By: Olivia Sayer

Former Michigan softball head coach Carol Hutchins on May 20, 2019 during Michigan’s NCAA regional game against James Madison. (Courtesy/Alec Cohen/Detroit Free Press)

Fifty-two years ago, one signature forever changed the trajectory of women’s sports.

Title IX, which was signed into law by President Richard Nixon on June 23, 1972, was created with the goal of providing equal access and opportunities for all students, regardless of their gender.

According to research conducted by Rutgers University, pre-Title IX, just 15% of college athletes were women. Now, 52 years after the law’s implementation, that number is up to 44%.

“Title IX is the reason we play today,” said Carol Hutchins, who retired from Michigan in 2022, as the winningest softball coach in NCAA history. “When somebody asks me, ‘Besides Title IX, what’s the most important thing that ever happened in women’s athletics?’ I can only tell you, ‘There is nothing.’”

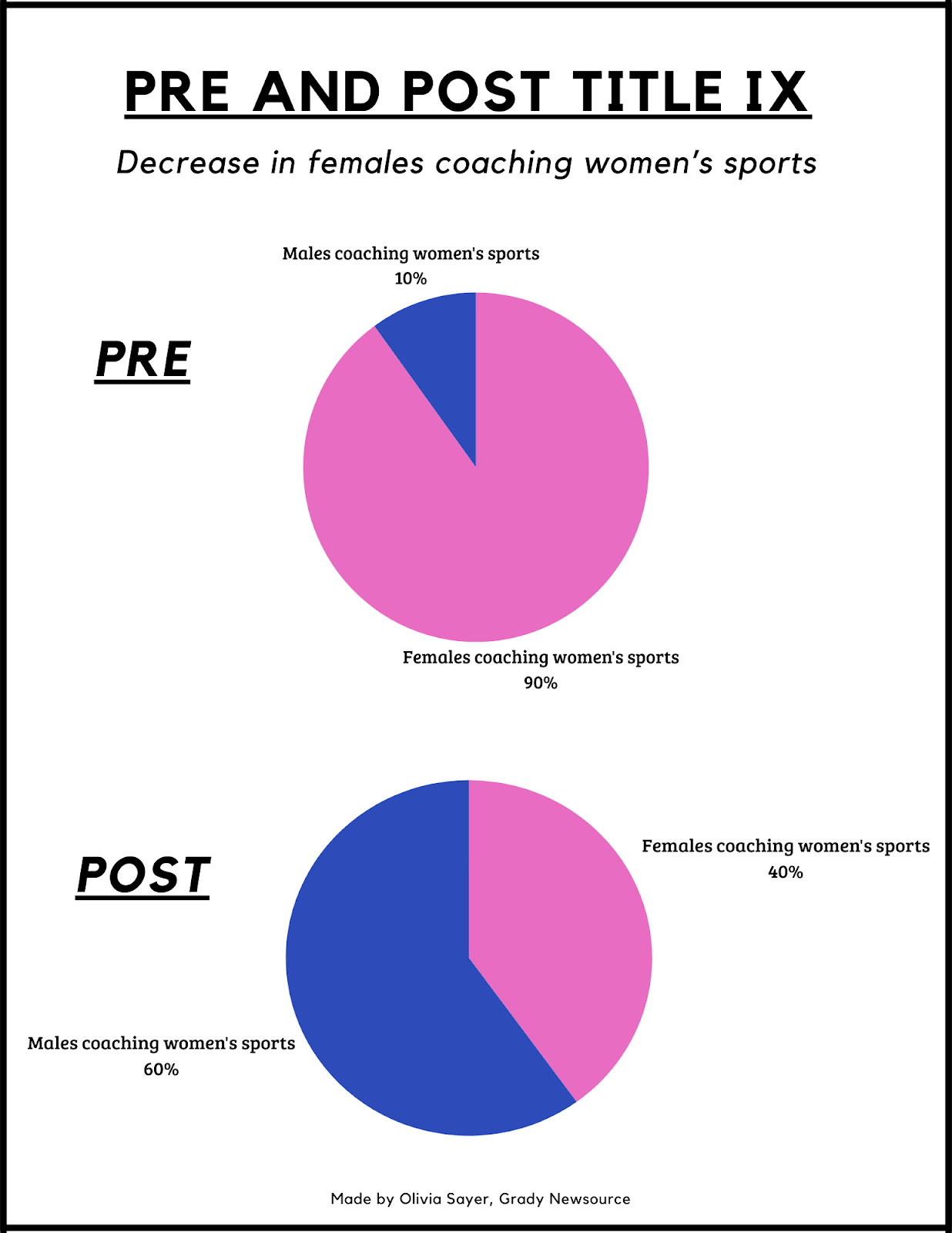

Although Title IX is one of the driving forces behind the success of women’s athletics today, it also has its costs. Since the law’s implementation in 1972, the number of female head coaches coaching female teams in college athletics has dropped more than 55%.

