It’s International Literacy Day! And the idea of that day that cuts to the quick of this course’s central problematic: how could medieval laypeople actually read these Books of Hours when they were written in Latin? And what does the (in)accessibility of the language tell us about the linguistic and religious power politics of later medieval Europe? So I’m taking today to muse on a few concepts that we’ll delve into throughout the rest of the semester, and that I will hopefully return to in more nuanced fashion here, down the road.

The UNESCO website states that International Literacy Day’s purpose is, in part, “to promote literacy as an instrument to empower individuals, communities and societies.” Which sounds about right for our understanding of the role that literacy played in later medieval Europe. As society became more oriented toward the written word, especially the written word as a medium for conducting business and record keeping, literacy and power went together in ways that was not true in, say, eighth-century Mercia.

But of course, “literacy” is a complex concept, today as well as in the 1400s. It’s not a binary state, even though it’s often cast that way in elementary school systems and in medieval writings about the litterati, but a spectrum of facilities with the written word. Adults today may be functionally literate (able to keep their accounts) but unable to read for fun, or able to read enough to pass a driving test but not able to read a newspaper. And when we’re operating in a multilingual society (as I’ve had the pleasure of doing, when I was a master’s student at the University of Ottawa), we’re dealing with different levels of abilities within different languages. (I could check out a library book in French, but not write a dissertation in that language.)

Let’s start with a few terms. The OED defines “literacy” as “the ability to read and write” (“literacy,” n.1). Right there, we have to modify our understanding of “literacy” for the medieval world, because reading and writing did not go hand in hand in the Middle Ages. One could be able to read fluently, but not able to write smoothly or at all (writing with a quill pen being a specially taught skill). But even “the ability to read” doesn’t quite cover the medieval understanding of literacy. The Latin term litteratus meant both “able to read Latin” and “cultured, educated” — it refers to an educational status rather than the skill of deciphering letters. So the negative term, illiteratus, doesn’t necessarily mean “illiterate” in our understanding of the word. It just means you weren’t taught to read Latin. Many people could read Middle English, Middle French, or the other vernaculars well without having the same ability in Latin. Now, as Latin remained the language of power through the end of the Middle Ages, even if it was ceding some of that authority to the vernaculars, the problem of illiteracy does remain relevant to the question of the laity’s empowerment or not through these prayerbooks. But it’s not the only way of thinking about literacy in the Middle Ages.

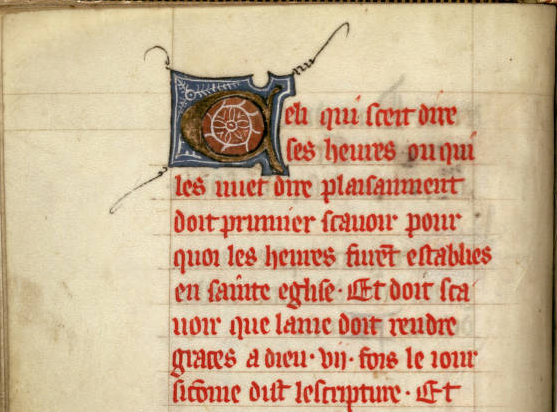

If we change our terms from “literacy” as defined by the OED to “language facility” or “the ability to use a written text,” the questions alter in several ways. First, reading was not necessarily a solitary nor a visual activity in the Middle Ages; much literature was written to be experienced aurally, and I would suggest that Books of Hours were frequently encountered through the ear as well as, or perhaps instead of, the eye. Our best analogy today might be song lyrics or movie lines, texts that are available in printed form but that most of us experience (and sometimes mis-experience) through the ear. Second, one might know what a text says, and have the ability to use it in the appropriate context, without having the facility to read the individual words or with the language more broadly. How many of you were taught in elementary school to sing “Happy Birthday” in Spanish? If you, like me, were taught the song aurally, you know how to make the sounds and what those sounds mean, but I (at least) have no idea where one word ends and another begins. A similar example would be the Latin songs that choirs perform or that we encounter at Christmas. (Do you know what “Gloria in excelsis Deo” actually means?) Third, “the ability to use a written text” involves more than just “reading the words.” It’s the ability to navigate the page or the codex efficiently, to recognize textual divisions and hierarchies by layout signals, and often to interpret visual elements like miniatures or marginal decoration. This kind of navigational literacy is one that I often teach to first-year students encountering academic books for the first time: one cannot navigate an essay collection the same way you’d navigate a novel, even when you can read the words fine.

There’s more to be said about different kinds of literacies, and I have just touched on a few that seem most relevant to the question of how the medieval illitterati used these Latin prayerbooks. Medieval books could deploy quite complex and sophisticated navigational devices, and it does take considerable fluency in those devices to move around a Book of Hours smoothly. Moreover, as is well recognized, the miniatures were also central to the book as a devotional aid, so the ability to “read” the miniatures was an equally critical form of literacy. I also suspect that many who prayed the Hours of the Virgin did so at least partially from memory. A devout person who did use her Book of Hours every day would have had much, perhaps all, of it by heart, and if she had learned to say these prayers at her mother’s knee, she probably learned them by rote aurally as well as visually. I also find it plausible that many laypeople would have known what the Latin services meant (much as I know what “Happy Birthday” in Spanish means) without being able to parse the individual sentences. So even if the Book of Hours’ user could not have translated the words on the page, he or she certainly could have used that written text for the purposes for which it was designed.

But are these textual facilities a form of empowerment? I would say yes, although there are alternate arguments to be made. I would suggest that, when these Latinate, liturgically derived prayers come into the hands of the laity, those readers are able to access some fragment of the priesthood’s cachet. They don’t need a priest to pray for them; they can pray for themselves, in the Church-approved lingo for Talking to God. The Latin words can be used, even if they cannot be grammatically understood. More importantly, as standardized, semi-liturgical texts, these prayers’ and offices’ power lies not in the lexical and syntactical nuances of each phrase, but in the spiritual orientation they organize. When you say the Penitential Psalms, for instance, you know that you are petitioning God for mercy, forgiveness, and succor: those Psalms establish a precise relationship between the pray-er and God, whether or not the pray-er can parse every biblical word. The layperson voicing the Latin words in prayerful supplication does not have the same linguistic access to earthly ecclesiastical power as would an Oxford-trained friar or bishop, schooled in the nuances of rhetoric, disputation, and theology – but he is able to make his voice heard in Mary or Jesus’s ear. And that is a different kind of power than what UNESCO describes, it is still a power we should not undervalue.