| Author & Year | Intervention Setting, Description, and Comparison Group | Study Population Description and Sample Size | Effect Measure (Variables) | Results, Including Test Statistics and Significance | Follow-Up Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rilie, Margaret, Laurie, Anna, Plegue, Melissa, & Richardson, Carlene; 2016 | The setting is the University of Michigan Hospital Health Systems Regional Alliance for Healthy Schools, which runs six school-based health centers in low income neighborhoods | The study population consists of adolescent patients from the Ypsilanti Health Center; participants were chosen because they were patients at the health center and a medical records check showed that they were missing some kind of recommended medical service; for each service, the controls did not attend a school with a school-based health center *Numbers in the control and case groups varied depending upon the variable: Asthma study: 20 in the study group, 100 in the control group *nutrition counseling: 103 in the study group, 508 in the control group *Well-child visit group: 192 in the study group; 1279 in the control group | *Following a recommended asthma plan *Receiving needed nutritional counseling *Attending a missed well-visit | *19% increase in the percentage of teens with asthma following an asthma plan (13/20 in the study group….65%....vs. 46/100 in the control group….46%....p-value .19. *33.7% increase in the number of teens in need of nutrition counseling receiving it (50/103….48.5%...in the study group vs. 75/508….14.8% in the control group) *Well-child visit 5.8% increase (137/192….71.4% in the study group vs. 839/1279…65.6% in the control group) | Baseline 12 months and intervention period 10 months |

| Cornwell, Macey; 2018 | The intervention setting is a rural community in Kentucky; the participants served as their own controls | *450 clinic patients invited; 129 accepted the invitation to participate *62% (n=80) were female *27% (n-34) were 9th-12th graders *36% (n=45) were full-time school employees | *Number of emergency room visits for non-emergency situations *Patients’ perceived access to healthcare *patient satisfaction | 1) Patients experienced statistically significant reductions in needing to go to the emergency room for non-emergency care (Based on the Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test (t=4.2; p=<0.0001 2) * 60% of participants strongly agree that the clinic has increased their access to healthcare; 37% agree; 3% were neutral (p=<0.001) | January 1st, 2018-September 31, 2018 |

| Paschall, Mallie & Bersamin, Melina, 2018 | The authors studied the large dataset cross-sectional survey of the Oregon Healthy Teens data, which is part of the Youth Risk Behavior Survey administered once per year in all public schools willing to participate | *168 public schools in Oregon participated, 25 had SBHCs, 14 of these drastically increased their availability of mental health services (both acute care and long-term care) | *School-wide prevalence of student-reported depressive episodes, suicide ideation, and suicidal attempts | *Multilevel regression was completed, controlling for age, race, gender, ethnicity, and SES (as measured by school free and reduced lunch) *Schools whose health centers increased their mental health services saw a statistically significant decline in self-reported depressive episodes among students than those which did not add mental health access (OR=0.82, 95% CI .72, .93); Schools with increased access to mental health services saw statistically significant reductions in suicide ideation (OR =.81, 95% CI: .69, 0.94, p <0.01 *Reduced suicide attempts (OR=0.92, 95% CI=0.73, 1.17) | 3 years |

| Bersamin, Melina; Coulter, Robert; Gaarde, Jenna; Garbers, Samantha; Mair, Christina & Santelli, John, 2018 | The study examined the relationship between SBHCs and school connectedness. Cross-sectional data from 503 California public high schools in were examined using multiple regression analysis. | *The study group (students in schools with a SBHC ) was 36, 892 students. The control group (students without a SBHC in their school) was 263, 108 students. Study Group: Black: 2,632 White: 3,369 Hispanic: 17,103 Asian: 10, 610 Control Group: Black: 8,927 White: 63,431 Hispanic: 131, 706 Asian: 32, 721 | The researchers examined the interaction between availability of health centers, students’ SES and parents’ level of education and their perceptions concerning adult caring, adult expectations that they did their best everyday, and meaningful participation in school activities | Among students whose parents had an education equal to or less than a high school diploma scores for perceptions of adult caring were up 0.06 points (p=0.01), scores for adult expectations increased 0.04 (p=0.01) , and scores for meaningful participation in school activities increased 0.03 (p=0.01). | 1 year |

Part 1: Community Guide Update and Rationale for Intervention

The Community Preventive Services Task Force (CPSTF) currently recommends the implementation and maintenance of school-based health centers for the purpose of improving educational and health outcomes. This recommendation is based upon a systematic literature review of 46 studies completed before 2014. We reviewed four studies since the Task Force’s recommendations and found that the more recent studies have found similar results to previous studies, and so there is sufficient evidence to continue with the task force’s evaluation of, “Recommended,” for school-based health centers.

