Part I: Community Guide Update and Rationale for Intervention

| Author and Year | Intervention, Setting, Description, and Comparison Group(s) | Study Population Description and Sample Size | Effect Measure (Variables) | Results including Test Statistics and Significance | Follow-up Time |

| Bauer, et al., 2018 | This study sought to understand the effect of twice-daily text messaging for patients with pDPN in a large, integrated hospital system. Patients with painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy (pDPN) were recruited from a large health system to participate in a randomized controlled trials. Participants were selected for one of two groups, usual care (control group) or an intervention group with twice-daily text messages. | Patients were recruited from a large health care system, composed of 4 hospitals, 100 outpatient centers, and 25 primary care offices. Patients all received care at the health care system. 69 patients were recruited, 40 randomized to the intervention group with text messaging and 29 to the control group only with usual care. | Outcome was measured by the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale to measure medication adherence. MMAS was measured out of 4 points. | The intervention group had an MMAS of .9 (SD 1.1) and control group had MMAS of 1.4 (SD 1.2). There was no statistically difference between the two groups (p-value of 0.75). Text messaging did not improve medication adherence for pDPN patients in this study. | There was a follow up 6 months after an initial baseline. |

| Buis, et al., 2017 | This study sought to understand the effect of text messaging to improve hypertension medication adherence for African American patients. The researchers conducted two parallel, unblinded randomized controlled trials with patients with uncontrolled hypertension. Participants were selected for one of two groups: usual care (control group) or text messaging intervention for one month. | Patients were recruited from primary care and emergency departments. 58 primary care and 65 emergency department patients were recruited, with 53 primary care and 57 emergency department patients retained. Patients were randomized to two groups, one with usual care and other with one-month BPMED text-messaging intervention. From the primary care patients, 27 were in the intervention group, and 26 in the control group. From the emergency department group, 30 were in the emergency department group and 27 were in the control group. | The Morisky Medication Adherence Scale was used to measure medication adherence. MMAS is self-reported and is scored out of 8. | The intervention group improved MMAS score by 0.9 (SD 2.0), while the control group improved by MMAS of .5 (SD 1.5). This was an insignificant difference, with a p-value of 0.26. Medication adherence did not improve for intervention group in this study. | There was a one-month follow up to assess the effect of the intervention on medication adherence. |

| Ting, et al., 2012 | This study sought to understand the effect of text messaging on adherence to HCQ, a medication for childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematous. For the 14-month intervention, the cohort of patients with the chronic disease was split into two groups, one which received text messages prior to each scheduled HCQ dose, and another receiving standard education about HCQ. (control group). | The study included 41 patients with childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematous across two groups. One group of 22 patients received standard education regarding HCQ, and 19 patients received the text messaging intervention. | Three variables, pharmacy refill information, self-report of adherence, and HCQ blood levels were the effect variables to measure medication adherence. | Text messaging did NOT influence medication adherence to HCQ (p-value > .05), while the intervention did improve adherence to medical visits. At the beginning, 32% were sufficiently adherent, and there was an insignificant change to this measure after the 14-month follow up. | There was a 14-month follow up to evaluate medication adherence to HCQ. |

The Community Guide (2017) recommends with sufficient evidence that “the use of text messaging interventions to increase medication adherence among patients with chronic medical conditions.” Using the Thakkar, et al. (2016) systemic review based on 16 randomized controlled trials, sufficient evidence was found to support the use of a text-messaging intervention to increase medication adherence for individuals with at least one chronic condition. In summary, between the 16 studies utilized, patients in the intervention groups were 2.11 times more likely to adhere to their medication. Studies differed in geographic extent, so within high-income countries, intervention led to 13.8% increase in medication adherence compared to the control group.

After reviewing three recent studies, there is insufficient evidence to make a recommendation for or against the use of text-messaging interventions to increase medication adherence for patients with chronic illnesses.

