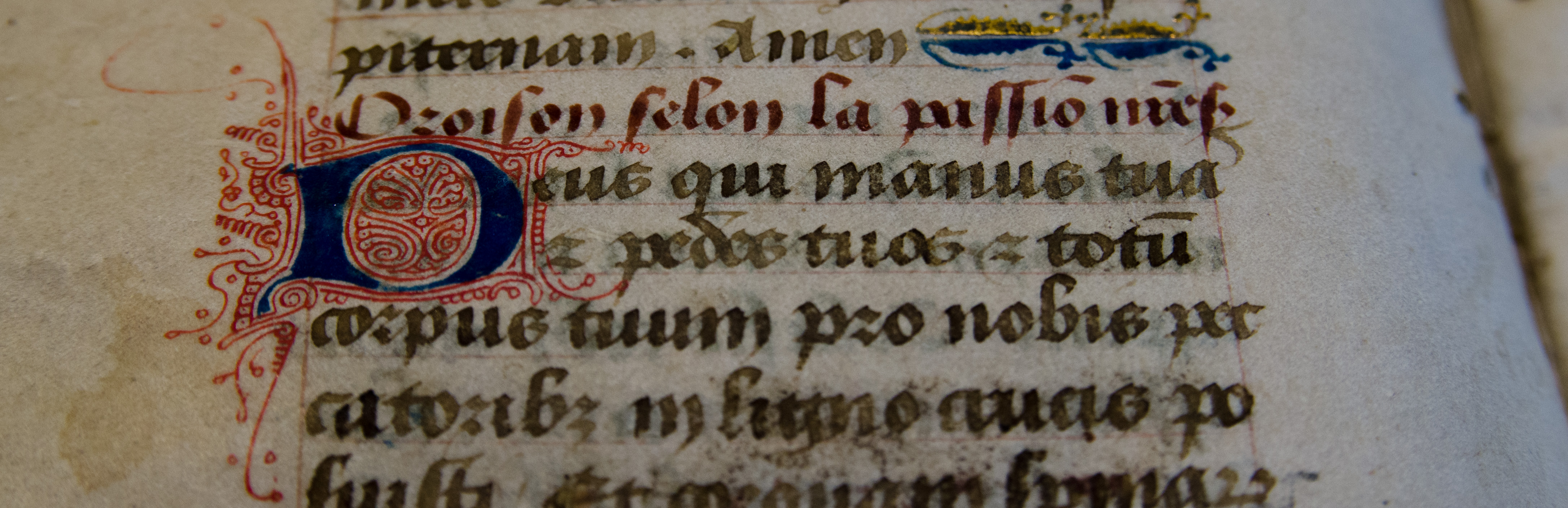

The Fall 2018 iteration of the Hargrett Hours Project has been working all semester towards a digitized edition of our lovely Book of Hours. Lo and behold, it’s here! This website is the product of two months’ worth of work divided into (roughly) three parts: Team Website, Team Gospels, and Team Prayer, respectively working to create the website and interpretive essays for the Gospels and Prayers.

During the process of our research, passion devotion became one of our buzzwords. Each of the prayers refers to the Passion in a definitive way, as can be further seen in the prayer-by-prayer analysis found in our interpretative essay. In the essay, we contextualize the devotional sequence as a spiritual product of the Passion relics housed in Sainte-Chapelle of Paris: the Crown of Thorns, a fragment of the True Cross, and a vial of Christ’s blood (Bottineau).

With the prayers of the Hargrett Hours so distinctively positioned to encompass Passion devotion, our team speculated on the form that the Hargrett Hours’ user’s devotion would have taken.Where does the Hargrett Hours fit in to the larger scheme of Passion Devotion? Our initial hypothesis was that the users of the Hargrett Hours used the prayers for personal (read, private) devotion outside of the Church. This understanding of the prayers’ intended use would match the typical use of Passion prayers; as a highly personal devotional mode, the affective devotion encouraged by the Passion would likely be confined to a more private setting. However, this is not strictly the case. During the course of our research, we found that the prayers within the Hargrett Hours could be grouped into three sections based on focus and use:

Prayers 1-3 (Latin): Passion prayers centered on the Crown of Thorns

Prayer 4 (Middle French): Passion prayer with a rubric that indicates it should be read during mass

Prayers 5-7 (Latin): Elevation prayers popular as accessory texts

All seven prayers focus on Passion devotion, but a shift occurs at Prayer 4. The rubrics preceding Prayer 4 instruct the reader to read this prayer between the Pater Noster and the Agnus Dei during the mass. Not only does Prayer 4 divide the two Latinate prayer groups, but it creates a section of prayers associated with the mass, comprising Prayers 4 through 7. This change marks a distinct shift from private to public devotional practice inherent in these prayers that our team did not anticipate.