Impact on Adolescents’ Mental Health

One of the areas the Task Force considered in its systematic Review was the effect of school-based health centers on adolescents’ mental health. Paschall, M. & Bersamin, M. (2018) used the Oregon Healthy Teens Survey, part of the national Youth Risk Behavior Study, to compare self-reported reductions in depressive episodes, suicide ideation, and suicide attempts. The results showed that school-based health centers which provide a range of both acute and long-term mental health care can be very effective in improving students’ mental health. Specifically, students attending the schools in the study population had a protective OR of 0.82 (95% Confidence Interval .72, .93), a protective OR of .81 for suicidal ideation (95% Confidence Interval .69, 0.94) and a reduction in suicide attempts that was not statistically significant (protective OR of 0.92, Confidence Interval 0.73, 1.17). Though the measures are a little different than in the previous studies, it appears these results are at least as favorable as those the Task Force used.

Impact on Preventive Healthcare Access

Additionally, the original Task Force evaluated six studies regarding the access to preventive healthcare. We considered two relevant new studies in this area: Cornwell, M. (2018) and Rilie, M., Laurie, A., Plegue, M. & Richardson, C. (2016). The former evaluated the variable of access to care at a rural clinic in Kentucky. All 450 staff and student patients received invitations, and 129 participated. The study didn’t provide percentages, but reduction in patients needing to visit the emergency room for non-emergency care was significant based on a t-value of 4.2 on the Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test with a very persuasive p-value of < 0.0001. Similarly, 97% of clinic users reported statistically significant increased access to healthcare (60% strongly agreed, nobody disagreed, and just 3% of patients were neutral (Cornwell, M., 2018). The latter study examined six school-based clinics in rural Michigan. The researchers saw a 19% increase in the percentage of teens with asthma following an asthma plan (which matched the median decrease of asthma morbidity of 19.3% across two studies evaluated by the Task Force precisely). Previous studies showed an average increase of 12% in use of preventive services, but this study demonstrated a 33.7% rise in students receiving nutrition counseling, which is significantly higher. Similarly, attendance at well-child visits in this study increased by 5.8%, over twice the 2.2% found by the Task Force.

New Consideration: Impact on School Connectedness

Finally, over the past few years, a new focus area in school-based health center research has emerged: school connectedness evaluation. Bersamin, M., Coulter, R., Gaarde, J., Garbers, S., Mair, C. & Santelli, J. (2018). The researchers examined cross-sectional health survey data from 36,892 study group participants and 263, 108 control group students. Students were asked to rate from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much so) questions about their school connectedness. The variable of caring relationships was measured by the survey item, “At my school there is a teacher or other adult who really cares about me.” The variable of teacher expectations was measured by the item, “At my school there’s a teacher or some other adult who always wants me to do my best.” Finally, meaningful involvement was measured with the item, “At my school I do things that make a difference.” To make policy recommendations about areas where school-based health centers would be most effective, the authors used multiple logistic regression to examine the possible interaction between students’ access to health centers, their parents’ level of education, and their feeling of connectedness to the school. A relevant finding is that for the overall student population as a whole, no statistically significant relationship was found between the presence of a school-based health center and students’ feelings of connectedness to school. However, by examining students by groups, the researchers found that among students whose parents had less than or equal to a high school diploma, the outcomes changed. These students reported an increase in 0.06 points on feelings adults cared about them, a rise of 0.04 for the question about adult expectations, and 0.03 rise on the question about meaningful participation (Bersamin, Coulter, Gaarde, Garbers, Mair & Santelli, 2018). In conclusion, the new studies show results that demonstrate similarly positive (and sometimes higher) positive effects than the previous studies examined by the Task Force. Improvement in the additional variable of school connectedness has also been proposed in recent research. That’s why we elect to keep the evaluation at, “Recommended.”

Part 2: Theoretical Framework and Model:

