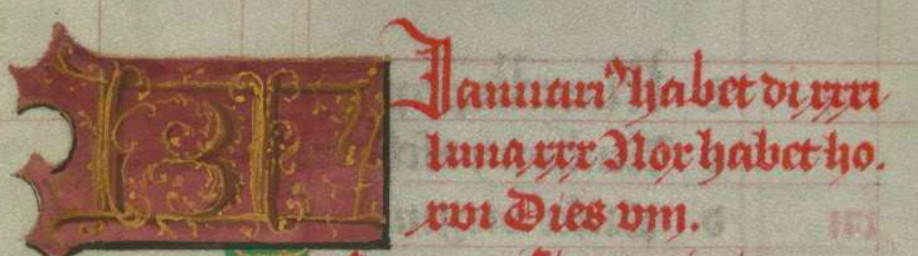

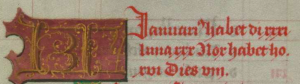

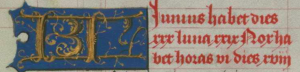

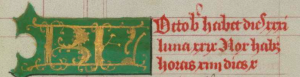

For our research project in Unit 2, I studied the the Aussem Hours, W.437 at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, MD, made for the Aussem family in Cologne, Germany (Köln) in the early sixteenth century. I was particularly interested in the calendar pages found on 6r – 17v. Typical calendars in medieval books of hours include a short description of each month, which includes the name, and the length of the actual and lunar month. On each page of the calendar for the Aussem Hours, this information also includes the number of hours found during the night. Clemens and Graham briefly discuss these types of calendars, noting “some calendars tell one “how many hours of light and darkness days have”1. Of course, we know now that the exact length of night changes daily, but without our modern equipment (or perhaps, modern interest), detecting slight variations would have been difficult. The duration of night in the Aussem Hours, overall, is surprisingly accurate. The first figure comes from the calendar page for January. Starting midway through the second line, it reads “Night has 16 hours, day 8 / Nox habet hor(as) xvi, dies viii.” According to TimeandDate.com, the days in Cologne are 8 hours long in January, so the nights are 16 hours long. The same holds true for my other two figures. In June, the calendar reads “Night has 6 hours, day 18 / Nox habet horas vi, dies xviii,” and TimeandDate agrees. October, with 14 hours at night and 10 in the day (Nox hab(et) horas xiii, dies x) according to the calendar, is one hour off at the beginning of the month, but there are 10 hours in the day by the 26th.

For our research project in Unit 2, I studied the the Aussem Hours, W.437 at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, MD, made for the Aussem family in Cologne, Germany (Köln) in the early sixteenth century. I was particularly interested in the calendar pages found on 6r – 17v. Typical calendars in medieval books of hours include a short description of each month, which includes the name, and the length of the actual and lunar month. On each page of the calendar for the Aussem Hours, this information also includes the number of hours found during the night. Clemens and Graham briefly discuss these types of calendars, noting “some calendars tell one “how many hours of light and darkness days have”1. Of course, we know now that the exact length of night changes daily, but without our modern equipment (or perhaps, modern interest), detecting slight variations would have been difficult. The duration of night in the Aussem Hours, overall, is surprisingly accurate. The first figure comes from the calendar page for January. Starting midway through the second line, it reads “Night has 16 hours, day 8 / Nox habet hor(as) xvi, dies viii.” According to TimeandDate.com, the days in Cologne are 8 hours long in January, so the nights are 16 hours long. The same holds true for my other two figures. In June, the calendar reads “Night has 6 hours, day 18 / Nox habet horas vi, dies xviii,” and TimeandDate agrees. October, with 14 hours at night and 10 in the day (Nox hab(et) horas xiii, dies x) according to the calendar, is one hour off at the beginning of the month, but there are 10 hours in the day by the 26th.

When I first encountered these descriptions, I was thinking, what are these “hours”? How long are they? Are they anywhere close to our hours? The only conception of hours in the medieval period I had was monastic hours, a type of unequal hours. These hours were regulated, at least within individual monastic communities, and the day and night were divided neatly into groups of hours. The liturgical hours that fell during daylight, which Harper identifies as Prime, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers, and Compline 2, were probably not regular intervals from day to day, but instead the number of daylight hours were divided by six. So in a month like January, with only 8 hours, each hour would be about 1 1/3 of our hours long. In a month like June, however, each monastic hour would be three hours long. Knowing this information, I was surprised to find 24 hours in a day in the Aussem calendar. Glennie and Thrift’s book suggests that “conceptions of time need to be historically constituted,” and they warn against using modern temporal conceptions to think about medieval time 3. I started out doing what they suggest, and now I’m in the middle somewhere. I know our hours are not exactly the same, probably, but I’m not sure what exactly their hours were. It seems the main difference between our time keeping and theirs is that when we keep time we are very exact and by the minute, while the variance in the nightly hours in October suggest they didn’t feel the need for that level of exactness.

Had I known more about the history of time keeping in Cologne, this addition of nightly hours would not have surprised me. Dohrn-van Rossum believes there was a public clock in Cologne before 13724, and the clock tower in the city hall, Kölner Rathaus, was built around 1407. Though Dohrn-van Rossum debunks the idea that there was a full street of clock makers in Cologne in the middle ages, he does suggest that “modern hour-reckoning started in Cologne in 1374,” and presents numerous examples. Though there was not a guild of clock makers or even a full street of them within the city, keeping time was very important well before the Aussem Hours was compiled. Though the Walter’s description states the Aussem Hours was made in Germany, that doesn’t mean it was made in Cologne, however; books of hours produced for patrons were not always made in the same city in which the patron lived. It will take further research to determine if including hours in the night was a German practice, a 16th century practice, or maybe totally random. My instinct is to equate the city’s timekeeping practices with the book itself, but manufacturing books of hours was not that simple of a process. No matter where it was made or why the nightly hours are included, the Aussem Hours calendar is a good example of how we cannot reduce medieval practices as lesser versions of ours, but rather as something parallel but different.

–JH Roberts is a contributor to Mimisbrunnr.info, a blog for developments in ancient and medieval Germanic studies, and a PhD student at the University of Georgia.

Note on images:

All images come from the Aussem Hours, W.437, held at the Walters Art Museum. The January calendar is found on folio 6r, June on f. 11r, and October on 15r. The digital manuscript is held under Creative Commons License CC0.

Notes

1. Clemens, Raymond, and Timothy Graham. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithaca, NY: Cornell U P, 2007. Print. p. 196.

2. Harper, John. The Forms and Orders of Western Liturgy from the Tenth to the Eighteenth Century: A Historical Introduction and Guide for Students and Musicians. New York: Oxford U P, 1991. Print. p. 45.

3. Glennie, Paul., and N. J Thrift. Shaping the Day: A History of Timekeeping in England and Wales 1300-1800. New York: Oxford U P, 2009. Web. 14th October 2016. p. 12.

4. Dohrn-van Rossum, Gerhard. History of the Hour: Clocks and Modern Temporal Orders. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996. Print. pp. 96 and 234, respectively.