We love medieval manuscripts, and can’t help but be interested in the lives of the people who created them. I mean, that’s the point of studying them, isn’t it? We are trying to figure out what stories these manuscripts can tell us about the Middle Ages and the people who lived then. These books and fragments are some of our best connections to their lives. As women are often the first to be overlooked in history, I was especially interested to find out what roles they played in making these manuscripts.

To start off, I wanted to explore women’s roles in the Middle Ages in general. According to an article published by the British Library, these roles were many and diverse. A peasant woman would have many domestic responsibilities, help her father or husband with agricultural labor or his craftsmanship, and also be responsible for cottage industries such as beer- and fabric-making. An aristocratic woman would give these chores to her servants, and usually spend her time hunting, playing games, and engaged in religious activities (here is a link to a blog post from a previous semester which analyzes women and medieval prayers and this is a link to another blog post about women as readers of primary religious works). As far as a woman’s social standing, they were considered innately inferior to men, and therefore had very little control over their lives. Most women made the choice between marriage and becoming nuns. Women had access to power through the church as abbesses or to political power as queens or regents. Otherwise, a woman in the Middle Ages had relatively limited access to power, and limited authority over their own lives.[1]

Because medieval women had such limited options, the women I discovered are really exciting figures to consider. Despite their social standing, these women are exceptional examples of what women, and all oppressed groups, have been doing since the beginning of time – overcoming the social pressures and expectations holding them back.

One of these spectacular women, Christine de Pizan, is my favorite of them all. Born in 1364 to an aristocratic family, Pizan had the unique opportunity to learn to read and write, which was quite uncommon for women of this time. Though she was happily married, both her father and husband died before she was twenty-five years old, leaving Pizan alone to support her mother and children. Though this is a heartbreaking story, this is exactly the point where it gets the most exciting. To support herself and her family, Christine de Pizan, a woman in the Middle Ages, became the first professional writer… ever. [2]

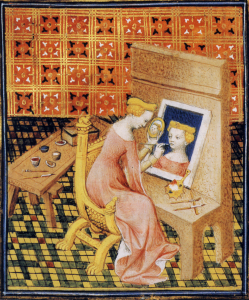

It is in her writings that we find mention of some other fascinating medieval women with influence on manuscript production in this time period. In her famous work The Book of the City of Ladies, Pizan mentions a famous and skilled female illuminator, Anastasia. This woman, she writes, “is so good at painting… for miniatures that there is no craftsman who can match her in the whole of Paris…” [3] Another famous illuminator, Marcia, is mentioned both in City of Ladies and in Giovanni Boccaccio’s Famous Women [4]. According to Boccaccio, Marcia, heralded for her virginity, could “paint with such skill and finesse that she surpassed… the most famous painters of her day.” These women – Christine, Anastasia, and Marcia – used their skills and their ingenuity to defy social customs and make their own paths, which lead to the creation of many of the beautiful medieval works we see today.

Though my research introduced me to so many amazing medieval women who I would have loved to include in this post, I felt it would be incomplete without mentioning women’s roles on a much larger scale. Neither Christine or either of the famous illuminators could’ve done their work without pigments to create their paints, and the medieval period saw the transition to a large-scale production of one pigment, verdigris, which was eventually dominated completely by women. Verdigris is an inorganic pigment, primarily consisting of copper, which was used to create a vibrant blue-green[5]. When you look at a really old painting in a manuscript, and you see areas where the parchment is almost completely corroded away, there’s a chance you might be seeing the handy work of this popular pigment. One article I found in my research described the process of verdigris production in the 18th century. By this point in the pre-modern era, verdigris production was so thoroughly dominated by women that there was even a social stigma to it![6] While this complete industry control did not occur until after the middle ages, it is clear from Benhamou’s article that there is evidence of this transition occurring in the middle ages. What’s really cool about his article is that he lists real women who actually lived in the 1400s by name alongside their husbands in record books. This is the concrete evidence of women slowly, but inevitably, becoming involved in verdigris production.

So, what does this tell us? To me, the inclusion of women in each of these aspects of manuscript productions shows that these manuscripts provided women with new opportunities, and that they used these opportunities well. Because of Pizan, women can forever claim the position of the first professional author. Thanks to Anastasia, Marcia, and countless other female artists and illuminators (and the pigment makers breaking into the industry and beginning the tradition of female verdigris production), women’s touches are (hopefully) forever preserved in these amazing medieval works, which are today the subject of so much study, interest, and discovery.

[1] Bovey, Alixe. “Women in medieval society.” The Middle Ages, The British Library, 17 Jan. 2014, www.bl.uk/the-middle-ages/articles/women-in-medieval-society.

[2] Morrison, Susan Signe. A Medieval Woman’s Companion : Women’s Lives in the European Middle Ages. Oxbow Books, 2016. EBSCOhost, proxy-remote.galib.uga.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=1243061&site=eds-live.

[3] Pizan, Christine De. The Book of the City of Ladies. Translated by Rosalind Brown-Grant, Penguin Classics, 1999.

[4] Boccaccio, Giovanni. “Marcia, Daughter of Varro.” Famous Women, edited by James Hankins. translated by Virginia Brown, Harvard University Press, 2003, pp. 135–137.

[5] “Verdigris.” Pigments through the Ages, www.webexhibits.org/pigments/indiv/technical/verdigris.html

[6] Reed Benhamou, author. “The Verdigris Industry in Eighteenth-Century Languedoc: Women’s Work, Women’s Art.” French Historical Studies, no. 3, 1990, p. 560. EBSCOhost, doi:10.2307/286487.