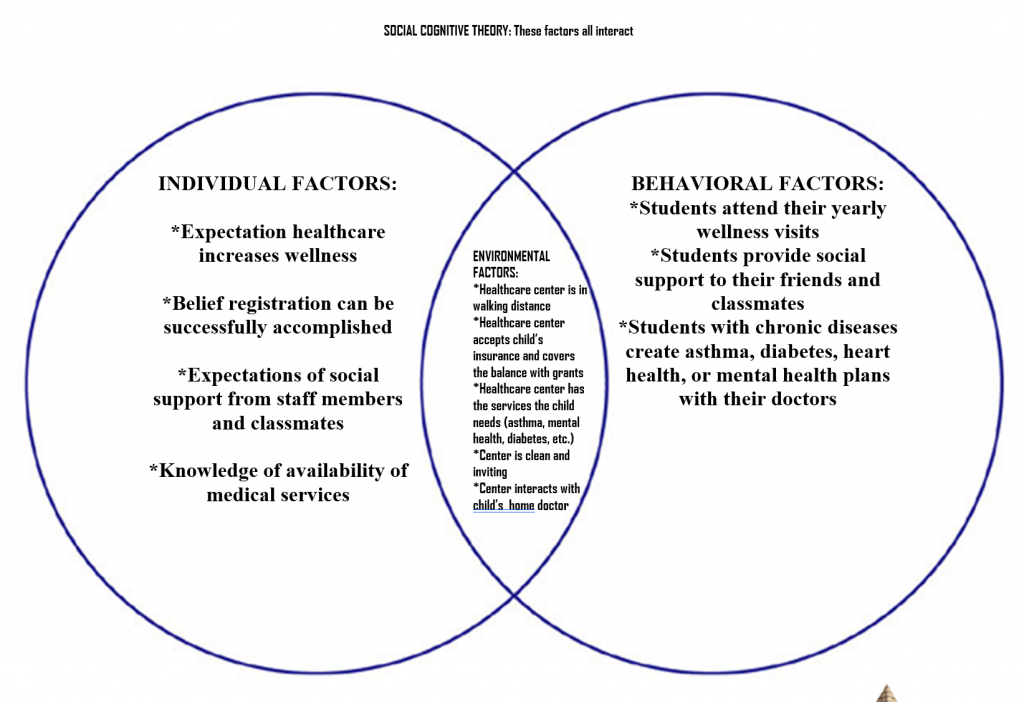

Social Cognitive Theory is a conceptual model concerning how individuals learn. It was created by Albert Bandura, who taught psychology at Stanford University (Vinney, 2019). It addresses how individuals affect and in turn get formed by their interactions with their environment. In 1977, Bandura conceived Social Learning Theory, in which he posited that learning is an interactive process, whereby people learn positive and negative behaviors through watching others and imitating their actions. He later revised the model into Social Cognitive Theory to stress the importance of the thought processes that exist during the process (Vinney, 2019). Many theories address only an initial behavioral change; however, SCT is unique in its consideration of how individuals self-monitor continual actions in order to maintain goal-setting behaviors (Lamorte, 2018). Self-efficacy is the newest component of the concept, built on when the Social Learning Theory was revised into Social Cognitive Theory (Lamorte, 2018). This theory will explain how children who may have had limited encounters with medical services learn to use School-Based Health Centers to improve their health and well-being.

- Reciprocal Determinism: this is the background of the model. It is the three-way interaction between an individual and his or her personal history, the environment, and emerging behaviors (defined as when an individual engages in actions that achieve some kind of desired goal) (Lamorte, 2018). The implementation of a school-based health center provides a change of environment for the children of Decatur, GA. The goal is that they themselves will impact the environment through having the chance to share their wishes for a health center. (For example, they may perceive their most essential health need as acute care: a doctor’s visit or medications when they are sick or they may realize that they have untreated asthma and desire services.) In turn, the goal is that the students will be impacted by the change of environment of the health center and will learn to attend the health center for acute as well as long-term health needs, such as treatment for depression or vaccinations.

- Behavioral Capability: This part of the model posits that an individual can perform a desired behavior because he or she has the needed information and skills (Lamorte, 2018). Students will work in their homerooms during advisement and during their Health and Physical Fitness classes to monitor their own vaccine history, medical records, and mental health (through self-administered mental health assessments). They will receive information through videos and presentations from local nurses and health professionals regarding how to use the services of a health center to manage and prevent chronic diseases. They will practice role-playing asking their parents if it’s okay if they can use the health center and practice asking their teachers when would be an appropriate time to visit. They will complete practice appointment request cards to ensure they have the skills to seek care.

- Observational Learning: This part of the theory explains that learning is a social process. People watch others perform actions and then repeat what they see (Lamorte, 2018). Student leaders, such as cheerleaders, football players, members of the dance team, student council, and homecoming court, will be selected to be some of the first students to visit the new school health center. They will then visit homerooms and health classes as well as create posters and maybe short videos for morning announcements explaining how the school health center helped them and encouraging other students to attend. (Students’ privacy will of course be honored; no student will be encouraged to share personal health information if he/she is reluctant or if it is confidential.)

- Reinforcements: The individual will change internally as a response to the environment and the environment will give feedback regarding the changes an individual makes (Lamorte, 2018). Children who received their recommended vaccines will feel proud they are taking care of themselves. Children who develop an asthma action plan will breathe more easily. Children who receive nutritional counseling as needed will have the knowledge to lose weight and will gain confidence about their appearance.