This is due to the studies in the Community Guide (2017) all suggesting there is sufficient evidence of the intervention increasing medication adherence, but the three studies indicate that the intervention groups had no statistical difference from the control groups, suggesting there is insufficient evidence of the effect of the intervention. Due to conflicting results, the recommendations from the Community Guide should be revisited with a more thorough systematic review of more current research. All three of the studies were more recent than the systematic review and showed no reason to support the intervention effect. For example, the Buis (2017) intervention focused on the African American community of patients facing hypertension, a chronic condition. in this intervention, the intervention group improved MMAS score by .9 while the control group improved by .5, no statistical difference. The conclusion of this study was that text-messaging -webkit-standardintervention had no effect on medication adherence. For the Ting (2012) study, after a 14-month follow-up, the intervention group had no difference from the control group in medication adherence to HCQ.

This difference may be due to changes in technology since the publishing of the Community Guide. Most of the studies in the guide were conducted prior to smart-phone technology. This technology is rapidly evolving and may effect medication adherence differently today. Additionally, there is not consistency in where patients are acquired across all the studies and how medication adherence is measured. In the Ting (2012), Bauer (2018), and Buis (2017) studies, MMAS is the self-reported tool used to measure medication adherence, while in the guide, studies defined medication adherence by different measures. Hopefully, in the future, consistent research can be conducted to elucidate the true effect of text-messaging intervention on medication adherence for patients with chronic conditions.

Part II: Theoretical Framework/Model

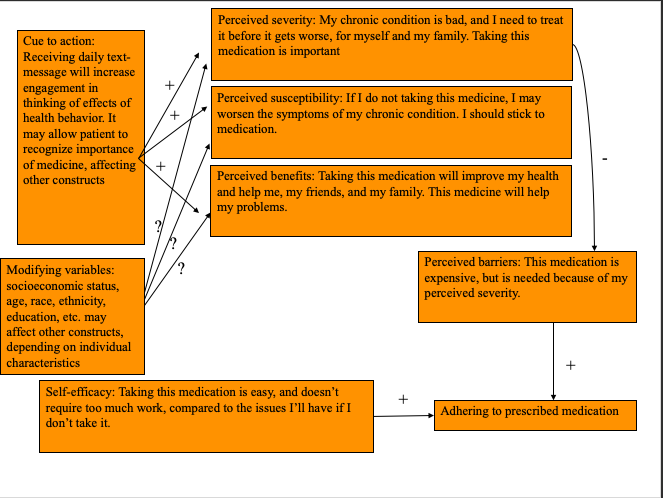

The health belief model (HBM) suggests that people’s beliefs and actions regarding their health explain how engaged they are with health-promoting behavior. The model also believes that a cue to action is required to prompt health-promoting behavior. This model works well to explain how a text-messaging intervention can increase medication adherence for patients with chronic illnesses. The model specifies six constructs: perceived severity, perceived susceptibility, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, self-efficacy, and cue to action. Through the text-messaging intervention, if we can affect their perception of engaging in the positive health-behavior, we can improve medication adherence. By making individuals think about how taking their medication regularly can impact their health, susceptibility to health problems, and how they are in control of their health, individuals are more likely to take personal agency and improve medication adhernece. Individual constructs are discussed here.

Constructs

Perceived severity: Perceived severity is the idea that the patient’s chronic illness has severe consequences. They believe that their health outcomes may become worse if not treated properly. Individuals need to understand the magnitude of their problems for any intervention to be effective.

Perceived susceptibility:Perceived susceptibility is the belief that the individual is susceptible to poor health outcomes. Their chronic illness needs to be treated through proper maintenance, or they will be susceptible to issues. By understanding that they are at risk, they are risk-averse, so they will take proper steps to improving their health.

Perceived benefits: By taking the medication, individuals are improving their health and know they are taking control of their chronic condition. Through the text-messaging intervention, individuals may understand how they may benefit from adhering to their medication, increasing the perceived benefits.

Perceived barriers: To improve their health, individuals have to take certain actions, but these may have consequences. By taking medication, they are taking on a financial risk that may make them less likely to take the medication frequently.

