Mykaela Adams

ENGL 3050

TR 11:00-12:15

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, William Cullen Bryant, John Greenleaf Whittier, James Russell Lowell, and Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. (and sometimes, Ralph Waldo Emerson) wrote the ultimate Burn Book of Poetry for a contemporary audience. They didn’t write their poetry for other poets, they were too cool for that; instead they wanted the common people to love their writing and worship them. This way they stayed on top of the social ladder while giving people a source of entertainment. Hence their group name. These men were called Fireside Poets because their poems were typically read around a fire for the entire family to enjoy. Also, their work was included in textbooks and their portraits were placed on school walls which helped them also earn the name Schoolroom Poets.

All of the poets had a knack for languages and a strong interest in literature and education. Additionally, their poetry focused on American politics and New England landscapes. They also wrote about their opposition for slavery and compassion for Native Americans. Their poetry was educational and focused on the values of their time such as honor, hard work, and personal responsibility. They also managed to translate classic poems in to more modern versions giving learners an introduction to high level reading. The Fireside Poets emphasized their desire to be the voice of the average American.

Ralph Waldo Emerson (yes, the middle name is uber important). If there’s ever a pillow case that has some sort of inspirational quote on it, chances are it was written by him (I would know because I have one). He was definitely the leader of the group. The Regina George of all Fireside poets. He was even one of the first in the group to be inducted to the Hall of Fame for Great Americans. He went out of his way to go against what the other group members did; he rejected the traditional European forms and instead used newer American forms that focused on content rather than form. So basically, he had some bomb poems, but his form was kind of trash. Let’s be honest now.

You can clearly see the superiority in his face

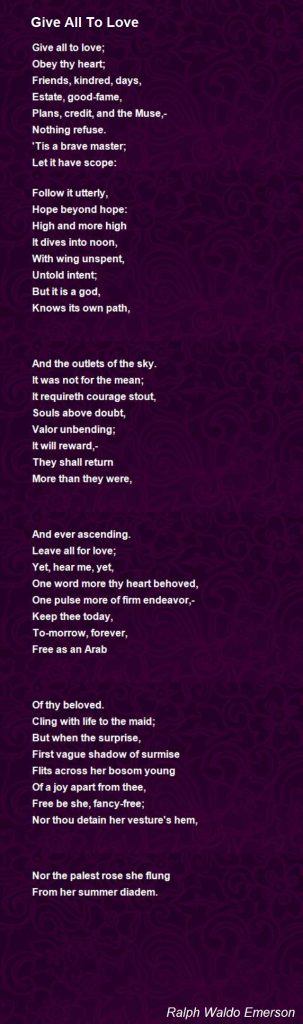

“I embrace the common, I explore and sit at the feet of the familiar, the low” (Emerson). Emerson focused on keeping the “lower people” happy with his work. Without the common people, these poets would have been just an afterthought and Emerson knew this, so he used this knowledge to the best of his abilities. An example of this is shown in Emerson’s poem Give All to Love. The word choice Emerson used was simple (there aren’t complex words in the poem and the punctuation is easy to follow), and the message he conveys is not hard to understand.

Give All to Love, Ralph Waldo Emerson

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, AKA Cady Heron, seriously, I mean it. He studied modern languages in Europe for three years, worked at Harvard in 1836, and published his first collection of poems by the age of thirty-two. In 1901, he, along with Emerson, was inducted as members in the Hall of Fame of Great Americans. He was so successful, that he has a bust in the Poet’s Corner in Westminster Abbey in London (he’s the only American to this date to have received such an honor). So basically, he was loved and appreciated (just as much as Emerson) in his prime, but after some time, many viewed him as just another poet. In the end, Emerson kept his fame and people sometimes critique the rhyming patterns of Longfellow’s work.

