What to Expect When You Expect Ink

It is easy to get caught up in medieval manuscripts’ vibrant, devotional illuminations. However, one component might get overlooked because of its simplicity: black ink. The most common form of black ink in European medieval manuscripts came from iron gall ink, which was made from oak galls.

Oak galls are small, abnormal formations on the branches of oak trees. Though they appear to be small nuts, similar to acorns, they are actually formed by oak gall wasps. According to the LA County Natural History Museum, when the wasps lay their eggs in the oak tree, their secretions inhibit cell growth, causing a mass to form around the larvae. Once the wasp leaves the gall and the masses form a globular shape, they are harvested and dried for the preparation of ink. It is important to be mindful during harvesting though, because a surprise wasp or two might be hidden inside the galls.

These formations are good for making black ink because they are high in tannins, specifically gallotannin and gallic acid. Gallic acid is a naturally occurring acid that is commonly found in various parts of plants, including bark, wood, leaves, fruits, roots, and seeds. Yes, you may be thinking of wine tannins, and you would be correct. The bitterness of grape skins, pomegranates, wine, and even black teas is due to a high concentration of tannins, and they are the reason for the tight feeling and almost chalky taste in your mouth when you consume these foods. Though you hopefully won’t be drinking iron gall ink, it’s a fun fact to remember.

Iron gall ink has four main components: oak galls, water, gum arabic, and vitriol (an iron salt otherwise known as copperas, iron sulfate, or ferrous sulfate). After you have these base ingredients, the process of making the ink can vary for each step. Some recipes, like the one below, require you to steep crushed oak galls as you would a tea, and this process, depending on the recipe, could ferment anywhere from 12 hours to 2 months. Other recipes turned to the faster method of boiling the crushed oak galls. Either way, the soaking or boiling of the oak galls is necessary for releasing the tannins.

London, British Library, MS Sloane 1201 [#1874], The Craft of Lymmnyng and the Maner of Steynyng

To make ynke Lumbarde. Take an ounce of galles and breke in a morter to pouder, then take an ounce of grene coperose and breke hit in a morter to pouder, and put hem in a quarte of stondying water or reyn water or dyche water, and then take an ounce and halfe of gomme Arabyk, and knytte hit in a lynnen cloth and ley hit in a lytel water tyll hit mylte, and afterwards streyne hit oute and medull hit with thyne inke, and let lit stond a sevenight and it schall be good ink.

Fig. 1: This recipe from Mark Clarke’s The Crafte of Lymmyng and the Maner of Steynyng: Middle English Recipes for Painters, Stainers, Scribes, and Illuminator exhibits the use of steeping the crushed oak galls in standing rain or ditch water rather than boiling it.

As seen in this recipe, the process of making ink had various steps, and recipes could vary from one ink maker to another. Often, measurements were not exact, and recipes were written based on past experiences.

Everyone, Get in Here!

Aside from the four main ingredients in iron gall ink, additives could also be incorporated. Joumana Medlej’s Inks & Paints of the Middle East provides information on different additives that could be used in the process of ink making. Wine and vinegar are cited in many recipes, but these preservatives come with their own issues because they could mess with the pH balance or may contain modern preservatives like sulfites. Many of our medieval references lack preservatives like those cited in the following blog posts. Due to the difference in chemical compositions of modern versus medieval ingredients like wine and vinegar, it is important to research your ingredients and the reactions of combining them before attempting.

While Medlej references additives such as pomegranate rinds, they’re not always necessary. We didn’t use any, and our ink lasted over a couple of weeks in a jar before we were able to test the unpreserved ink.

Our Dip Into Iron Gall Ink

Our recipe combines two different recipes: Jean le Begue’s recipe from Mark Clarke’s The Art of All Colours: Mediaeval Recipe Books for Painters and Illuminators and another from Medlej’s Inks and Paints of the Middle East: A Handbook of Abbasid Art Technology. We altered the recipes slightly to create one appropriate for the modern era. We used the ingredients from the Persian recipe due to its simplicity. We also incorporated all of the ingredients from the medieval recipe that we had access to. Since both the medieval and modern recipes were for a large batch of ink, we reduced our recipe by ⅕. Reducing the proportion of ingredients meant we had to adjust the boiling time because we were using a smaller amount of water and a modern stove top instead of a traditional charcoal fire.

