If you want to get a glimpse into the life of a medieval lay person, there’s no better way to do it than to open a book of hours. Both a prayer book and an object of art, it was a central part of any fairly literate person’s daily devotion. Let’s take a look at one fine example of the most widespread genre of medieval manuscripts, originating from Southern Netherlands.

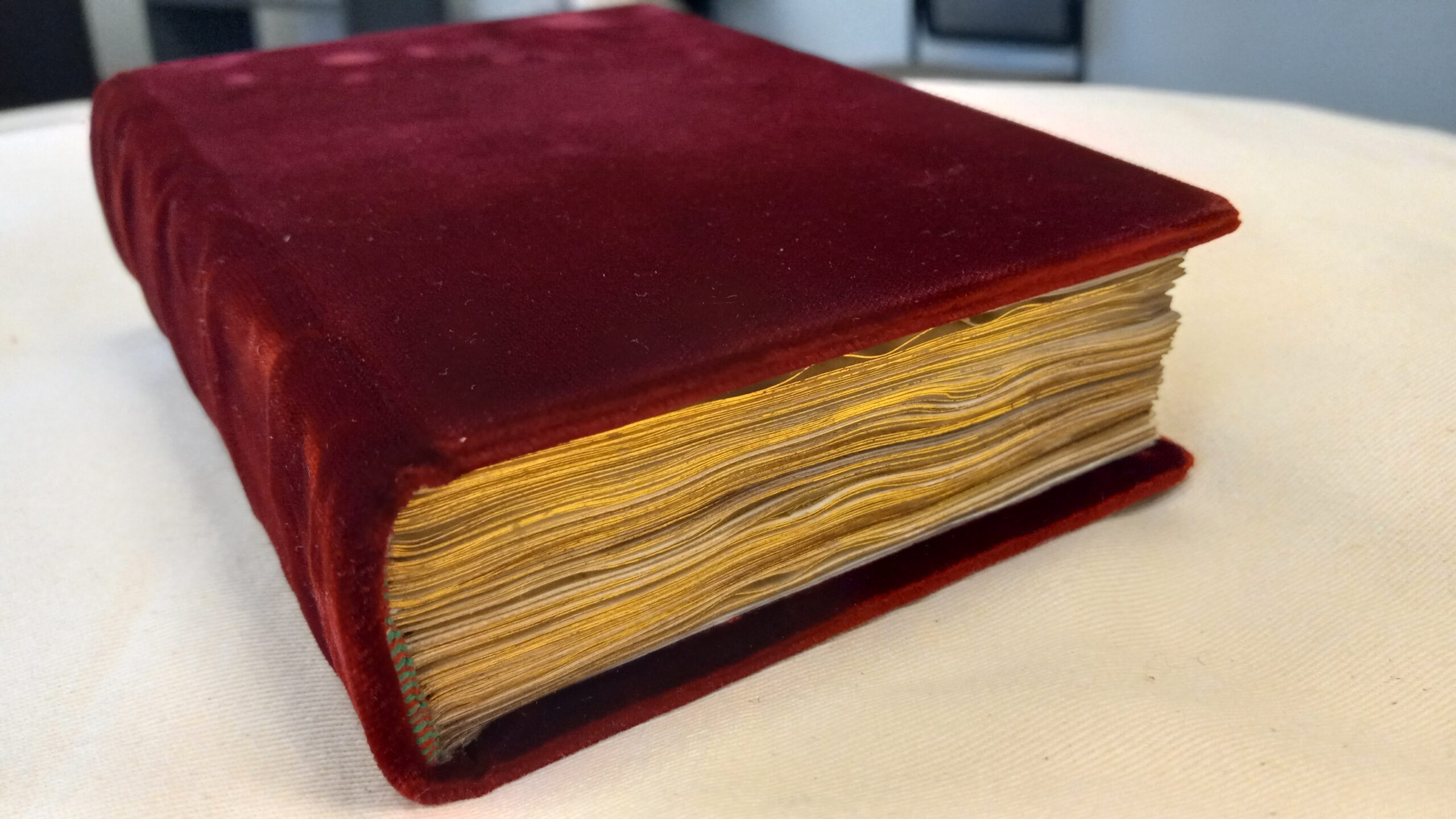

Although the red velvet binding is comparatively modern, its rather thick vellum folios date back to c. 1480 and still have that distinct parchment crispness when you leaf through them. It’s quite easy to navigate these 105 leaves written in rather legible gothic hand if you know a few tricks and Latin. Let me break down the tricks for you before you indulge in language studies.

