Part I. Community Guide Update and Rationale for Intervention

| Author & Year | Intervention Setting, Description, and Comparison Group(s) | Study Population Description and Sample Size | Effect Measure (Variables) | Results, including Test Statistics and Significance | Follow-up Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Markham, et al., 2017 | Intervention Mapping (IM) is a systematic framework, that uses theory, empirical findings, and community input to plan evidenced-based health promotion and prevention programs. Intervention Mapping Adapt (IM Adapt) is a simplified iteration of IM that is used for adapting an established program to a new context or population. In the case of the present study, IM Adapt was used to update an established sexual health education program titled It’s Your Game…Keep It Real! (IYG), a program originally established for racial/ethnic minority middle school students. As the IYG program was established over a decade ago, IM Adapt was utilized to adapt the IYG program to the new context of the current time informed by updated empirical evidence, and to the new population of racial/ethnic minority ninth grade high school students. The updates included integrating sexual violence prevention, informed by the literature and empirical evidence. The adapted IYG program titled Your Game Your Life (YGYL) was pilot tested with ninth graders in urban areas with high teen birth rates. As this was a pilot test, there was no comparison group(s) for this study. The program was administered in fifteen 30 minute lessons, including four classroom-based lessons, four computer-based lessons, and seven blended lessons. The lessons integrated group based activities as well as skills-training activities. | Study participants (n=241) at two high schools consisted of 68% African American, and 32% Hispanic students, with 53% female and a mean age of 15.1. | Variables included: Agreement to use skills learned as measured by participants’ self-report; Having clear personal rules regarding health relationships and sex as measured by participants’ self-report; Comfortability sharing these personal rules with their partners as measured by participants’ self-report; and Use of self-regulatory decision-making paradigm as measured by self-report. | Of participants, 93% reported agreement to use the skills learned in the program. Of participants, 91% reported having clear personal rules regarding health relationships and sex. Of participants, 85% reported feeling comfortable sharing their personal rules with their partner. Of the 39 students who noted being in a situation to utilize the self-regulatory decision-making paradigm, 85% reported using this paradigm. | No follow up time was reported for this study. |

| Zinzow et al., 2018 | The intervention for this study was a peer-facilitated education program that integrated educational and interactive components regarding knowledge, attitudes, risk reduction and bystander intentions pertaining to sexual violence as well as alcohol use. The 70-minute program was facilitated by two of 24 peer facilitators per session, and was a requirement for all first-year undergraduate and transfer students at a large southeastern university in the US. Comparison was made between pre-test (baseline), posttest, and four month follow up. | The study included a total of 4911 students (n=4911) participating in the intervention, with 2767 students (56%) completing the pre-test, 2749 (56%) completing the posttest, and 995 students (20%) completing the follow up evaluation. The sample was majority white (90%) and 53% female with a mean age of 18.3 (SD = .69). | Effect Measures for the present study included: Alcohol Risk Reduction as measured by an alcohol risk reduction scale; Risky Drinking as measured by report of consumption of five or more drinks as one time over the past two weeks; Alcohol Bystander Intentions and Knowledge as measured by three items regarding information presented in the intervention program; Sexual Violence Bystander Intentions as measured by a sexual violence bystander intentions scale; Rape Myth Acceptance as measured by two items from the Rape Myth Acceptance Scale (Lonsway & Fitsgerald, 1995); and Sexual Violence Knowledge as measured by five items on the assessment. | Results indicated significant changes on all measures from the pre and posttest assessments. Results indicated significant changes were maintained at the follow up assessment on all items and scales except for two items regarding alcohol use risk, and one item regarding knowledge of alcohol-involved sexual violence. Test statistics and significance was not reported for these outcomes. | Follow-up at post intervention and four months. |

| Salazar et al., 2019 | A web-based intervention program, RealConsent, aimed at preventing sexual violence (SV) and providing bystander education was administered to 743 undergraduate college men in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) at a large university in the southeastern part of the US. Researchers used simple randomization to assign participants to the intervention group or the attention-placebo comparison group. The intervention consisted of six 30-minute online modules, which participants were encouraged to complete within three weeks. | The study included 743 male, undergraduate, hetero or bi-sexual, unmarried participants ranging in age from 18-24. | Effect measures included: Legal knowledge of assault/rape; Knowledge of effective consent for sex; Self-efficacy to intervene; Intentions to intervene; Outcome expectancies intervening; Self-comfort with men’s inappropriate behaviors (normative beliefs); Rape myth acceptance; Outcome expectancies engaging in rape; Empathy for rape victims; Hostility toward women; Date rape attitudes; and Hyper-gender ideology each measured by items on the pre-, post-, and follow-up assessments. | Participation in the intervention was significantly related to a decrease in SV perpetration as compared to control group participants (mean difference= -.28). Significant effects were shown for participants in the intervention group on all measures and on all three mediation paths tested (P<.05). | Follow up at post-intervention and six months |

The Community Guide (2018) currently recommends, with sufficient evidence, using primary prevention strategies including: teaching healthy relationship skills, the promotion of social norms including bystander intervention, and the creation of protective environments as interventions to prevent intimate partner violence (IPV) and sexual violence (SV) for youth ages 12 to 24. This recommendation is based on a systematic review inclusive of 28 studies published by June 2016. The majority of these studies found favorable outcomes in IPV or SV perpetration, victimization, or bystander action. These studies used various outcome measures, thus calculation of summary effects was not feasible for this review. However, as the included studies used a combination of so or all of the three intervention approaches as outlined above, statistically significant findings (p<.05) of favorable outcomes were present for each approach.

