By Kate Sims

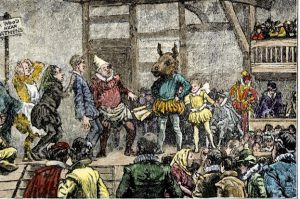

So, imagine: you’re a peasant sometime in the mid-1600s, and you’ve got an extra penny and some spare time. You could spend that penny on some extra food to make sure your kids don’t starve, but Willy Shakes is putting on a play pretty soon, and you’ve heard his stuff is good. Not, like, Marlowe good, but good. You put your penny in the box and get herded with all the other groundlings right in front of the stage. It’s hot, and you’re forced to stand, and the guy next to you (like RIGHT next to you, these people were packed in tight) smells kinda like fish, but before you can decide to cut your losses and head out, the play starts. And from act one, it captivates you. People descend from the sky, smoke creeps up through the floor, decapitated heads talk, thunder booms in the theatre though there’s not a cloud in the sky. One man stabs another, and blood bursts from his chest. People appear and disappear. Music plays, though there are no instruments visible. You go home and can’t stop talking about the amazing sights you saw that day.

Yeah, something like that.

To a common person in the 1600s, the special effects seen in theatres like The Globe and Blackfriars Playhouse would have been quite the sight to see. For your modern 21st century viewer? Not so much. Not when we’ve seen Dementors suck the souls out of people on the big screen.

What kind of special effects would you expect to see on an Elizabethan theatre’s—like the famous Globe Theatre’s—stage?

Stage + Set

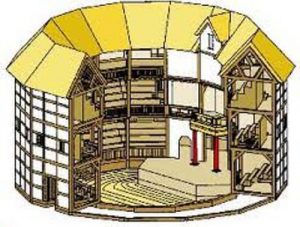

Theatre stages around this time were usually five feet off the ground, which left plenty of room underneath the stage for all sorts of fun tricks. With trapdoors, actors could disappear and reappear with ease or rise from the ground like a demon rising from Hell, which, consequently, is what they called it. The “Hell” part of the stage was also used for clothes changes and sometimes held musicians. Smoke could come out of the trapdoors, creating a misty scene or indicating magic was being used. Usually, the smoke was a mixture of different salts—depending on what color they wanted the smoke to be, limited to mostly red, black, yellow, or white—and alcohol, which was then burned.

On the flip side, “Heaven,” was comprised of false ceilings above the stage. From there, actors could be lowered by ropes to make dramatic entrances. Backgrounds could be raised and lowered for scene changes.

And check this out:

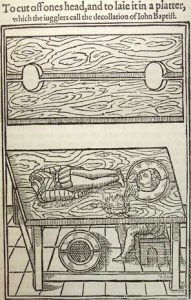

This diagram is of a trick probably used in Greene’s Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay. If you ever need to have a decapitated head talk, this is the way to do it! Without, you know, using actual magic.

Blood

Shakespeare’s plays were filled with all sorts of violence. Sword fights, suicides, stabbings. In order to display the gruesome deaths or wounds depicted, before the show, the actors cast lots to decide who in their troupe would actually get stabbed and die that night. Talk about dedication to the arts!

Just kidding.

For the most part, they used handkerchiefs soaked in animal blood to indicate a mortal wound. More ambitious troupes would fill a sheep or ox’s bladder with blood and hide it underneath the actor’s clothes so that when he got stabbed, it’d spurt blood everywhere. I don’t know about you guys, but I’d pay a penny to see that. (But think about the smell! Probably not worse than the guy standing next to you.)

Sound

Theatrical troupes also used sound effects to set the scene. Thunder could be simulated by rolling a cannonball across the floor or by waving a piece of sheet metal or by beating drums. Firecrackers sometimes went off to recreate battlefield noises or whenever a devil appeared (sound familiar?). To top it off, actual cannons would be fired during productions, usually when an important figure entered the scene or before a significant act.

And I’m sure you’re thinking: “Firecrackers? Cannons? In theatres built with wood and straw? I’m sure that never led to a horrible tragedy ever.”

Oh. Right.

On June 29, 1613, during Henry VIII, a cannon went off in the Globe Theatre, and a stray spark set the thatched roof on fire. The entire theatre burned down within two hours, with no recorded casualties. Although, there is an account of a man whose pants caught flame. Luckily, he had the idea to douse the flame with his bottle of ale. Yeah. We’re not really sure how that worked, either.

So, the next time you’re at a movie, and you hear an explosion, you can thank people like Phil Tippet and Greg Cannom. Because of them, your pants will not catch on fire.

Resources:

http://entertainmentguide.local.com/special-effects-theater-during-elizabethan-era-4056.html

http://www.bardstage.org/globe-theatre-special-effects.htm

http://www.bardstage.org/globe-theatre-fire.htm

http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/SLT/stage/staging/specialeffects.html

http://www.shakespearesglobe.com/uploads/files/2014/06/special_effects.pdf