

Evaluation Design: Randomized Controlled Trial

In this design, students will be randomly assigned to a group that receives nutrition education, gardening, and incentives, or to a group that does not receive nutrition education, gardening, or incentives. Both groups will be tested twice, at the same times. This will be on the first day of the intervention and again on the last day of intervention. The tests will evaluate dietary behavior, nutritional knowledge, fruit and vegetable recognition, and perceived self efficacy. Pretest scores for both groups should have a similar distribution so that we know the two groups started in the same place. If the intervention was effective, the distribution of the post test scores from the group that received tutoring should be higher than the post test scores from the control group.

Randomization will be done by randomizing schools in order to eliminate the chance of contamination from the intervention group to the comparison group among individual students within schools.

R O1 X O2 (Intervention Group)

R O1 O2 (Control Group)

*O1 = pre-test at day 1, O2 = post-test at 12 weeks

Threats to internal validity:

Testing: Since this study design uses pre and post tests, testing bias is a threat to the internal validity of this study. By taking a pre-test, students might think about the issues in a way that they wouldn’t have done without the pre-test, which could affect their performance on the post-test. Thus, the change in outcomes seen from pre-test to post-test could be due to the difference in the way the pre-test affected each group, rather than being attributable to the program. Having a control group minimizes this threat because both groups will be exposed to the same pre-test.

Differential Attrition: This is a threat to any study design with more than one group. If more participants drop out of one group than another, then any changes from pre to post test may be attributable to the participants who dropped out or stayed in the program, and not the program itself. Having the study take place in schools will mitigate this threat because participants’ contact information will be available. Additionally, it is part of the regular school day so a participant moving or dropping out of school is the only way they could drop out of the study. Both of these are minimal during the school year.

| Short-term or Intermediate Outcome Variable | Scale, Questionnaire, Assessment | Brief Description of Instrument | Example item (for surveys, scales, or questionnaires) | Reliability and/or Validity Description |

| Increase nutritional knowledge | 5 a Day for Better Health initiative Child Psychosocial Questionnaire (Reynolds et al. 1999) | 10 true-false and multiple choice items that measure the knowledge needed to enact the behavior of fruit and vegetable consumption. This will measure improved knowledge towards choices about eating options. | Grilled foods are healthier than fried foods. (T/F) | Two-week test-retest reliability from pilot testing of the measures indi- cated a reliability coefficient of .48 for knowledge. |

| Increased consumption of fruits and vegetables | Healthy eating and physical activity behavior recall questionnaire for children ( HEPABRQ‐C) (Lassetteret al. 2018) | 10 items, two of which are in an open‐response format allowing children to write the actual foods they ate. The other eight items include two yes/no items, and the remaining six items had response options that were presented using an ordinal scale. This will measure the change in vegetable and fruit consumption and awareness about nutrition and vegetable consumption. | The last time I ate a snack at a friend’s house, I ate __________. Yesterday I ate ____ servings of fruit (0,1,2,3 or more) | CVI ranged from 0.88 to 1.00 |

| ImproveFV identification and taste preferences | Vegetable preferences ‘taste and rate’ method (Morgan et al., 2010) | Children were first asked to identify each of six raw vegetables (carrot, pea, tomato, broccoli, capsicum, lettuce) in their whole form and an assessment was made of their willingness to taste and their preference for each. Children who tasted a vegetable were asked what they thought of it and to indicate their preference using a facial hedonic scale and instructed to place a finger on one of the five face pictures enlarged to fit on one page and explained to the child before tasting: I really liked it a lot!; I liked it a little; It was OK; I did not like it; I really did not like it! The vegetables were presented in the following order: carrot, pea, tomato, broccoli, capsicum and lettuce. For the identification and willingness to taste section, students received 1 point for a correct or positive response with a total of 6 points possible. For the tasting preference, students could score a maximum of 5 points per vegetable, giving a total of 30 possible points. | What is the name of this food? Will you taste this food? | Outcome expectancies (Cronbach’s alpha = .60). Two-week test-retest reliability from pilot testing of the measures indicated a reliability coefficient of .47 for outcome expectancies |

| Improved self-efficacy | Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Self‐Efficacy Questionnaire for Children (HEPASEQ‐C) (Lassetteret al. 2018) | 9 items with response options on a 3‐point Likert‐type scale (1 = There is no way I can do this, 2 = This could be hard for me, 3 = I believe I can do this). Seven items focus on self‐efficacy related to healthy eating. This will measure students’ determination to consume vegetables. | I will eat healthy food even when my friends eat food that is not healthy. | CVI ranged from 0.80 to 1.00. Internal reliability: value of .749 |