A coveted opportunity

Prior to Title IX’s implementation, coaching women’s sports was not a coveted position for males. According to research from the NCAA, the percentage of women’s teams with a female head coach in 1972 sat around 90%. Now, that number is around 40%.

Researcher and former college athlete Meredith Flaherty said that Title IX brought an aspect of “seriousness” to women’s sports, which made coaching female athletes a more coveted role.

“Once the NCAA opened up to be the governing body of women’s sport, and it got integrated as a more serious space through Title IX, jobs started to proliferate that had salaries and status attached to them,” Flaherty said. “As they increased in visibility and seriousness and pay, they became a space that men could step into and benefit from.”

Title IX required schools to provide athletic financial assistance that is proportional to their participation rates, which, in most cases, must reflect the ratio of the general student body.

“When that happened, things went up, resources got better [and] salaries got better,” Hutchins said. “And a lot of men realized, ‘Wow, this is a field I could coach in.’”

Marginalized jobs and growing stigmas

According to Flaherty, not only are women receiving fewer leadership positions, but they are also being “pigeonholed” into roles that require “taking care of the players” as assistants. This could mean their resumes do not appear as strong as their male counterparts applying for head coaching jobs.

“Women tend to get marginalized or pushed aside,” Flaherty said. “So even though women are getting jobs as assistant coaches in college sport, they aren’t translating to head coaching positions.”

This coupled with the stigma surrounding the ability of female head coaches — that they have less “inherent value, capability and ability” than males according to Flaherty — is not a recipe for success for females wanting to enter the coaching industry.

“Because of gender bias, people view men as more knowledgeable, as better leaders than women,” Hutchins said. “And the biggest problem I have with that is that too many women view it as that.”

Hutchins shared that she has heard female athletes say they would “like to play for a man,” further emphasizing the preexisting ideas surrounding male and female coaches.

“It’s like an unintended ‘ism,’ whether it’s racism, sexism, you name it,” Hutchins said. “It’s unintended because people think the way they think, and they do value men more. It’s just the way they are. And so when you bring to light the differences, it usually can be one of two things. One, it’s an ‘aha’ moment. Or two, it’s a ‘Really, now you’re complaining about this.’”

Flaherty, who is a youth sport researcher, attributed the stigma to the ideas enforced in youth sports. She said the “socialization” children experience in youth sports leads them to view male sports through a more “serious” lens.

“The socialization in youth sport that happens, teaches everybody involved in sport from a very young age that the boy sport is where it’s at,” Flaherty said. “That’s what’s more serious. That’s where the opportunity is.”

While the lack of female head coaches supports a sense of skepticism around them, a child’s doubt is not limited to one gender, according to Gillen Schecter, who is the head soccer coach at Clarke Central High School.

“Kids do not just assume that you know the topic you’re teaching anymore,” Schecter said. “So you really have to prove to them that even though I may not be the best player anymore, I still know the game really well. I think you have to earn their trust.”

Up to the athletes

So how does this preexisting idea change? According to Flaherty, it begins with organizational leadership amending their beliefs. If that does not work, a policy similar to Title IX could help drive change.

“Change occurs through legislation and people in positions of power in organizations making change that then can be seen by other organizations or other people in power and hopefully snowball,” Flaherty said. “Policy is one of the most key pieces of it because it sort of establishes what a practice baseline would be.”

In order to make a change, Hutchins believes, “the pressure needs to come from the student athletes.”

“Nobody gives a d*** about what coaches think,” Hutchins said. “They don’t care what we think, and if they don’t like what we say, they’ll fire us. The student athletes need to stick up for it.”

Hutchins, who now serves as Michigan’s special advisor to the athletic director, shared that reaching a “certain level of success” allowed her to fight for equality, since she had greater job security. However, she still believes student athletes can spark a change.

“I was compelled to fight for certain equality things when I knew that they couldn’t just turn around and fire me for lack of success,” Hutchins said. “When you reach a certain status or platform, you need to use your platform, and it needs to be the people that are affected by it, and those are student athletes. Student athletes have the power in college athletics. When student athletes speak up, they listen.”

Social Justice Statement: This story was created for a social justice journalism at the University of Georgia’s Grady College. To me, social justice journalism is shining light on topics that are often left in the shadows. It involves focusing on the people who are affected by these topics and giving them a voice.