Introduction

Chances are, you’ve probably never been inside the caves of Afghanistan. But if you’ve gone caving in the video game Minecraft, you might have encountered a nifty and rare ore called lapis lazuli. Congrats, that’s +6 enchanting points.

Unfortunately, we don’t live in Minecraft creative mode. Just like in the game, lapis lazuli was perhaps the most revered and rare pigment in medieval times, yielding a deep ultramarine blue (Cennini 36). Not everyone could afford lapis because it was so expensive to mine and import from the Middle East (Howard 27). The shade of blue produced from this lavish rock is called ultramarine – meaning “beyond the sea” (Clemens and Graham 32). It had to come from far away, or as some might say, from another biome.

Humans are innovative, so it’s no surprise a shortcut for this rare pigment was found. Azurite (also in Minecraft if you’re a serious gamer who uses mods) was a cheaper rock found locally in Europe that yielded the same ultramarine-like shade as lapis. It was completely indistinguishable unless heat was applied to it, making the azurite pigment subsequently turn black (Thompson 131). Azurite was also the preferred source for a blue pigment, as it was simple to make (Thompson 132). So, how do we use the azurite mineral to make this amazing ultramarine-like color? Grab your torches because we’re digging deep!

Making Azurite

In Dr. Camp’s medieval manuscript class, we were able to channel our inner crafting skills to make azurite pigment. After we reconstructed an azurite recipe from three sources, following it was simple. For the first source, we used Medlej’s “Washing Cinnabar” technique from Inks & Paints of the Middle East, as the main outline for our process (51). The second source was a medieval recipe referenced in Clarke’s The Crafte of Lymmyng and the Maner of Steynyng. From this recipe, we got the idea of using vinegar to wash our azurite (Clarke 85). Lastly, the third source was used as a reference to confirm that the shade of blue we created, should be “ranged from dark denim blue to a slightly green-grayish blue” (Parks 13). In all, we learned about grinding and washing our pigment. These techniques will be prominent as we explain the process of following our reconstructed recipe.

We started making our azurite pigment by gathering our materials and ingredients. With a 7.17g of raw azurite at hand, we used the brass mortar and pestle to start the grinding process. Matt was at it, using a circling motion to get the azurite down to particles. As he was doing this, we were aware of one tip from our research: the tone and hue of azurite can be easily changed based on how finely ground the particles are. The coarser the particles, the more the pigment would lean towards dark blue, while the finer the particles, the more pale greenish/blue it will yield (Howard 42; Thompson 131-2). What a nice crafting tip!

After we had ground the azurite into a powder, it was time to wash our pigment. First, we moved from the brass to the ceramic mortar, where we added about a teaspoon of vinegar to the azurite powder. Then, the only steps left were to grind the powder, let the mixture settle, pour the dirty vinegar out of the mortar and into the jar, and repeat the process until the vinegar was clear. It is important to note that we were only pouring the liquid, not the sediments out of the mortar (Medlej 51). What is collected at the bottom of the jar would be our pigment.

There were 6 rounds of washing the azurite powder until we finally poured out the last of the dirty vinegar. Now it was time to let it dry. After days of sitting in Dr. Camp’s window, the pigment dried to a nice ultramarine hue that we were able to try out on Pigment Testing Day.

It is important to note that the resulting pigment was not quite as dark as we might have expected. The pigment was quite grainy and not the best for painting, likely because we did not grind it finely for fear of making the pigment too light. Despite this, we still had a rich blue color that could be compared to our third source and to some of the examples we had examined in the manuscripts. We had successfully made azurite, like many medieval artists (or illuminators) before us.

