Have you ever wondered how artists decide what to depict in their paintings? A simple answer would be “they draw whatever they like/are able to draw,” and this would be true for a limited number of cases. A more complex and more accurate answer requires an in-depth study of images and symbols that help to identify people depicted in the works of art – the main task of iconography. Depicting religious subjects, artists wanted to make their figures recognizable to the reader, so they drew from a standard repetoire of visual features to give clues to which saint was which. We might not pick up on these clues as fast as medieval people, but with some studying we can still figure them out. It should also be noted that the smaller the image, the more difficult it is to make it speak clearly.

With all of this in mind, let me give you an example of the story that one little picture from a 15th century manuscript can tell you.

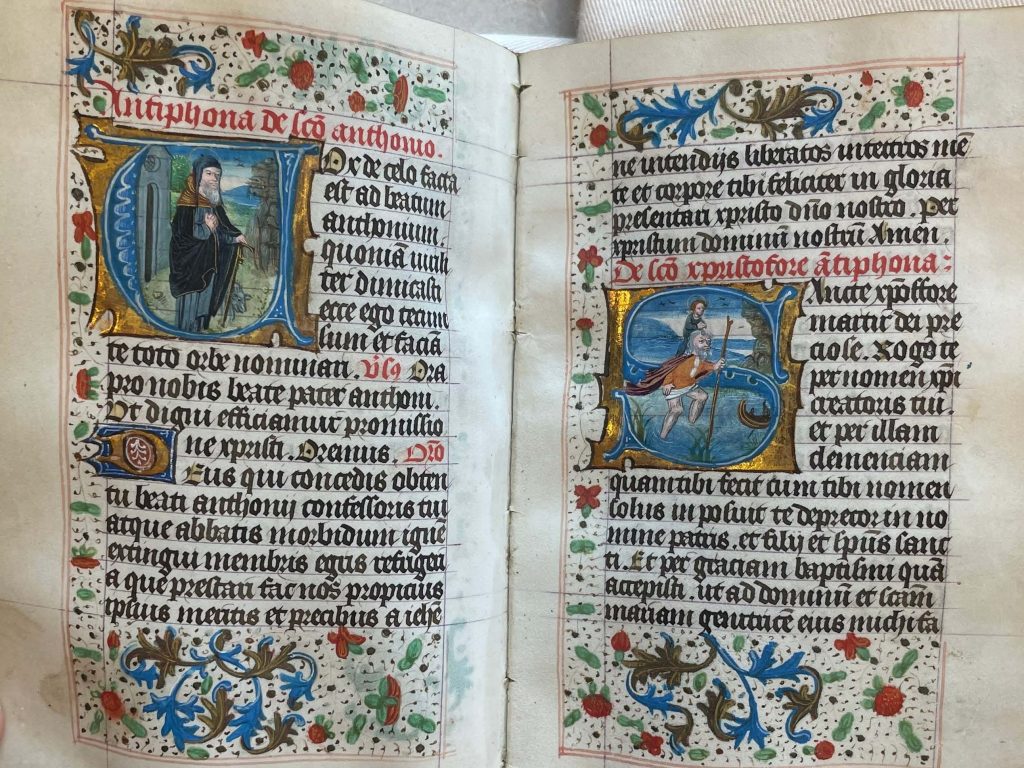

Take a look at this opening and think about what you noticed first. Probably, two pictures with text around them and decorations at the top and the bottom. Closer inspection would reveal an old man standing in the image on the left and an old man carrying a child and walking in water on the right. Who are they and why are they depicted in this way? These are the questions a curious mind would conjure up. If you wonder what the answers are, you are in for a little scholarly treat.

To begin with, this opening belongs to the Suffrages section which contains a set of saints, interceding with God on behalf of people seeking help (you can read a short overview here). The page on the left includes a historiated initial (a capital letter with a figure/scene) of St. Anthony, brief information about him and a prayer sequence. The suffrage on the right is dedicated to St. Christopher and sorting out his iconography would need its own blog post.

