[Note: In October, I gave a presentation on the work of this course — a sort of apologia for the course as well as a call to arms for more hands-on research courses in humanities classrooms — at the semiannual UGA Symposium on the Book, with the theme of “Textual Afterlives.” What follows is a version of that paper, edited for this context.]

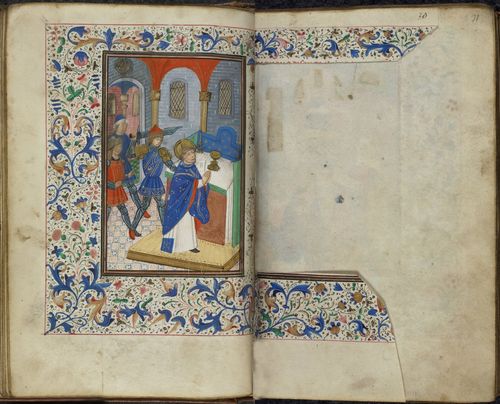

When we think about the afterlives of medieval manuscripts, we often focus only on one aspect of that afterlife: their journeys from medieval users to modern libraries. In these stories, manuscripts have quite an adventurous time. They may be defaced and abused for political reasons, as in this prayer to St. Thomas Becket cut completely out of British Library, MS Harley 2985.

They may be deliberately broken and recirculated for quasi-altruistic reasons, as we learned about from Dr. Scott Gwara of the University of South Carolina, who spoke at the Symposium on the Book about Otto Ege‘s book collecting – and parting-out – activities. Or they may be threatened and damaged by fire, as when Ashburnham House caught fire in 1731 and damaged or destroyed several ancient manuscripts in Sir Robert Cotton’s collection.

A manuscript’s adventures are greatest outside the library, where it can be buffeted about by the whims of fate and the antics of private collectors.

Once the manuscript has reached the safety of the archival vault and reading room, however, we often presume that its active life has ended. It sits in quiet retirement, rarely consulted but by white-bearded, white-gloved scholars. Or, if we do imagine ancient materials to have an afterlife in the archives, that afterlife is as exciting and adventure-filled as its pre-archival experiences.

Like this:

Or this:

I’d like to rethink this boring picture of the contemporary afterlives of medieval manuscripts, in ways that are especially relevant for those of us teaching within smaller institutional repositories. While the manuscripts held within large collections of ancient materials (like those at Stanford or my alma mater, Cornell) do have active social lives, those in libraries without substantial medieval or early modern holdings often get ignored. There is no critical mass for their study, display, or engagement. These items may not be perceived as having intrinsic scholarly or aesthetic value: they are often unprovenanceable single leaves in highly abbreviated Latin texts, sporting no exciting decoration. Their worth is not immediately apparent.

I would like to suggest, however, that we can give these mundane manuscripts new lives when we use them in the undergraduate classroom. And by “use” I do not mean the brief “oooh, shiny!” visit to the rare books room once in a semester. Rather, by “use” I mean that we help students grapple with these books and leaves intimately, struggling with their physical makeup, their script, their decoration, and their deterioration.

So what follows is an overview of, and teaching manifesto for, the Hargrett Hours Project.

What is novel, even radical, about this series of courses is my conviction that undergraduates are capable of doing original, authentic research into the Hargrett Hours and the other medieval items held by the Special Collections Library. This research is neither an exercise nor a way to test mastery of the material. Rather, the students perform their mastery through original research. Because these items have never been studied, anything the students discover about them constitutes a true contribution to knowledge. And even though their discoveries may seem inconsequential on their own, such “small data” becomes meaningful when placed into the right context. Additionally, a course-based major research project like this one provides a new way of thinking about what humanities research looks like and how we professors engage with undergraduate scholars.

So let me walk you through three reasons why this kind of pedagogical project matters.

1. Hands-On Learning

This kind of course allows students not simply to learn exciting things about medieval manuscripts, but to apply what they have learned to an ancient, “live” (as it were) item. Here at UGA, we are all deeply familiar with the new Experiential Learning initiative; as a result, there is much research that explicates why hands-on learning is valuable.

However, I’m not going to throw statistics or case studies at you. I’m going to go one better. I’m going to give you what one student wrote after completing the fragment practicum exercise, which we did early this semester:

In summary, I left this week’s final class meeting with two main takeaways. First, despite any amount of studying and reading, the most effective way to learn is to be stretched and learn is to apply the information. The information that we learned before last week’s mini-exam was essential to examining manuscripts in class today. However, leading to my second takeaway, a thorough knowledge of the readings and images covered was not alone enough to complete the practicum well. Much against the way students are often expected to think in school, you can’t simply study well to perform well in this type of exercise. There is no magic formula, and (much against the way I like to think) there is often not a single correct answer to the questions that we must ask of the manuscripts. Collaboration, creativity, and patience are essential in this process. You must be willing to start over and look at things from a new perspective. [italics original]

I simply cannot put it any better than that. It takes flexibility, ingenuity, and patience to apply the raw facts that we learn in the classroom, and only in applying that information can knowledge be actualized.

2. A new kind of undergraduate humanities research

This kind of course also allows students to participate meaningfully and collaboratively in an ongoing research project. I would compare the work we are doing in these courses to the efforts undertaken in a research lab, albeit in the space of the classroom and archive instead of the field and laboratory.

The University of Georgia likes to praise its commitment to undergraduate research, and I do believe that programs like the Honors College and CURO do a laudable job of supporting budding scholars. However, it is also true that these programs are skewed toward a particular subset of our undergraduates. Only students who have met the Honors Program requirements early in their undergraduate careers can participate in those opportunities. And these research options are more readily available for students interested in the sciences, where there is greater capacity for integrating an undergraduate into a research project, due to the collaborative and long-running nature of most labs.[1] Yes, we do have humanities undergraduate research at UGA, but it can be more challenging for students to discover, because it is less communal, more invisible.