References:

Lassetter, J., I. Macintosh, C., Williams, M., Driessnack, M., Ray, G., & Wisco, J. (2018). Psychometric testing of the healthy eating and physical activity self-efficacy questionnaire and the healthy eating and physical activity behavior recall questionnaire for children. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing(Vol. 23). https://doi.org/10.1111/jspn.12207

Morgan, P. J., Warren, J. M., Lubans, D. R., Saunders, K. L., Quick, G. I., & Collins, C. E. (2010). The impact of nutrition education with and without a school garden on knowledge, vegetable intake and preferences and quality of school life among primary-school students. Public Health Nutrition,13(11), 1931-1940. doi:10.1017/s1368980010000959

Reynolds, K. D., Hinton, A. W., Shewchuk, R. M., & Hickey, C. A. (1999). Social Cognitive Model of Fruit and Vegetable Consumption in Elementary School Children. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

Part V. Process Evaluation and Data Collection Form

Recruitment and enrollment:

Schools recruitment: schools will receive letters explaining the program

and request for participation

Gardening Interventions to Increase Vegetable Consumption in Children

School Recruitment Letter

Dear ______,

The University of Georgia School of Public Health in partnership with its Health Promotion students would like to invite you to be part of a gardening and nutrition program aimed at reducing rates of childhood obesity and adverse health outcomes in primary school-aged children. This 12-week program will feature a hands-on gardening component as well as weekly nutritional education seminars in order to raise awareness about nutrition and vegetable consumption, increase familiarity with fruits and vegetables, increase determination to consume vegetables, and improve knowledge on healthy eating. This intervention program targets primary school-aged children. If you are interested in participating in being part of this study and would like to learn more details about the program, please join us on August 1, 2019 at 7pm at the University of Georgia Health Sciences Campus to learn more.

Please contact us at healthykids@uga.edu or call 706-VEGGIES for more information.

Sincerely,

Healthy Kids Coordinator

University of Georgia School of Public Health

School Enrollment Form

| School Name | School Contact | Contact Phone Number | Total Number of Students |

Participant Enrollment Form – Students

| Student Name | Student’s School | Personal Phone Number | Personal Email | Enrolled? (Y/N) |

Attrition: Each student will be given a contact information form to fill out on the first day of the program.

Contact Information Form:

Name:

School:

Phone:

Email:

Home Address:

Parent/Guardian Name:

Do you plan to move or change schools in the next 12 weeks for the duration of the program?

Attendance will be taken each week for both the gardening session and nutrition lecture session.

| Student Name | Week 1 Gardening | Week 1 Nutrition | Week 2 Gardening | Week 2 Nutrition | Week 3 Gardening | Week 3 Nutrition | Week 4 Gardening | Week 4 Nutrition | Week 5 Gardening | Week 5 Nutrition | Week 6 Gardening | Week 6 Nutrition | Week 7 Gardening | Week 7 Nutrition | Week 8 Gardening | Week 8 Nutrition | Week 9 Gardening | Week 9 Nutrition | Week 10 Gardening | Week 10 Nutrition | Week 11 Gardening | Week 11 Nutrition | Week 12 Gardening | Week 12 Nutrition |

Fidelity: The program leader at each school will be given a fidelity form to fill out at the end of the program, which will consist of the following questions:

- Were all gardening sessions completed?

- Were all nutrition lectures completed?

- Did the teacher lead interactive discussions during nutrition lectures?

- Were different types of fruits and vegetables reviewed and identified?

- Did the teacher disseminate basic nutrition facts to help kids make healthier choices?

- Were students engaged during gardening and nutrition sessions?

- Did teachers and student leaders successfully demonstrate healthy eating behaviors?

- How often did teachers and student leaders eat fruits and vegetables in front of participants?

- Did participants regard teachers and student leaders as influential people?