The practice of reading prayers during mass was common; owners of Books of Hours could bring their manuscripts, often containing some works in the vernacular as in Hargrett’s Middle French prayer, as a supplement during mass (Reinburg 192). As this practice grew in popularity, Books of Hours that were intended for use during mass would contain at least one prayer “designed to be said at the elevation of the host, probably the most visually recognizable moment of the rite” (192). The Hargrett Hours contains three such prayers, “Anima Christi sanctifica” (Prayer 5), “Domine ihesu xpiste…” (Prayer 6), and “Ave Domine Ihesu Xpiste Verbum Patris…”(Prayer 7), all of which follow after Prayer 4 to create a devotional set of tied to the elevation. Prayer 6 (“Domine”) is the elevation prayer most commonly found in Books of Hours, a popularity likely linked to other iterations of the prayer’s rubric (Reinburg 192). The rubric often cites both Pope Boniface and Philippe IV, lending “both royal and papal authority to the prayer, and the length of the indulgence attached to this prayer is two thousand years (193).Prayer 6 (“Domine”) also links the Hargrett Hours back to Sainte-Chapelle; Pope Boniface VIII and Philippe IV were engaged in a dispute at the turn of the fourteenth century that was partially diffused by Boniface’s canonization of Louis IX, Philippe’s grandfather and the king who ordered the construction of the Sainte-Chapelle (Gaposchkin). Not only does the rubric contextualize this prayer’s place within a devotional practice, it also further connects the prayer to the history of the chapel from which it derives its devotional focus and in which it was likely read.

Examining the setting of the usage of these prayers is therefore a fascinating entry point. It was common for medieval church-goers to read prayers during mass, explaining the presence of vernacular works and vernacular rubrics. These prayers, like the Hargrett Hours’ Middle French Prayer (4), served as a supplement during mass (Reinburg 192).

The practice of reading individual prayers during mass grew in popularity amongst church-goers; soon, a Book of Hours would contain at least one prayer included to be said upon the elevation of the host during mass (Reinburg 192). In line with this tradition, the Hargrett Hours contains three Elevation prayers: “Anima Christi sanctifica” (Prayer 5), “Domine ihesu xpiste…” (Prayer 6), and “Ave Domine Ihesu Xpiste Verbum Patris…”(Prayer 7). These three prayers together create a devotional set of prayers tied to the elevation, joined with the first three prayers through the Middle French prayer, which was to be read during the prayers immediately after the elevation.

The grouping of the Hargrett Hours’ fits within standard structure of a Medieval Mass. During the Elevation of the Host “the celebrant usually said this prayer in a low voice, with his back to the people, and in order to inform the congregation when the consecration had taken place, it became usual from the twelfth century [onward] for the priest to hold the consecrated host above his head for all to see, and for a handbell to be rung three times by a server… [and] while the whole congregation waited on God in silence,” the Pater Noster and Agnus Dei would be sung (Hamilton, 58). Prayers 5, 6, and 7 likely would have been read privately during the quiet prayer sung by the celebrant, his back turned to the congregation during the Elevation of the Host (here’s a visual of how this would look, for all of us non-Catholics).

The elevation is a strictly visual cue for the members of the congregation, a way to notify them that transubstantiation has taken place and they are now seeing Christ’s body and blood. This adds an interesting dimension to our elevation prayers. The prayers in the Hargrett Hours are not accompanied by miniatures of the Passion, but reading Passion prayers during the elevation could provide a similar sort of visual aid to Hargrett’s first user. They would be seeing Christ’s Passion through the Eucharist, living relics of the Passion raised above the congregation in silence.

This, of course, is conjecture. We don’t know enough about who Hargrett’s first owner was, or where they would have prayed, or how they would have read this manuscript to say anything concrete about the purpose of this distinct group of prayers. However, what little we are able to say about the construction and intention behind this sequence of prayers serves to add more depth to Hargrett’s unique devotional practice.

References

Gaposchkin, M. Cecilia. The Making of Saint Louis: Kingship, Sanctity, and Crusade in the Later Middle Ages. Cornell University Press, 2008

Hamilton, Bernard. Religion in the Medieval West. Hodder Arnold, 2003

Reinburg, Virginia. French Books of Hours: Making an Archive of Prayer, 1400-1600. Cambridge University Press, 2012