Modifying variables: Individuals all have different backgrounds and different individual characteristics. Someone’s personal history, family or demographic, may affect how the intervention is effective. The text-messaging intervention may be more effective on youth who are more akin to technology, but may be less effective on elderly. This needs to be researched to study the effect of the intervention on different populations.

Cues to action: This is one of the most important parts of the model. Without a cue to action, individuals will maintain their state of behavior. Through the text-messaging intervention, we psychologically are making individuals think about their illness and how they can effect change themselves. This is a pivotal part of the model in improving medication adherence.

Self-efficacy: This refers to an individuals’ perception of their ability to change their behavior and improve their own health. Through the text-messaging intervention, individuals will realize that they are in control of their health and can easily control it through their medication.

Outcomes

The above constructs clearly show how a text-messaging intervention can lead to engagement in the health promoting behavior. Through the text-messaging intervention, we are psychologically triggering individuals to adhere to their medication. Individuals will take personal agency to improve their health, because they believe they are in control of it and that their health can be improved through taking their medication. The feedback interaction is discussed further in the diagram of the conceptual model below.

The health belief model (HBM) suggests that people’s beliefs and actions regarding their health explain how engaged they are with health-promoting behavior. The model also believes that a cue to action is required to prompt health-promoting behavior. This model works well to explain how a text-messaging intervention can increase medication adherence for patients with chronic illnesses. The model specifies six constructs: perceived severity, perceived susceptibility, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, self-efficacy, and cue to action. Through the intervention, if we can affect their perception of engaging in the positive health-behavior, we can

Part III: Logic Model, Causal and Intervention Hypotheses, and Intervention Strategies

The target population for this text-messaging intervention is patients with chronic disease at the Northeast Cobb County VA Clinic. Veterans experience disproportionate rates of suicide, addiction, mental health issues, substance use disorders, PTSD, and trauma compared to civilians (Olenick, 2015). These risk factors and unique issues, compared to other communities, show how they are a health disparate group. Combined with chronic diseases, the veterans in this target population are an important group to understand how a text-messaging intervention can affect medication adherence.

We will seek patients at the clinic who have at least one chronic medical condition to enroll in a study to understand the effect of text-messaging intervention on medication adherence. Although the community is diverse and each individual has unique modifying variables, this will be an opportunity to understand how different communities are impacted by the intervention.

| Intervention Method | Alignment with Theory | Intervention Strategy |

| Expand knowledge of effects of medication, medication adherence, and failure to take medicine as prescribed | This intervention method targets the perceived severity, susceptibility, and benefits constructs. By expanding knowledge, individuals will understand the severe consequences of their chronic illness. They will also understand how to properly treat their ailment and the benefits of health-promoting behavior. | Text-messaging systems can be created to send daily or weekly facts to individuals enrolled. These can be facts on their medication and how medication adherence is important. |

| Increase self-efficacy | This targets the self-efficacy construct of the model. By changing their beliefs to control their own health, individuals are more likely to take matters into their own hands, take the medicine, and improve their health. Self-efficacy is important for this model to succeed, because while there are texts, as the intervention is designed, these texts must encourage individuals to actually engage in health-promoting behavior. | Text-messaging intervention can provide daily reminders asking if patients have taken medicine. Eventually, patients may take medicine before texts to feel accomplished or proud. Another strategy is a text-messaging weekly intervention that allows individuals to reflect on the past week and how they engaged in medication adherence and other health-promoting behavior. |

| Encourage participation in health-promoting behavior through motivation, support, and examples | This intervention method targets the perceived barriers construct of the health belief model. Through a text-messaging intervention, individuals can understand how other individuals suffer and treat their chronic illness. They can empathize with each other and realize they are not alone. They can learn from other’s examples. Additionally, texts can motivate people that their barriers are not insurmountable. | Enroll individuals in a weekly text-messaging system that provides examples of other patient stories and motivational support. This can be inspirational quotes, stories, or personalized messages from family. |

