Let’s talk reds. Bright, vibrant, and usually toxic – reds were one of the most important pigments for any medieval manuscript.

Hi, we’re Team Red, and our task this semester was to survey the different sources of red pigment used in medieval manuscripts and adapt some medieval recipes to actually make the pigments ourselves. But don’t worry, we didn’t make the toxic ones.

I know what you’re thinking: What?? Medieval illuminators used toxic paints?

Yes, and they knew it, too! Red lead was an extremely popular pigment in medieval manuscripts. Why did medieval artists love to use this deadly metal to make pigments? Well, it was extremely bright and maintained its red hue undeniably well! Plus, the process of heating white lead, the result of suspending lead over acid, was simpler and less expensive than alternatives for making red pigment.

With this in mind, we decided to make a less toxic alternative which, to the naked eye, is almost indistinguishable from the famed red lead. Cinnabar, a naturally occurring compound of sulfur and mercury found in mines and around volcanoes, was a worthy second choice because it still offered a nice, deep red color. It does have a synthetic twin pigment called vermilion (they produce practically identical shades of red); however, to create vermillion means to use unadulterated mercury in order to synthetically combine it with sulfur. That makes vermillion extremely toxic to produce and use – which obviously means the medieval artists loved it (lol!). It was frequently used as a substitute for cinnabar because it was much cheaper to source and produce. But, both cinnabar and vermilion, like red lead, usually produce a vibrant red like the color we see in this Office of the Dead (which could be red lead or cinnabar or vermillion):

After deciding which red pigment to attempt, we chose a process to follow and began our experiment. Our first step to turn this compound, which looked like a reddish-purplish lava rock, into a pigment was to grind it into a fine powder. We trained at the gym for weeks before the day came to grind… or maybe we should have. Using a small mortar and pestle to grind up a literal rock is no joke. (Our friends in Team Green agree, and you can read through their green pigment journey [here].) Eventually, we decided our powder was fine enough and started washing our ground stone . The washing process was fairly simple: swirl the powder with water, let the particles settle, pour the watery mixture into a jar, and repeat, using separate jars, until no silt remains.

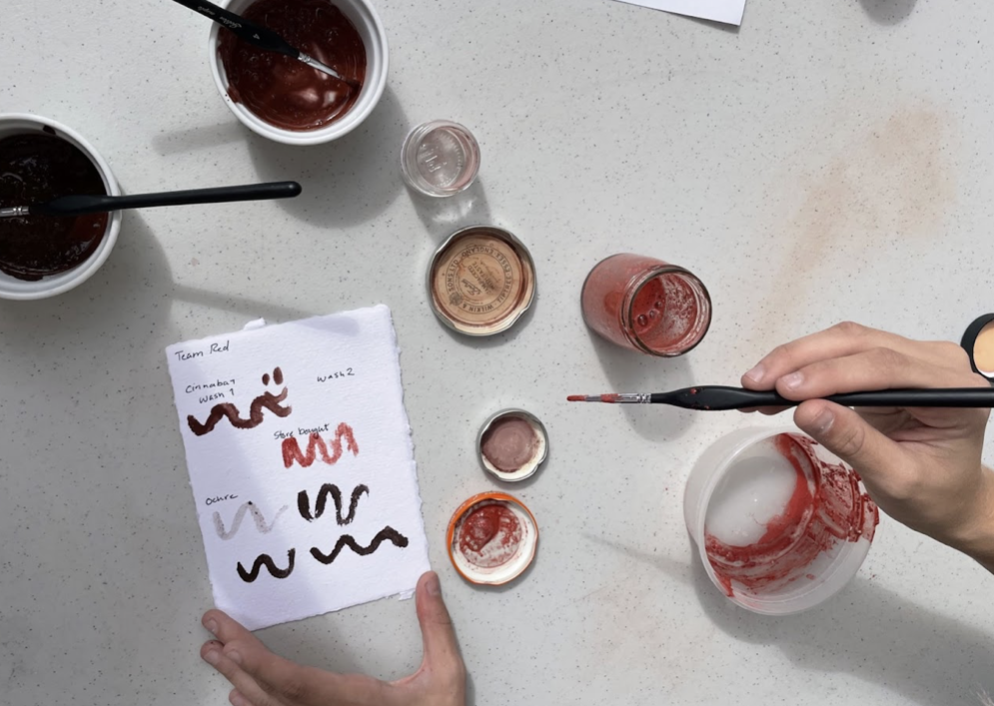

This washing step is important because it does exactly what it means: it cleans the pigment. Here’s a great comparison between a “wash” of pigment and the pigment still waiting to be washed:

We washed and washed and washed. And washed some more. Then we set our pigment jars on a window sill to dry, anticipating brilliant red results.

Don’t count your chickens before they hatch…

The day finally came to test our little batch of cinnabar. Hooray! We mixed our dried powder with a medieval pigment binder called egg glair, which is made from whipped egg whites. Binders, as the name suggests, hold pigments together, and egg glair was very popular with medieval artists considering how easily accessible and inexpensive eggs were, and still are. After mixing the two into a semi-smooth clump of paint, we tested our made-from-scratch pigment!

No, no, don’t get excited. That bright red you see on the right side of our test page is the store-bought cinnabar pigment. See that little smiley-face guy and the maroon-y brown streak of paint in the top left? Yep, that’s ours. We’ll read your mind right now: “Uhhh, that’s not red.” Right. We weren’t expecting our pigment to look more like a scab wound than the blood-red color our research promised. But we’re still proud of him! He came so far! He used to be a whole rock!

Interesting contrast of results, right? If you’re like us, I’m sure you’re wondering: what went wrong?

Let’s just say if funds were endless, the Cinnabar sample we ground up would have looked more like this majestic gemstone and less like this unevenly-hued clump of rock. Cheaper versions of Cinnabar appear brownish because they aren’t pure; that explains why medieval artists deferred to its toxic, synthetic relative so often.

Cinnabar, as we later learned, grows in crystalline shapes, so pure cinnabar looks like a gemstone or crystal (pretty!) and is almost translucent. The result of grinding this pure crystal is, of course, the most vibrant, deep red color you could hope for. But cinnabar is vein-filling, which means it grows in between the cracks and onto the surfaces of its surroundings (usually volcanic sites), so cheaper cinnabar will look like a matrix of red weaving over the surface and through the veins of another stone or rock form. If you grind the whole rock/cinnabar formation altogether, the result is a duller, browner red. Our cinnabar sample was certainly not a pure crystal of cinnabar, and that explains why our pigment is on the browner side than the store-bought pigment.

Our cinnabar was purchased from Etsy, and the rough cinnabar samples are much cheaper and easier to find than pure crystals. The cheapest pure crystal we came across in our Etsy browse was listed at $224. To get the good stuff, you have to pay.

If you want to read about some successful pigment experiments, be sure to check out our other classmates’ adventures with medieval paints linked below!

Works Consulted:

Cennini, Cennino. The Craftman’s Handbook: “Il Libro Dell’arte”. Translated by Daniel Thompson, Dover Publications, 1960.

Les Enluminures, TM 644, Cologne Office of the Dead, https://www.textmanuscripts.com/medieval/manuscript-office-of-the-dead-60899

Medlej, Joumana. Inks and Paints of the Middle East: A Handbook of Abbasid Art Technology. Majnouna, 2021. Accessed 20 September 2022.

Ridgley, Vic. “Cinnabar – Epic Mineral Overview.” Mineralexpert.org. https://mineralexpert.org/article/cinnabar-mercury-sulfide-mineral-ore. Accessed 10 November 2022.