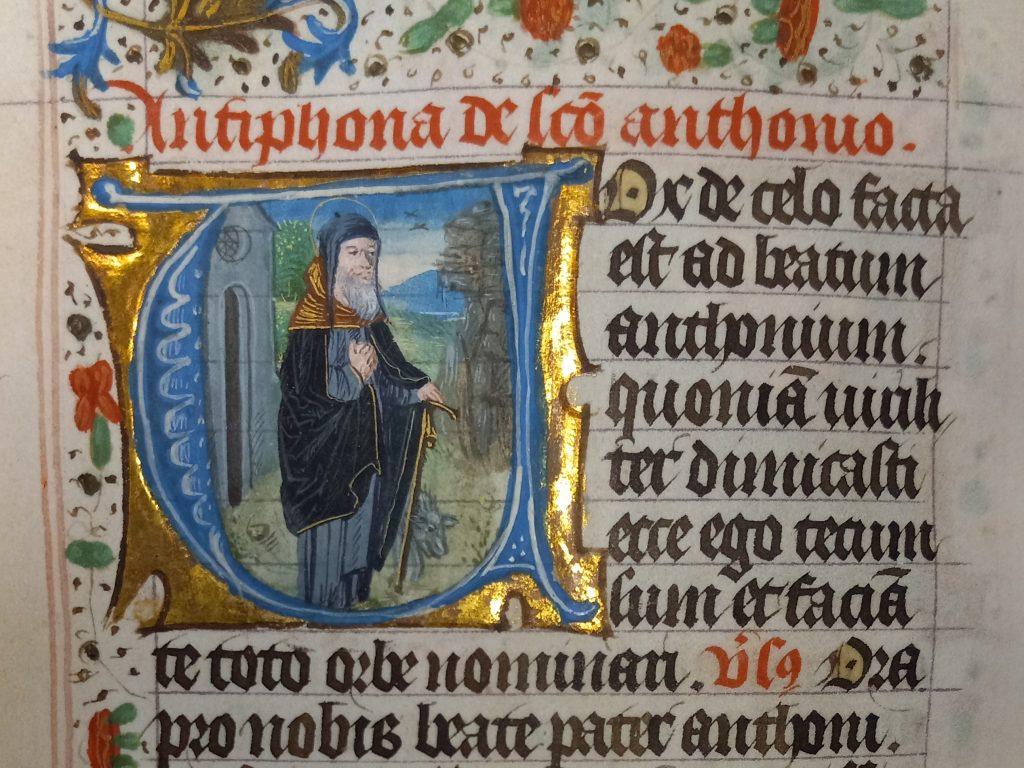

Further examination of St. Anthony’s depiction requires a closer look at the image below.

A shiny border surrounding a letter “A” in blue and white ink frames this 7-line-high image of the saint. A thin golden halo above Anthony’s head shows that the man has already gained his holiness. Modest gray clothes signal that he is a monk; a black cloak with golden lining and a hood indicate that the man is an abbot (the one in charge of other monks). So, by using specific kinds of clothes the artist managed to convey some valuable information about the status and rank of the person in the picture. We’re able to identify him as an abbot, and we know which abbot he is – St. Anthony – from the rubric above the initial that names him as “Anthonio.”

Known as a hermit who spent most of his life in the desert, he became the forefather of asceticism (the practice of abstaining from physical/psychological desires to attain a spiritual ideal). We are obliged to Athanasius, an Egyptian theologian who provided the first, fourth-century narrative of the life of St. Anthony and his teachings, for spreading the ideals of living in humility and prayer. Translated into Latin, these stories popularized the ascetic lifestyle in the East and the West and helped strengthen Christian orthodoxy. Most significant and memorable were the stories about temptations the hermit resisted and the miraculous healings he performed through prayer. They took root in the consciousness of people and soon became a solid foundation for his image and beliefs associated with him.

From the 4th century and onward, St. Anthony had been considered a mediator between mankind and the Almighty. So, when his relics were unearthed in the 6th century and around 12th century housed in a chapel in Arles, this abbey became a major attraction for pilgrims and the sufferers. The arrival of the relics coincided with the peak of a mysterious disease that affected many Europeans: “sacred fire.” Although this ailment tormented Europeans from the 6th through late 19th century (documents testify to at least 130 epidemics), the true culprit – ergot – was identified only in the 17th century. Favoring the rainy season, this fungus contaminated crops, mainly rye (a staple food in many European regions), and, ending up in the flour, caused ergotism. Toxic alkaloids contained in ergot affected the central nervous system and caused blood vessels to constrict, which led to necrosis in peripheral body parts (hence the fire in the name of this disease).