| Increase social support through a reminder system | This addresses the perceived barriers construct of the health belief model. Many may think that one of the main barriers is the regular consumption of medication and staying on schedule. With reminders, this removes a barrier of remembering to take care of one’s self as the cue to action will encourage the health-promoting behavior to take place. | Enroll chronic disease patients in a daily text-messaging reminder system that lets them know when to take their medication. |

| Input/Resources | Activities | Outputs | Short-term Outcomes | Intermediate Outcomes | Long-term Outcomes |

| Funding for text-messaging/app development and smartphones for all individuals participating in study The Community Guide research will guide this intervention and future interventions Partnership with the local Veterans Affairs clinic Partnership with a local electronics company or national mobile company (Apple/T-Mobile/Samsung) Individuals to manage text-messaging system and evaluation Grant to pay part-time managers | Week long planning session with intervention managers and administration Training day for volunteers/evaluators Recruitment week at the Veterans Clinic Training day for veterans with chronic conditions selected for intervention on smartphone usage. Daily text-message reminders for individuals in intervention groups Self-monitoring of the effects of the text-messaging intervention Self-monitoring of individual medication adherence Debrief meeting at the end of the intervention period with all patients. | Each intervention group and control group will have at least 30 veterans who qualify for the study Four managers will be trained to send weekly/daily text messages and coordinate with volunteers For every 5 patients, 1 volunteer will help train individuals on how to use smartphones during training day. 1000 flyers will be printed and handed out to the clinic to recruit individuals All volunteers will be recruited from local high schools and colleges. All managers will be paid part-time | Evidence of knowledge of the effects of medication, medication adherence, and failure to take medicine as prescribed. Evidence of positive social skills and depending on family and friends for support. Increase in self-efficacy. | Increased engagement in health-promoting behavior: Increase the number of veterans who regularly adhere to their medication for their chronic condition. Increase in utilization of medical information regarding their medication. | The long-term outcomes include: improved effectiveness of medication, improved health outcomes for their chronic illnesses, engagement in doctor-patient relationship to understand their health, improved mental health, improved self-efficacy |

Intervention Hypotheses:

- Week long planning session with intervention managers and administration will contribute to increased knowledge for participants of medication and medication adherence for the participants.

- Training day for volunteers/evaluators will contribute to increased knowledge for participants of the effects of medication, medication adherence, and failure to take medicine.

- Recruitment week at the Veterans Clinic will allow the intervention to find participants for the study, in hopes of increasing their knowledge and self-efficacy.

- Training day for veterans with chronic conditions selected for intervention on smartphone usage will ensure the effectiveness of the intervention delivery mode and will increase self-efficacy

- Daily text-message reminders for individuals in intervention groups will increase engagement in health-promoting behavior and increase participants’ knowledge of medication, medication adherence, and other relevant information.

- Self-monitoring of the effects of the text-messaging intervention improves participants’ self-management skills and will increase self-efficacy for the participants.

- Self-monitoring of individual medication adherencewill increase self-efficacy and increase willingness to increase social support and dependency on family and friends for emotional support.

- Debrief meeting at the end of the intervention period with all the patients will increase social support and increase knowledge of medication adherence and how to engage in health-promoting behavior and will encourage social support.

Causal Hypotheses:

- Increases in knowledge of the effects of medication, medication adherence, and failure to take medicine as prescribed will increase medication adherence, self-efficacy, and encourage health-promoting behavior, improving the health outcomes for affected individuals.

- Increased dependency on family and friends for emotional support will increase the perceived benefits of improving personal health, increasing self efficacy and engagement in health-promoting behavior.

- Increase in self-efficacy will increase medication adherence and increase self-monitoring of individual health.

- Increase in health-promoting behavior will increase medication adherence and improve health outcomes for individuals with chronic conditions.

Outcome Objectives:

Goal 1: Evidence of knowledge of the effects of medication, medication adherence, and failure to take medicine as prescribed.

- Outcome Objective 1.1: 80% of participants will correctly identify the effect of medication they are taking at the end of the 6-month intervention.

- Outcome Objective 1.2: 80% of participants will list two side effects of failing to adhere to medication at the end of the 6-month intervention.