To begin our ink-making process, we weighed out the correct amount of gall nuts, placed them in a Ziploc bag, and crushed them with a rolling pin. In our next step, we measured out the water and began to heat it in a pot on the stovetop. Traditionally, there are two ways to heat this mixture: letting it steep in the sun for a few days or boiling it. While steeping in the sun worked well in an age before gas stoves were invented, we preferred the more efficient method of boiling. We added the gall nuts to the boiling pot and the water turned a light brown from the crushed sediment of the galls. When the crushed galls are submerged in water, gallotannic acid–an acid consisting of a glucose molecule and five gallic acid groups–is released (Eusman, “Iron Gall Ink – Chemistry”). Once the boiling water heats this acid up, it hydrolyzes to gallic acid and glucose. Hydrolysis just means that one larger molecule breaks down into two smaller molecules when it reacts with water. After boiling the galls for a few minutes, we saw a shift in the color when the brown took on a darker hue, becoming a dark brown. After a few more minutes, we added gum arabic as a binder to thicken the ink and help the ink adhere to surfaces when applied. We then took the pot off the stove to let it cool before we added the magic ingredient, green vitriol, a chemical compound with many names.

When the vitriol is added, a pivotal chemical reaction takes place. The iron in the vitriol reacts with the tannins in the gallic acid, changing the color of the mixture from brown to black instantaneously! This is because when the gallic acid reacts with the iron, they form ferrous gallate which is black in color (Tohma, “Making & Testing Iron Gall Ink”). Once completely mixed and cooled down, we strained the ink with a cheesecloth and strainer over our container. Then, we were left with our ink!

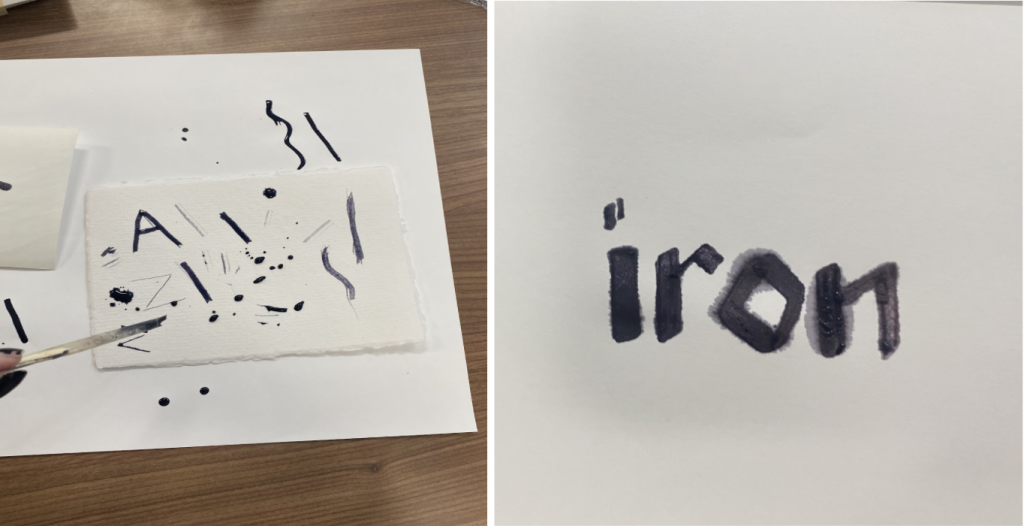

After a few weeks, we tested our ink. Upon initial application of it, the ink appeared light and gray, but when the ferrous gallate reacted with the oxygen in the air, the ink oxidized and gradually turned darker until it became black, as shown in the images below. The ink maintained its rich color. However, it bled on the printer paper and collected into droplets on the artist’s paper and parchment. Our ink’s inconsistency could be due to the weeks we left it to sit or because our paper/parchment wasn’t prepared properly. Despite this imperfection, we were able to doodle and have some fun with our ink. Hopefully, if any of you have the opportunity to try to make some too, you learned a little bit from us.