However, the belief in the healing powers of Anthony’s relics was strong, so the sick would come seeking help at his tomb, overseen by the newly formed Order of the Antonites. The Antonite brothers took care of the sufferers who complained about burning pain in their limbs and hallucinations, which were interpreted as demonic possession. As people might have connected the symptoms with stories about the saint’s battles with demons, the disease was soon known as “St. Anthony’s fire.” This link was solidified in iconography, where the saint was depicted standing in the ring of fire, like in the miniature below.

If you scroll up and look closely at our historiated initial (as well as this miniature), you’ll notice a beast, peeping out from behind St. Anthony’s cloak. Not all illuminators were good at making it recognizable but let me assure you that it is a pig. This unusual attribute appeared beside the hermit during the Middle Ages specifically because of those people who came to the Antonites’ chapel. The brothers not only tended to the sufferers, but also provided them with food. Raising pigs (and any other type of domesticated animal) was at that time prohibited in residential areas, but the Antonites became an exception. How can one forbid breeding pigs to feed the sick at the abbey? The privileged swine, though, were specifically marked: their ears were cut and they wore bells around their necks, like in the miniature below.

It should be noted that the staff St. Anthony holds in his hand in both of these miniatures is called crozier. Hook-shaped (like a shepherd’s staff), in an abbot’s hand it becomes a symbol of office. However, many images of this saint show him leaning on a tau-shaped crutch. Although crosses shaped like the Greek letter tau had a variety of meanings, by the later Middle Ages the tau cross became primarily associated with St. Anthony, symbolizing his abbatial authority and referring to his extreme longevity. In addition to this, the tau cross was ascribed protective powers and the ability to make the disease leave the wearer alone.

Apart from depicting a T-shaped crutch (like in our initial), the artist makes an unusual decision to draw bells attached to the pigs’ ears. Sometimes St. Anthony would also hold the bell in his hand. The function of the bell was to “announce” the presence of the swine, so that pedestrians were aware of the animals around and accidents could be prevented. But in the hand of the saint, it can also stand for “order.”

The association between the saint and fire, pigs, and bells not only was a logical outcome of a mere coincidence, but also became a determinant factor in shaping St. Anthony’s image. Now, looking at the Suffrages in BOH 159, we can see how the color and style of clothes as well as a swine-like beast help to distinguish St. Anthony from other saints. The lack of all the “traditional” attributes can be justified by the size of the image and, perhaps, the preferences of the artist. For example, a mere four-line space didn’t stop the decorator from setting this St. Anthony on fire.

But in BOH 159 the artist depicted a solemn figure of the abbot and a pig, modestly peering out from behind the cloak, against a landscape in a cool color palette. The tranquility that emanates from this image should have extinguished worries in the owner’s soul and helped establish the connection with St. Anthony through prayer in the times of need.

Featured image: foliated border with acanthus (BOH 159, f. 68 v.)

Works Consulted

Athanasius. The Life of Antony. Trans. Tim Vivian. Cistercian Publications, 2003.

Cherry, John. “Healing through faith: the continuation of medieval attitudes to jewellery into the Renaissance.” Renaissance Studies, vol.15, no.2, 2001, pp. 154–171.

Grzybowski, Andrzej, et al. “Ergotism and Saint Anthony’s Fire.” Clinics in Dermatology, vol. 39, no. 6, Nov. 2021, pp. 1088–94.

Husband, Timothy B. “The Winteringham Tau Cross and Ignis Sacer.” Metropolitan Museum Journal, vol. 27, 1992, pp. 19–35.

Fenelli, Laura. “Pigs in medieval cities: Saint Anthony’s unusual attribute.” Animaltown: Beasts in Medieval Urban Space. Eds. Alice Choyke and Gerhard Jaritz. British Archaeological Reports, International Series; 2858. Oxford: BAR, 2017. 52-58.

Foscati, Alessandra. “St Anthony the Abbot, Thaumaturge of the Burning Disease, and the Order of the Hospital Brothers of St Anthony.” Saint Anthony’s Fire from Antiquity to the Eighteenth Century, Amsterdam University Press, 2019, pp. 125–184.

Wight, C. Glossary for the British Library Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts, The British Library, 25 Aug. 2005, https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/glossary.asp.

Les Enluminures, BOH 159, Book of Hours (Use of Rome?)

New York, The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.19, Book of Hours

New York, The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.76, Book of Hours

New York, The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.83, Book of Hours

Walters Art Museum, BOH W.170, Book of Hours