- Expectations: This section of the theory explains that an individual expects some kind of outcome to occur in response to his or her behaviors. Individuals who place value on said effect are more likely to exert effort to achieve it (Lamorte, 2018). In health class children will watch videos showing the difference in quality of life between individuals who manage their asthma as compared to those who do not. Children will research the Measles vaccination crisis occurring around the world to learn the importance of staying up-to-date with all recommended vaccines.

- Self-Efficacy: This describes an individual’s confidence that he or she is capable of performing a behavior due to one’s own skills or knowledge. It also can be based upon one’s knowledge of related barriers and supports (Lamorte, 2018). Children have little say over their own access to healthcare. They are not the purchasers or holders of health insurance, and they lack transportation to visit a doctor and are unlikely to have their own money to pay for services. Further, most of the time they cannot consent to their own treatment without their parents’ or guardians’ permission. Historically, these factors all cause significant hurdles to children seeking and receiving healthcare. School-based health centers have the potential to significantly increase children’s feelings of self-confidence. If their parents sign permission at the beginning of each school year, they can independently walk to treatment any time they choose. If children without health insurance receive grant funding to receive care any fears that their health needs will cause hardship to their families will be eased. These factors will increase competency in seeking care.

Part 3: Logic Model, Causal and Intervention Hypothesis, and Intervention Strategies

Target Population:

The intervention will be targeted for adolescents from low income households, in between the ages of 11 to 14 years (middle school) in the Decatur, Georgia area. Decatur is located five miles northeast of downtown Atlanta. During the 1960s and 1970s property values fell dramatically, causing economic distress in the area. Though the city of an estimated population of 20, 000 has seen some progress, huge racial discrepancies now remain (http://www.city-data.com/city/Decatur-Georgia.html). Specifically, it is one of the cities in Georgia that received a grade of F for Minority Social and Economic Indicators from the Georgia Health Equity Initiative (Georgia Health Equity Initiative, 2008). A grade of F means that racial minorities in a given county have disturbingly poor wellness and that racial inequity is severe (Georgia Health Equity Initiative, 2008). Another indicator that received failing marks was in Primary Care Access. This means that the location would be a perfect location for a school-based health center because it could reduce disparity by serving as the Primary Care facility for children who lacked healthcare. Reproductive Health Outcomes were rated at B-, meaning that moderately high racial differences in access exist (Georgia Health Equity Initiative, 2008). Therefore, adding reproductive health services to the school-based health center would provide access to young females in need. Further, mental health indicators received a grade of C-, which shows that a combination of below expected outcomes are worsened by severe racial inequality, so the plan to add mental health services to the school would be justified (Georgia Health Equity Initiative, 2008). Finally, 21.3% of individuals have no insurance, and 4.7% speak no English at home (Georgia Health Equity Initiative, 2008).

