One of codicology’s more intractable problems thus far has been to determine and compile collation data for the Hargrett Hours. We have been documenting: (1) the number of quires, (2) the composition of those quires and (3) whether anything we would expect, based on the ‘normal’ quire, is missing or different. From almost the very beginning, however, those areas began to merge into the following question: “What the heck is all this tape doing in the manuscript?”

There are three quires—III, X and XII—that are held together, in some way, by tape. We divided up the manuscript between the three group members and David has been responsible for dealing with the ‘artificial quire’ in the section that we now know, thanks to Group 2, is the Hours of the Passion. Here, we find that there is a ton of weirdness going on. The calendar makes up the first 12 folios and the first quire. It seems to be complete even though the front folios have significant fire damage. After the calendar, there are two quires made up of a single bifolium each. The first of these quires is a folded sheet, but the next quire is an “artificial bifolium.” This artificial bifolium is intriguing because it is held together by tape, and we have to determine why they have been placed together.

These two quires contain evidence that there are chunks of the book missing, The front page of both quire II and III have offsetting on them which indicates there are missing pages with borders. Offsetting happens when ink from one page bleeds onto the page across from it. The offsetting on these pages is evidence that there are decorated pages missing. This leaves us with the question: “Where are these missing pages and why are they gone?”

There are two possible theories that David has been working with to explain the missing folios. The first theory is that these pages may simply be missing because they were too damaged to be placed in the rebound book. This theory works as the book has both sustained fire damage and has been rebound. The second theory is that somewhere along the way pages were intentionally removed for sale or individual use. Pages were often removed from books because they were easy to steal and sell individually. This could explain why there are no miniatures in the book and why the hours of the virgin might be missing. If this theory is true, there may be some hope in tracking down the missing folios.

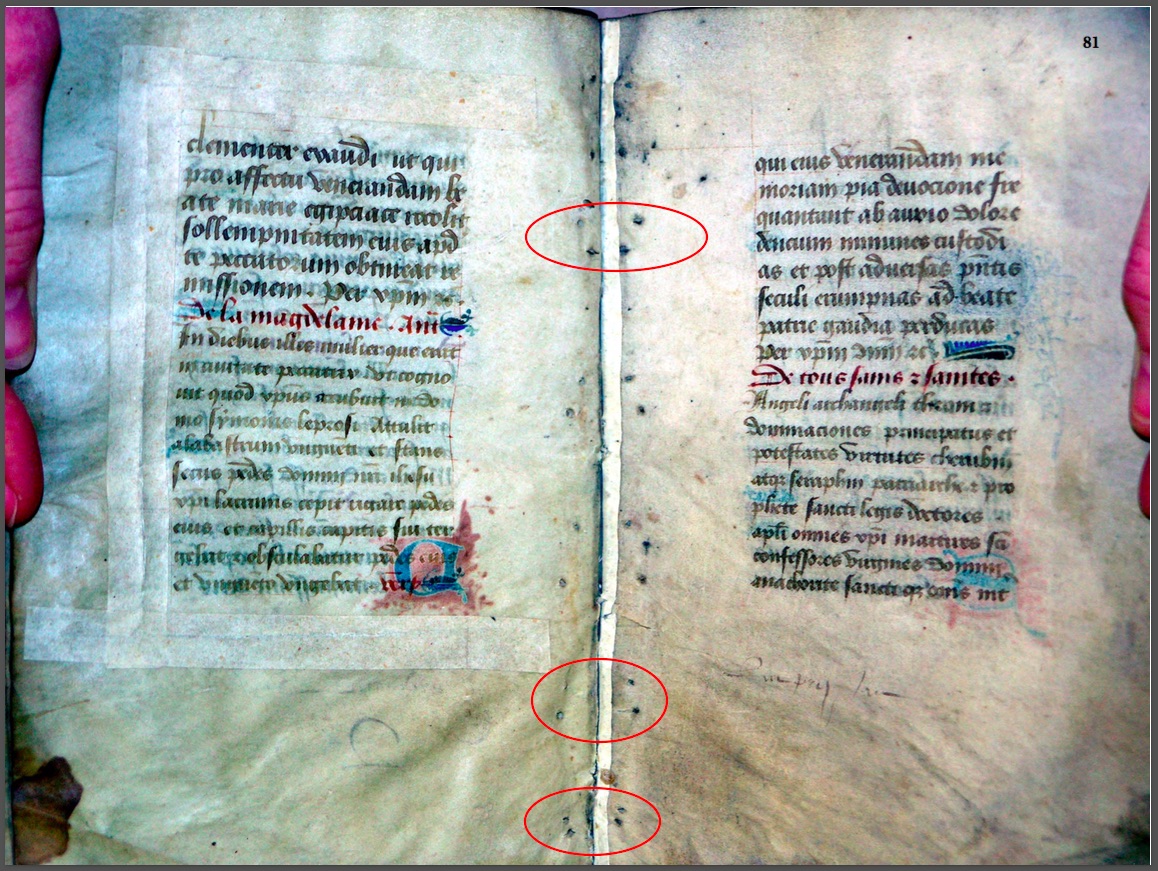

Out of the two taped quires in the final third, Ty has been focusing almost entirely on XII, which falls at the end of the books’ suffrages. While the other wonky quires were at least composed of an even number of leaves, XII has only seven, turning the task of collating into a game of ‘hunt-the-missing leaf.’ Going into to his first solo session with the manuscript, Ty had (what he thought was) a solid theory about where the leaf might have been, based on the facsimile alone. Even on the scan, you can see that the binding holes from f. 80 to f. 81 do not match up as clearly as they do on other pages:

The other piece of evidence to draw from these two pages is the extensive tape that is on 80r. Based on this and on similar, less-extensive damage to the previous page (f. 79), Ty made the tentative guess that a leaf between 80 and 81—call it 80a—had been carelessly mutilated to remove some important feature—likely a decorated border—and then discarded during a later rebinding.

But, alas, problems with this theory began to crop up during a closer in-person, physical examination. While the tape in the binding does in fact support the missing 80a theory—it seems to hold together the quire’s central bifolium, ff. 81-2 and the following leaf, f. 83—Ty’s first close examination of the binding made him think that it was the outer bifolium that was missing a leaf. Looking down the spine of the quire reveals that the quire’s (and manuscript’s) final leaf is free-standing.

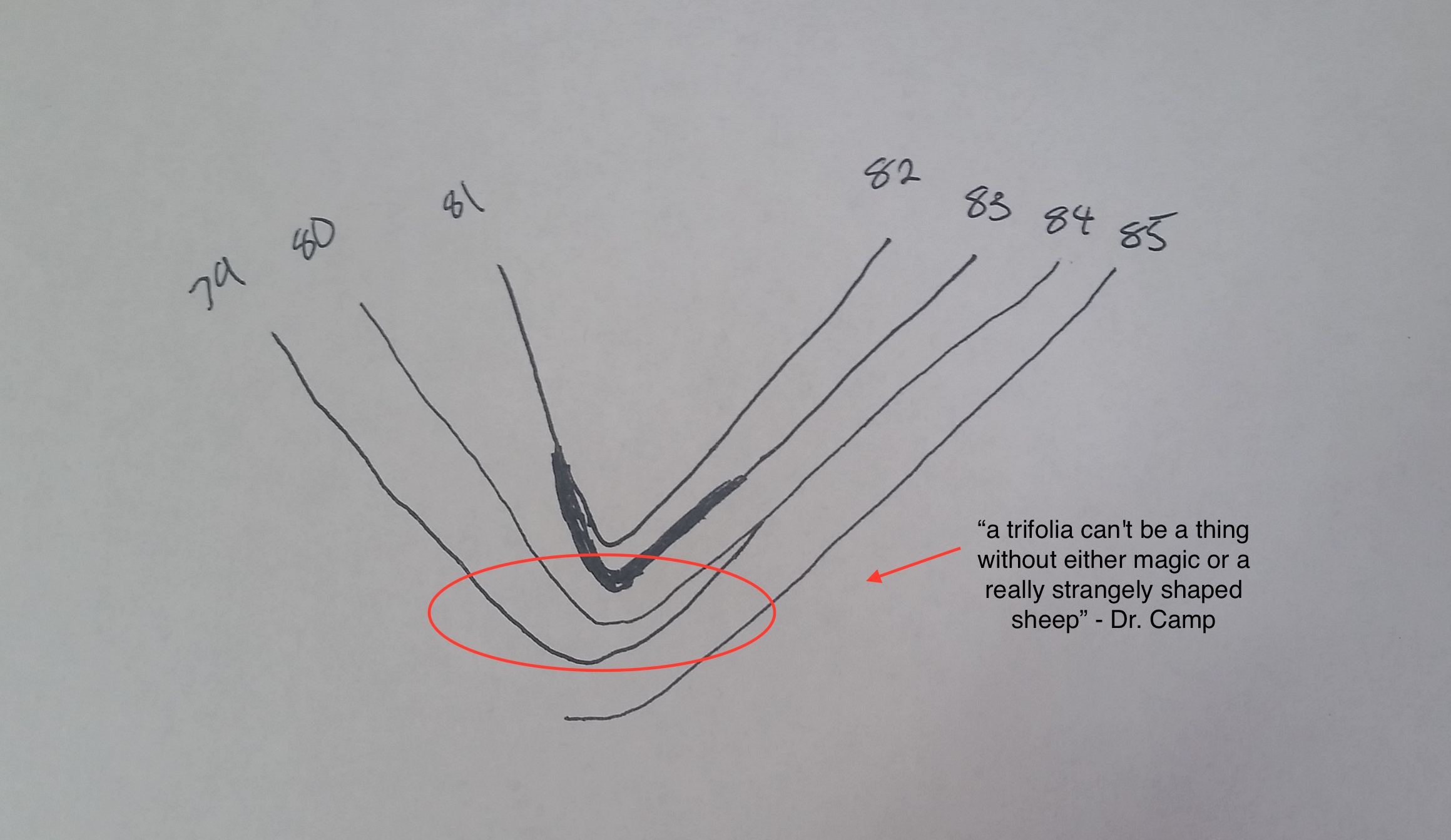

Or at least that’s what it looked like. But a second look with another pair of eyes (Dr. Camp’s) raised problems with this thought. If there is a missing leaf at the beginning of the quire AND the tape creates a trifolium, the math says that the other three leaves must be stuck together somehow. For example:

