Looking at a piece of art can be a stimulating experience in that it can take you to another place in time or lead you to contemplate the present. It may also launch you into an entirely different world or make you think of a concept that you never thought of before. However, visual art itself is timeless in nature, as it does not change; it is independent of any outside person or thing. The effect it may have on the viewer and the viewer’s interpretation is variable as it could change according to the time and space that the viewer is in. This interplay between the viewer’s changing perspective of the piece of art and the art’s fixed nature is what makes the experience of looking at art fun and interesting. This idea can be traced all the way back to the Middle Ages when illuminations were used as an interactive component for the reader of a Book of Hours.

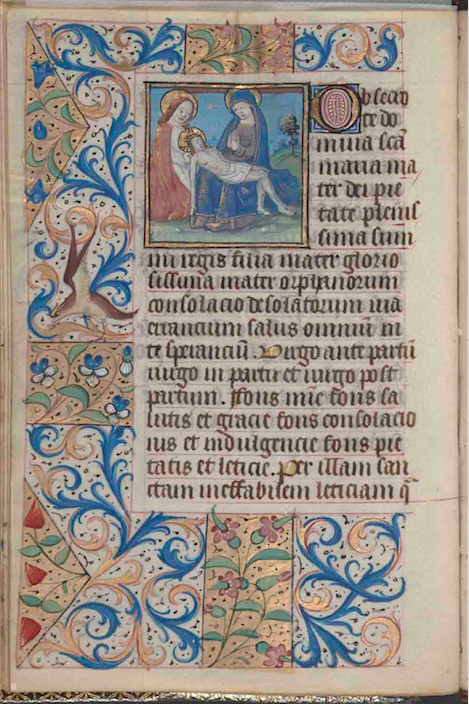

The illuminations would serve as intimate visual links to God or the saint while contemplating the text. In effect, the prayers could now be envisioned while recited simultaneously. In Icon to Narrative: the Rise of the Dramatic Close-up in Fifteenth Century Devotional Painting, Sixten Ringbom brings forth the German term “andachtsbild” which refers to this same concept of a devotional image used for prayer or contemplation. [1] He talks about how these holy figures were usually extracted from their narrative context to create a heightened depiction of the moment in order to evoke an emotional or spiritual response from the reader. By searching images that would be considered “andachtsbild”, I discovered the scene most commonly used is the Pietà, which is the Virgin Mary cradling the body of Jesus after the crucifixion. Conveniently, my chosen prayer book, the Connolly Book of Hours MS 1986.097, has an illumination of the Pietà with Mary and Saint John used to observe along with the Latin Prayers. The Pietà is timeless in that is it not written in the Bible as historical fact; therefore, unbound to liturgical time. It is an event that medieval Christians imagined to appropriately occur after the crucifixion. As a modern Christian viewer, I would say that this is an image that I am definitely familiar with especially around the time of Easter. However, because of the medieval art style and context, I feel detached as I do not look at this daily or devote time to pray with it as one would during the Middle Ages (not saying this applies to every modern Christian but just in my own experience). Using the Pietà in this way allows the medieval Christian to fully experience the act of praying to the Blessed Virgin not only through recitation but also through the eyes. This just goes to show that visual art can stimulate a variety of interpretations and approaches from the viewer despite the art’s fixed nature.

Pietà of Jesus with Mary and St. John

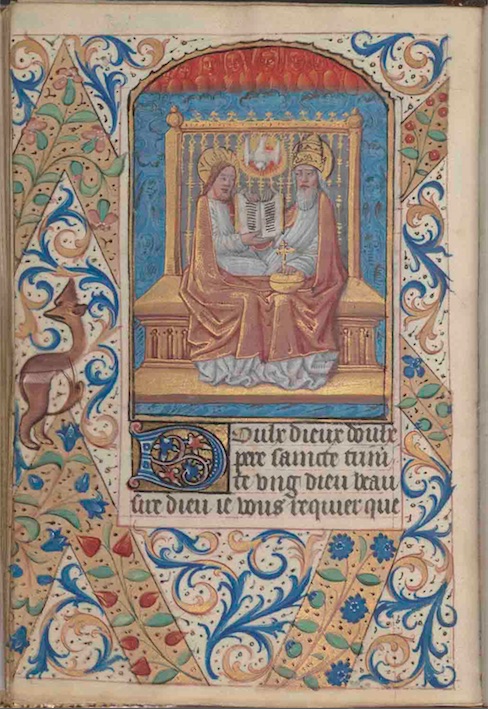

Another example from the Connolly Hours is the large illumination of the Trinity accompanying the Seven Requests to Our Lord from the French Prayers. The prayer is arranged in seven verses, each specifying one request. Something that stood out to me in this illumination is the human depiction of God the Father who sits to the right (from viewer’s perspective) of Jesus the Son. Having been raised in a Christian household, I found this not disrespectful (as some Christians/religious individuals may find) but rare and simply interesting. I had always been taught that God the Father was an incomprehensible Being that could never be imagined in our finite minds, much less depicted as human like ourselves. I began to research the point in which artists (or in this case, illuminators) represented God as a human in art. I found in Medieval Art: A Topical Dictionary, that during the Middle Ages, God was represented as “an elderly man in flowing robes with white hair and a beard” or “may be represented wearing a priestly hat… and he may hold a globe inscribed or topped with a *cross”, which we actually see in this illumination in the Connolly hours. [2]

The Trinity (Seven Requests to Our Lord)

All of this to say, God the Father in the flesh brings him into an earthly light, making him more approachable in the act of praying. It is obviously not bound to a historical moment in time (such as the crucifixion) or narrative, as it is merely created out of imagination – just like the Pietà. The divine and sacred image of God the Father has come down as a man on a throne which is not exactly the prescribed visual that I am used to or had in mind, but I totally get how depicting God as human aids us to get our minds around who he is or what he may be like. For the medieval Christian I’m sure this was super helpful in connecting with God one-on-one, bringing him to a level that was more accessible while praying. In the same way that the Pietà is unbound to time, the fluidity of this image of the Trinity aids the reader in producing serious contemplation and petitioning that stretches beyond the written words.

It is through these lasting and timeless illuminations that the individual can rely on them with consistent prayerful intention while also drawing his or her own interpretations when appropriate. It is remarkable that despite the immobility of these illuminations and visual art in general, they provoke different feelings and experiences in and for us – and I think this is worth acknowledging.

[1] Ringbom, Sexton. Icon to Narrative: the Rise of the Dramatic Close-up in Fifteenth Century Devotional Painting. 2nd ed. Doornspijk: Davaco, 1984, 52-58. Print.

[2] Ross, Leslie. Medieval Art: A Topical Dictionary. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group, 1996, 103-104. Web.