Baltimore, Walters Museum, MS W.197 is a wonderful little Book of Hours for students to cut their manuscript teeth on. The contents are fairly straightforward, with a few well-marked curve balls (discussed below); the script is clear and easy to read, using only simple abbreviations; and the illuminations are beautiful. The finding aid explains that the miniatures were executed or influenced by the Flemish artist Willem Vrelant. Not being an art historian, I had to look him up; the Getty tells me that he was one of the most prolific illuminators in mid-fifteenth-century Bruges, a time when Bruges and the Low Countries were at the forefront of Continental book production. Given the prolific output of Vrelant and his assistants (or imitators), we can place the Walters manuscript at the turning point between bespoke and mass-produced Books of Hours: although the manuscript itself is clearly tailored to its original owner’s devotional preferences, it’s also the product of artisans who make their living off this kind of commission.

The manuscript has more than art historical value, however. I am particularly intrigued by the selection of saints and their visual presentation in the manuscript. For instance, St Adrian of Nicomedia – not George or Michael the Archangel – appears as the military saint of choice in the sufferages.

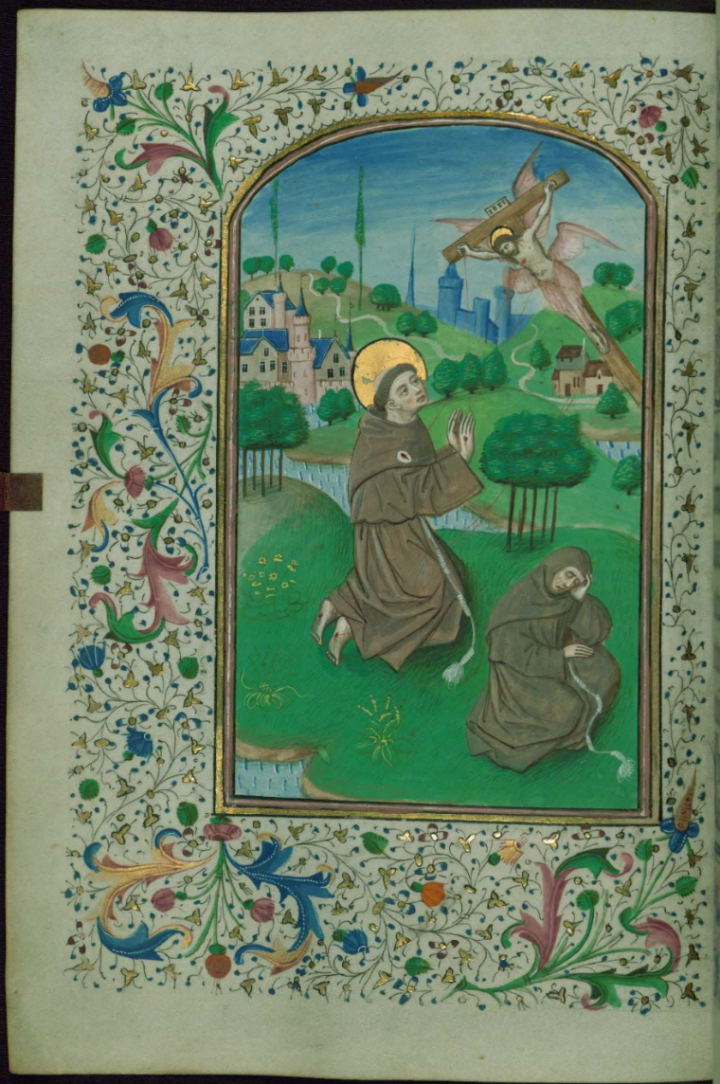

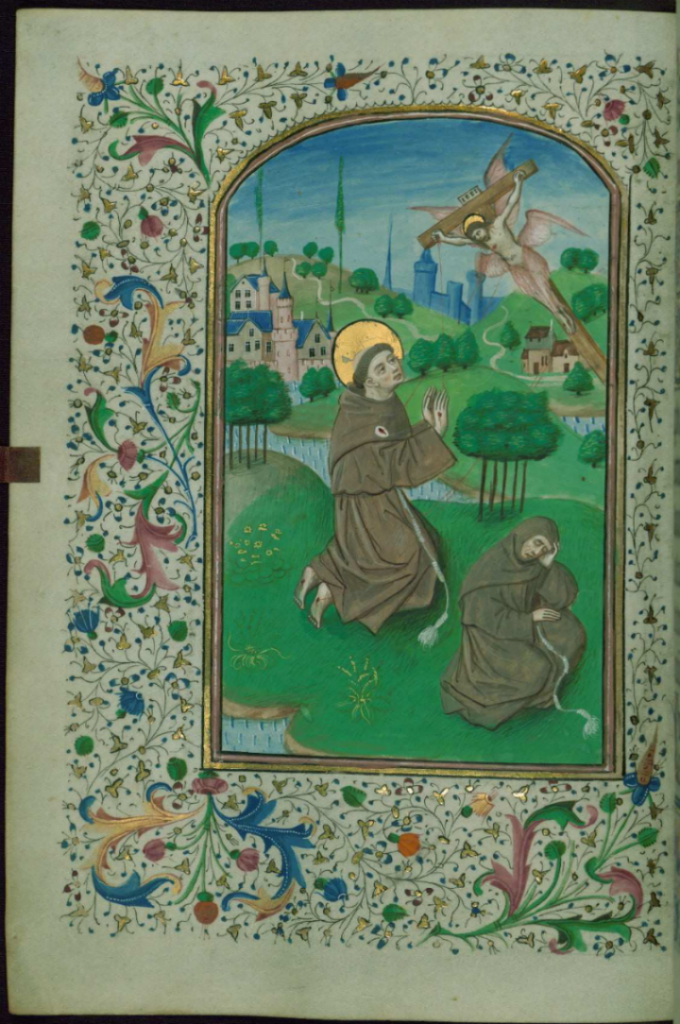

Adrian was an early Christian martyr whose relics were held at the Abbey of Geraardsbergen, south of Ghent, and who was widely honored across the fifteenth-century Low Countries. [1] Also of possible interest is the miniature and suffrage of St Francis of Assisi, shown with his stigmata (pictured at the top of the post). Although Francis was of course widely venerated by the mid-fifteenth century, I wonder how frequently he merits a suffrage plus miniature. He does appear in Walters W.197’s calendar and litany (and another Franciscan saint, the tertiary Ivo of Kermartin, also shows up in the calendar), while the burial scene in the miniature for the Office of the Dead (fol. 175v) clearly occurs within a monastic cloister. What would constitute a distinctively Franciscan influence on the manuscript’s composition? [2]