Intervention Mapping

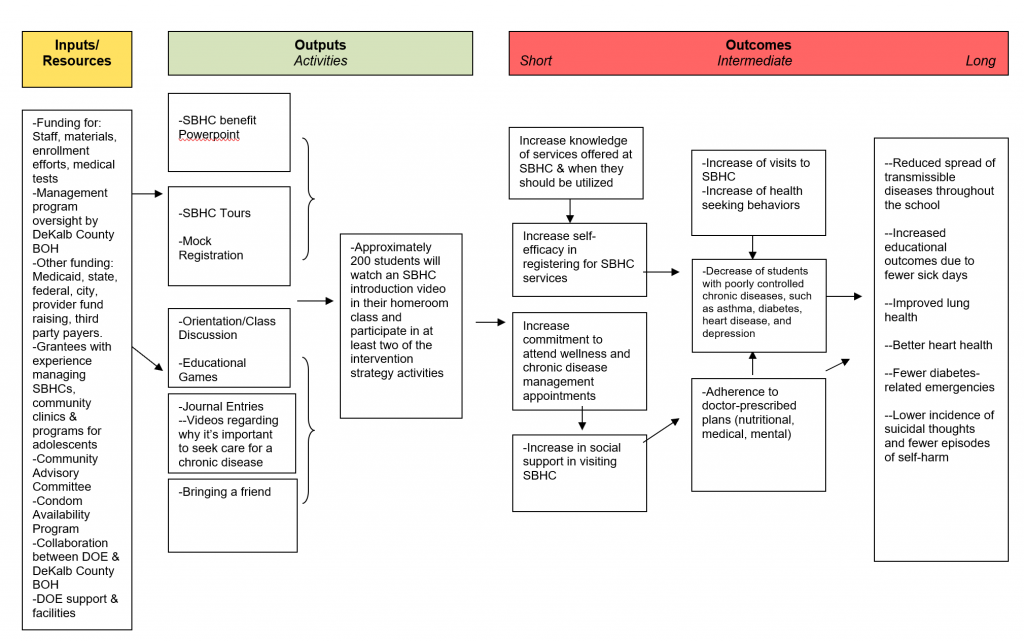

| Intervention Method | Alignment with Theory | Intervention Strategy |

| Build self-efficacy | Social Cognitive Theory explains that individuals will be more likely to perform an activity that they feel they can perform successfully. Based on this theory, if students know they can successfully go through the steps required to gain treatment at the health center, they will be more likely to take control of their health needs by utilizingk the services of the health center. | During advisement time groups of students will take a tour of the health center. They will meet the employees and have a chance to see all the rooms and equipment available. They will participate in a mock registration activity by completing practice paperwork. |

| Increase knowledge of the services available at the school-based health center. | Social Cognitive Theory explains that when children have knowledge, they build behavioral capacity. By understanding the services that are available at the school-based health center, such as acute medical assistance, long-term disease management, and reproductive health services, children gain the capacity to seek treatment. | Staff from the school-based health center will visit to teach students which services are available at the health center and how and when to get treatment. They will run through a Powerpoint, hold a class discussion, and then play an educational game using the classroom Smartboard. |

| Build Social Support | Social Cognitive Theory says that individuals practice new behaviors when they have Social Support. Visiting the health center to create an action plan for chronic disease control, possible vaccinations (if afraid of needles or side effects) or especially to seek reproductive services could be intimidating the first time. Students are encouraged to bring a friend with them for social support when they attend their visits. | Students will write a short journal paragraph in their health class as a class opener regarding who they would bring with them to a doctor’s visit and why and then be encouraged to share their responses with a classmate or the whole group. For closure, the teacher will encourage students to follow up on their plan by bringing a friend to their appointment for social support. |

| Increase Commitment to follow any wellness plans that were created at wellness visits. | Based on Social Cognitive Theory, Outcome Expectations demonstrate that when students value the outcome of a behavior, they are more likely to exert effort to achieve it. | Students will watch videos about chronic disease management. The main characters in the videos will be other teenagers or young adults who have successfully controlled their chronic diseases such as asthma and how collaborating with a health professional made it possible. The videos will also feature health professionals explaining the improvement in overall quality in life that is a result of managing one’s health conditions effectively. Students will be given write about a chronic health condition they have and to create a commitment to seek medical treatment for it. If they do not have a chronic disease themselves, they can journal about a loved one with a chronic condition and some steps he or she could take to stay healthy. |

School Based Health Center Logic Model

Intervention Hypothesis

1.The tour will build self-efficacy because the children will practice completing needed paperwork and scheduling an appointment.

2. The Powerpoint, class discussion, and game will build behavioral capacity by giving students the knowledge of services available in the school-based health center.

3. Bringing a friend to wait in the waiting room of the health center will build social support.

4. The journal entries will increase participants’ commitment to follow a wellness plan if prescribed by their doctor.

Causal Hypothesis

- Building social support will decrease spread of transmissible diseases because students will encourage their friends to attend the health center for acute care visits.

- Increasing self-efficacy will increase the percentage of students attending annual wellness visits and following up with recommended care.

- Building knowledge of the services available will result in improved lung and heart health, fewer diabetes-related emergencies, and reduced incidence of suicidal thoughts and self-harm episodes.

- Commitment to follow a wellness plan recommended by a physician will result in improved lung and heart health, fewer diabetes-related emergencies, and reduced incidence of suicidal thoughts and self-harm episodes.

SMART OUTCOME OBJECTIVES

Goal 1: Increase knowledge of services available at the school-based health center and when they are needed.

- Outcome 1: At the end of week 16, participants will be able to pass a knowledge test regarding services offered by the school-based health center and when they should be utilized with a 70% or higher.

- Outcome 1: At the Week 16, participants will be able to demonstrate to a new classmate how to complete the registration paperwork and make an appointment.

Goal 2: Increase feelings of self-efficacy in the area of self-care.

- Outcome 2.1: By week 8, the number of participants who report low feelings of self-efficacy in finding and accessing health treatment will decrease by 40%.

- Outcome 2.2: By week 16, 70% of participants will report high feelings of self-efficacy in accessing needed treatment and self-care.

Goal 3: Increase social support.

- Outcome 3.1: By week 8, the number of participants who feel socially supported by their advisement counselor, staff from the health center, and peers from their advisement group will increase 40%.