Following the review of three more recent studies for the current assessment, it is still recommended that the primary intervention strategies of 1) teaching healthy relationship skills 2) promoting social norms, and 3) creating protective environments be used for the prevention of IPV and SV among youth. Significant favorable results were found in each of the three recent studies, supporting the previous recommendations of The Community Guide. For example in the Zinzow et al. (2018) study, the intervention used components of all three primary interventions strategies and showed improvement in SV perpetration and bystander action measures. The Salazar et al. (2019) study similarly used intervention strategies that included primary components of teaching healthy skills and promoting social norms, and showed significant decreases in SV perpetration among college men aged 18-24 as compared to the control group (p<.05). The Markham et al., (2017) study also showed favorable improvements on outcome measures after ninth grade high school students received the Your Game your Life intervention that included primary components of healthy relationship skill building and education recommended from the previous systematic review. In sum, the outcomes of these three studies using interventions recommended previously in The Community Guide provide further evidence and support for continued use of the primary interventions (i.e. teaching healthy relationship skills, promoting social norms, creating protective environments) in the prevention of IPV and SV among youth.

Part II. Theoretical Framework/Model

Part II. Theoretical Framework/Model

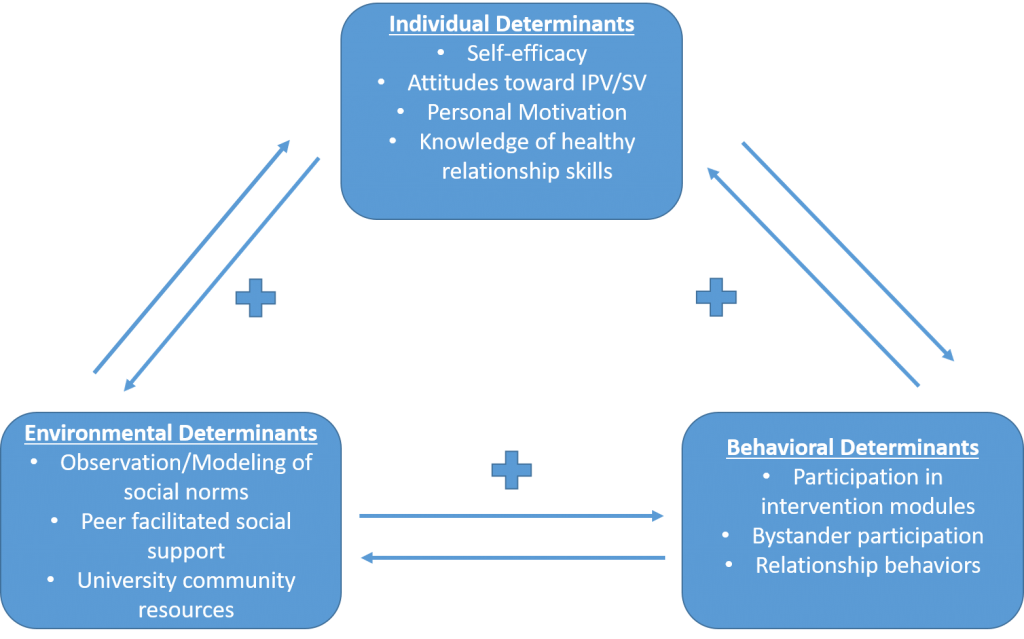

Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) is predicated on the idea that individual/personal factors, environmental factors, and behavioral factors each affect one another in an ongoing process of change (National Cancer Institute, 2005). Individual determinants include concepts such as one’s attitudes, beliefs, values, and sense of self-efficacy. Environmental determinants of change include concepts such as resources in a system or community, access, the observation of/modeling of norms or skills, and social support. Behavioral determinants include concepts such as person’s participation, actions, and behaviors regarding the concept being considered. A core tenet of SCT is reciprocal determinism, that is, each determinant in the theory affects the other determinants in a reciprocal way. The SCT was utilized as a theoretical foundation for previous studies with IPV/SV intervention programs as noted in the one of the more recent studies cited above (Salazar et al., 2019). The SCT provides an apt framework to explain how each of the factors involved in the IPV and SV prevention program will contribute to a successful intervention with the University of North Georgia Oconee campus community.

Self-efficacy: Self-efficacy is conceptualized as an individual’s confidence in their ability to perform an action or overcome obstacles to accomplishing a behavior (National Cancer Institute, 2005). The IPV/SV prevention strategies will be taught and practiced in small steps (lesson modules), a recommended change strategy to promote enhanced self-efficacy of participants (National Cancer Institute, 2005).

Knowledge of healthy relationship skills: The knowledge of healthy relationship skills applies to the concept of behavioral capability, that is, an individual possessing the know-how to and skill to perform a certain behavior (National Cancer Institute, 2005). This concept will be addressed by healthy relationship and bystander intervention skills training.

Observation/Modeling of social norms: Observational learning refers to the concept of adapting a behavior through observing a behavior and the consequences of that action being modeled by others (National Cancer Institute, 2005). In the case of this intervention, desirable healthy relationship skills and bystander action will be modeled through role plays, group activities, and vignettes addressing these skill areas to enhance prevention of IPV and SV.

