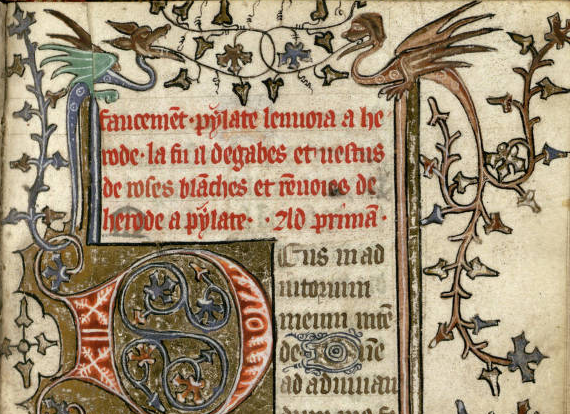

I’m excited about the Houston Book of Hours (University of Houston, Special Collections Library, BX2080.A2 1400z, Use of Reims). It’s a fun sample: easy to decipher script, helpfully placed navigational rubrics, plenty of vernacular, and nicely standard texts. It’s one of the less densely decorated manuscripts I’m offering the students this unit – there are no miniatures in it — but the illuminations it does boast are impressive, heavy with gold leaf and swarming with marginal dragons. It would definitely have been a manuscript to be proud of, but doesn’t rise to the same de luxe level as the Hours of Catherine of Cleves.

I’m also excited to use a manuscript from a repository not known for its medieval holdings (like us!), and interested to see how they are presenting a full codex online. It’s not the most graceful interface, sadly – your browser has to load each folio individually, you can’t view a full opening, and you can’t easily navigate from one folio to a distant one without a lot of scrolling. Still, the scroll bar of thumbnails is helpful, and the scans themselves are crisp and typically load smoothly.

There are two truly thrilling things about this Book of Hours. First is the use of the French vernacular: all the rubrics and some of the prayers (including the Hours of the Passion) are in French. While it was not uncommon for fifteenth-century French Books of Hours to use French language rubrics,[1] it’s still great to see it in action. It’s even more fulfilling when you tend to work with English Books of Hours (as I have), which include very little vernacular. Many of these rubrics are extensive, seeming to give directions on how to use the book and advice on how to best orient oneself spiritually while praying from it. I haven’t taken the time yet to transcribe and translate these rubrics, so I wonder about the level of detail they may contain.

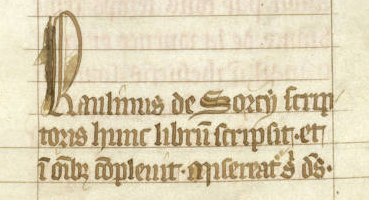

The other remarkable element falls at the bottom of fol. 15r:

The colophon names the scribe, Paulinus de Sorcy, and claims that he wrote and finished the whole thing. I have no idea who Paulinus was, where or when he lived, or how many other books (and of what sorts) he wrote – it’s just fun (and not usual) to have the scribe’s name.

Apart from these “shiny” elements, though, the Houston Book of Hours invites a variety of questions. What is the origin of the directional rubrics interleaved within the Hours of the Virgin? Was Paulinus copying these from a stock source that I’m just not familiar with? Or was he crafting these directions himself? The rubrics frequently fit neatly into the available space – they fill up the bottoms of fols. 44r and 56r, following Prime and Nones (respectively), allowing Terce and Compline to begin at the top of the following folio – that one might speculate that Paulinus wrote, or at least edited, them to fit the page. In which case, Paulinus would be playing the role of spiritual advisor and scribe simultaneously.

Another question is, of course, the identity of the first owner. In the top margin of fol. 27r, Lauds of the Virgin, is portrayed a young woman, wearing a simple pink dress. There are other human figures in the manuscript’s decorated margins, but they are typically musicians or hybrid creatures. This woman is atypically normal. She’s also wearing her blond hair uncovered, except for a small green circlet. Might this be an owner portrait of an adolescent girl? That hypothesis is a stretch, I grant; I would expect such an owner image to appear at the beginning of Matins (as in, for example, the Hours of Catherine of Cleves). Nevertheless, I am reluctant to completely reject that possibility, in part because so many prayers included later in the manuscript are heavily focused on family and parents. One prayer on fol. 128r has the rubric “oratio pour ses amis,” two more rubrics on fol. 171v read “pour pere & mere” and “pour ses bienfaiteurs [benefactors],” and I suspect I’m missing more. Were this designed for a younger woman, still a few years away from a marriage and family of her own, it might also account for the extensive directional rubrics, perhaps thought needful for a less mature user. This is crass speculation, I fully admit, but it’s speculation that the book itself encourages.

This manuscript really cries out for extended attention, and I hope at least one of my students – or someone outside my classroom – will give it the love and affection it deserves.

[1] Virginia Reinburg, French Books of Hours: Making an Archive of Prayer, c. 1500-1600 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), esp. 96-100. She notes that “[m]anuscripts produced after the middle of the fifteenth century usually included at least a few French texts” (96), but this one contains much French, including the Hours of the Cross — an anomaly according to Reinburg’s research. The illuminations, however, look early fifteenth-century to my novice eye; suggesting that its use of vernacular may be something special. Experts, weigh in!