- Outcome 3.2: By week 16, 80% of participants will report feeling socially supported by staff from the health center, and fellow participants.

Goal 4: Increase commitment to follow a wellness plan.

- Outcome 4.1 By week 8, the number of participants with chronic diseases not following a wellness plan will have decreased by 30%.

- Outcome 4.2: By week 16, 70% of participants with a chronic illness will be following a wellness plan.

Part 4: Evaluation Design and Measures

| Stakeholder | Role in Intervention | Evaluation Questions from Stakeholders | Effect no Stakeholder of a Successful Program | Effect on Stakeholder of an Unsuccessful Program |

| Adolescents | Participants served by the intervention | *Will the school-based health center staff be kind and welcoming? *If I go to the health center, will my friends be supportive? *Will I have to pay for services? *Will I feel better because I use the programs and services of the health center? *Will health lessons give me opportunities to talk to my friends? | *Increase in knowledge of services available at the school-based health center *Students with chronic illness will create and follow a disease management plan *Students will attend the school-based health center for acute care instead of making unnecessary visits to the emergency room | *Students will continue to have poorly controlled chronic diseases *If the clinic ultimately shuts down due to poor annual attendance, future uninsured students in the community or those lacking transportation will miss out on the opportunity to receive care |

| Parents/Families | Caretakers of the adolescent participants | *Will the health center save me money? Will the services be free to my child? *Will it be convenient for my child to visit the health center? *Will the health center collaborate with my primary care physician to get my child’s medical records? *Who are the professionals at the clinic? What kind of training do they have? *Will the health center violate my family’s privacy? *Will the clinic make my child feel better? | *The health center will accept all forms of health insurance and provide free Georgia Department of Public Health-funded treatment for all uninsured children. *Parents will be consulted about their children’s treatment and their wishes will be respected *Use of the health center will be convenient *Parents of children with chronic diseases or nutritional needs will be invited in to learn more about their child’s condition and to be involved win the creation of their child’s wellness plan z *Parents will be consulted before the creation of the health center so they have a chance in advance to express their wishes and ideas | *Parents will learn that their children are unable to have access to the health center due to lack of insurance *Parents will feel disrespected by the health clinic staff and parents who may already be distrustful of schools will have just one more reason to feel unwelcome at school *Parents will believe that the services they want most for their children are unavailable *Parents will fail to gain any new knowledge of how to help manage their child’s chronic condition |

| Principals/Teachers | Caretakers of the children who have other responsibilities and time needs other than the program | *Will the health center make our students feel better? *If our students are healthier, will their learning improve? *Will the health center decrease the spread of transmissible illness such as colds and influenza at the school? *Will my students’ absences decrease? *How much extra work will I have to do to support the program? *Will students receiving passes to the health center distract from my instruction? | *Students’ absences will decrease so grades will improve *The health center will provide minimal disruption to the school schedule *The school will see a reduction in the spread of transmissible diseases *Teachers will be able to focus more on instruction because the health center can provide the “nursing” that teachers often have to do | *The school will see zero reduction in absences *Transmission of infectious diseases such as colds, influenza, and pertussis will remain the same *Students needing to visit the health center during the day will disrupt class for all students |

| School Health Center Staff | The workers who will provide health services to children at the health center | *Will the students who actually need it most visit the health center? *Will the families trust us and let us serve their children? *How can we make the clinic emotionally and physically safe and inviting to adolescents? *How can we motivate students to want to get their well visits, vaccinations, and to follow a chronic disease management or nutrition plan? *Will the health center be effective in building wellness in adolescents? *How will be know we are having a positive impact our students’ health and wellness? | *Staff will feel motivated to increase participation in the health center programs *Staff will have confidence they are improving students’ lives *Staff will work to improve funding and to provide extra services students need | *No students will visit the health center and it will be unsuccessful *Staff will want to make changes so more children will attend *Staff will seek other jobs where, through increased success, they can increase their job security and enjoyment |

| Community Partners: Georgia Department of Public Health, local health department, local churches, YMCA, other non-profits | They can help provide funding and if desired implementation | *Will students with chronic diseases develop and follow a disease management plan? *Will enough students attend the health center to justify paying staff? *Will students living in poverty, those without insurance, and racial and ethnic minorities use the health center? (In other words, will it increase health equity by reaching the population for which it was intended?) *Will healthcare spending and rates of numbers of teenagers visiting the emergency room for non-emergency room use decrease? | *Community partners will be excited about the money saved by fewer emergency room visits and will want to continue funding and helping with the school-based health center *Community partners will be pleased with the percentage of students in the school community attending their yearly well-visits *Community partners will be pleased that students’ chronic diseases are under better control. | *Community partners will be frustrated that their resources were wasted *Community partners will be hesitant to invest any more money or time in the center *Community partners will lose confidence that school-based health centers work and will instead seek to invest their money with other organizations or programs |

