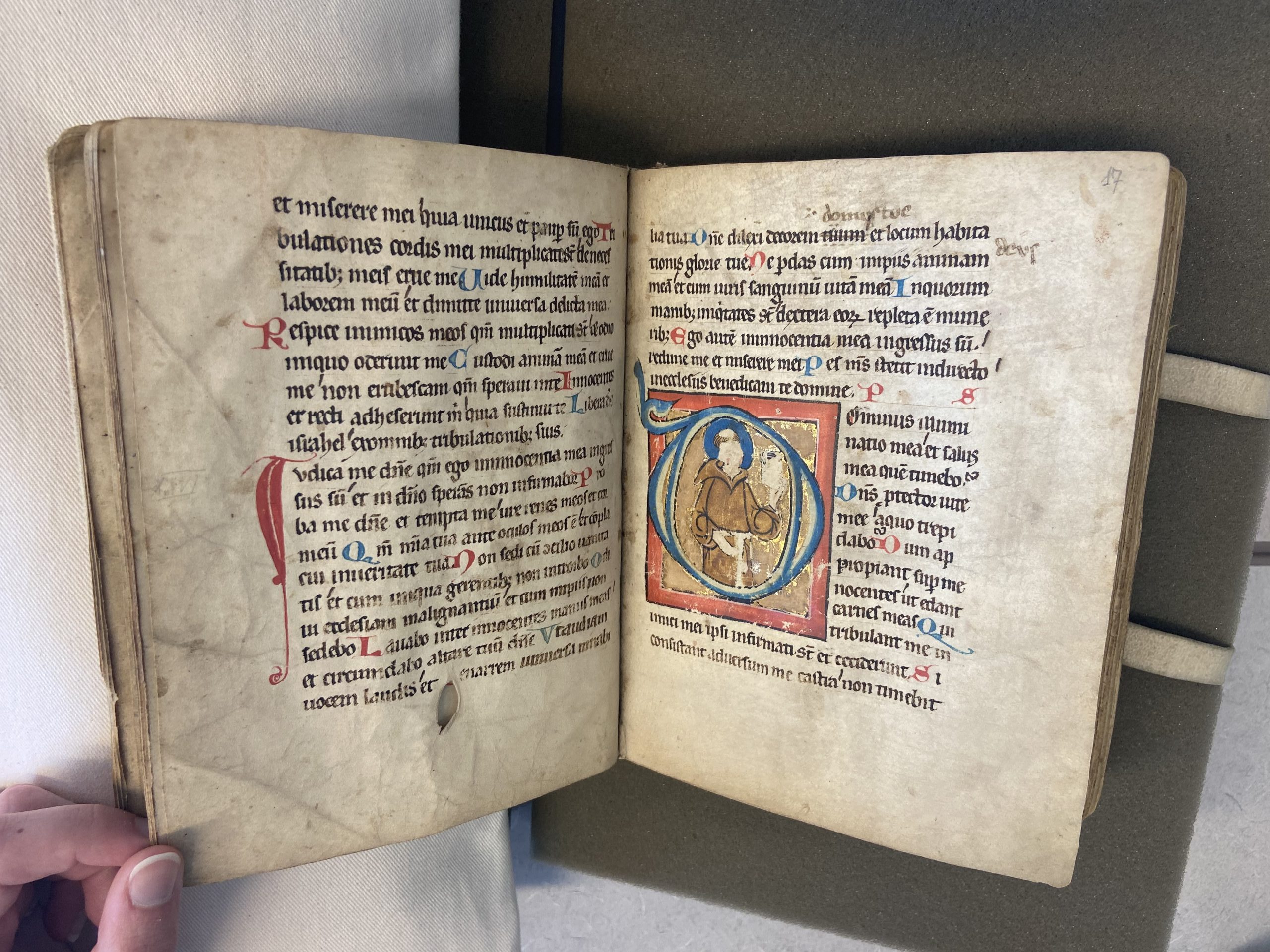

From the beginning of my journey in medieval literature with Dr. Camp, I’ve been intrigued by the uniquity of manuscripts. One of the most impactful lessons I learned from class this semester is that no two manuscripts are alike. While looking at the Constance Psalter, I was intrigued by the scratching out of St. Francis and St. Dominic’s faces (f. 17r and 73r). The way people interacted with their own books reminded me so much of today’s active reading culture and added a new realm of uniqueness to the Psalter.

