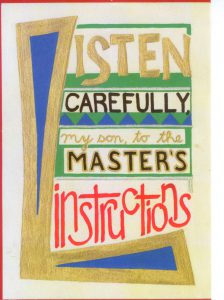

One of my all-time favorite assignments in these manuscript classes is the Make Your Own Manuscript project. It’s configured differently for different courses, but the main idea stays the same: the students use everyday office supplies to make their own quires: folded, stitched, handwritten, hand decorated. They have carte blanche as to contents — it doesn’t have to be “medieval-y,” and the text can be literally anything. I’ve gotten German, French, Chinese language manuscripts; manga illuminations; glitter and ribbon binding; flame-and-oven ageing; crocheted covers. Every year, first-years or seniors, my students blow me away in this assignment.

Why do I love it so much? Not just because I get Harry Potter in Latin and Korean fairy tales. Rather, because it gives the students a small taste of the labor that went into making a medieval manuscript. We can talk in class about scraping the hides with a lunellum, about pricking and ruling, about how many lines of text a scribe could produce in a day. But that’s all academic. It’s something else to be the rule-er, or scribe, or illuminator yourself. It’s something else to fret over your own errors (and to make your peace with them), or to look with satisfaction on a well-executed carpet page. Students walk away with a deeper appreciation for the effort that went into each page of a medieval manuscript, and a greater-than-passing appreciation for the “amusing” complaints that scribes left in the margins of manuscripts.

The assignment actually picks up a gauntlet that Thomas Hoccleve threw down:

Many men, fadir, weenen that wrytynge

No travaille is; they holde it but a game;

Aart hath no fo but swich folk unkonnynge.

But whoso list desporte him in that same,

Let him continue and he shal fynde it grame;

It is wel gretter labour than it seemeth;

The blynde man of colours al wrong deemeth.[Many men, father, believe that writing isn’t any work; they think it’s just a game. Art has no enemy except those people who are ignorant. But whoever wants to amuse himself in that same way, let him get on with it and he’ll find it a vexatious activity. It’s a much greater labor than it seems; the blind man judges colors all wrong.]

(Regiment of Princes, lines 988-94)

Vexatious? Absolutely! It’s incredibly tedious to write everything by hand, especially if you’re copying someone else’s text. That tedium is something that Melville captured well in “Bartleby the Scrivener,” where Bartleby goes about his work “silently, palely, mechanically” (para. 18) — and ultimately, not at all. Students do find this to be true: ruling a page is boring and interminable, even when you’re re-watching Buffy while doing it. Again, Hoccleve:

But we laboure in travaillous stilnesse;

We stowpe and stare upon the sheepes skyn,

And keepe moot our song and wordes yn.[But we (scribes) work in laborious silence: we stoop and stare at the sheepskin, and must keep our own song and words within.]

(Regiment of Princes, lines 1013-15)

Hoccleve identifies two further downsides to writing a manuscript: it’s solitary, and it stifles the creative spirit. Hoccleve is probably exaggerating for the sake of effect, but it is true that the work of the scribe was not inspiring (as again “Bartleby the Scrivener” witnesses).

I do want the students to experience a bit of that solo drudgery — Hoccleve is right that you only really understand a manual task or fine craft in all its frustrations if you try it yourself. Generally, however, I have designed this assignment (especially as I am running it in this class) to prevent too much tedium. First, by giving the students full creative license, they aren’t obliged to “keepe … [their] song and wordes yn.” Second, this semester the assignment is collaborative: groups of three students must work together to produce their quire, and our pair of graduate students will bind the class quires into a book. This division of labor reflects microcosmically the many hands and minds that went into the creation of medieval manuscripts. And hopefully it’ll build class camaraderie in the process.

Of course, what the students do is a far cry from the true manual labor (and stink, and mess) of actual manuscript production. While I would love to run this assignment beginning with an untreated hide (rephrase: I’d love to have the skills to begin with a hide), I also fear that the learning curve of cutting a quill or forming letters with iron gall ink would detract from the purpose of the assignment: to create. To have both the frustrations and the joy that come with carefully executed handiwork.