[written by undergraduates Alexandra Carlsrud and Abraham Johnson]

Throughout this past semester, our studies on medieval manuscripts have led us to some far-out places. We’ve learned the medieval techniques for crafting manuscripts, which led us to study the modern protocol for preserving these texts, all the way to pitching proposals for new library websites that house all of this information. The most interesting and unanticipated turn in our research, however, was the final portion of this class. For the last month, our cohort has delved into the chemical makeup of manuscript fragments. It took a while for that to sink in for even us studying the material, so maybe some explanation is needed.

Our class was divided into pairs and assigned random fragments from larger, originally unknown manuscripts. We took these pages and were told to come up with a justified backstory, complete with evidence. For some groups, this was easier than others. For our group, it meant hunching over our page with a magnifying glass trying to decipher gothic Latin text. Eventually, thanks to our handy friend Google, we were able to find our deciphering online. The text matched up perfectly with an old French Book of Hours from around 1300-1400, the Horae de Sanctu Spiritu. From here, the work was only uphill.

After we learned what our manuscript fragment generally was, it was time to dig deeper into its backstory. Dr. Alice Hunt, a scientist from the UGA Anthropology Department, came to our classroom to tell us we were going to become scientists too– at least, for the next few weeks. What followed was our introduction to a device called pXRF. This device basically reads the molecular composition of small source materials by focusing gamma rays on a site, which causes a small level of radiation to occur. From here, the pXRF reads the molecular aftereffect of the radiation, which allows specific elements to show up in the readings.

So, to put this science into context, our groups were asked to select several sites on our manuscript fragments that featured “pigmentation” (or “color”) to test in the pXRF process. By determining what these pigments were composed of, we would be able to answer some really important questions: Where did these pigments come from? Is that surprising in context to where these manuscripts are from? For our sites, we wanted to focus on four different shades of red pigment found on our page. We were eventually led us to a series of questions more focused around these sites:

- What pigments are the red shades made out of? Are they different? How so?

- How pure/clean are these pigments?

- Do the pigments suggest a class-level for the manuscript buyer?

These questions require an interdisciplinary appeal to the academic resources at UGA. We can absolutely look back at historical and anthropological records, but the solid evidence from the pXRF readings gives us a more solid ground to consider these pigments and therefore their manuscripts. With that knowledge, we went on to analyze our new information from the pXRF. Dr. Hunt helped us learn and use a program called “Artax” which interpreted the pXRF readings into graph form, allowing us to see what chemical elements the sites contained.

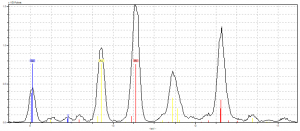

Our First Site: Red Initial Background

For our first analysis site, we analyzed a red initial background on our fragment. When we first looked at the spectra analysis, we identified a pretty messy group of elements: copper, lead, gold, calcium, and iron. Seeing that the parchment behind the pigment would yield iron and calcium, we narrowed down the pigment elements to copper, gold, and lead. This was confusing, mainly because there isn’t a red pigment that features these elements together. Our first assumption was that this was maybe a mixture of azurite and red lead. This would maybe explain the sort of purple tint in the red.

After consulting Dr. Hunt and Dr. Camp, we all agreed that this mystery needed a little more sleuthing. What could explain all these interacting elements? First, we looked at the surrounding designs on the page and found some explanation. There was some gold-leaf on a nearby design, as well as white pigments in the leaves– both of these would explain the traces of lead and gold in our pigment. From here, the answer was a little clearer: since there was some sort of explanation for every pigment featured, and since we know a pigment called “brazilwood” was popular during this time-period (which wouldn’t have shown up on the spectra because of the organic components being too sensitive), we came to the conclusion that the red pigment in this initial came from brazilwood, or madder. By the process of elimination, this case was closed.

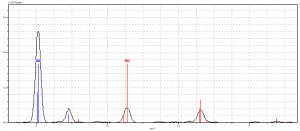

Our Second Site: Red Rubrication

This was our easiest site throughout the process. In our first analysis, we found copper, calcium, mercury, and iron in the spectra readings. Once again, because the parchment contains calcium and iron, we were able to determine the main source of pigment being from mercury (striking out copper since it was in all of our findings). Mercury was used to make the popular pigment vermillion (or cinnabar), so this was a clear-cut answer.

Our Third Site: Dark Red Berry

One of the mysteries of our manuscript fragment was the dark red berry we found on the column beside our text. There were bright red berries nearby, so what was going on with this one? Was it just a stain, or was it actually a different pigment entirely? To answer these questions, we took our first reading of the site. The pXRF showed calcium and iron from the parchment, with copper and lead as potential elements that would affect the pigment. This left us grasping for explanations. Maybe it was the azurite/red lead mixture from before? Then we realized: there’s a green leaf right next to the berry! This would explain the high amounts of copper and lead, since those were very prominent in any green pigment at the time.