Peer facilitated social support: Peer facilitated social support addresses SCT’s concept of reinforcements, defined as the consequences of one’s behavior that will enhance or diminish the probability that the behavior will be repeated. Participants’ peer will be teaching and modeling the information and skills for healthy relationships and bystander action, and supporting participants’ as they learn and practice these skills. This social support will act as a positive reinforcement for participants to persevere through the course and continue practicing these skills.

University community resources: University community resources, such as the materials, technology, space, and personnel to provide the intervention will act as a reinforcement for the strategies learned in the interventions, and contribute to the observational learning /modeling of the IPV/SV prevention strategies.

Part III. Logic Model, Causal and Intervention Hypotheses, and Intervention Strategies

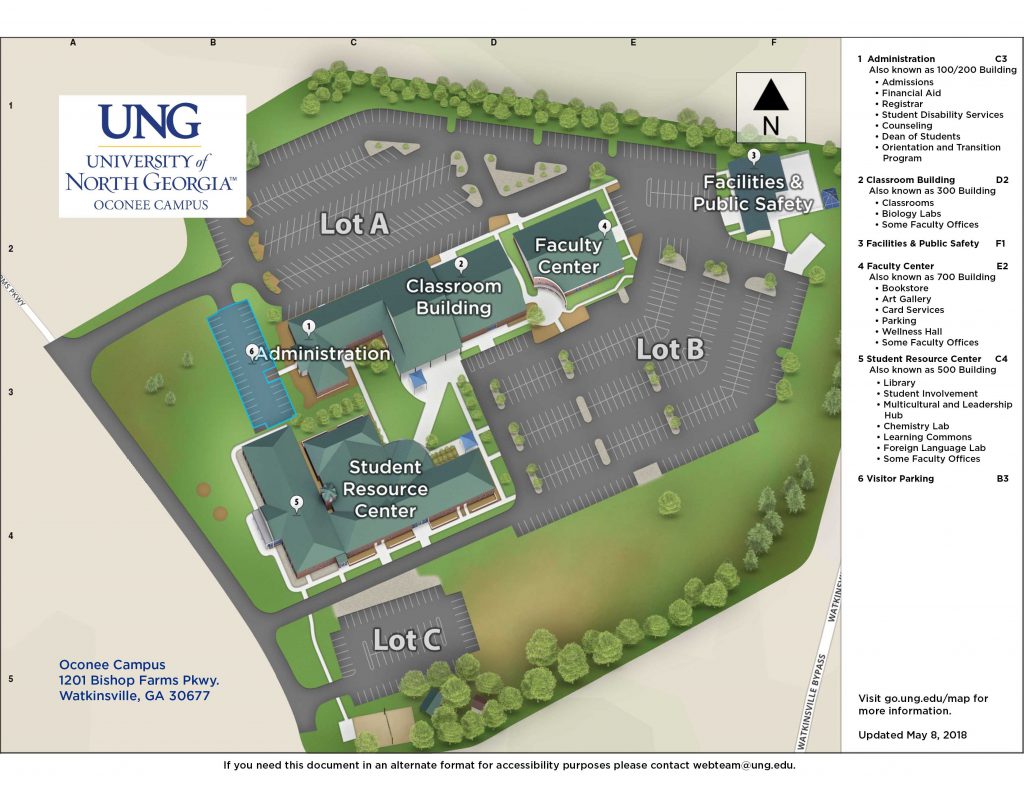

Incoming students (including new and transfer students) attending their first semester at the University of North Georgia Oconee campus (UNG-OC) in Watkinsville, GA are the target population for this intervention. College students in general, and college females specifically, are at particularly high risk for experiencing sexual violence (Salazar et al., 2014). One in five college women are victims of sexual assault during college (Carey, Norris, Durney, Shepardson, & Carey, 2018) with the majority of these assaults being perpetrated by someone the victim knows (Salazar, 2014). With college campuses being a location at higher risk of SV, and college students being a population at higher risk of experiencing some aspect of SV, it follows that targeting college students with SV prevention interventions would help address this health disparity.

UNG-OC enrolls approximately 2500 students on campus per semester, with nearly 900 of these students being new, first semester students on campus and would thus qualify for the intervention. Six intervention modules, alternating between in-person peer-facilitated groups and web-based delivery of content will be administered. With 46 peer facilitators teaching in pairs, each pair of facilitators will meet with 2 groups of 20 participants per group. The in-person modules will occur in classrooms and meeting rooms on campus.

| Intervention Method | Alignment with Theory | Intervention Strategy |

| Peer-facilitated observation/modeling of social norms | Observational learning by observing their peers model social norms, according to the SCT model, will enhance participants’ ability to reflect those social norms through their own acquisition of that behavior. Expectations, another relevant concept in SCT, are also set by peer-facilitators regarding what participants can anticipate as an outcome of their behaviors. | Each of the six intervention modules will be facilitated by college student peer-facilitators. Participants will have the opportunity to observe their peers discussing, role playing and interacting modeling the desired social norms, in regards to healthy relationships and the campus community’s norm and expectations regarding bystander action. |