Outcome Objective 1.3: 90% of participants will understand the severity of their chronic illness and understand how to treat it with health-promoting behavior at the end of the 6-month intervention.

Goal 2: Evidence of positive social skills and depending on family and friends for support.

- Outcome Objective 2.1: 70% of participants will self-report increased communication with family and friends regarding chronic illness 3 months into the 6-month intervention. This will be done through an evaluation with the participants’ managers.

- Outcome Objective 2.2: 70% of participants will self-report increases in mental health by the end of the 6-month intervention. The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) is a common public resource used for this goal of measuring mental health (Lowe, et al., 2004).

Goal 3: Increase in self-efficacy.

- Outcome Objective 3.1: 70% of participants will report increases in time management and self-evaluation 3 months into the 6-month intervention. This will be measured using the SEAMS scale which measures self-efficacy for medication adherence for patients with chronic conditions (See Measures Table in Part IV).

- Outcome Objective 3.2: 50% of participants will report taking medication before receiving daily text-messaging intervention by the end of the 6-month intervention. This data will be collected at the weekly evaluations with managers.

Goal 4: Increase in health-promoting behavior.

- Outcome Objective 4.1: 70% of individuals will report feeling better by 3 months into the 6-month intervention.

- Outcome Objective 4.2: 80% of individuals will self-report increases in medication adherence by the end of the 6-month intervention. The MMAS scale will be used to measure medication adherence (See Measures Table in Part IV).

Goal 5: Increase social support through a reminder system

- Outcome Objective 5.1: 50% of individuals will report taking the initiative to improve doctor-patient relationship in hopes of improving their personal health by the end of the 6-month intervention.

- Outcome Objective 5.2: 70% of individuals will report reaching out to a friend or family or other individual with similar health issues by 4 months into the 6-month intervention. The SSSS scale will be used to measure increased social support. (See Measures Table in Part IV).

Part IV: Evaluation Design and Measures

Stakeholders Table

| Stakeholder | Role in Intervention | Evaluation Questions from Stakeholder | Effect on Stakeholder of a Successful Program | Effect on Stakeholder of an Unsuccessful Program |

| Participants | Receive daily text-messages reminding participants to take medicine | How can I engage in health-promoting behavior? How will receiving daily text-messages improve my health outcomes? | Improved medication adherence and improved health regarding the chronic illness. Increase in self-efficacy and engagement in social support. | Participants may become overly dependent on text-messages and will not develop self-efficacy. Some participants may have no effect. |

| Family Members | Provide emotional support and encourage participants to engage in health-promoting behavior | How can I help my family member succeed outside of the intervention program? How will the intervention benefit the family member? How will this program affect the overall family? | Better health for family member. Knowledge of the effects of medication adherence, chronic illnesses, and health-promoting behavior. Understanding of family history given certain chronic illnesses. | Family members will lack engagement in participants’ health. Will oppose similar future interventions. Family members may not support participants emotionally. |

| Tech Companies/Grant Funding Entities | Provide the smartphones and funding for the intervention. Companies could utilize this research to develop apps and programs for customers. | Is the intervention effective? What is the validity of the research? How can we utilize this research for a greater population? | Participation in similar future interventions. Ability to use this research to fund further projects and create applications to help consumers maintaining overall health. | Loss of resources and may lack incentive to invest in programs that promote patient health and address issues with medication adherence. |

| Veterans Clinic | Provide primary care to participants in program. Benefit from participants increasing rates of medication adherence. | Is this program improving or decreasing the overall health of our patients? Does this intervention improve medication adherence? | Increased overall health outcomes by participants properly caring for their illnesses could lead to decreases in overutilization. | Waste of resources and patients may be overly-dependent on text-messaging intervention, so may lack ability to self-manage health or engage in health-promoting behavior, thus creating more work for clinic. |

The outcome evaluation design is a group randomized control trial using two treatment groups with a pre-test and two post-tests (3 months and 6 months into intervention). The intervention group will have 40 veterans who will receive training on how to utilize smartphones at a training day and will then receive daily text message reminders regarding medication adherence for their chronic illness. The control group will consist of 40 veterans who will not be receiving text messages from the intervention team. Both groups will receive the same initial training regarding why medication and medication adherence is important, but only the intervention group will receive additional training and intervention regarding the smartphones and text message reminder system.

