If you’re like most people, you probably would not expect to walk into a college English class and hear the students throwing around phrases like “lead’s escape peak” and “the spectrometer’s sample size” while examining a periodic table as they manipulate some strange-looking graphical data on their laptops. And yet that is exactly what we in Dr. Camp’s Literature in the Library class have done for the last few weeks of this semester!

To round out our class’s study of medieval manuscripts, we have spent several weeks studying select manuscript fragments from UGA’s Special Collections Library using a chemical analysis tool called a portable XRF machine (pXRF) – see this post and this post to learn more about how it works!

Our goal in using this technology was to see if we could figure out the precise identities of the pigments used on these fragments. Discovering such information about a manuscript is valuable for a number of reasons, both from a historical standpoint (learning what pigments were most commonly used in different times and places and what that tells us about trade routes, production techniques, etc.) and from a practical one, since we are much better able to determine how to care for and preserve such fragments once we know what they are made of.

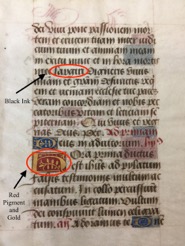

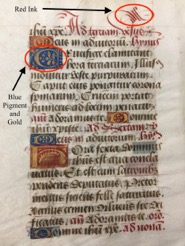

One of the fragments that we investigated over the course of this unit is a 9.3” x 4.3” leaf from a French Book of Hours – a common devotional book of the time – which dates from sometime in the later fifteenth century.

As you can see in the pictures above, both its verso and recto sides consist of a single column of black text with red rubrication, red and blue decorated initials, and gold embellishments on the initials. Since our goal was to figure out the identities of the pigments used in our fragment, we decided to use the pXRF machine to sample four different spots: a spot of red rubrication at the top of the verso, an area of black ink from the recto, and one of each of the red and blue initials. You can look at the pictures to see exactly where we sampled!

After taking our samples and examining the resulting spectra, we found that the black ink and blue pigments were pretty straightforward and matched our expectations well, so we felt confident identifying them as iron-gall ink and azurite. The two red samples on the other hand, though we still feel comfortable in our identification, gave us more trouble than the other samples. Thus, we will talk about the reds in more detail.

Hypothesis

Because we had done some research at the very beginning of this unit on how different colors of the medieval palette were most commonly produced, we had something to go on as we started forming ideas about this particular fragment.

By just looking at the two red spots closely, we came to the belief that the red ink and red initial pigments were probably the same. We wanted to sample both, however, in order to confirm this. We thought that it was most likely that both would be the pigment vermillion because it is the right scarlet-red color and because it was in popular use in Europe at this time. We therefore knew to watch for the presence of mercury (Mg), since vermillion is mercury sulfide (MgS). We also expected gold (Au), of course, in the red initial’s spectra because of the decorations.

Results

After taking readings of our four initial sample areas, as well as a later addition of a spot of blank parchment as a “control” of sorts to filter out elements present in the parchment itself, we found that all three of our guesses as to pigment identities appeared to be correct! Only the results for the red samples gave us major trouble, which is why we are going to switch gears now to only talk about this particular color’s results.