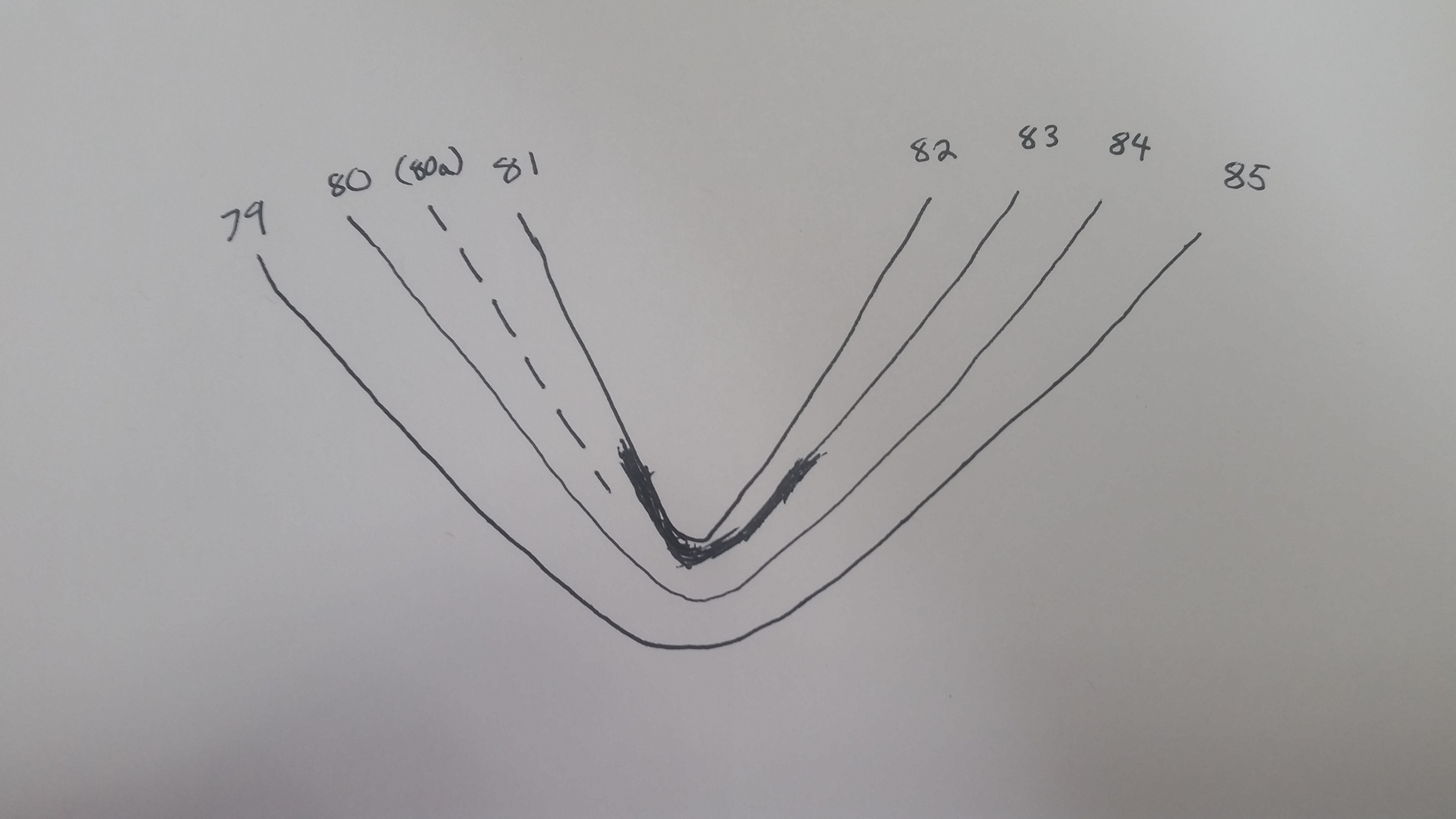

Fortunately, Ty and Dr. Camp, after a closer examination, decided that f. 85 is not, in fact, a single leaf and that it is only superficially detached from 79 at the top of the manuscript. This means that the original theory about 80a being a missing leaf, once again, became the strongest theory. The diagram below illustrates our current state:

Unfortunately, there is still one major problem. Everywhere else in the HH, where we have a border or we think a border was removed, there is extensive residue, as David has observed in his section. (See ff. 15-16 and 18-9 for an example of each case.) So if there was once a border on 80a, why is there no offsetting on 81r? As of now, this question remains unanswered and awaits the opinion of scholars more informed in the field of book binding.

Ty Stewart and David Zeagler for Group 5 (edited by Miranda Clay); professional-looking and clearly-not-just-hastily-scribbled diagrams by Ty.