The first trick is to know the structure. The book opens with a calendar prompting the medieval person what saint should be venerated each month. Although this one is missing its September/October leaf, the saints on other leaves of this section helped to localize the manuscript to Ghent/Bruges. The calendar follows with Short Hours of the Cross and the Holy Spirit focusing on the crucifixion and redemption. While these two were for everyday use, the Mass of the Virgin that comes after was referred to only on Saturdays during the service at church.

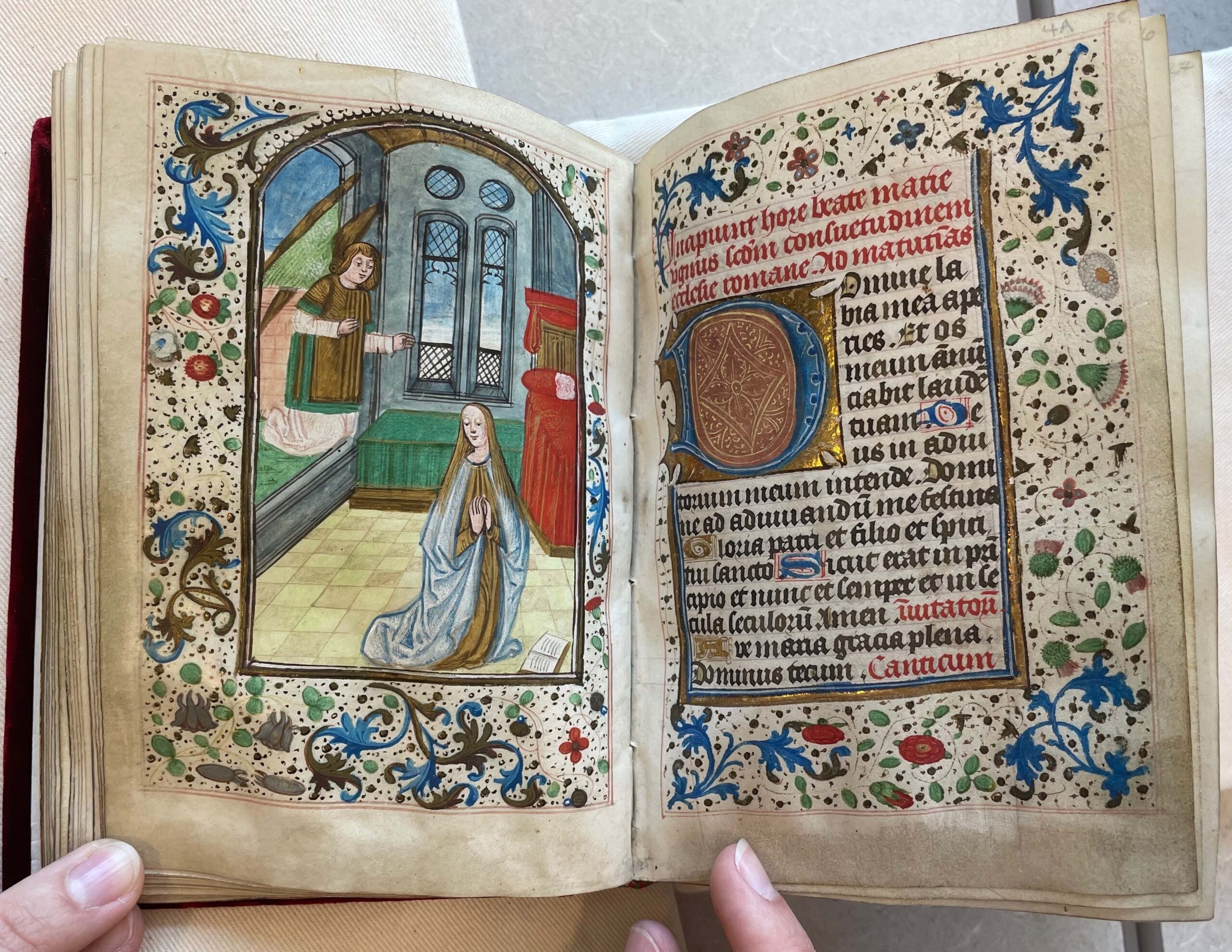

Next come the Hours of the Virgin – the heart of this book, giving the genre its name. Compiled in accordance with ‘proper’ religious practice, this secular version of daily devotion is divided into 8 parts, containing prayers to be said at certain times of the day. Fun fact: the prayers are not written in full, because saying them daily one would definitely remember them, but not necessarily their exact order.

