Editor’s Note: This story originally published in December 2024 but was taken down due to a change in the 2024 Steve Spurrier Legend Coach of the Year Award recipient.

By: Olivia Sayer

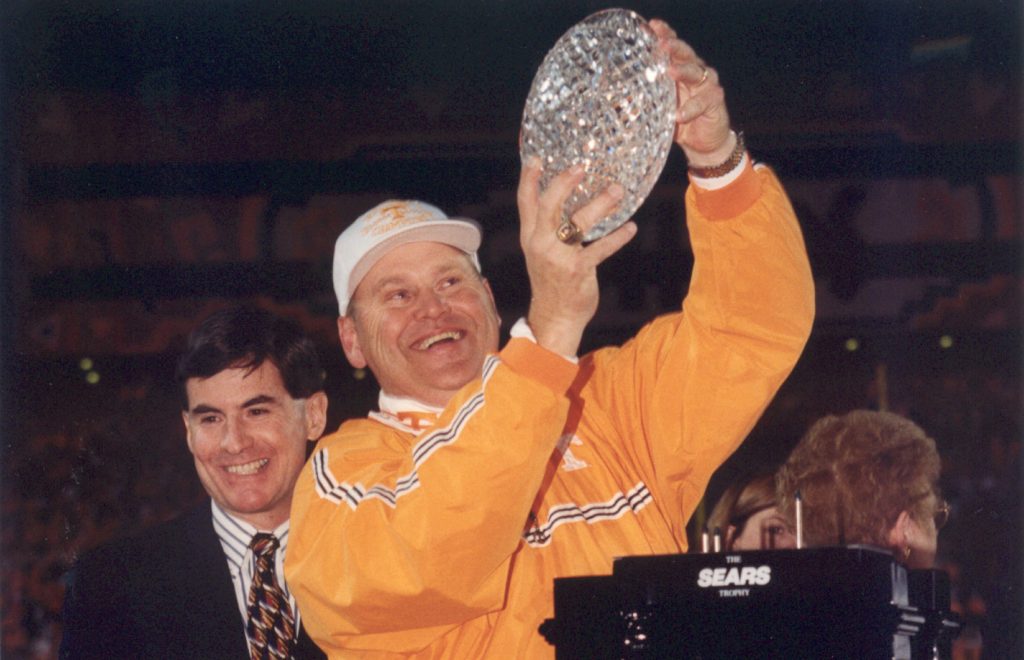

Phillip Fulmer hoists the BCS national championship trophy on Jan. 4, 1999 after defeating No. 2 Florida State 23-16 in the Fiesta Bowl. The win gave Tennessee its sixth national championship in program history and first since 1951. (Photo Courtesy/Tennessee Athletics)

It was bedlam.

A sea of orange flooded the field at Sun Devil Stadium as soon as the clock hit zero. With Rocky Top radiating from the instruments of the Pride of the Southland Band, players and fans celebrated Tennessee’s victory over No. 2 Florida State. The 23-16 win gave the Volunteers their sixth national championship in program history and first in almost 50 years.

Through the chaos, head coach Phillip Fulmer soaked in the moment. He felt the presence of his father James, who had passed away in June. A few minutes later, Fulmer hoisted the national championship trophy for a university he graduated from and a program he once played for.

Fulmer was named the 2024 Steve Spurrier Legend Coach of the Year Award winner on Thursday for his accomplishments and impact on college football. Spurrier said that Fulmer “did it the right way,” and his players “felt proud” to have him as their coach.

“He’s an excellent SEC coach and very deserving for this honor,” Spurrier said. “And I would consider him a good friend.”

Although they are now friends, Fulmer and Spurrier had no shortage of heated battles on the gridiron. During Fulmer’s 17-year span at Tennessee, his Volunteers and Spurrrier’s Gators combined for 12 SEC Eastern Division titles and seven SEC Championships.

“Usually whoever won the [Tennessee-Florida game] was going to represent the East in the SEC championship game,” Spurrier said.

Fulmer only won one BCS title with the Volunteers, but his teams likely would have excelled in the 12-team playoff. Tennessee finished in the AP Top 25 in all-but-four of his 17 seasons at the helm, with nine coming in the top-12 and three in the top-four.

He built his teams on a foundation of confidence, as the Volunteers believed they could line up against the game’s best and walk off the field victorious.

The spark igniting the orange flame

Before Tennessee’s 1998 national championship season, Fulmer had a stark message for his team. The Volunteers had graduated around 16 talented seniors — according to former safety Fred White — and Fulmer did not know if his new roster could compete.

“He told us we were an 8-4 team at-best,” White said. “I’ll never forget that meeting…you talk about lighting a fire under a group of people, that changed everything for us. And I think we became closer as a team because of that.”

Whether intentional or not — which White said is still up for debate — Fulmer’s comment sparked a fire within a Tennessee program that had not won a national championship since 1951. White said that there was no slacking, “and if you did, you were going to have a fight on your hands.”

Fulmer agreed that his team stepped up to the challenge.

“That team had a lot to prove,” Fulmer said. “I think everybody [was like] ‘they suck now’ because we’ve lost all these good players, and you could tell the players took the challenge way

early.”

Directly after Fulmer’s 8-4 comment, White said the team “kicked all of the coaches out” and called a players-only meeting. The Volunteers were player-led, according to defensive coordinator John Chavis, largely in part due to the culture Fulmer established.