| Teaching/learning healthy relationship skills, thus increasing knowledge and the skills necessary to engage in healthy relationships. | The concept of behavioral capability, per the SCT, is defined as having the knowledge and skills necessary to perform a certain action. Learning healthy relationship skills will increase the behavioral capability of participants regarding IPV/SV prevention and increase their self-efficacy. Self-efficacy, the level of confidence in one’s ability, can be enhanced through learning new skills, particularly if intervention strategies are implemented that break the learning down into small steps. | Modules will include knowledge building lessons regarding healthy relationships, communication skills, risks, social norms, and bystander intervention. Participants will be engaged in individual and group exercises to learn and practice, skills for building healthy relationships. These modules will break down the knowledge and skill building lessons into small manageable steps as a strategy to increase self-efficacy. |

| Teaching/learning prosocial bystander action, thus increasing knowledge and skills to engage in prosocial bystander action. | This intervention method aligns with the SCT via the concepts of observational learning/modeling, and behavioral capability, as participants learning about prosocial bystander action, and the related skills will contribute to both of these SCT concepts. Further, this intervention method is also grounded in the Bystander Intervention Model (BIM) for SV prevention (Baynard, Plante, & Moynihan, 2004). This intervention contributes to critical components of the BIM including: increased awareness of the problem of SV; seeing oneself as responsible for partially contributing to the solution; not viewing victims as the cause of the problems (i.e. not victim blaming); participants feeling they have the skills to intervene; and observational learning/modeling (Baynard, Plante, & Moynihan, 2004). | Intervention modules will include information about IPV/SV to increase awareness of the problem, vignettes and lessons regarding victim blaming, and knowledge building and exercises on prosocial ways participants can intervene as bystanders in IPV/SV high risk scenarios. These modules will all be taught by peer-facilitators, contributing to participants’ observational learning/modeling. |

Logic Model

| Inputs/Resources | Activities | Outputs | Short-term Outcomes | Intermediate Outcomes | Long-term Outcomes |

| The Community guide and subsequent research/literature review to guide the development of the intervention. Training week for peer-facilitators prior to the start of the fall semester. 46 student worker peer-facilitators to work in pairs. Grant to fund peer-facilitators training, development of online modules, pay for peer facilitators, the printing of workbook for participants, and printing of on-campus promotional materials. Classroom spaces reserved on campus for in-person modules. | A training week will be held in the summer prior to the start of fall semester to train the peer-facilitators on the modules. Each of the six intervention modules will be facilitated by college student peer-facilitators. Participants will have the opportunity to observe their peers discussing, role-playing and interacting modeling the desired social norms, in regards to healthy relationships and the campus community’s norm and expectations regarding bystander action. Modules will include knowledge building lessons regarding healthy relationships, communication skills, risks, social norms, and bystander intervention. Participants will be engaged in individual and group exercises to learn and practice, skills for building healthy relationships. These modules will break down the knowledge and skill building lessons into small manageable steps as a strategy to increase self-efficacy. Intervention modules will include information about IPV/SV to increase awareness of the problem, vignettes and lessons regarding victim blaming, and knowledge building and exercises on prosocial ways participants can intervene as bystanders in IPV/SV high-risk scenarios. These modules will all be taught by peer-facilitators, contributing to participants’ observational learning/modeling. | Six intervention modules, alternating between in-person peer-facilitated groups and web-based delivery of content will be administered. 46 peer facilitators teaching in pairs, 2 groups each of 20 participants. Each pair of facilitators will meet with 2 groups of 20 participants per group. The in-person modules will occur in classrooms and meeting rooms on campus. 1000 workbooks printed and given to participants (with 100 extra to replace lost books). 46 peer-facilitator workbooks. -5 large signs printed to remind students of the upcoming modules. 25 table topper flyers printed with promotional/reminder information. 138 total hours of 23 classrooms spaces reserved at bi-weekly intervals (23 hours of classroom space reserved each week). | Increase knowledge of healthy relationships, pro-social bystander action, and IPV/SV information. Develop healthy relationship skills. Develop bystander action skills. Increase self-efficacy through skill building, and observational learning/modeling. Improve behavioral capability through knowledge attainment, skills building, and observational learning/modeling. | Increase the number of students in the UNG -OC community who are aware of and knowledgeable about IPV/SV. Increase the number of students on the UNG Oconee campus who possess the skills for healthy interactions and willingness to intervene in IPV/SV situations. | Long term health outcomes for reducing/prevention of IPV/SV include: Decreasing risk for adverse mental health, bodily injury, substance abuse, and chronic physical health problems (Smith et al., 2017; Coker, et al., 2002; Campbell et al., 2002). |

Intervention Hypotheses

- Training week for peer facilitators will increase knowledge of healthy relationship skills, prosocial bystander actions and IPV/SV information.

- Intervention modules facilitated by college student peer-facilitators, will increase participants’ knowledge of IPV/SV healthy relationships, prosocial bystander action and IPV/SV information, and will increase the development of healthy relationship skills, increase relationship and bystander skills, increase self-efficacy through observational learning, and increase behavioral capability.

- Individual and group exercises will improve participants’ behavioral capability and develop healthy relationship and bystander skills.

Causal Hypotheses

- Increasing knowledge of healthy relationships, pro-social bystander action, and IPV/SV will increase the number of students in the community who are aware of and knowledgeable about IPV/SV.

- Developing healthy relationship skills will increase the self-efficacy and behavioral capability of participants regarding healthy relationships.

- Developing bystander action skills will increase the self-efficacy and behavioral capability of participants regarding bystander action.

Outcome Objectives

Goal 1: Increase knowledge of healthy relationships, pro-social bystander action, and IPV/SV information.