The process of making iron-gall ink was definitely a journey, but we learned a lot along the way. Even after all of our research and effort, our ink did not come out perfect. It really put into perspective the precision and skill that it took to make ink that could last on a page for centuries!

Works Consulted

Banik, Gerhard, et al. “The Iron Gall Ink Website.” Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed, 13 Feb. 2011, https://irongallink.org/home-the-iron-gall-ink-website.html.

Clarke, Mark. The Art of All Colours : Mediaeval Recipe Books for Painters and Illuminators / Mark Clarke. Archetype Publications, 2001.

Clarke, Mark. The Crafte of Lymmyng and the Maner of Steynyng : Middle English Recipes for Painters, Stainers, Scribes, and Illuminators / Edited by Mark Clarke. First edition., Published for the Early English Text Society by the Oxford University Press, 2016.

“Commentary on Peter Lombard’s First Book of the Sentences, Related to Paulus Venetus, Super Primum Sententiarum Johannis De Ripa Lecturae Abbreviatio.” Lombard Sentences Medieval Manuscript : Medieval Text Manuscripts, https://www.textmanuscripts.com/medieval/peter-lombard-sentences-60624.

Eusman, Elmer. “Iron Gall Ink – Chemistry.” The Iron Gall Ink Website, 1998, https://irongallink.org/iron-gall-ink-chemistry.html

Higgins, Lila. “Oak Wasp Galls.” Natural History Museum, 13 Oct. 2013, https://nhm.org/stories/oak-wasp-galls.

“Hydrolysis.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/science/hydrolysis

Karnes, Cyntia. “The Iron Gall Ink Website.” Irongallink.org, 2011, https://irongallink.org/how-to-make-ink-ingredients.html.

Medlej, Joumana. Inks and Paints of the Middle East: A Handbook of Abbasid Art Technology. Majnouna, 2021. Accessed 16 September 2022.

Peverly, Sarah. “Iron Gall Ink: A MedievalRecipe.” Sarah Peverly, https://sarahpeverley.com/2014/01/29/iron-gall-ink-a-medieval-recipe/.

“Tannin.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/science/tannin.

Tohma, Sakura. “Making & Testing Iron Gall Ink.” West Dean College of Arts and Conservation, 10 Mar. 2015, https://www.westdean.org.uk/study/school-of-conservation/blog/books-and-library-materials/making-testing-iron-gall-ink

VinePair. “What Is a Tannin? A Guide to Tannins.” VinePair, 11 Oct. 2022, https://vinepair.com/wine-101/guide-to-tannins/.

Authors: Ansley Murdock, Hannah Rieder, Luna Jenkins, Zoe Alvarez

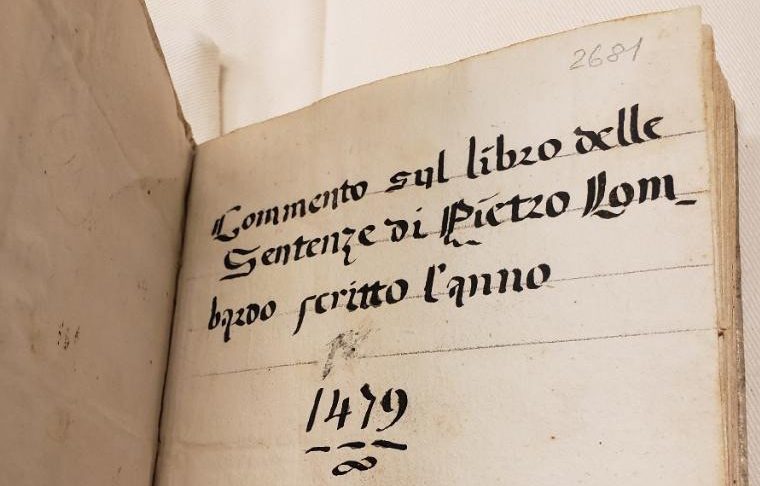

Featured Image Caption: This is the title folio from the manuscript Commentary on Peter Lombard as referenced in our works consulted section above.