“Our players knew what they had to do, and they held each other responsible for it,” Chavis said. “But really in a positive way…There were mistakes made, and they had to be out there to lift each other up when that happened, and they did a tremendous job of that.”

Built on belief

Former Tennessee head coach Phillip Fulmer speaks to his team. (Photo Courtesy/Tennessee Athletics)

Fulmer may have used a witty remark to motivate his team every now-and-then, but he also instilled confidence within it. However, he was not one to give an exuberant pre-game speech.

“I remember Coach Fulmer telling us one time before a game my freshman year, ‘I’m not a rara coach. If you’re looking for someone to get you up to play, you’re at the wrong school,” White said. “‘You came here to play in big games, and we prepared you to play in big games.’ I didn’t need a rara coach from that point forward.”

A prime example was the 1996 Citrus Bowl, when Tennessee faced No. 4 Ohio State in the two programs’ only meeting before Saturday night’s College Football Playoff matchup.

In 1995, both Tennessee and Ohio State finished their regular seasons 11-1 and had Heisman-caliber players – the names Peyton Manning and Eddie George might ring a bell — with stout defenses. However, not many outside of Knoxville, Tennessee picked the Volunteers to emerge as winners.

It was a different story between the walls of the visiting locker room in the Florida Citrus Bowl.

“We didn’t feel like any team in the country could beat us,” White said. “Because if you were one of the top teams in the SEC, there weren’t too many teams that could strap it up with you and put it down like that.”

The Volunteers limited Ohio State’s Heisman-winning running back to a season-low 89 yards rushing and forced three turnovers in the Buckeyes’ final four possessions to earn a 20-14 win. Chavis credited the team’s preparation and unwavering belief for its upset victory.

“Our kids had to understand that you don’t go onto the field unless you’re going to win,” Chavis said. “We didn’t work just to show up and play a game. We worked to win a game and be the best team on the field.”

Fulmer successfully portrayed his message of belief to the Volunteers because of his conviction. The former coach said he believed Tennessee “could win any game that we played,” and that confidence carried over to the players.

“When he talked about other teams, he talked about them in the manner of, there’s nobody we can’t beat,” White said. “And that confidence spread throughout the room. I never walked into a game thinking that we were going to lose.”

A relentless recruiter

Fulmer’s tenacity carried over to the recruiting trail, where he worked tirelessly to ensure the best players ended up in Tennessee orange. Shane Beamer, the current head coach of South Carolina, said that Fulmer was the “hardest working person in our football program” and called him a “relentless” recruiter.

“It didn’t matter where a player was, he was willing to go to them,” said Beamer, who worked as a graduate assistant under Fulmer from 2001-2003. “He was willing to do whatever it took to be able to bring players to Knoxville.”

“Whatever it took” included writing letters, spending countless hours on the phone and even walking through a garden in Griffin, Georgia with a recruit’s grandfather, despite wearing nice, clean shoes.

“[My grandfather] would always take the coaches to his garden to show off his garden,” White said. “And we would walk and see who kept walking with him.”

Some coaches stopped at the edge of the garden, while others paused a few feet into it. According to White, Fulmer walked the entire garden with his grandfather and never looked down to wipe off his shoes.

“I remember asking my grandfather, ‘Why would you take [him] into your garden? He has nice shoes on,’” White said. “And his response was, ‘He didn’t even bend down to wipe them off when he walked out of the garden. That man has character.’ From that point forward, every coach that came to visit, my grandfather made a point to tell them that Phillip Fulmer came by the house.”

Fulmer attributed his character and work-ethic to his parents. His dad worked two jobs, while his mom remained busy as a stay-at-home mother.

Shaping the future

Fulmer did not always have his sights set on coaching. When he graduated from Tennessee in 1972, the former offensive lineman considered going into law until Bill Battle sat him down for a conversation that Fulmer described as a “turning point” for him.

“He said they’d like to have me work as a graduate assistant, and I could think about what I wanted to do during that year,” Fulmer said. “But he thought I’d do a really good job as a coach, and it turned out that I loved that year.”

Phillip Fulmer smiles after a Tennessee football game. Fulmer retired with a 152-52 record, one national championship and two SEC championships. (Photo Courtesy/Tennessee Athletics)

Fulmer fell in love with coaching due to the impact it enabled him to have on young men. He enjoyed shaping them “from adolescence into manhood,” which is something he experienced first-hand from his former coaches.

“We do have a chance to make a difference in young guys’ lives like they did me,” Fulmer said.

The care Fulmer showed for his players helped foster a team-centered culture. He built an expectation of sacrifice in-practice that carried into games.

“If you weren’t willing to [sacrifice] a little bit in those situations, then you’re not going to be a great team player,” Chavis said. “And then if you’re not a great team player, certainly you’re not going to be a great individual player.”

Fulmer was not overbearing on his coaching staff either, as Beamer said he “allowed me to really grow.” White shared that Fulmer “orchestrated” the Volunteers but also “gave his coaches an opportunity to do their job.” The camaraderie within Tennessee’s coaching staff exuded onto the team.

“We spent a lot of time together as a staff,” Fulmer said. “Not just doing the X’s and O’s, but being there for the kids as they needed us.” And I think they knew that we cared, and it just perpetuated a good culture within the program.”

On the field, Fulmer prioritized building a fundamentally sound football team that could block, tackle and win its one-on-one battles. He was demanding but fair and always told players the truth. He also embraced coaching the program he was once captain of as a player.

“I was passionate about Tennessee doing well,” Fulmer said. “It’s home.”