When I first looked at this Psalter, I was moved by the sheer deliberateness of the saints’ defacements— aka the scratching out of their images. The Psalter is parchment, a tough medium made from animal skin, meaning the owner who chose to deface these saints meant it. Furthermore, medieval manuscripts weren’t cheap. This Psalter would have been precious to its owner, and such aggressive changes suggest that the defacer wanted their edits to be evident to future readers. I wondered why? Why would someone deface these images—and only these? The owner of the Psalter deliberately chose to deface Saint Dominic and Saint Francis, just as they chose to leave Saint Michael alone. I was determined to find out why.

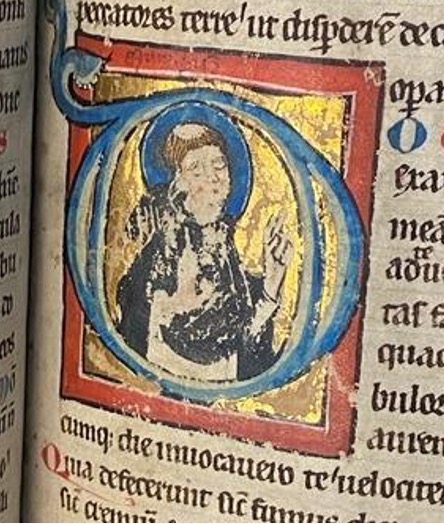

I wanted to be sure that the destruction of our Psalter wasn’t an isolated case, which led me on a wild goose chase for additional examples of defacement. The above example comes from a 15th century English Psalter; it displays an historiated initial introducing Psalm 109. God has been deliberately erased from the Psalter, like the scratches we see on our own Psalter. Defacement of saints was also not limited to our Psalter, which is evident in St John’s College MS. 208, an Office of the Dead featuring damage to Saint Thomas Becket.

The context of the defacement in our Psalter depends partially on when the manuscript was defaced. If we work with what we’ve got from the Les Enluminures’ description, we know the Psalter was produced sometime from 1240-1260 in Southern Germany in either the parish of Constance or Augsburg. There is also evidence that the Psalter remained in Germany into the fifteenth century, because we’ve got a note in German on folio 116 that’s dated 1467.

If the Psalter was defaced before 1517, it was likely a case of medieval antifraternalism, which I’ll discuss more shortly. However, if the Psalter was defaced after 1517, it was likely done during the Reformation under a sentiment against saints who weren’t in the Bible. The problem here is that there isn’t much information on the whereabouts of our Psalter, so we need to do some digging into our possible cases.

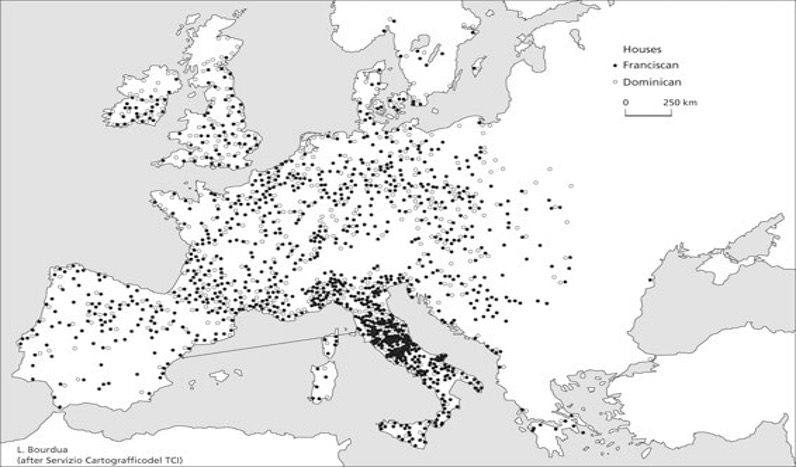

Let’s backtrack for a second. What in the world is medieval antifraternalism anyway? Medieval antifraternalism is opposition toward members of mendicant orders. I didn’t know what a mendicant order was, so I turned to Guy Geltner’s The Making of Medieval Antifraternalism for help. There, I found these orders were Christian religious groups that adopted a lifestyle of poverty and traveling for the purposes of preaching and ministering (Geltner). As the mendicant orders spread across Europe, many members encountered disdain and violence—cue, antifraternlism.

Ill feelings toward mendicant orders had roots in a variety of reasons, both circumstantial and ideological. Circumstantial opposition toward orders typically came from people in towns where the presence of orders threatened existing power hierarchy, laws, or resources. This made me wonder if St. Francis and St. Dominic had been scratched out by an antifraternalist owner.

I turned to tracking the orders via map, finally finding a map from Donald Logan’s A History of the Church in the Middle Ages, which details where the Dominican and Franciscan orders were in Europe during the 13th century. I then compared this map to one of Constance so I could determine relatively where Constance was on Logan’s map. There didn’t seem to be a large influx of Franciscan or Dominican orders in Constance—or surrounding areas in Germany, so I didn’t feel like there was much evidence to back up my antifraternalism theory.

