We’re lucky at UGA to have a number of medieval bindings in our collections; both the Spanish Gradual and the book of canon law are in their original bindings, complete with metal bosses, blind-stamped leather covers, and a crazy-quilt of pastedowns. But it’s still a treat to call up a manuscript at another archive, open its storage box, and discover that it’s still in a medieval binding.

I’ve had three amazing experiences with medieval bindings so far in England (and I still have a week of research left!), so let me tell you about them.

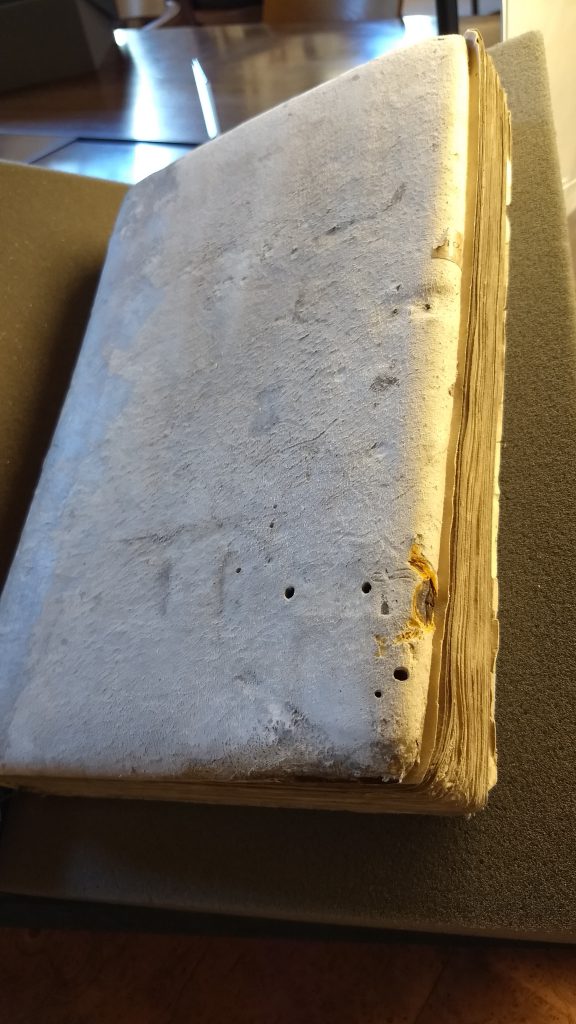

The most recent one was at the Bodleian Library. I called up Bodleian MS 451, a 12th c.. manuscript of sermons and didactic material written by a female scribe at Nunnaminster, the medieval nunnery in Winchester. (That’s right, we know that this particular manuscript was written by a nun because she calls herself a “scriptrix,” which is the feminine form of “scribe.”) It was exciting enough to call up a manuscript from c. 1150 – it’s the oldest codex I’ve had the privilege to handle. But it was nifty to open the box and be confronted with a sueded leather medieval binding; the pastedowns on the inside covers were gone, so I could see the (rather wormy) boards themselves. The Bodleian’s catalogue tells me that this is a 15th c. binding; certainly its edges were flush with its cover (as opposed to inset to protect them, as is true of modern hardbacks), a feature of earlier medieval bindings.

As fun as that manuscript was, it wasn’t the most remarkable binding I’ve handled this trip. Two others were truly jaw-dropping.

The first was British Library, Add. MS 33385. This is an early – mid-thirteenth-century – Book of Hours made for Beatrice, daughter of Henry III. I’ll talk more about this prayer collection in a later post, but it was also remarkable for its cover. (Sorry, no pictures allowed for this one.) The book was in its original wooden boards, albeit rebound at the spine in the eighteenth century. And those boards were not quarter-cut and covered with leather, as is normal: these were carved. Both the front and back covers of this book were made of exposed wood, carved with arches in the form of architectural arcading, like what you’d find in a medieval church. The wood itself was worn smooth, and there appeared to be letters inscribed into the arches themselves. I didn’t have the right tools to decipher those words, sadly. The British Library catalogue suggests that the boards were repurposed for this cover, not designed for it, which may well be. Nevertheless, their reuse as a binding is utterly appropriate: framing the book’s prayerful contents, this wooden, architectural design proclaims the horae as the codicological equivalent to a church. Both are prayerful spaces in which you can petition God in a myriad ways. One you walk into; the other you hold in your hands.