Let me illustrate my point. The CURO homepage hosts an extensive carousel of images of students undertaking research in a variety of settings. The majority of the images are like this one:

We see students in a lab or at a field site, often manipulating implements, often shown in a group, often with a professor in train. As a picture, it screams “hands-on collaborative learning.”

Several images in the carousel also represent humanities research, but most of them look like this:

Here we see a solo student, surrounded by books. In other pictures, the student is depicted looking at the books rather than at the camera, further isolating her from both the viewer and her environment. Never is an attending professor shown, nor do we see this humanities researcher interacting with her peers.

Now, this image does not misrepresent undergraduate humanities research. If you students have ever taken a directed reading (and I’ve overseen a few), you’ll know that this picture is accurate. You typically work alone, meeting occasionally with your directing professor. If you’re lucky, your roommate will look on you benignly when you rabbit on about the amazing discovery you made in the library, but you do not have a cohort who really knows what you’re talking about. Such images of humanities research remind us that this one-on-one dynamic can be isolating: there is no place to share your successes or frustrations with those who truly understand.

Just because this image is accurate, however, does not mean that it is the only model of humanities research available.

English, history, philosophy, languages: we don’t have labs. We have conferences and talks; if we are fortunate (and persistent), we have multi-year funded research projects; we have coffee shops and wine hours and chance meetings in libraries. We have spaces to share our work, but we have few spaces to collaborate on our work.

One of those spaces is the classroom.

The classroom is the single guaranteed space in the humanities where, for the space of a semester, we can collaborate on common intellectual pursuits. It is the one place where, for a few hours a week, we are surrounded by people who have read the same books and are asking the same – or perhaps incredibly different – questions about them. It is the one space where professors and students can generate knowledge collectively. It is therefore the best place to undertake a shared research endeavor.

By moving intensive undergraduate research from the extracurricular realm of the lab or the directed reading to the space of the classroom, we can achieve several positive outcomes. We move the research experience out of the hands of the intellectually elite (the Honors students, the students who have the leisure time to engage in extended projects) into the grasp of the intellectually curious (those brave enough to dedicate their time and energies to the course). We move the humanities research experience from the one-on-one dynamic of the directed reading into the interactive environment of the semester-long course. We craft an arena in which the lines differentiating the professor (as the disseminator of knowledge) and the student (as the consumer of knowledge) are blurred, even erased. Finally, by turning the classroom and library into a kind of humanities lab, we give our students the experiences of applied research, shared endeavor, and hands-on learning that are, frankly, not always easy to come by in Park Hall.[2]

And by engaging students in this kind of hands-on, collective project, we give them skills that move. No, none of my students will need to decipher letter batârde again, but they are gaining skills they will use for the rest of their lives. How to think laterally. How to perform tedious tasks. How to work collegially. How to turn a dead end into a new research question. How to write a report. How to think about audience.

Most importantly, the students’ focus moves from product (how to get an A in the course) to process (how to solve the puzzle). And isn’t that the purpose of education, at any level?

3. Manuscripts revivified

These books and leaves are no longer sitting in their folders in the vault beneath the reading room, marking time until the zombie apocalypse. They are in constant use throughout the semester – a use that can have a detrimental effect on their longevity if we’re not careful, true, but it’s a use they were meant for. None of the manuscripts or leaves in our collection were designed to be collector’s items; we own nothing that de luxe. Rather, they were made to be read, consulted, prayed from, sung from. And while we may not be returning them to their original uses, we are indeed using them with the kind of intense focus their medieval owners would have recognized.

So I’d like to end on a passage, again written by a student after the fragment practicum:

One of the byproducts of manuscript study is that it allows manuscripts to continue to “live” as they are read. Old books – especially very old texts like manuscripts – become, too often, artifacts or art objects. People collect old books because they look cool and interesting, and there’s a long history of pulling apart medieval manuscripts so that pages may be displayed as art. … What happens, though, is that the purpose of the text is subsumed by its material aesthetics – a book which is no longer a book in purpose, just in form. …

The work we’ve done in class this week, as well as the work done by generations of academics, returns the manuscripts to their purpose. They are being read and read deeply; because of issues of language and script, we cannot simply skim them and toss them aside. We look at them slowly and attempt (some (OK, me) with more success than others) to reproduce their words not to simply create a copy but to understand what we are seeing. It’s neither simple nor fast, but an act which allows us to not simply reproduce what others have done but to produce a new reading moment with texts hundreds of years old. Our transcriptions may be reproductions, but our readings and reading-experiences are new; in this sense, all manuscripts are palimpsests of readers. As we describe our manuscripts[,] we are engaging with our pages in ways that goes beyond the usual practice of reading and only happens because we are working with texts older than the United States.

And that is the very best afterlife that we can offer these ancient books.

[1] One notable exception is the Linguistic Atlas Project, housed within the English Department and Linguistics Program at UGA; many English majors have done stellar research within this program.

[2] Since I originally wrote these words, our course lists for Spring 2017 ENGL courses were posted. Among the intriguing classes being offered, I note two that do provide the kinds of active learning I describe here: Dr Barbara McCaskill’s ENGL 4810, “Literary Magazine Editing and Publishing,” in which students work with UGA Press on issues of publication; and Dr Fran Teague’s ENGL 4890, a course on archival research and dramaturgy, which has been introducing students to authentic archival research for ages. Keep ’em coming, people.