Intervention Group: R O1 X O2 O3

Control Group: R O1 O2 O3

O1: Pre-intervention survey and evaluation at recruitment point

O2: Evaluation of veterans at 3-month point into 6-month intervention

O3: Evaluation of veterans at the end of the 6-month intervention

The veterans will be recruited from the Northeast Cobb County VA Clinic. After recruitment, participants will be randomly assigned into either the control or intervention group. An initial orientation will be given to all participants, regardless of group, covering basic educational materials, including medication, medication adherence, how to deal with chronic illnesses. A pre-test will be done at this time to evaluate how individuals believe their health to be and answer basic questions regarding their health status, self-report their believed medication adherence levels, and more, based on the outcomes and SMART goals. The test will measure: medication adherence (Goal 1), interaction with family, friends, and community (Goal 2), how individuals self-evaluate themselves (Goal 3), health status (Goal 4), and technology level (Goal 5). Then, the intervention group will alone receive their smartphones and training and registration for the text messaging service.

Threats to Internal Validity:

Selection Bias: Participants will have to express interest in participating in a study, so there is some self-selection of participants, even though participants are randomized into the control and intervention groups.

Self-reported Testing: The tool used for medication adherence for this intervention, the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS), is a self-reported tool, so this is not as accurate as an evaluator going to measure medication adherence. For this intervention, there is a trade-off between accurate measurement-taking and self-reported tools, due to the importance of self-efficacy in the health belief model.

Instrumentation: Based on the smartphone technology used, there may be differences in how effective each technology is in aiding in the intervention effectiveness. A flip phone may not be as effective as an Apple iPhone. Additionally, while the intervention will provide training on how to use the smartphones for the intervention group, differences in quality of training will effect intervention effectiveness.

Maturation: As patients age with their chronic illness, they may become better at taking care of their own health, so medication adherence may improve regardless of intervention. Additionally, the smartphones have other uses, so patients may be using the smartphones for other helpful purposes, introducing additional confounding variables. Because we are comparing the intervention group to the control group, both groups become better at taking care of their own health as time proceeds. To minimize the risk of the smartphone technology as a confounding variable, through evaluation, managers can understand how participants used the technology and how the smartphones affected the participants outside of the study.

Given these threats, the control group will not be exposed to the smartphone-training portion of the orientation, preventing other threats to internal validity. Additionally, the use of multiple evaluation points in the intervention period will allow for comparison over time analyses.

Measures Table

| Short-term or Intermediate Outcome Variable | Scale, Questionnaire, Assessment Method | Brief Description of Instrument | Example item (for surveys, scales, or questionnaires) | Reliability and/or Validity Description |

| Expand knowledge of effects of medication, medication adherence, and failure to take medicine as prescribed | Morisky Medication Adherence Scale-8 (MMAS) (Moon et al., 2017) | MMAS is the most widely used test to assess medication adherence for patients. The test is self-reported. MMAS-8 is based on 8 questions. The 8 questions can be found at the bottom of Form 2 on Part V of this paper under subheading Attrition.” The test requires individuals to self-assess their last week, which can lead to some errors in hindsight bias or failure to remember events correctly. | MMAS-8 Example survey questions: 1) Do you sometimes forget to take your medication? 2) Over the past week, were there any days you did not take your medication? 3) Have you ever purposely not taken your medication due to side effects or health status? 4) When you are travelling and/or out of the home frequently, do you forget your medication? 5) Did you take your medication yesterday? 6) Do you stop your medication when you believe your illness is under control? 7) Do you ever find it difficult to stick to your medication treatment schedule? 8) Do you often have difficulty taking your medication? How often? | In this systematic survey by Moon et al. (2017), 28 studies were analyzed to understand the effectiveness and validity of MMAS. Cronbach’s alpha: .67 Pooled test-retest correlation: .81 Pooled sensitivity: .43 Pooled specificity: .73 |