- Outcome Objective 1.1: 90% of participants will correctly answer 80% or more questions about healthy relationships on the posttest.

- Outcome Objective 1.2: 90% of participants will correctly answer 80% or more questions about pro-social bystander action on the posttest.

- Outcome Objective 1.3: 90% of participants will correctly answer 80% or more questions about IPV/SV on the posttest.

Goal 2: Develop healthy relationship skills.

- Outcome Objective 2.1: By the end of the sixth module, 80% or more of participants will report on the post evaluation a 30% or more increase in their self-efficacy (confidence) in their ability to practice healthy relationship skills, as compared to their pre-evaluation.

- Outcome Objective 2.2: By the fifth module, 80% or more of participants will be able to demonstrate at least three healthy relationship skills in a role-play exercise with group members, as evaluated by peer-facilitators on the healthy relationship skills checklist evaluation.

Goal 3: Develop bystander action skills.

- Outcome Objective 3.1: By the end of the sixth module, 80% or more of participants will report on the post evaluation a 30% or more increase in their self-efficacy (confidence) in their ability to practice prosocial action skills as compared to their pre-evaluation.

- Outcome Objective 3.2: By the fifth module, 80% or more of participants will be able to demonstrate at least three prosocial bystander action skills in a role-play exercise with group members, as evaluated by peer-facilitators on the prosocial bystander action skills checklist evaluation.

Goal 4: Increase self-efficacy through skill building, and observational

learning/modeling.

- Outcome Objective 4.1: 80% of Participants will report on their post evaluation a 30% or more increase in their self-efficacy in their knowledge and ability to use healthy relationship and prosocial bystander skills as compared to their pre-intervention evaluation.

- Outcome Objective 4.2: By the end of the sixth module 90% of participants will be able to list at least two skills they saw modeled by peer-facilitators during the modules on the post evaluation.

Goal 5: Improve behavioral capability through knowledge attainment, skills

building, and observational learning/modeling

- Outcome Objective 5.1: By the fifth module, 80% or more of participants will be able to demonstrate at least three prosocial bystander action skills and three healthy relationship skills in role-play exercises with group members, as evaluated by peer-facilitators on the prosocial bystander action skills checklist evaluation and healthy relationship skills checklist evaluation.

- Outcome Objective 5.2: By the end of the sixth module, 90% of participants will correctly answer 80% or more of the knowledge questions about healthy relationships, bystander action, and IPV/SV on the posttest.

- Outcome Objective 5.3: By the end of the sixth module 90% of participants will be able to list at least two skills they saw modeled by peer-facilitators during the modules on the post evaluation.

Goal 6: Increase the number of students in the UNG -OC community who are aware of and knowledgeable about IPV/SV.

- Outcome Objective 6.1: By the end of the sixth module, at least 90% of participants (810 participants) will correctly answer 80% or more of the knowledge questions about healthy relationships, bystander action, and IPV/SV on the posttest.

Part IV. Evaluation Design and Measures

| Stakeholder | Role in Intervention | Evaluation Questions from Stakeholder | Effect on Stakeholder of a Successful Program | Effect on Stakeholder of an Unsuccessful Program |

| Peer-Facilitators | Participate in the facilitator training week and facilitate the in-person modules | What components of the intervention program were most/least effective? Did my facilitation and modeling have a positive impact on participants and the university community? | Increase in knowledge about IPV/SV. Increase healthy relationship and prosocial bystander action skills. Increase confidence and competence as an effective peer-facilitator. | No increase in knowledge about IPV/SV, or healthy relationship and bystander skills. No increase and possibly a decrease in confidence as effective peer-facilitator. |

| Participants | Participate in the in-person and computer-based intervention modules. | How will my participation in the intervention modules affect my social interactions, relationships, and ability to help prevent IPV/SV? How will my participation in the intervention affect my role in the community and feelings about my community regarding safety? | Increase in knowledge about IPV/SV. Increase healthy relationship and prosocial bystander action skills. Increase confidence and competence in healthy relationship interactions and bystander interactions. Increase feelings of safety in the community. | No increase in knowledge about IPV/SV, or healthy relationship and bystander skills. No increase and possibly a decrease in confidence in healthy relationship interactions and bystander interactions. No increase and possibly a decrease in feelings of safety in the community. |

| University faculty, staff, administration | Provide a culture of support for the program and student participants and resources (e.g. classroom/campus space for modules, for flyers) for the intervention. | How will students’ participation in the program affect the campus schedule and classroom availability? How will students’ participation in the program affect the health and safety of the campus community? | Positive regard for the program and interest in continuing support of the intervention. Increased feelings of safety in the community. | Negative thoughts and feelings about the program. Reluctance to continue providing support for the program in the future. Decreased feelings of safety in the community. |

| Grant funders | Provide funding for the peer-facilitator training week, the development of the online modules, pay for facilitators, printing of the workbooks, and printing of on-campus promotional materials. | Is the program reaching the goals it stated in the grant proposal? Is the program worth effective in preventing IPV/SV? Is the funding being used for the purposes for which it was allocated? | The peer-facilitator training, computer modules, workbooks, and promotional materials will contribute to the program accomplishing its stated goals. Grant funders will be motivated to continue support of the program. | Funders will feel that their resources were not well allocated (i.e. used on an ineffective program) and be reluctant to offer support in the future. |

