For first-year Public Health major Aya Mansour, the idea of having her extended family come visit her in Athens was a dream she knows can’t become a reality anytime soon.

“As a Syrian who has family trying to leave Syria, this ban diminished my hopes of ever being able to see them again,” Mansour said, shaking her head at the idea of never seeing her 76-year-old grandmother again who’s been denied a visa on multiple occasions.

She’s referring to the executive orders on immigration issued by President Trump on Jan. 25 and March 6. The bans have interrupted the lives of those with student visas, those with family in the six countries on the banned list, and thousands more across the country.

The first executive order on immigration imposed a 90-day travel ban on seven countries – Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen – and denied all admission of Syrian refugees. The revised executive order, released in early March, removed Iraq from the list and put a 120-day hold on the Syrian refugee admissions program.

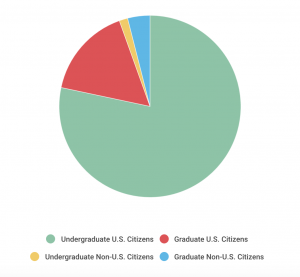

International students originate from 124 countries, four of which are on the banned list. Seven undergraduate students and 56 graduate are from Iran, and two graduate students are from Somalia and Sudan, respectively. Another undergraduate student is from Iraq, but the country has since been removed from the list of countries restricting temporary travel.

Although no University of Georgia students were immediately affected, many were troubled by the apparent lack of support from the administration and feared for future repercussions for their families. The university issued a statement following the first executive order on Jan. 25 to declare its intent to monitor the situation and provide assistance should anyone have questions or concerns. Other universities, such as the University of Michigan, issued statements saying it was against their policy to voluntarily share any information regarding the status of their international students. Only a subpoena would force them to do so.

The president of UGA, Jere Morehead, released a follow-up message after the school received backlash after the first statement was released to “express [his] strong and unwavering support for [the university’s] international faculty, staff, and students.” Unsatisfied, students, faculty, and local Athens community members spoke up against the executive orders by hosting a March for Immigrants on Feb. 3 from the Tate Plaza to the UGA Arch. Participants, such as fourth-year International Affairs major Mehreen Karim, said it’s “really about [her] community, not [her].”

But to some, statements and protests aren’t enough to erase their fears. Adnan Al-Atassi, a third-year Management and Information Systems major whose parents originate from Syria, said his friends and family are concerned for the future and the uncertainty the orders bring. As cited in the New York Times, “nearly 40 percent of colleges are reporting overall declines in applications from international students,” with the biggest decline coming from Middle Eastern countries. More graduate programs have seen a decline in applications than undergrad, a number that aligns with the University of Georgia’s 2-to-1 international graduates to undergraduates’ ratio.

“I have family who have canceled trips here because they are afraid of changes the administration will make while they are in the country,” Al-Atassi, who was born in Jeddah, said. “I also have friends overseas who were top of their class who are opting to go to Europe instead of going to school in the U.S.”

The ban, Al-Atassi continued, “alienates people.” And he’s right. The ban targets primarily Muslim-majority countries with no basis for its claims to protecting our national security. The countries on the list are not more likely to produce terrorism, as some may claim, than other countries around the globe. For example, the terrorists who hijacked the planes on September 11, 2001 were from Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and the United Arab Emirates, none of which are on the list for the travel ban.

First-year Biology major Linda Sghayyer agrees. In a short documentary titled “Dear Mr. President: What Muslim Youth Want President Trump to Know,” Sghayyer talks about how banning Muslims overseas doesn’t only affect them, but the Muslim community as a whole and the impact it has on families.

“By banning some Muslims from coming here, you’re like, not only affecting them, you’re affecting us,” Sghayyer said. “Imagine if you could not see your daughter because of your religion.”

Luqman Elrifadi, a first-year International Affairs major with dual Libyan and American citizenship, said he and his brother may not be here had their parents immigrated sooner from Libya.

“My parents were accepted into America in the ‘90s as political refugees,” Elrifadi said. He took it as a “personal insult” not only to himself but to his extended family and “all oppressed peoples who found safety and security in America.”

Even before the orders were issued, students were reported by The Intercept to have had their student visas revoked after traveling abroad over the winter break. More than 16,600 students in the U.S. were affected by the ban, according to the the Institute of International Education. Many were unable to board flights back home after trips and others were detained in airports upon their arrivals. More than 100 cases had been filed around the world a day after the ban went into effect, News Week reported. Hundreds of lawyers signed up with agencies across the country to volunteer their time and services to aid the thousands affected by the ban and hundreds more showed up on their own accord to provide pro bono services.

College is tough enough without the impending fear of being barred from re-entry into a country one may temporarily call home. The temporary blocks on the bans may be effective for the time being, but if another executive order is issued or the timespan for the block is up, there’s no telling what may lay in store for students, travelers, refugees, and hundreds of thousand innocent civilians looking to come across our borders.

“This is the land of peace and freedom,” Mansour stated. But with this ban, she concluded, clearly we’ve “been proven wrong.”