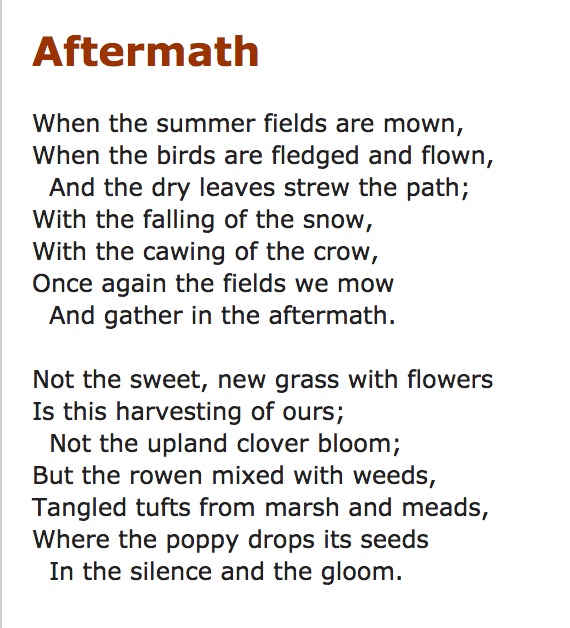

Aftermath, Henry Longfellow. The rhyming pattern Longfellow took on isn’t something you always see, but, once again, it isn’t a hard scheme to follow further showing how the Fireside Poets wrote for the common man.

The biggest feud the Fireside Poets had was with T.S Eliot and other emerging poets; the up and coming poets didn’t support America’s poetic past which included the Fireside Poets. Only thing is, all of the Fireside Poets were either dead or on their way out when Eliot was born. There wasn’t a single one of them left when Eliot and the other poets reached his prime. Eliot and the other poets were so intent on out shining the Fireside Poets, they tried to insult them when they couldn’t even defend themselves.

By the 20th century, the Fireside Poets’ fame started to fade. A new wave of poets came to claim the throne (like a Mean Girls sequel for poetry which, in my opinion, will never compare to the original), but anyways, the Fireside Poets were officially considered old and their poems were no longer in. But don’t get it twisted, they are still the original oldies but goodies of the poetry world.

Works Cited

A Brief Guide to the Fireside Poets. Academy of American Poets, 11 May 2004, https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/text/brief-guide-fireside-poets. Accessed 31 Jan. 2017.

Biography.com Editors. Oliver Wendell Holmes Biography. A&E Television Networks, 2 April 2014, http://www.biography.com/people/oliver-wendell-holmes-9342379#synopsis. Accessed 30 Jan. 2017.

Burt, Stephen. “When Pots Ruled the School.” American Literary History 20.3 (2008): 508-520. MLA International Bibliography. Web. 1 Feb. 2017

Give All to Love. Emerson, Ralph Waldo. Poetry Foundation. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems-and-poets/poems/detail/50464. Accessed 1 Feb. 2017

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Academy of American Poets, https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poet/henry-wadsworth-longfellow. Accessed 1 Feb. 2017.

James Russell Lowell. Academy of American Poets, https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poet/james-russell-lowell. Accessed 30 Jan. 2017.

John Greenleaf Whittier. Academy of American Poets, https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poet/john-greenleaf-whittier. Accessed 1 Feb. 2017.

Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth “Aftermath” Henry Wadsworth Longfellow [online resource], Maine Historical Society, http://www.hwlongfellow.org/poems_poem.php?pid=48. Accessed 10 Feb. 2017.

Ronan, K. “The Fireside Poets.” Michigan Quarterly Review 52.3 (n.d.): 332-343. Arts & Humanities Citation Index. Web. 1 Feb. 2017

William Cullen Bryant. Academy of American Poets, https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poet/william-cullen-bryant. Accessed 1 Feb. 2017.

so the whole matter was patched up through his agreement to confer with learned men, who might persuade him if they could. However, he wasn’t known as the most learned poet of the age for nothing and persuading him in any way was a daunting task not easily accomplished. It took six years for him to conform… yeah, six years.

so the whole matter was patched up through his agreement to confer with learned men, who might persuade him if they could. However, he wasn’t known as the most learned poet of the age for nothing and persuading him in any way was a daunting task not easily accomplished. It took six years for him to conform… yeah, six years.