Also of interest – and something that students should be aware of – is the manuscript’s liturgical ambition. It includes a Mass for the Virgin Mary (fols. 62v-56r) and the Hours of the Virgin is followed by directions for modifying the Hours for Advent (fols. 135v-145v). This is more complex liturgifying than we’ve seen in our other sample horae, inviting questions about what kind of user would have requested such sophistication. These elements suggest that a confessor or spiritual adviser – a friar, perhaps? – may have had a hand in the manuscript’s composition.

The Walters presents its digitized manuscripts to the public in a variety of formats, some via browser-based page-turning interfaces, and some as a continuous PDF document. Walters W.197 is one of the latter. Although this comparatively low-tech interface has its downsides, it is also convenient to download the PDF to your hard drive, freeing yourself from the vagaries of internet access. These days, PDF is the digital equivalent of medieval girdle-bound books: it’s easy to carry with you — and access — wherever you go.

[1] Harry Schnitker, “Margaret of York on Pilgrimage: The Exercise of Devotion and the Religious Traditions of the House of York,” in Reputation and Representation in Fifteenth Century Europe, ed. Douglas Biggs, Sharon Michalove, and Albert Compton Reeves (Leiden: Brill, 2004), 81-122, at 112-114.

[2] The only article on Franciscan Books of Hours the I was able to uncover quickly was Paula Hutton, “Franciscan Books of Hours from Italy in the Newberry Library,” Essays in Medieval Studies 4 (1997), 143-150 (online at http://www.illinoismedieval.org/ems/VOL4/hutton.html), but her discussion of these Italian examples wasn’t terribly illuminating for this Flemish manuscript. As always, research recommendations welcome!