| Increase self-efficacy | Self-Efficacy for Appropriate Medication Use Scale (SEAMS) in Low-Literacy Patients With Chronic Disease (Risser et al., 2007). | Risser et al. (2017) sought to develop a self-efficacy scale for medication adherence for patients with chronic illness. The tool is appropriate for individuals of all literacy levels. SEAMS is a 13-question scale to estimate self-efficacy for medication adherence. | SEAMS example questionnaire: 1) Are you confident that you will make your appointments as scheduled? 2) Are you confident that you will be able to take your medication as directed. 3) Is it difficult to take medication when there are multiple different medication to take each day. | Cronbach’s alpha: .89 Construct validity: 52.3% of the variance in SEAMS is based on two factor loadings. Interitem correlation: .32 Test-retest reliability: .62 |

| Evidence of positive social skills and depending on increased social support | Social Support Satisfaction Scale (SSSS) (Heitzmann & Kaplan, 1988) | This scale is a short form containing a few questions concerning support resources, asking questions regarding how individuals will act in given scenarios. There is also a long form. | Survey questions: “When you are having diffulties with your chronic illness, do you have a person X you go to? How does person X make you feel?” | Long form Test-retest correlation: .96 Cronbach’s alpha: .93 Short form Test-retest correlation: .91 Cronbach’s alpha: .69 Interform Substitutability: .85 Validity data was not reported. |

Part V: Process Evaluation and Data Collection Forms

Recruitment/Enrollment:

Two forms are listed below to assist in recruiting volunteers and managers to administer the health intervention program and to recruit participants from the local VA clinic to participate in the study.

Participant Recruitment Form:

Recruiting Veterans at the Northeast Cobb County VA Clinic for a Health Promotion Program

The University of Georgia School of Public Health is conducting a research program at the Northeast Cobb County VA Clinic to understand the effects of technology on medication adherence for veterans with chronic illness. This program is recruiting veterans of any age to engage in this intervention to analyze how a text-messaging reminder system improves medication adherence and overall health status for veterans. All information will be private and your participation is 100% voluntary. Rest assured, while conducting research, our primary concern is your security and the security of your data. If you would like to participate, please fill out this form by August 1, 2019.

Name:

Date of Birth:

Address:

Email:

Phone Number:

Doctor:

Volunteer Recruitment Form:

Recruiting Volunteers for Help Health Promotion Program at Northeast Cobb County VA Clinic

The University of Georgia School of Public Health is conducting a research program at the Northeast Cobb County VA Clinic to understand the effects of technology on medication adherence for veterans with chronic illness. We are looking for volunteer students at the high school and college level to assist with training veterans on how to use smartphone technology. Volunteer service hours will be provided, and there are also four paid part-time positions available for college students as managers to assist in the administration of the research program over the next six months. If you are interested in assisting the cause, please email a copy of your resume and contact information to techintervention@uga.edu. If you have nay questions please contact us at 706-523-2393.

Sincerely,

Aditya Krishnaswamy

Health Promotion Student

University of Georgia School of Public Health

Attrition:

In addition to the two forms below, while building the text-messaging intervention, an application will be built into the texts to automatically notify managers if the participants have opened and read the text message. Without a paper trail, this technology plug-in will provide an accurate estimate of how many participants complete the intervention.

Participant Contact Information Form:

Every veteran will fill out the below contact form after being selected for the program. These forms will be processed using technology due to the security of health and private information. This form will also be updated after the conclusion of the 6-month intervention period.

