Books of hours clearly begin to illuminate the spiritual and religious lives of their medieval Christian owners, but I am far more concerned with what these texts say about the medieval Christian’s understanding of time. Gazing back across several centuries and the several computer screens that make such manuscripts visible to me has brought the Office of the Dead and the Hours of the Virgin to the forefront of my considerations. Based on my limited knowledge of their typical placement and usage in a book of hours, I’ve come to think of them as structural supports in a comprehension of time that collapses the temporal and eternal along purely religious lines.

As one of the central texts in any given book of hours, the Hours of the Virgin constructs what Reinburg would likely call “the artificial day,” an eight part sequence of prayers and miniatures that imposes religiosity on the day to day experience of temporality [1]. Perhaps artificial is an inadequate word, though. The hourly, daily, and weekly routine of reciting the Hours was the exclusive reality of the church and, by extension, the exclusive reality of lay people who placed their private devotions within an identical structure. Secular temporality was overtaken by a religious one that promised a dual progression across temporalities. On the one hand the pray-er would join Mary in the distant quasi-biblical scenes of the miniatures, and on the other hand he or she would continue through their own current and livable temporality. The pray-er might begin their day with meditations on an image of The Annunciation (accompanying Matins, the first hour), and as Mary was invoked as mother, intercessor, and receiver of angels, she was also beckoned to step into the pray-er’s reality and accompany them through eight carefully set stages.

Mary’s existence in Heaven and her theoretical existence in the hands and hearts of the pray-er would only serve to suggest that the eternal, a time and dimension outside of time, beats either above or below the temporal experience, but we’ll get to that later. Basically, if the hands of a pocket watch will turn ever forward, so would the pages of the Hours of the Virgin, bearing the medieval Christian into a reality pressed with a multiplicitous (and religious) time.

The Office of the Dead is yet another central text in a common book of hours and while it does speak to a medieval preoccupation with death itself, it also indicates a concern with Purgatory, that initial shore of eternity. It was impossible to actively experience Purgatory and because even the most official of reports estimated the time one would spend there to be “potentially thousands of years,” a new understanding of time had to be tacked onto the old [2]. Or, to be more specific, a new extension had to be tacked and layered onto the rapid advancement of temporality so that the epilogue of every life was at least capable of being acknowledged. To try to pray a loved one out of Purgatory via the Office of the Dead would have meant interacting with and trusting in the eternal as both a physical space and a system of time that existed not to be comprehended, but rather to be communicated and pleaded with. Religious time was temporal and eternal, even if those things had to exist in a compressed, parallel structure that put differing demands on their momentum. Many Office of the Dead miniatures remain close to the medieval Christian’s earth and therefore close to his or her temporality.

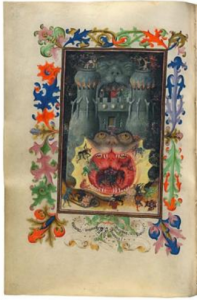

In some cases (as with the Connolly Book of Hours), such closeness is expressed through the limitations of bodies and graves, and yet other books of hours allow Hell itself to break the earth’s crust and assert the presence of a time-scape that, like Purgatory, is looming just within reach of the temporal reality.

The gaping maw of the “other time” in the Hours of Catherine of Cleves does not do away with the vague character of Purgatory, though. The virulent red and horror of the image capture the inherent unknowability of time after death and the hole in the earth serves as a visual access point that works in tandem with the religious/spiritual access provided by dedicated prayer. On “earth” or in the mind, the existence of eternality is dark and yet certain, tampering with the medieval Christian’s delicate conception of the temporal.

So, the temporal does not precede the eternal, and neither does the eternal precede the temporal. They are the compact layers of a singular expression of time and, because that expression has been dictated by the ideas of the church, both layers can boast religion as their foundation. The “collapse” of the two that I referred to in the beginning is obviously a product of placing the Hours of the Virgin and the Office of the Dead between the covers of a single book, but that’s not where the theory ends. Structurally speaking, the two texts build a strange version of a clock. The outward clock, the hands and numbers and glass enclosed face, would represent the Hours of the Virgin (temporality). The hidden gears and mechanics would represent the Office of the Dead (the eternality of Purgatory). The two must coexist to make a functioning portrayal of time, and yet the average individual will look at a clock and appreciate and build their lives around its explicitly visible movements while casting vague hopes in the direction of its deeper workings. That being said, I will not draw the complications of the clock maker into this, unless that clock maker is God, and I fully understand that such clocks would not be available in the average medieval home.

[1] Reinburg, Virginia. “Prayer in Books of Hours.” Time Sanctified: The Book of Hours in Medieval Art and Life. New York, George Braziller Inc., 1988. pp. 39-44.

[2] Wieck, Roger S. “The Book of Hours.” The Liturgy of the Medieval Church, edited by Thomas Heffernan and E. Ann Matter, 2nd ed., Kalamazoo, Medieval Institutes, 2005, pp. 431-68.