Study Design and Threats to Internal Validity:

The study type we have chosen is a Quasi-Experimental study. Specifically, we will use the Comparison-Group Pre-Test/Post-Tests design. We chose this study type because of ethics. We are designing a program with the goal of it being a service to students. Ideally, it will have positive effects on children’s access and receipt of necessary medical treatment. Therefore, we don’t wish to deny this opportunity to any children if they and their families wish them to enroll.

In a true experimental study design, students will be randomly assigned to either the intervention or the control group. We will use the same design, only selection will be through voluntary enrollment. The control group will be all the other children in the school who chose not to enroll.

Our design can be diagrammed in the following way:

Intervention Group:

01 X 02 X 03

Control Group:

01 02 03

Participants in the intervention group will take a pretest during the first week of school. Then they will receive eight weeks of curriculum and take a formative test. After an additional eight weeks of treatment, the intervention group will take a post-test. The control group will only take the pretests. Since they and their parents chose to exempt the program they will not receive the intervention.

Potential Threat of Selection Bias:

The main threat to internal validity in this model is in selection bias. Although the students are from the same school as one another, it could be possible that some significant difference exists between the students if they and their parents self-select to participate in the program. Maybe personal health is a stronger personal value to them and so they have the outcome expectation that the program will be valuable and helpful. Maybe being a member of a different socioeconomic or minority group brings them to have more trust in health and school authorities. It could be possible that they have a chronic disease and so are more likely to believe that the program is necessary. Adding demographic information to our pretest could help us control for this potential threat. By adding questions about family income, number of visits to a clinic or pediatrician last year, number of emergency room and hospital visits last year, and race, we can determine if the intervention group is relatively similar to the control group or if significant differences exist.

Potential Threat of Contamination:

Another potential threat to the study design is potential contamination. First, there’s a possibility with almost any program that participants will tell their peers details concerning the curriculum, thereby potentially influencing them. This program is designed to increase social support. Specifically, students are encouraged to bring a trusted friend to the waiting room with them for moral support (if the participant desires and feels comfortable doing this). The invited friend may or may not be a participant in the study. However, as a consequence, his or her use of the health center and his or her management of chronic or acute diseases may increase. This has a positive impact on the child, school, and community. Therefore, it isn’t something it would be ethical to minimize.

A final potential threat is that of attrition. If lots of students drop out of the program, it makes it hard to tell if a difference exists between participants who remained compared to those who did not. Students who leave the study may be less concerned with their health and so less motivated to receive their well visits, for example. Students who remain may have been likely to have used the school-based health center with or without the treatment of the educational component. To reduce this risk, we plan to use

| Short-term or Intermediate Outcome Variables | Scale, Questionnaire, or Assessment | Brief Description of the Instrument | Example Item (for Surveys, Scales, or Questionnaires) | Reliability or Validity |

| Increase knowledge of services offered at SBHC & when they should be utilized | Barriers to Seeking Psychological Help Scale (BSPHS) | A 17-item self-reported scale to evaluate the barriers affecting students seeking psychological help. The SCS consists of 10 items and participants are asked to indicate to what extent they agree or disagree with each item on a five-point scale ranging from Strongly Disagree (1) to Strongly Agree (5). | “When a close friend of mine asked me opinions about his/her mental health difficulties, I can recommend him/her to seek psychological help.” | Reliability: 91 Validity: .74- .94 |

| Increase self-efficacy in attending wellness, acute care and chronic disease management appointments | Self-Efficacy about Leisure Time Physical Activity (SELPA) | The assessment was originally designed to assess perceptions of self-efficacy in young Iranian males regarding health planning, such as creating and following an exercise plan. (5-point likert scale: 1=absolutely correct to 5=absolutely incorrect) | I could follow a personal schedule for my health plan. | Reliability: .81 Validity: .79 |

| Increase in social support in visiting SBHC | Adolescent Health Attitude and Behavior Survey (AHABS) | The authors noticed a need for a survey with strong reliability and concept validity that measured risk behavior, attitudes toward sexual behavior and also wanted to concurrently assess youth protective factors. Each item is on a five-point scale ranging from Strongly Disagree (1) to Strongly Agree (5). | I would describe my satisfaction with my school experience as…. | Reliability: .78 Validity: .69- .85 |

Part 5: Process Evaluation and Data Collection Forms

Health and Wellness Program Student Enrollment Letter

Dear Parent/Guardian:

In partnership with Decatur School System, the state department of health and the Decatur Department of Health is conducting a health and wellness promotion program, and we are inviting your child to participate. During the advisement segment of the school day, students will visit the school-based health center for a tour of the facility. This will give them the opportunity to meet the staff members so they can feel more comfortable seeking medical care. They will also practice completing registration and appointment forms to learn how to schedule treatment.