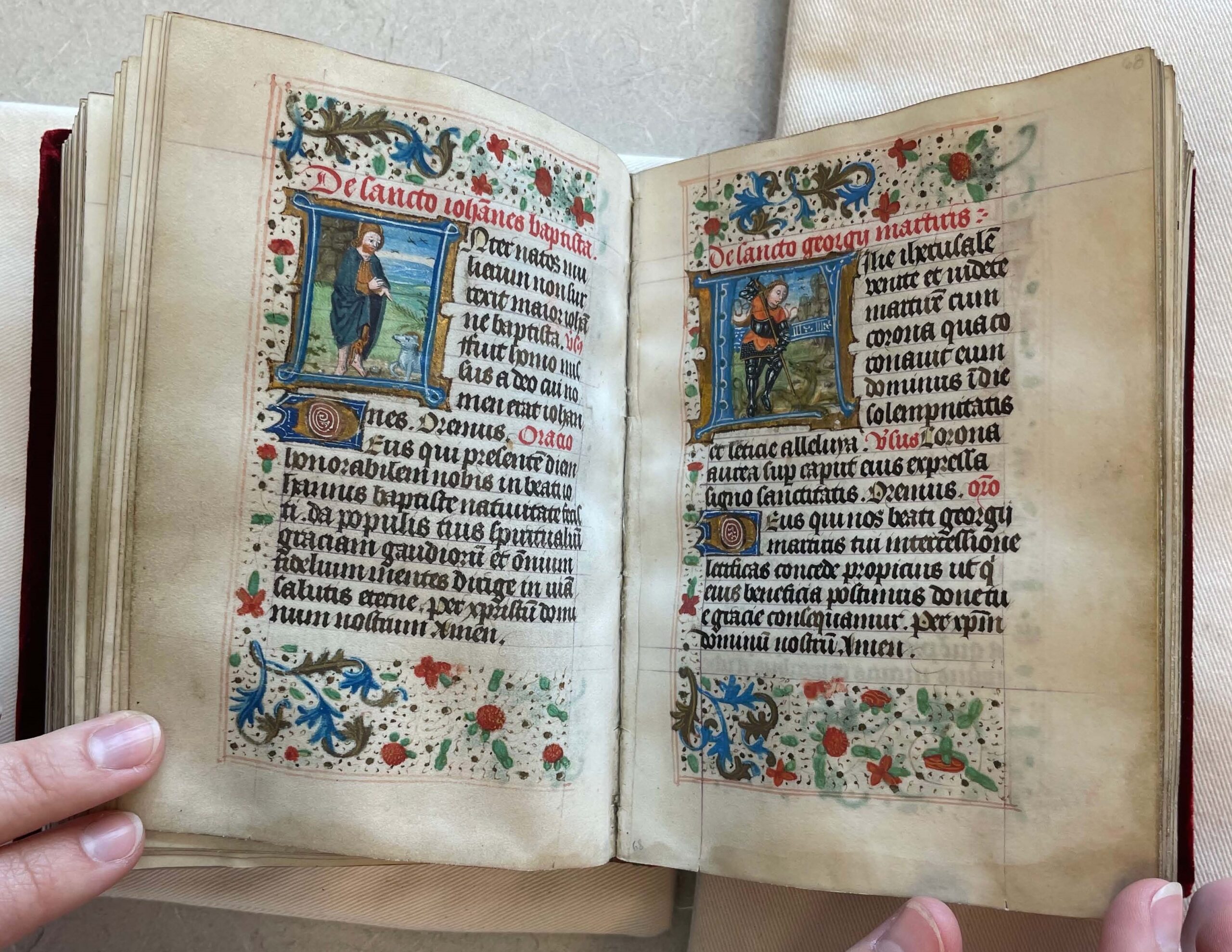

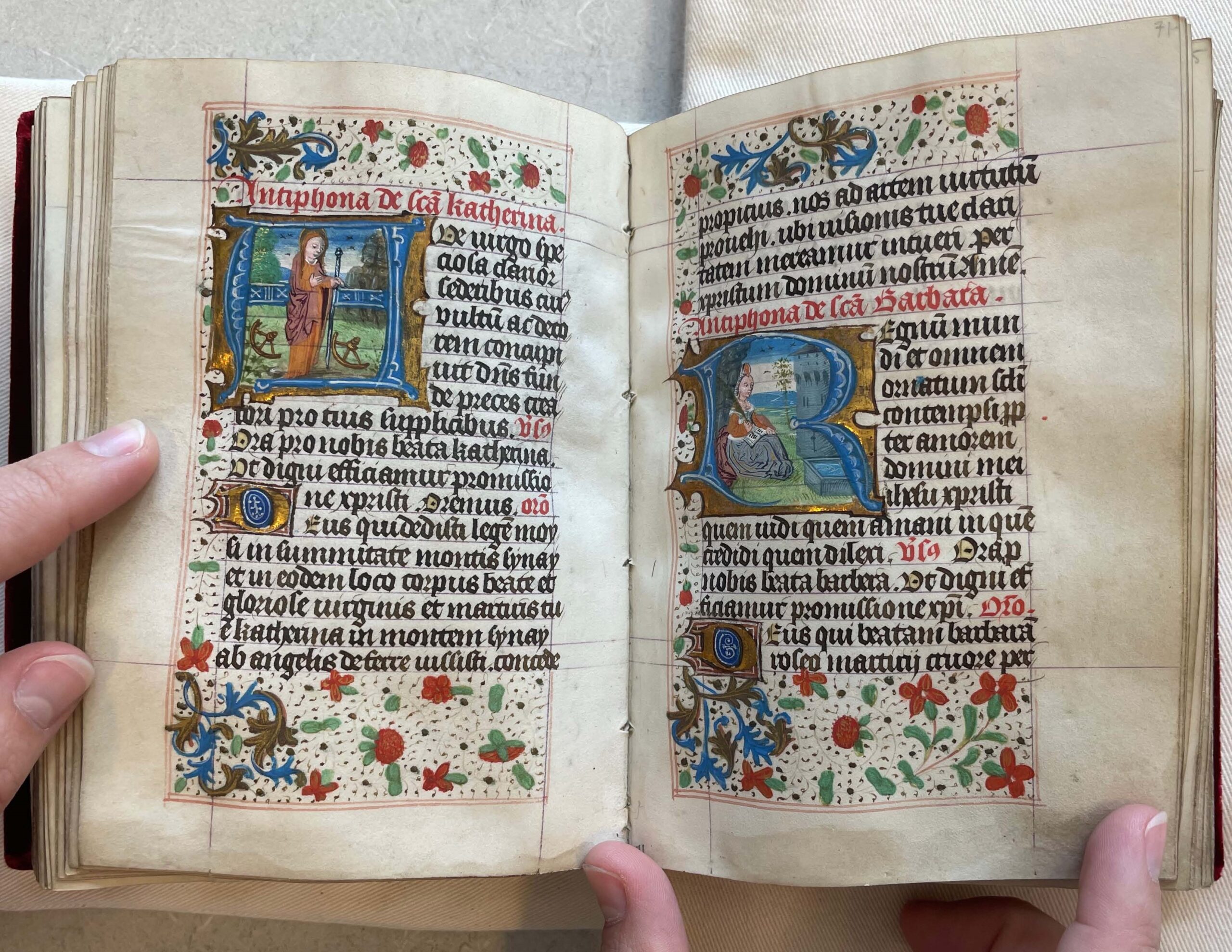

In addition to this, the book contains a set of prayers the owner could resort to in the time of need. These are Suffrages – the most variable part within this genre, as the set of saints, whose help a person might seek, was accommodated individually. While some outstanding books of hours included over one hundred saints, this specimen has a regular number of seven: Archangel Michael, John the Baptist, Saint George, Saint Anthony, Saint Christopher, Saint Catherine and Saint Barbara. This section is among the most richly decorated ones, see for yourself.

The Penitential Psalms (linked to the Seven Deadly Sins) and Litanies come next. As the list of saints mentioned in litanies is followed by petitions requesting deliverance from all evils, sins and eternal damnation, the following text, the Office of the Dead, brings a logical closure to the book of hours.

The next trick to learn is the purpose of illustrations. Miniatures and historiated initials not only help quickly find the chapter you’re looking for, serving as a bookmark, but also help tune the reader into a meditative mode fit for a prayer. Three hands worked on the decoration of this manuscript: a Dutch-influenced artist did the Coronation of the Virgin, a Flemish one painted the rest of miniatures and the third hand intervened to do the initials in the suffrages with exceptional sophistication. Can you tell them apart?