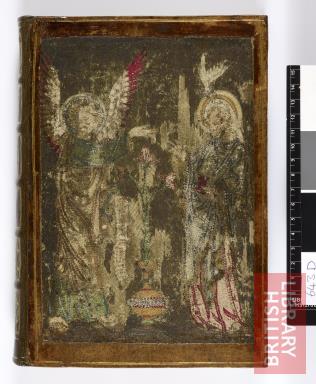

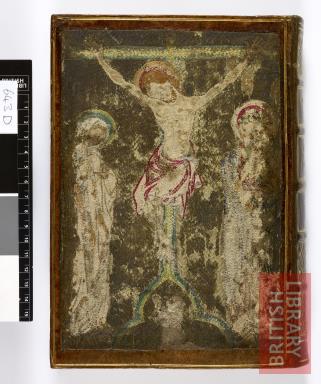

The final manuscript was the most amazing experience I’ve had handling manuscripts, including the experience of calling up the 12th c. Nunnaminster manuscript I discussed above. British Library, Sloane MS 2400 – a fourteenth-century Psalter owned by Anne Felbrigge, a nun of Bruisyard Abbey, has an embroidered cover.

No pictures allowed for this one either, so these photographs come courtesy of the British Library.

As you might imagine, medieval textiles are rare – they don’t have the longevity of stone, parchment, or even wood. But later medieval England was filled with glorious, lush fabrics and tapestries in bright colors and intricate patterns. The English were especially good at a kind of embroidery known as opus anglicanum, or “English work”: dense, figured needlework executed in silk, gold, and silver threads. If you follow the link, which takes you to a Victoria and Albert Museum exhibit from 2017, and look at the pictures, you’ll see that opus anglicanum is like painting with thread: the designs on the liturgical vestments and clothing they show are very like the images we see in medieval manuscripts.

The embroidered cover on the Felbrigge Psalter looked to my untrained eye very much like the needlework in the V&A exhibition. Textile experts who’ve looked at this cover say that it was probably purpose-designed as a book binding; the embroidery technique is different, and more robust. We don’t know whether the panels were executed by a nun or originally made for this manuscript, but it seems possible; nuns did do needlework as a devotional exercise,* and these ones are iconographically appropriate to their contents. Such a cover would have taken weeks, or longer, to embroider, and the stitching itself was possibly undertaken as a spiritual exercise, especially if it was done by a nun. Currently the panels are set into an eighteenth-century cover.

The patterns themselves are suited to a devotional book. The design on the front cover is the Annunciation – the angel Gabriel telling Mary that she would conceive the Son of God, with the Holy Spirit in the form of a dove hovering over her head. On the back is the Crucifixion, with Christ on the cross, flanked by Mary and John the Evangelist, with the manuscript’s owner kneeling at the foot of the cross. These panels are seriously degraded (“conservation” efforts in the eighteenth century didn’t help things); the flesh-toned thread is entirely worn away and the blues have faded, so it’s impossible to see expressions on faces or even make out the gender of the owner praying below the cross. But the red and pink silk is still bright, and the greens kept their tones, giving a hint of these panels’ earlier lush beauty.

Like the carved wooden cover of Princess Beatrice’s book of hours, the embroidered cover for the Felbrigge psalter proclaims its contents: this is a book for praising God. It is also a textile that performs a bit of textual interpretation. The contents of the book are primarily the Psalms, but the cover encloses those Old Testament songs of worship with the two defining events of the New Testament, the Incarnation and the Crucifixion. Just as the Psalms were reframed, through other texts like hymns and antiphons, in the Hours of the Virgin or the Hours of the Passion to give them Marian or Passion significance, so does this Psalter frame its contents with the Annunciation and Crucifixion. Whether they were singing them in their daily round of services or pouring over them in personal devotion, the nuns would have read their Psalter through the lens of New Testament events, seeing the connections across these two periods in salvation history.