The Copper Problem

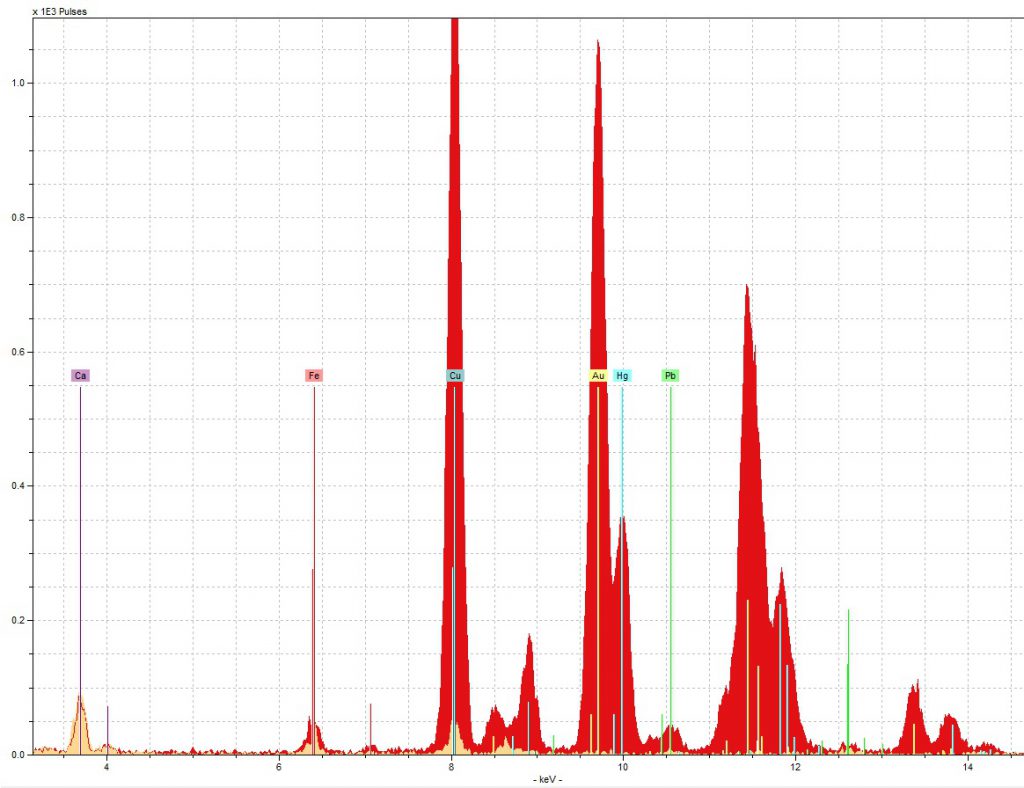

The first and most noticeable issue we ran into was the perplexingly high concentration of copper in the red initial sample.

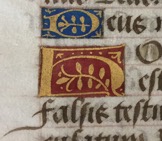

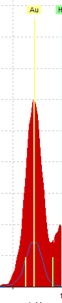

As you can see in the spectra below, though we did find the mercury we expected for vermilion, there was also slightly more copper in the red initial than there was gold, and that is despite all the gold you can see in the picture of the sample area to the right!

To try and figure out what might be happening here, we overlaid the red initial and blue initial’s spectra, and found something interesting:

As you can see to the left, there was about four times as much gold in the red initial’s spectra as there was in the blue initial’s, which surprised us given that both are decorated in the same manner and thus, it seemed to us, should have approximately the same amount of gold. Since the high volume of gold was thus another strange thing about the red initial, we wondered if the gold and copper issues might be related.

Further research into gold revealed that it may have been that the particular gold used here was an alloy with copper (“Gold leaf”, Encyclopedia Britannica), and the reddish tint of the gold supports the idea that if so, the ratio of gold to copper was relatively high (Emsley). Though we cannot say for sure that the ratio was 50:50, in other words, it is a possibility, and it seems to be the best explanation that we can propose at the moment without further investigation.

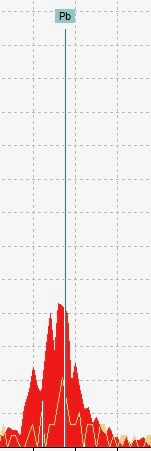

The Lead Problem

The second problem we faced was the unusually large amount of lead in the red ink. We had originally expected for lead to show up in all of our spots because scribes ruled parchment with plummet, a piece of lead alloy (“Ruling”, Medieval Manuscript Manual). However, the issue with this was that there was simply too much lead to be accounted as ruling.

We cannot explain why there was such a high amount of lead in the red ink. It is peculiar because there is no ruling lines near the spot and there is nothing but blank parchment behind this page.

This insinuates that there is something else that accounts for this lead. Some possible options we came up with were white lead and red lead. White lead, a carbonate of lead, was often mixed with other paints by medieval artists to create a lighter tone (“White Lead”, Pigments Through the Ages). However, white lead tends to turn black when mixed with sulfide paints such as vermillion, the red pigment of our fragment (Sabin 46). Similarly, red lead, which is a lead oxide, is also incompatible with sulfide paints (Feller 114). Therefore, we do not know where the lead is coming from.

So What’s Next?

Because we could not figure out with why there was such an excess amount of copper and lead in some of our spots, it would be wonderful if additional research was conducted. We would recommend for future researchers to utilize near-infrared imaging, which is a device that detects any underdrawings (“Near-infrared imaging”, Fitzwilliam). We were thinking that maybe some paint was spilled onto the parchment, which might be a reason for the copper and lead.

Overall, this project has been a really unique and rewarding experience. After all, our class was the first group to ever scientifically analyze the Hargrett Library’s medieval manuscripts! It was fun working with such a diverse group of people who came from fields such as English, Latin, Theater, Computer Science, Arabic, and International Affairs. Because of this class, we have all, despite our different backgrounds, transformed into devoted scientists and faithful protectors of manuscripts.

-Bonnie Hester and Michelle Chang

Sources

Emsley, John. Nature’s Building Blocks: An A-Z Guide to the Elements. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Feller, Robert L., et al. Artists’ Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics. Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1986. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/008232136

“Gold Leaf.” Encyclopædia Britannica, September 2014. Web. 22 October 2017. https://www.britannica.com/art/gold-leaf.

“Illuminated.” The Fitzwilliam Museum. University of Cambridge Museums, n.d. Accessed 17 Oct 2017. www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/illuminated/lab/lab.

Lemeneva, Elena. “Ruling.” Medieval Manuscript Manual. Budapest: Central European University. Web. 4 Dec. 2017. http://web.ceu.hu/medstud/manual/MMM/ruling.html

Sabin, Alvah Horton. White-Lead: Its Use in Paint. London: Chapman & Hall, 1920. Google Books. Web. 4 Dec. 2017. https://books.google.com/books id=HWxZAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_%20summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

“White Lead.” Pigments Through the Ages. WebExhibits. Web. 6 Dec 2017. http://www.webexhibits.org/pigments/indiv/overview/leadwhite.html