Let’s turn back to our post- 1517 theory, which looks at the defacement in the context of the Reformation. Perhaps St. Francis and St. Dominic were defaced under an owner’s opposition toward saints who weren’t in the Bible. The type of defacement found in the Psalter led me to the popular Reformation practice of iconoclasm. Iconoclasm is the destruction of religious imagery. Such destruction ranged from individual acts to collective action, from mob attacks to vandalism. I found the portion about individual acts significant, especially since Maarbjerg describes such acts further as “individual acts of limited destruction of often very specific objects” (Maarbjerg 577). Exactly like the defacement in our Psalter. Now we’re headed in a good direction!

In his book Iconoclasm and Iconoclash, Willem van Asselt details the history of iconoclasm. Before the Reformation, iconoclasm was illegal and even seen as sacrilegious. Once city magistrates changed the law and began ordering the removal or destruction of certain images, iconoclasm became legal in Southern Germany (van Asselt 300). So, if our manuscript hung out in Germany before the Reformation, it’s likely that it wasn’t defaced until the Reformation since iconoclasm was previously illegal. I could therefore assume that if the defacement was done during the Reformation, it was done under a “down with worshipping saints” purpose.

At this point, I was still unsure why St. Michael was not defaced, especially when we consider the Reformers against worshipping all saints. With some help from Dr. Camp, I learned that different Reformers deemed different saints acceptable. It was likely that Saint Michael was not deemed an unacceptable saint because he is an archangel that appears in the Bible, so he’s typically seen as more scripturally legitimate. Many prominent medieval theologians, from St. Basil the Great in the fourth century to Alphonsus Salmeron in the sixteenth century, placed Saint Michael over the other angels– he earned the name archangel because he is the prince of the other angels (Holweck). Meanwhile, we’ve got Saint Francis and Dominic who were regular human guys, canonized and depicted in the Psalter merely a couple decades after their deaths. As such, their legitimacy could be downplayed by the Reformers.

As discussed earlier, these medieval manuscripts were super important to their owners. Families only owned a few books—if any—and these texts were often family heirlooms. The Psalter was often used for teaching children and for religious worship, especially during the Reformation. While a single owner could have defaced our saints, we cannot discount that a Protestant family may have done it as well, to “cleanse” the Psalter for their household.

At the root of all we know, we can be sure that the defacement of the Psalter fosters connection. People throughout history have been staunch in displaying their beliefs, whether in ways big or small. Psalters often taught children how to read Latin, and if it our Psalter was used as a teaching tool, it would have tied a family closer through the shared dislike of St. Francis and St. Dominic. Our Psalter is not only significant for its age, but for the touches humans left on it throughout history. Based on the evidence of iconoclasm, we can assume the Psalter was directly influenced by the Reformation– one moment in history captured forever.

Featured image: Defacement of Saint Francis in the Constance Psalter.

Works Consulted

“Detailed Record for Royal 2 B X.” Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts, The British Library, 25 Aug. 2005, https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/record.asp?MSID=6538&CollID=16&NStart=20210.

Drum, Walter. “Alphonsus Salmeron.” The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1912, https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/13402b.htm.

Les Enluminures, MS TM 789. https://www.textmanuscripts.com/medieval/medieval-german-psalter-79751

Holweck, Frederick. “St. Michael the Archangel.” The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1911, https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/10275b.htm.

Geltner, Guy. The Making of Medieval Antifraternalism: Polemic, Violence, Deviance, and Remembrance. Oxford University Press, 2012.

“Konstanz.” Map of Konstanz, Germany, https://www.freecountrymaps.com/map/towns/germany/1636999091/.

Maarbjerg, John P. “Iconoclasm in the Thurgau: Two Related Incidents in the Summer of 1524.” Sixteenth Century Journal, vol. 24, no. 3, 1993, p. 577., https://doi.org/10.2307/2542110.

“Mendicants: Greedy Beggars or Pious Missionaries?” Connected Mediterranean, https://connectedmediterranean.weebly.com/greedy-beggars-or-pious-missionaries.html.

McSorley, Joseph. “St. Basil the Great.” The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1907, https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02330b.htm.

“St John’s College MS. 208.” Medieval Manuscripts, https://medieval.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/catalog/manuscript_12208.

Soergel, Philip M. Wondrous in His Saints: Counter-Reformation Propaganda In Bavaria. University of California- Berkley Press, 1993.

Willem van Asselt, et al. Iconoclasm and Iconoclash: Struggle for Religious Identity. Brill, 2007.