| University System of Georgia (USG) Board of Regents (BOR) | Develop policies regarding IPV/SV prevention on University System of Georgia campuses. Provided a culture of support for the intervention program. | Does the program enhance students’ knowledge and skills regarding IPV/SV prevention? Does the program help to prevent or reduce IPV/SV in university communities? Does the program enhance university community members’ sense of safety in the community? | Encourage further support for the intervention program being used. Possibly encourage expansion of the program to other USG campuses. | Negative thoughts and feelings about the program. Reluctance to continue providing support for the program in the future. |

| Community sexual assault centers, IPV support center, police, medical workers, other students and members of the community | As organizations who work with and are affected by IPV/SV in the wider community (Oconee County, Athens-Clarke County), and work with UNG-Oconee students, they will provide a culture of support for the intervention program. | Is this program effective at enhancing preventative factors that contribute to prevention of IPV/SV in the community? Is the program providing accurate information and is it an evidenced-informed intervention? | Increased confidence in and cultural support of the program. | Negative regard for the program and decreased support of the program in the future. |

Outcome Evaluation Design: Quasi-experimental one-group pre- and post-test design

The outcome evaluation study design will be a quasi-experimental one-group pre- and post-test study, with a follow up post-test six months later. The group will be approximately 900 new, first semester students (including transfer students) on UNG’s Oconee campus. The group will be given a pre-test prior to the start of the first intervention module, and a post-test after the conclusion of the intervention.

O1 TX O2 O3

[O1 = pre-test prior to beginning first intervention module O2 = post-test at the conclusion of the final intervention module O3 = Follow up post-test six months after conclusion of intervention.]

The test will assess: participants’ knowledge of healthy relationships, pro-social bystander action, and IPV/SV information (Goal 1 & 6), healthy relationship skills (Goal 2 & 5), bystander action skills (Goal 3 & 5), participants’ self-reported self-efficacy (Goal 4).

Threats to internal validity

As with any study design, threats to internal validity exist. However, upon consideration, due to the risks associated with IPV/SV, and the importance of implementing prevention programming for college students, the benefits of single group design outweighed the threats to internal validity. Nonetheless, efforts have been made to limit these threats to the extent possible. The main threats to internal validity for this quasi-experimental pre- and post-test single group design include maturation, history, attrition, and testing. The threat of maturation exists, as participants may naturally increase their knowledge of the subject matter over the course of their first year at college. History is also a threat to internal validity in this case, as other experiences or phenomena that participants’ may encounter over the course of the study, as opposed to the intervention, may account for changes in test scores. The amount of time between pre- and post-test being a short six week will help to mitigate these two threats (maturation and history). Attrition, or participants not remaining in the study, is also a threat to internal validity as participants who remain in the study may be more motivated regarding this topic. However this threat will be somewhat mitigated by the use of pre- test, as researchers can evaluate differences between those participants who did and did not complete the program. Finally, testing is a threat to internal validity, as just the act of taking the first test, may affect the results of the second test. In an effort to limit this threat, researchers will remain aware of the natural learning curve associated with taking a pre-test, particularly during data analysis.

| Short-term or Intermediate Outcome Variable | Scale, Questionnaire, Assessment Method | Brief Description of Instrument | Example item (for surveys, scales, or questionnaires) | Reliability and/or Validity Description |

| Increase knowledge of IPV/SV information, healthy relationships, and pro-social bystander action. | This questionnaire measures participants’ legal knowledge of IPV/SV, consent, and rape myth acceptance (Salazar et al., 2017). | This questionnaire includes three scales including: (1) Legal knowledge of assault/rape, with 9 true/false questions, (2) Knowledge of effective consent for sex, with 14 true/false questions, and (3) Rape myth acceptance, with 17 Likert style items from 1(not at all comfortable) to 7 (extremely comfortable). Regarding bystander action a fourth scale assesses for (4) Outcome expectancies when intervening, with 8 items in Likert style from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). | Examples of items from each of the scales include: (1) “In the state of Georgia, it is always legal to engage in sexual intercourse with a person under the age of 16 so long as he or she gives consent?” (2) “If a woman doesn’t physically resist sex, she has given consent.” (3) “Rape happens when a man’s sex drive gets out of control.” And, (4) “If I intervene, I can prevent someone from being hurt.” | The first two scales according to Salazar et al. are “considered indexes and comprise items deemed “causal indicators,” which indicates items are not necessarily correlated; thus, internal reliability was not calculated for these indexes because it is not an appropriate method to assess reliability. (2017). The third scale regarding rape myth acceptance notes a Cronbach’s alpha of .86 for internal consistency. The fourth scale regarding bystander intervention has a Cronbach’s alpha of .80. |

| Develop/increase healthy relationship skills | This measure assessed respondents knowledge and use of dating relationship maintenence skills (Rice, McGill, & Adler-Baeder, 2017). | This measure includes a total of 8 items. Four items assess for respondents’ knowledge of healthy relationship skills using a Likert scale from 1 (poor) to 4 (excellent). Four additional items assess for respondents’ use of relationship maintenance skills using a Likert scale from 1 (never) to 4 (regularly). Composite scores are then created by averaging the items in each sub-scale. | The first sub-scale used items such as ‘‘My knowledge of ways to demonstrate kindness, affection, and respect for my dating partner was/is___.” An example of items used in the second sub-scale is ‘‘I ____ made/make efforts to develop and maintain a healthy dating relationship.” | Internal consistency for the first sub-scale at post-test as measured by Cronbach’s alpha is .81 and for the second sub-scale at post-test is .87. |