Contact Information Form

| Name | |

| Participant ID (given at training day) | |

| Date of Birth | |

| Address | |

| Today’s Date | |

| Home Phone | |

| Cell Phone | |

| Family/Friend Point of Contact (PoC) | |

| PoC Phone | |

| PoC Email | |

| Doctor at theNortheast Cobb County VA Clinic | |

| Doctor’s Phone | |

| Doctor’s Email |

Weekly Evaluation of Medication Adherence

This form will be administered once a week by the managers of each of the veterans by phone call. If unavailable by phone call, managers are responsible for minimizing attrition. The questions are based on the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS) sourced from a 2015 article in the International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology by Cuevas and Peñata (see references for more information).

Weekly Evaluation Form

| Name | |

| Participant ID | |

| Week # | |

| Date | |

| Morisky Medication Adherence Scale Test Questions: Answer Yes/No to the next 8 questions. | |

| Do you sometimes forget to take your medication? | |

| Over the past week, were there any days you did not take your medication? | |

| Have you ever purposely not taken your medication due to side effects or health status? | |

| When you are travelling and/or out of the home frequently, do you forget your medication? | |

| Did you take your medication yesterday? | |

| Do you stop your medication when you believe your illness is under control? | |

| Do you ever find it difficult to stick to your medication treatment schedule? | |

| Do you often have difficulty taking your medication? How often? |

Fidelity of Program Checklist

How well was each component of the intervention program executed? Use the table below to indicate the level of efficacy (100-70%/70-40%/<40%) and expound upon your selection. Every manager will fill this out at the end of the 6-month intervention.

| Recruitment Components: | 100-70% | 70-40% | <40% |

| Was the recruitment of veterans consistent? | |||

| Were all forms completed by the veterans? | |||

| Training Components: | |||

| Were all the veterans trained consistently? | |||

| Were all the veterans in the intervention group trained on smartphone technology consistently? | |||

| Were there any technical difficulties affecting training? | |||

| Intervention Components: | |||

| Were managers sending out appropriate text messages to intervention group daily? | |||

| Were all veterans in intervention group able to use smartphones appropriately for duration of intervention period? | |||

| Were all veterans in intervention group opening text messages regularly? | |||

| Were all veterans in intervention and control groups filling out weekly medication adherence self-assessments? |

References

Bauer, V., Goodman, N., Lapin, B., Cooley, C., Wang, E., Craig, T. L., … & Masi, C. (2018). Text Messaging to Improve Disease Management in Patients With Painful Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy. The Diabetes Educator, 44(3), 237-248.

Buis, L., Hirzel, L., Dawood, R. M., Dawood, K. L., Nichols, L. P., Artinian, N. T., … & Mango, L. C. (2017). Text messaging to improve hypertension medication adherence in African Americans from primary care and emergency department settings: results from two randomized feasibility studies. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 5(2), e9.

De las Cuevas, C., & Peñate, W. (2015). Psychometric properties of the eight-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8) in a psychiatric outpatient setting. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 15(2), 121-129.

Heitzmann, C. A., & Kaplan, R. M. (1988). Assessment of methods for measuring social support. Health Psychology, 7(1), 75.

Löwe, B., Kroenke, K., Herzog, W., & Gräfe, K. (2004). Measuring depression outcome with a brief self-report instrument: sensitivity to change of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). Journal of affective disorders, 81(1), 61-66.

Moon, S. J., Lee, W. Y., Hwang, J. S., Hong, Y. P., & Morisky, D. E. (2017). Accuracy of a screening tool for medication adherence: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale-8. PloS one, 12(11), e0187139.

Olenick, M., Flowers, M., & Diaz, V. J. (2015). US veterans and their unique issues: enhancing health care professional awareness. Advances in medical education and practice, 6, 635.

Risser, J., Jacobson, T. A., & Kripalani, S. (2007). Development and psychometric evaluation of the Self-efficacy for Appropriate Medication Use Scale (SEAMS) in low-literacy patients with chronic disease. Journal of nursing measurement, 15(3), 203.

Ting, T. V., Kudalkar, D., Nelson, S., Cortina, S., Pendl, J., Budhani, S., … & Brunner, H. I. (2012). Usefulness of cellular text messaging for improving adherence among adolescents and young adults with systemic lupus erythematosus. The Journal of rheumatology, 39(1), 174-179.