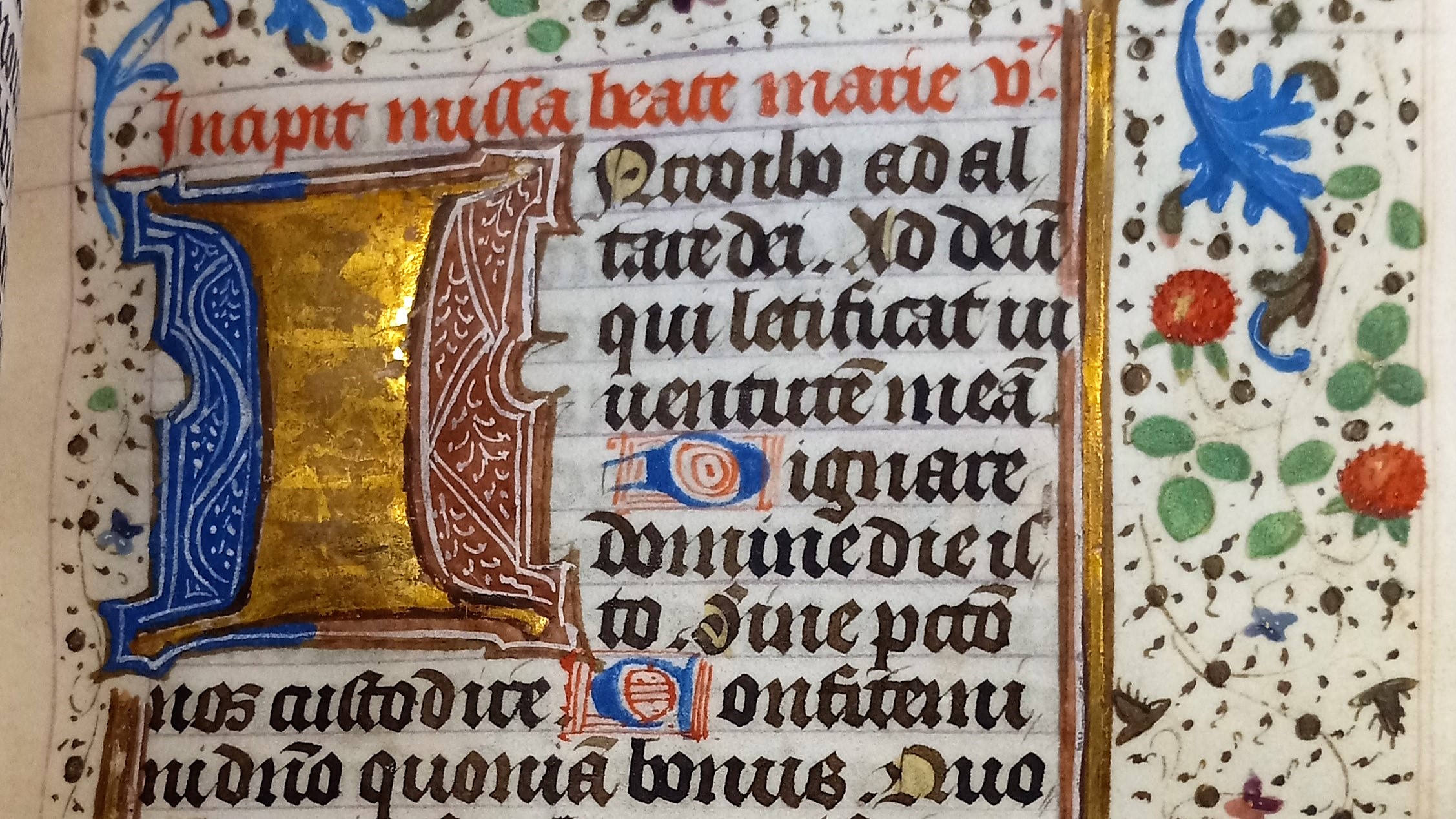

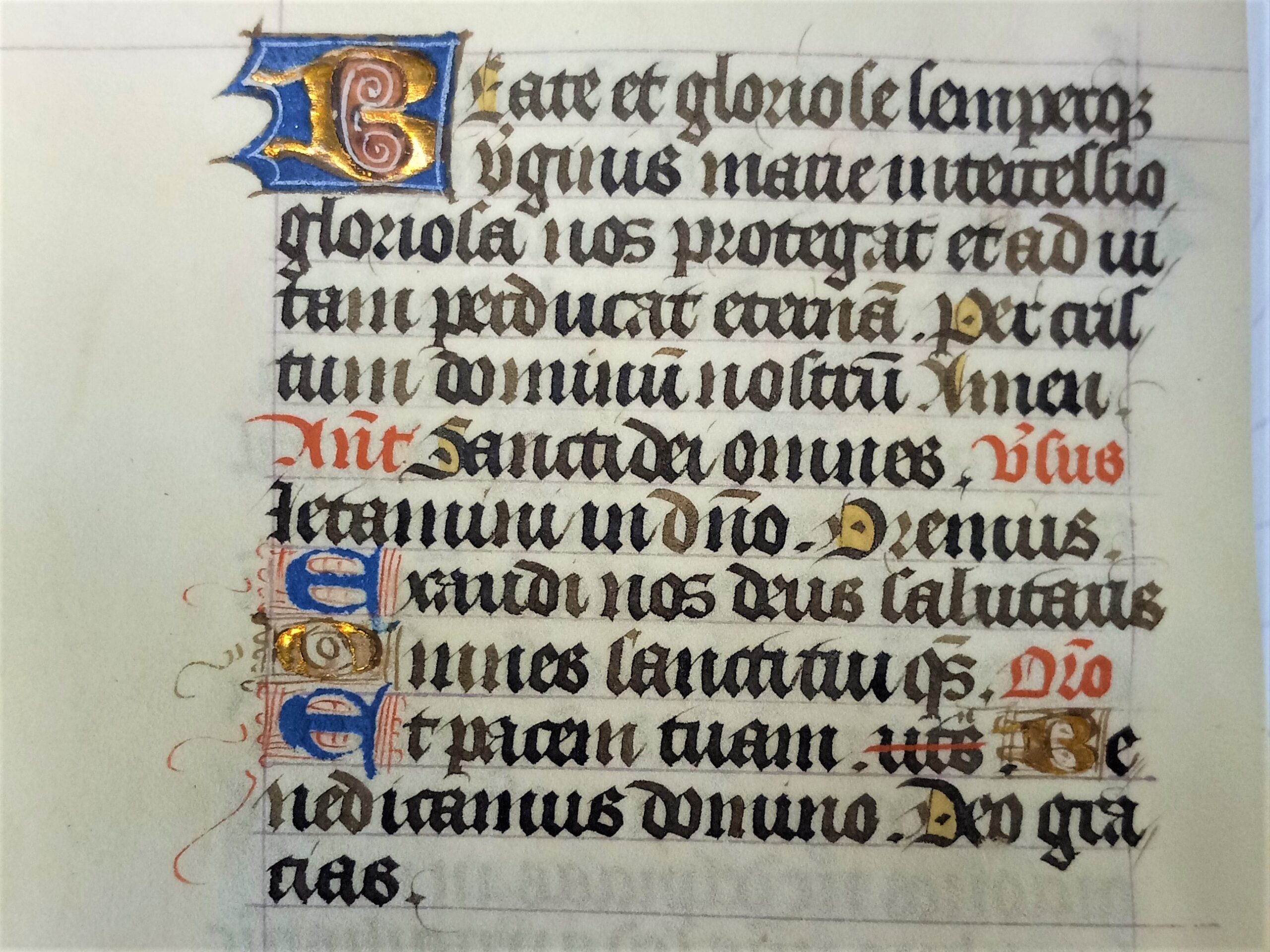

The final trick concerns the initials: 21 large initials (seven or six lines high) mark main sections and are accompanied by a border decorated with acanthus, fruit and burnished gold ivy leaves (fig. 2). The Offices and each of the Suffrages open with a seven-line initial, while six-line ones separate the sets of prayers in the Hours of the Virgin. Two-line and one-line gold and blue initials with elaborate penwork help navigate through smaller sections of the text. The former initials introduce hymns, psalms, chapters, and prayers; the latter designate verses and responses, as well as each new sentence within hymns and psalms. And finally, in line with user-friendly approach, the beginning of each sentence that doesn’t fall into any of the above mentioned categories is given a touch of yellow.