| Develop/Increase prosocial bystander action knowledge and skills | This survey (The BIH) measures participants’ willingness or probability to engage in pro-social bystander action (Baynard, 2008; Baynard, Moynihan, Cares, & Warner, 2014). | This questionnaire is has 32 items, all Likert-scale, with 16 items inquiring about helping friends, and 16 item asking about helping strangers. Scores on each subscale range from 16 to 80, with higher scores indicating an increased likelihood of bystander action. | No verbatim example items were given (due to copyright access), but items were noted to ask a series of questions about how likely a respondent would be to respond to witnessing friends or strangers in hypothetical scenarios regarding witnessing IPV/SV risk situations. | The overall internal consistency for this scale measured by Cronbach’s alpha is .94. |

| Increase self-efficacy through skill-building and observational learning/modeling | This scale measures participants’ self-efficacy to intervene in situations at risk for SV (Salazar et al., 2017). | This 18 item questionnaire asks respondents to indicate their confidence level to intervene in situations of potential IPV/SV on a seven point Likert scale from 1 (not at all confident) to 7 (extremely confident). | An example of items on this scale is “Indicate my displeasure when I hear a sexist comment.” | The internal consistency of this scale is .95 (Cronbach’s alpha). |

Part V. Process Evaluation and Data Collection Forms

Recruitment and Enrollment: An email will be sent to each incoming student (the list will be gleaned from the UNG Banner Web system that the university uses for enrollment, grades, etc.) prior to their New Student Orientation (NSO) date, informing students of the requirement for all incoming students to participate in IPV/SV prevention program. This email will provide information about the program, and contact information for any questions they may have about the program. Students will be registered for their intervention groups (including dates/times/locations) when they register for their classes during their NSO. Students who miss this main registration opportunity can register when they meet with their adviser to register for classes.

Tabletop flyers and posters (like the one below) will be placed on tables around campus the week prior to in-person modules to remind participants of the upcoming meetings.

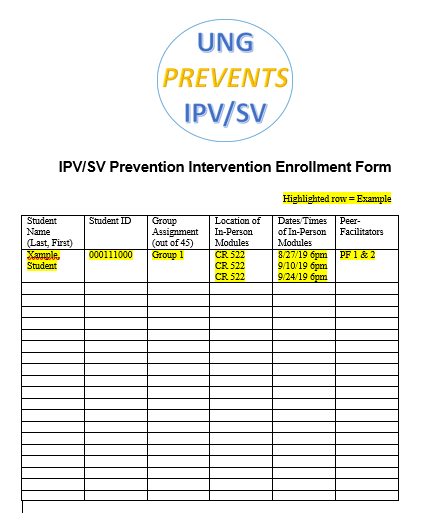

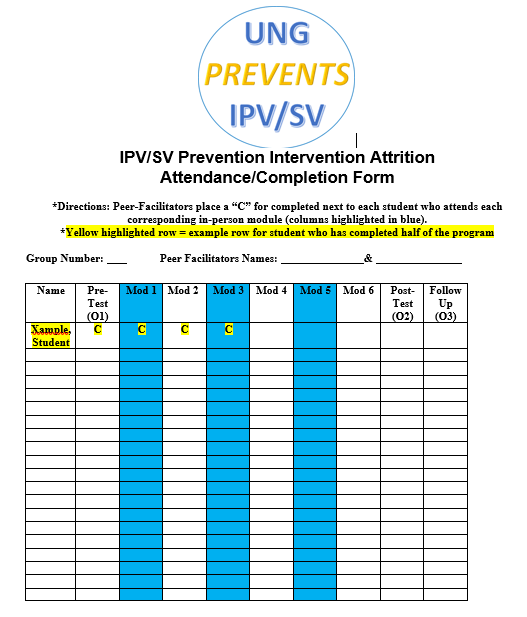

Enrollment will be tracked using the form below and cross-referenced with the complete list of new students to assess which students did and did not enroll. Students who do not complete all six modules will receive a hold on their registration for the following semester, to meet with advisers and set up a program completion plan.

Attrition: Upon registration, students will receive an email with a link to the first evaluation (O1). Completion of this evaluation will be required to attend the initial intervention module (in-person). Computer labs will be available for students to complete the evaluation prior to the first module if needed. Peer-facilitators will be able to see and check the attendance/attrition form (below) to ensure each step is completed prior to the next one beginning (i.e. completion of the first evaluation, will electronically open up the ability to mark attendance at the first module. In turn attendance at the first module will open up the link for student to do the second, computer module, and so on). The follow-up evaluation (O3) six months later will be sent to students via email with a link to the evaluation and to the incentive drawing for completing the follow-up evaluation.

Fidelity of the Program: The following surveys (see below) will be given to students at the end of the sixth intervention module to assess for fidelity of the program.