From here, the only suitable explanation was one we had used before: because organic pigments are so low on the atomic scale, they were probably buried beneath the louder elements. Like our first site, we found it safe to say that this berry was probably colored with madder and brazilwood, due to its high popularity at the time and availability in the French region of this manuscript.

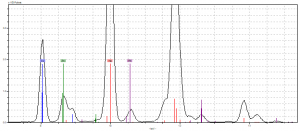

Our Fourth Site: Bright Red Berry

In our fourth site, the bright red berry near the darker one, we anticipated finding a similar chemical makeup, but one particular aspect of this site intrigued us. As seen above, there was a noticeable spill of a mystery substance near one of the red berries. In our pXRF reading, we found the parchment elements (calcium and iron, again) along with the pigment elements mercury, lead, copper and zinc. Originally, we assumed that it might be contamination from the spill, but then we realized: there are green leaves right next to this spot as well! This deduction left us with lead and mercury as the main elements.

To be sure, we took our second reading of the materials and this time decided to try two bright red berries: one near the mystery spill and another that was a safe distance from the leaves. The berry near the leaves once again showed the previous elements. The other berry, however, was pure mercury! The clarity of this non-contaminated berry led us to strongly believe that these berries were made from similar vermillion pigments– there is no other pigment with such strong traces of mercury.

So What Does All That Science Stuff Mean?

Well, first of all we can look back to our original questions about what these pigments suggest. There was a consistent preference of vermillion over red lead in this fragment, and knowing that vermillion is significantly more expensive, we can assume that the buyer of this Book of Hours is wealthy. We also know that there was a trade system between France and Turkey during the 1400s. There was a port in Turkey, Sinope, popularly known to trade vermillion, so we can even go as far as to trace the pigment back to there. As for the brazilwood, France would have been trading with the brazilwood port Ceylon (modern-day Sri Lanka) through a trading route in Egypt.

In retrospect, it’s hard to look back on this and not see how cool it is! Just from this collision of interdisciplinary study, we’re able to trace a manuscript back to France and pigments to small ports in Turkey and Sri Lanka! There aren’t many classes that get to cover such a broad and deep range. We could only find these answers by appealing to history, geography, chemistry, and the process of elimination— an exhausting but hugely satisfying experience.

All in all, that’s what this project and class has taught us: the necessity of being a student of all disciplines. Through this process we became scientists, historians, organizers, and better English students. This one page out of an old book took us through time and space to land us on the other side with its story. There’s a wide range of knowledge to carry with us from this kind of learning process, and if nothing else it will definitely keep us thinking about medieval literature in fresh ways from here on.

Sources:

Benhamou, Reed. “Verdigris and the Entrepreneuse.” Technology and Culture, vol. 25, no. 2, 1984, pp. 171–181. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3104711.

“Hours of the Cross & Hours of the Holy Spirit.” Books of Hours, Les Enlumineres, Web. 3 December 2017.

Howard, Helen. Pigments of English Medieval Wall Painting. London: Archetype, 2003. Print. Hunt, Alice M. W. and Robert J. Speakman. Doing pXRF Right: An intermediate course for

Archaeologists. Center for Applied Isotope Studies at the University of Georgia, 2015.

“Leaded Brasses.” Copper Development Association, Inc. Web. 4 December 2017.

Marieflemay [Marie-France Lemay]. “Verdigris.” Traveling Scriptorium. Yale University Library, 17 Jan. 2013, https://travelingscriptorium.library.yale.edu/2013/01/17/verdigris. 4 December 2017.

Melo, Maria João, Vanessa Otero, Tatiana Vitorino, Rita Araújo, Vânia S.F. Muralha, Ana Lemos, and Marcello Picollo. “A Spectroscopic Study of Brazilwood Paints in Medieval Books of Hours.” Applied Spectroscopy, vol. 68, no. 4, 2014, pp. 434-444.

Panayotova, Stella, Deirdre Elizabeth Jackson, and Paolo Ricciardi, eds. Colour: The Art and Science of Illuminated Manuscripts. London: Harvey Miller Publishers, 2016. Print.

Thompson, Daniel V. The Materials and Techniques of Medieval Painting. New York: Dover Publications, 1956. Print.

Trentelman, K., C. Schmidt Patterson, and N. Turner. “XRF analysis of manuscript illuminations.” Handheld XRF for Art and Archaeology. Ed. Aaron N. Schugar and Jennifer L. Mass. Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2012.