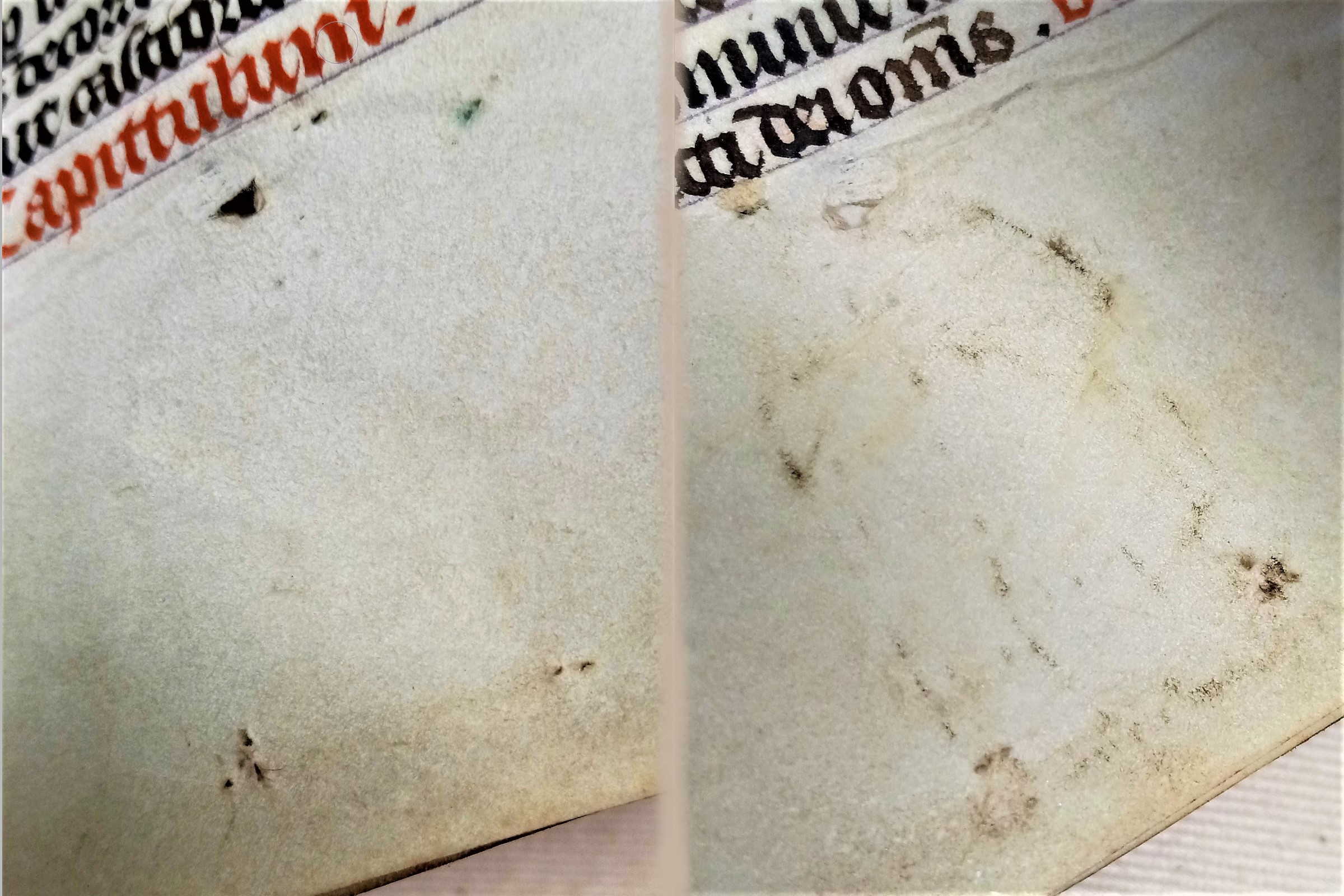

As pages in the book of hours didn’t have numbers, decorators had to provide the reader with visual cues (miniatures and a variety of initials) to make it easier to find necessary section. Moreover, the owner would also step in and adapt the book to their needs. In this case, traces found on the bottom margin of the end of “Nones” section of the Hours of the Virgin point to the pilgrim’s badge, used to bookmark the Vespers – early evening prayers. Metal residue and impression of an arch-like frame and silhouette resembling Mary and the Child together with sewing holes reveal the former presence of the badge. Despite its name, the pilgrim’s badge would not always imply that the owner of the book went on pilgrimage, as it was common to buy them from local craftsmen or travelling merchants, or even receive it as a gift. Attached to the page, it facilitated looking for prayers essential for daily devotion and helped the owner to picture themselves in front of the statue, thus completing the mental pilgrimage. Together with the opening featuring The Annunciation miniature, this former presence of another depiction of Mary within the Hours of the Virgin testifies to inseparable connection between image and text in devotional use of books of hours.

Featured image: opening of the Mass of the Virgin (BOH 159, f. 14r)

Works Consulted

Clemens, Raymond, and Graham, Timothy. “Books of Hours.” Introduction to Manuscript Studies, Cornell University Press, Ithaca & London, 2007, pp. 208-221.

Reinburg, Virginia. “Prayer and the Book of Hours.” Time Sanctified : The Book of Hours in Medieval Art and Life, edited by Wieck, Roger S., et al., 1st ed., G. Braziller in association with the Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore,1988, pp. 39-44.

van Asperen, Hanneke. “The Book as Shrine, the Badge as Bookmark: Religious Badges and Pilgrims’ Souvenirs in Devotional Manuscripts”. Domestic Devotions in the Early Modern World. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004375888_016 Web.

Les Enluminures, BOH 159, Book of Hours (Use of Rome?)