By: Theresa Connolly

Literary figures produce works that change and shape us, works that make us consider new things and think deeply, works that transcend their time. It is easy to forget however, that the creators of these literary masterpieces were people themselves, who had troubles and life experiences all their own. Christopher Marlowe lived for only a short 29 years, but his contributions to English Literature have far outlasted his short lifespan. His revolutionary poetry and literary techniques make him a legend in the literary world. Yet, his life story was nothing short of legendary as well.

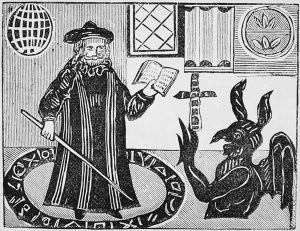

Christopher Marlowe was born to John and Catherine Marlowe in the year 1564. The exact date of his birth is unknown, but he was baptized on February 26th of that year. His father was a shoemaker, so Marlowe was not raised in nobility. Yet, he was very well educated as a youth, attending King’s school, and then receiving a scholarship for Corpus Christi College in Cambridge. He became a poet and playwright, creating works such as “The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus” and “The Jew of Malta”. These works, and his other pieces, were extremely popular, and earned reverence from the public, and Marlowe’s fellow scholars.

Though, Marlowe’s interesting exploits expand beyond just his literature. During his years at college, he was often absent for long periods of time, with little explanation. These absences were longer than the sanctioned times prescribed by the university, and sometimes, Marlowe disappeared for up to 32 weeks. Also, Marlowe was reported to have spent a lot of money on food and drinks at this time, more than he would have been able to afford with his scholarship.

The theory behind these strange actions is that Marlowe was secretly a spy. Marlowe is believed by many to have been a secret agent for Queen Elizabeth I. This theory, though seemingly outlandish, was further validated when Marlowe tried to apply to get his master’s degree. He was first denied, (as rumors had spread that he was a Catholic sympathizer) but was then granted his degree after the Queen’s privy council interceded. The privy council stated that Marlowe “had done her Majestie good service, & deserved to be rewarded for his faithfull dealinge….” (Poetry Foundation par. 2) He was then immediately granted his degree. So what was this “good service”? Many scholars believe that this service was Marlowe’s espionage in the name of the Queen.

Espionage was not Marlowe’s only life choice that was unorthodox for the time. He was also an atheist, and was most likely homosexual. In addition, he was mysteriously involved in two separate murders, though the circumstances of both are unknown.

The mystery shrouding his life also applied to his death, as many scholars are uncertain about the motives behind his murder.

The short story is this: Marlowe was out with some friends at a bar, when he became involved in a fight with a man named Ingram Frizer. The argument got heated, and Marlowe grabbed a knife, and stabbed Frizer. Frizer then retaliated by stabbing Marlowe above his right eye, killing him.

This story seems to be a simple one, yet, there are many theories to why Frizer killed Marlowe. A few weeks earlier, Marlowe had been arrested for suspicion of being an atheist. During a time of strong protestant religious fervor, this was an act of heresy. Yet, Marlowe was released soon after his arrest. And a few days after his acquittal, he was killed.

So, was it Elizabeth I who ordered his death? Many scholars and theorists say yes.

The fact that Marlowe had such a short yet turbulent life shows that his experience was great. Without such experience, he might not have been able to produce such well-constructed stories. If his life had been longer, and he had been able to go on more adventures, we can only imagine the kind of literature that he would have produced. If he had not died, he could have become even more famous and revered. If Christopher Marlowe had not been killed, the age that is marked by the contributions of Shakespeare might have been remembered as the age of Marlowe.

Further Resources:

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/3647398/Who-killed-Christopher-Marlowe.html

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems-and-poets/poets/detail/christopher-marlowe

http://www.britainexpress.com/History/bio/marlowe.htm

http://mentalfloss.com/article/80556/mysterious-death-christopher-marlowe

Citations

Black, Joseph. “Christopher Marlowe.” The Broadview Anthology of British Literature. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Pr, 2010. 402-03. Print.

Conradt, Stacy. “The Mysterious Death of Christopher Marlowe.” Mental Floss. Mentalfloss.com, 30 May 2016. Web. 05 Nov. 2016.

Feingold, Michael. “Street Fighting Man.” Nytimes.com. New York Times, 29 Jan. 2006. Web. 5 Nov. 2016.

Honan, Park. “Who Killed Christopher Marlowe?” The Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group, 21 Oct. 2006. Web. 06 Nov. 2016.

Poetry Foundation. “Christopher Marlowe.” Poetry Foundation. Poetry Foundation, 2016. Web. 06 Nov. 2016.

Ross, David. “Christopher Marlowe Biography.” Britain Express. Britainexpress.com, n.d. Web. 06 Nov. 2016.

Image Citations:

WordPress.com. Doctor Faustus. Digital image. WordPress.com. WordPress.com, n.d. Web. 6 Nov. 2016.

Christopher Marlowe Image. Digital image. Wikimedia.org. Wikipedia.org, n.d. Web. 6 Nov. 2016.