Looking through Manuscripts

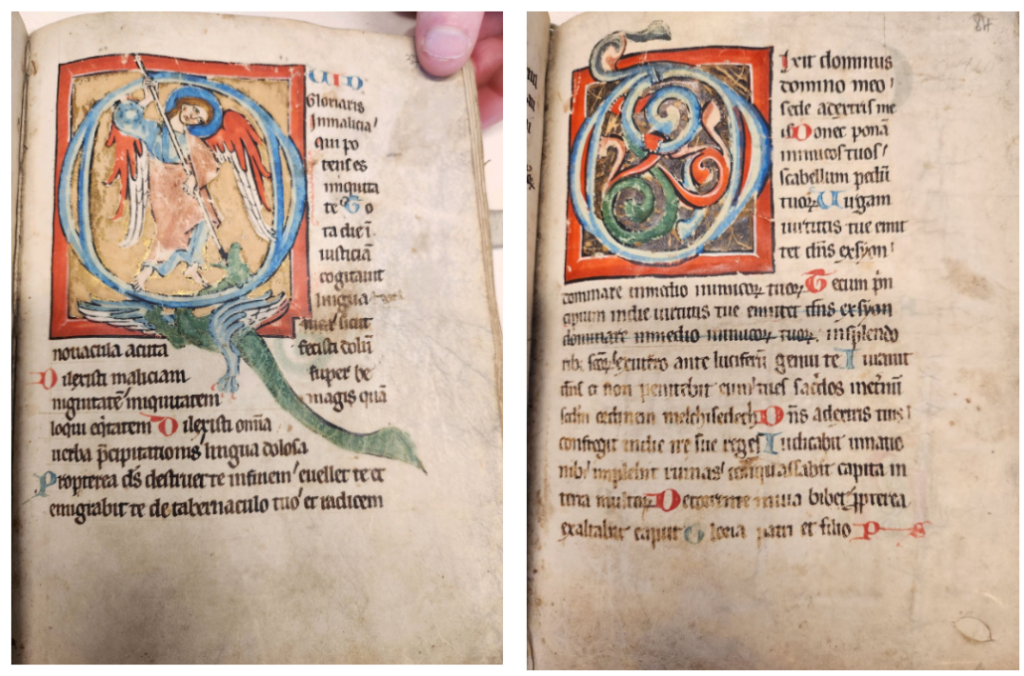

Azurite pigments can be found in many manuscripts, but what does azurite actually look like in one? In the image on the right, taken from The Alphonso or Tenison Psalter, the blue background of the folio presents a strong blue that has been confirmed to be azurite by the Teaching Manuscripts website. What a catch! Azurite is already hard to differentiate from lapis lazuli, so this was a great example to compare with the pigment our team made.

Along with this manuscript, we took the time to examine other blue pigments in another manuscript. One day, our manuscript-making class had the opportunity to get a closer look at how certain manuscripts used the shade of color we worked on. In this case, our team looked for azurite. We had the opportunity to see if we could get a good comparison between the folio we found online (mentioned above) and the pages we looked at in person. The manuscript we chose to examine was the Constance Psalter from southern Germany:

Knowing, thanks to Dr. Camp, that the blue pigment’s origin is a mystery, it was thrilling to see the shades of blue up close. There was no telling if the blue in the manuscript was intentionally made to be a pale blue or if it was a pigment that had slowly faded over time, but this was a blue that we could relate back to our experiment. As previously noted, azurite can range in many shades of blue based on the particle size (Howard 42; Thompson 131-2). So, from the lightest shade of the letters to the darkest rim of coloring on the initials, they all could be azurite. The darkest shade presented even looks like the azurite blue in the Alphonso Psalter. Now, this is what we’d call a thought-provoking way of looking at a manuscript!

Conclusion

After creating and applying our azurite pigment, this pigment turned out to be a convenient success. The pigment was a suitable substitute for the expensive lapis lazuli: the process of making the pigment was straightforward and materials could be sourced from anywhere. As it turns out, you do not need to explore the caves of Afghanistan for this ultramarine hue. You don’t even need to enter the Minecraft realm just to get azurite. Azurite will always be abundant and easy to make, imprinted in the many manuscripts and recipes throughout history. Empty your inventory because now it’s your time to get digging!

Works cited

Cennini, Cennino. The Craftsman’s Handbook. Courier Corporation, 1954.

Charles, Sarah. “Azurite.” Teaching Manuscripts, 2020, https://www.teachingmanuscripts.com/azurite.

Clarke, Mark. The Crafte of Lymmyng and the Maner of Steynyng : Middle English Recipes for Painters, Stainers, Scribes, and Illuminators / Edited by Mark Clarke. First edition., Published for the Early English Text Society by the Oxford University Press, 2016.

Clemens, Raymond, and Timothy Graham. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Cornell University, 2007.

Howard, Helen. Pigments of English Medieval Wall Painting. Archetype, 2003.

Medlej, Joumana. “Washing Cinnabar.” Inks & Paints of the Middle East: A Handbook of Abbasid Art Technology, Majnouna, London, 2021, p. 51.

Parks, April. “To Make_Many_Pigments_Jorhildr.” Heraldry.Sca, 2017, https://heraldry.sca.org/kwhss/2017/To_Make_Many_Pigments_Jorhildr.pdf.

Les Enluminures, TM789. https://www.textmanuscripts.com/medieval/medieval-german-psalter-79751

London, British Library Add. MS 24686 https://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx

Thompson, Daniel V., and Bernard Berenson. The Materials and Techniques of Medieval Painting / by Daniel V. Thompson ; with a Foreword by Bernard Berenson. Dover Publications, 1956.

Credits

Team Blue: Matthew Karshna, Nicholas Dietz, Brianna Groves, and Cindy Nguyen

Featured Image Caption: Traveling in the cave for a rare, blue ore. Image by Firecat_the_potato from Pixabay following the (Pixabay License) – “You’ve probably never been inside the caves of Afghanistan. But if you’ve gone caving in Minecraft, you might have spotted a rare, blue ore…”