Participants will receive curriculum regarding the services available in the health center and the need for chronic disease management. Activities will include videos, powerpoint presentations, class discussions, and short journals.

Students will take assessments at the beginning of the program, after eight weeks, and again at 16 weeks. In addition, students will be encouraged to visit the health center at least once per year for their wellness visits. As needed, students will create a health management plan and receive support in meeting wellness goals. All data will be confidential and only used for the purposes of improving the services offered by the school-based health center.

Please check all that apply:

_____My child has permission to participate in this program.

_____I prefer my child not participate in this program.

For more information regarding the program and the services offered by the school-based health center, please email: decaturschoolbasedhealthcenter@uga.edu

Today’s Date:________________________

Student Name:______________________

Student’s Date of Birth:______________________

Student’s Signature:________________________

Parent’s Signature:__________________________

Child’s Age:_______________________________

Child’s Grade:_____________________________

Child’s Homeroom/Advisement Teacher:_____________

Attrition:

Each student will be asked to provide the following information during the first advisement session of the year and to complete it again at the end of the school year to monitor program participation and attendance. School health center staff will record attendance at the beginning of each session. They will also note if a child lacked parental permission to participate in a potentially controversial aspect of the program (mental health awareness, sexual risk reduction, etc.) and the child was excused for supervision in the media center.

School-Based Health Center Wellness Program:

Contact Information Form

Name:_____________________

Date of Birth:________________

School Name:________________

Student’s Race:_______________

Student’s Ethnicity:___________

Health Insurance (Yes/No)

*If yes, type of insurance

Home Address:____________________

Parent/Legal Guardian Name:____________________________

Home Phone:____________________________

Cell Phone:__________________________

Do you plan on moving or changing school enrollment any time during the school year? _________________________

| FIDELITY: 0-20% 21-40% 41-60% 61-80% 81-100% 1) What percentage of participants visited the school-based health center for a tour? ______________________________ 2) What percentage of participants practiced completing mock registration paperwork and appointment request forms? ____________________________________ 3) What percentage of participants watched the video on chronic disease management and participated in the discussion? ________________________________ 4) What percentage of participants wrote a journal about their ideas for chronic disease management (either for themselves if they have a chronic disease or for a loved one or acquaintance if not)? ll _______________________________________ 5) What was the level of engagement during class discussions? ________________________________________ 6) What percentage of participants brought a friend to their wellness, acute, or disease management visits? _________________________________________ 7) What percentage of participants attended their wellness visits? _________________________________________ 8) What percentage of participants with chronic diseases worked with clinic staff to create and follow a disease management plan? _______________________________________ |

References

Lamorte, W. (2018). The Social Cognitive Theory. Boston: Boston University. Retrieved on May 27, 2019, from

Vinney, C. (2019). Social Cognitive Theory: How We Learn From the Behavior of Others. Thought Co. Electronic Version Retrieved on May 27, 2019, from https://www.thoughtco.com/social-cognitive-theory-4174567

Georgia Health Equity Initiative (2008). Health Disparities Report: A County-Level Look at Health Outcomes for Minorities in Georgia. Georgia: Georgia Department of Community Health. Retrieved on May 27, 2019, from

Center for Innovation in Teaching and Learning (2013). Validity in Quasi-Experimental Research. Research Ready. Electronic Access on June 5, 2019, at https://cirt.gcu.edu/research/developmentresources/research_ready/quasiexperimental/validity

Abasi, M., Eslami, A., Rakhshani, F. & Shiri, M. (2016). A Self-Efficacy Questionnaire regarding leisure time physical activity: Psychometric properties among Iranian Male adolescents. Iran J Nurse Midwifery Resource, 21 (1): 20-28.

Bukenya, R., Ahmed, A., Andrade, J., Grigsby-Toussaint, D., Muyonga, J. & Andrade, J. (2017). Nutrients 2017( 9) 172.

Reininger, B., Evans, A., Griffin, S., Valois, R., Vincent, M., Parra-Medina, D., Taylor, D. & Zullig, K. (2003). Development of a youth survey to measure risk behaviors, attitudes and assets: examining multiple influences. Health Education Research Theory and Practice. 18 (4): 461-476.