1. I was provided with an opportunity to attend 3 in-person modules on IPV/SV prevention

—– Yes —– No

2. I was provided with an opportunity to complete 3 computer modules on IPV/SV prevention

—– Yes —– No

3. Two peer-facilitators conducted each of the in-person modules

—– Yes —– No

4. An on-campus space (e.g. Classroom, workroom, etc.) was provided for our group each time we met for an in-person module

—– Yes —– No

5. I received an IPV/SV prevention workbook to use for the program

—– Yes —– No

6. If applicable, I received a workbook to replace a lost or misplaced workbook

—– Yes —– No —– N/A

7. There were signs around campus (e.g. on tabletops, on display boards) that reminded students about the program

—– Yes —– No —– Don’t Know

8. I received helpful information about healthy relationships in this program

Strongly Agree Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly Disagree

9. I received helpful information about how to intervene as a bystander in situations where sexual violence may potentially occur

Strongly Agree Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly Disagree

10. I received information that helped me understand the facts about interpersonal violence (IPV) and sexual violence (SV)

Strongly Agree Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly Disagree

11. I received skills training on how to engage in healthy relationships (e.g. how to ask for consent

Strongly Agree Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly Disagree

12. I received skills training on how to intervene as a bystander in situations where sexual violence may potentially occur

Strongly Agree Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly Disagree

13. As a result of participating in this program, I feel more confident in my ability to engage in healthy relationships

Strongly Agree Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly Disagree

14. As a result of participating in this program, I feel more confident in my ability to intervene as a bystander in situations where sexual violence may potentially occur

Strongly Agree Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly Disagree

15. As a result of participating in this program, I feel more capable to engage in healthy relationships

Strongly Agree Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly Disagree

16. As a result of participating in this program, I feel more confident in my ability to intervene as a bystander in situations where sexual violence may potentially occur

Strongly Agree Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly Disagree

17. Please note any additional comments or feedback you would like to share about your experience in this program below:

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

References

Banyard, V. L., Plante, E. G., & Moynihan, M. M. (2004). Bystander education: Bringing a broader community perspective to sexual violence prevention. United States: Clinical Psychology Publishing Co Inc. Retrieved from http://proxy-remote.galib.uga.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsbl&AN=RN143173665&site=eds-live

Banyard, V. L. (2008). Measurement and correlates of prosocial bystander behavior: The case of interpersonal violence. United States: Springer Publishing Co. Retrieved from http://proxy-remote.galib.uga.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsbl&AN=RN225139244&site=eds-live

Banyard, V. L., Moynihan, M. M., Cares, A. C., & Warner, R. (2014). How do we know if it works? Measuring outcomes in bystander-focused abuse prevention on campuses. Psychology of Violence, 4(1), 101-115. doi:10.1037/a0033470

Campbell, J. C. (2002). Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet, 359(9314), 1331. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8

Carey, K. B., Norris, A. L., Durney, S. E., Shepardson, R. L., & Carey, M. P. (2018). Mental health consequences of sexual assault among first-year college women. Journal of American College Health, 66(6), 480-486. Retrieved from http://proxy-remote.galib.uga.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eric&AN=EJ1190711&site=eds-live http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2018.1431915

Coker, A. L., Davis, K. E., Arias, I., Desai, S., Sanderson, M., Brandt, H. M., & Smith, P. H. (2002). Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. United States: Elsevier Science B.V., Amsterdam. Retrieved from http://proxy-remote.galib.uga.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsbl&AN=RN121429809&site=eds-live

Lonsway, K., & Fitzgerald, L. F. (1995). Attitudinal antecedents of rape myth acceptance: A theoretical and empirical reexamination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(4), 704-711. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.68.4.704

Markham, C. M., Peskin, M., Shegog, R., Cuccaro, P., Gabay, E. K., Johnson-Baker, K., Swain-Ogbonna, H.L., Edwards, S., & Tortolero, S. R. (2017). Reducing sexual risk among racial/ethnic-minority ninth grade students: Using intervention mapping to modify an evidenced-based curriculum. Journal of Applied Research on Children, 8(1) Retrieved from http://proxy-remote.galib.uga.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eric&AN=EJ1188321&site=eds-live

National Cancer Institute (U.S.). (2005). Theory at a glance: A guide for health promotion practice (2nd ed.). Bethesda, MD: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute.

Rice, T., McGill, J., & Adler-Baeder, F. (2017). Relationship education for youth in high school: Preliminary evidence from a non-controlled study on dating behavior and parent-adolescent relationships. Child & Youth Care Forum, 46(1), 51-68. doi:10.1007/s10566-016-9368-8

Salazar, L. F., Vivolo-Kantor, A., Hardin, J., & Berkowitz, A. (2014). A web-based sexual violence bystander intervention for male college students: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(9), e203. doi:10.2196/jmir.3426

Salazar, L. F., Vivolo-Kantor, A., & McGroarty-Koon, K. (2017). Formative research with college men to inform content and messages for a web-based sexual violence prevention program. Health Communication, 32(9), 1133-1141. doi:10.1080/10410236.2016.1214219

Salazar, L. F., Vivolo-Kantor, A., & Schipani-McLaughlin, A. (2019). Theoretical mediators of “RealConsent”: A web-based sexual violence prevention and bystander education program. Health Education & Behavior, 46(1), 79-88. Retrieved from http://proxy-remote.galib.uga.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eric&AN=EJ1202758&site=eds-live http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1090198118779126

Smith S, Chen J, Basile K, et al. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010-2012 State Report. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017.

Zinzow, H. M., Thompson, M. P., Goree, J., Fulmer, C. B., Greene, C., & Watts, H. A. (2018). Evaluation of a college sexual violence prevention program focused on education, bystander intervention, and alcohol risk reduction. College Student Affairs Journal, 36(2), 110-125. doi:10.1353/csj.2018.0019