The Felbrigge embroidered binding is therefore not just a pretty cover or a devotional aid; it’s an act of prayer, a gloss on the book’s contents, and a typological figuration of the psalms’ ultimate significance.

Postscript

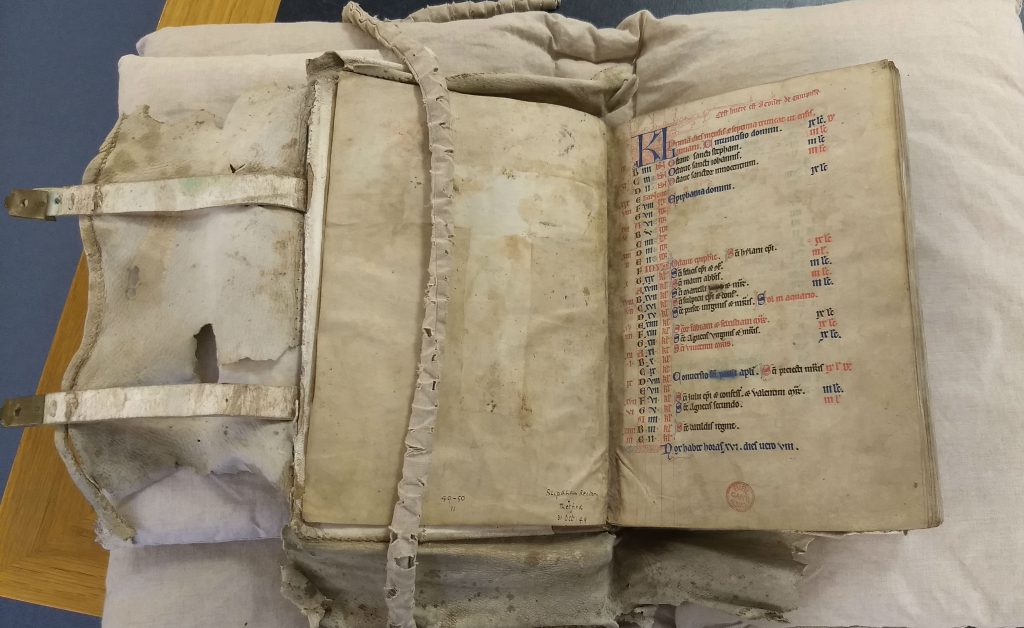

So I post this post, thinking I had already hit the binding jackpot for the trip. But then, just two days later, I get to view this beauty at Cambridge:

It’s a wrap-around binding in white doeskin (maybe? At least a soft, supple leather, very like kid gloves). The cover wrapped all the way around the fore-edge, and the metal clasps — attached to the two stiff leather bands — were still intact. You can see the flaps of leather that protect the top and bottom edges of the pages, much as a chemise binding would do. It was downright frightening, getting this book in and out of its archival box!

Notes

*For example, the female hermit Christina of Markyate embroidered a pair of shoes (if my memory serves – I am on a different continent from my text!) for her patron, the abbot of St Albans; they may have been similar to Archbishop Walter’s shoes, featured on the V&A online exhibit. Christina would have been sewing the abbot’s shoes about 40-50 years before Walter’s shoes were made.

Bibliography and Further Reading:

“The Felbrigge Psalter,” Textile Research Center, Leiden. https://trc-leiden.nl/trc-needles/individual-textiles-and-textile-types/book-covers-and-book-cushions/felbrigge-psalter

The Life of Christina of Markyate, trans. C.H. Talbot, Samuel Fanous, Henrietta Leyser (Oxford: World Classics, 2009).

Penelope Wallis, “Embroidered Binding of the Felbrigge Psalter,” British Library Journal 13 (1987): 71-78.

P. R. Robinson, “A Twelfth-Century Scriptrix from Nunnaminster,” Of the making of books: medieval manuscripts, their scribes and readers. Essays presented to M. B. Parkes, ed. P. R. Robinson and Rivkah Zim (Aldershot: Scholar Press 1997).