Welcome to the strangeness of Baltimore, Walters Art Gallery MS W.441! A few things set this manuscript apart from the everyday Book of Hours. For one, this Book of Hours lacks the very thing that makes Books of Hours what they are: the Hours of the Virgin (Weick 60; Reinburg 209). MS W.441 instead centers around the Hours of the Passion, making it more Christ-based (for more on this absence in manuscripts, see Christian Gallichio’s post). The second major deviation in this manuscript is the illuminations. For the most part, they’re modern.

According to the manuscript description, the text was written in the sixteenth century in Flanders. Many of these pretty illuminations, however, were commissioned by John Boykett Jarman in the nineteenth century. William Caleb Wing, the talented modern illuminator of this manuscript, engaged with original medieval borders to create border illuminations and full-page miniatures.

Wing was no stranger to working with medieval manuscripts, even “damaged surviving manuscripts,” for Jarman (Backhouse 80). He also worked for other commissioners as a professional facsimilist, and a pretty convincing one at that (Furlong 7). In addition to MS W.441, he illuminated borders for Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum MS 193, and Yale, Beinecke MS 287A, only a few on a list of his contributions. Wing’s artistic calling card is beautiful floral illuminations on striking gold backgrounds. Through these examples and other borders of MS W.441, we can see that he utilizes bright colors and subtle shadowing to make these lifelike images pop. Wing’s floral imagery will be important to the Hours of the Passion’s illumination framework.

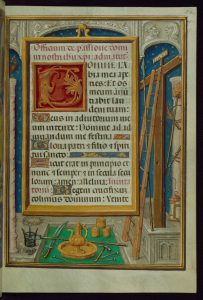

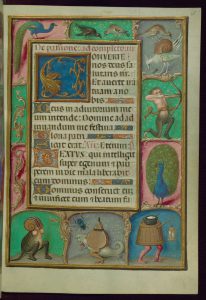

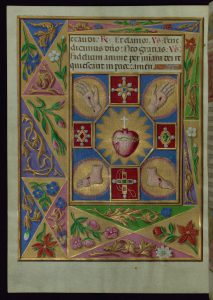

Before we go any further discussing Wing’s borders, a couple of things need to be noted. I’ll be looking at three different border illuminations that tell Jesus’s Passion through illustration and order, and I’ll tackle it in order. On 32r, Wing illuminates the arma Christi, instruments used in Christ’s torture; this folio correlates to the hour of Matins, opening the Hours of the Passion. 68r, an original border ending the Hours with Compline, shows grotesques dancing around the text. Fols. 32r and 68r act essentially as book-ends as they start the first and last hours, but this isn’t where our picture story ends. Another modern border by Wing, 71v, depicts the five wounds of Christ and ends the entire section of the Passion, coming just before the Mass of the Five Wounds. It displays a variant of Wing’s floral and gold signature border.

Wing’s depiction of the arma Christi on 32r is almost like an Easter egg hunt — you have to find them all and figure out what parts of the Passion they’re referring to. From my initial count, I found four major symbols. On my latest count and consultation with The Arma Christi in Medieval and Early Modern Material Culture, I brought that number up to thirteen, with two obscure symbols making the total fifteen: the hay fork and three gold containers.

These instruments symbolized Christ’s triumph over death in the early Middle Ages, but by the twelfth century, they came to be “mementos” of the Passion for us to meditate on Jesus’s suffering (Cooper and Denny-Brown 5). The arma Christi are man-made, except for Peter’s rooster, although he is the reason the rooster crows. Every one of them was either created to be cruel or was used in a cruel way against Christ, suggesting that as creators, we are only capable of making harmful objects. For Jesus to use man-made instruments to combat death, he has to address our evil ways and reclaim our cruel creations as his own to save us, ultimately transforming the instruments into good things.

The same can be said about the grotesque border, which Wing may have retouched although it is not specified; the text is original. The grotesques of 68r are mish-mashings of animals and everyday man-made objects, like buckets, bellows, and bowls (oh, my!). Some of the grotesques are mixings of real animals, with a strange fascination with snails. My personal favorite is what I fondly call the “quail snail” in the top right corner.

Perhaps the intent of the original illuminator was to show off his art and imagination skills. I believe that the grotesques, in conversation with Wing’s arma Christi border, represent sins. The original illuminator’s combination of God’s creation and tools suggests man’s appropriation of creation. Wing’s border seems to critique the original border because the grotesques have nothing to do with the text. This may be why Wing chose to illuminate the Matins prayer. Wing’s arma Christi folio makes a point to be directly involved with the text. Jesus reclaims the man-made arma Christi, so these instruments become holy. The man-made grotesques, however, don’t fit the Passion narrative at all, so they must be removed. In this way, the modern illuminator may be chastising the original one, calling him out as “playing God.”

The grotesques are unnatural and unholy because they weren’t created by God, disregarding the two peacocks and a couple of birds. The peacocks, however, could represent pride in its purest symbolic form, one of the seven deadly sins. The two grotesques mish-mashed with tools showcase man’s creation, far less magnificent than God’s.

They struggle with elements of humanity. The bottom left creature, a cross between a snail and armadillo, is wearing slippers, and the faun on the right wears a ribbon around its waist, almost like they are trying to gain humanity by wearing clothes, which is arguably what makes humans a step-up from animals (Bliss 223). The snail-armadillo also has exposed female breasts, perhaps drawing on lust. The faun is the most human, with a human torso and head, and has the mental capability to use weapons, suggesting that humans are instinctively wrathful. Fauns are also very lusty creatures. Anthony Bale, in his explanatory notes to The Book of Margery Kempe, suggests that bellows, seen in the bellows fish, could represent lust (249). A bellows’ role of “blowing air” also implies boasting, an offshoot of pride.

With all of these grotesques in mind, several questions arise. What makes a human? Are these grotesques reflecting us at our very worst? These are questions that may never have answers, but Wing sets them into motion.

Wing’s arma Christi border provides some insight into how the story of the Passion works in the illustrated form. It interacts with the grotesque border by creating an almost cause-and-effect scenario. The grotesques reflect something foreign to us, as sin was originally supposed to be. Jesus, through his instruments, destroys the sin inside us by trapping the grotesques within their thick borders and using the arma Christi to eliminate them.

To complete the destruction of the grotesques, Wing inserts 71v at the end of the Passion section. 71v mimics the bordering and colors of 32r, but the grotesques are replaced by Wing’s signature flowers with gold highlighting, returning to his artistic order. The five wounds of Christ are present with a glow around them to convey holiness and victory. They jive with the narrative Wing creates to reflect the Passion — how Jesus retains his wounds from our man-made weapons to save us from our man-made sins.

To further illustrate this point, 71v shows the end of a prayer to save souls from Purgatory (“Fidelum anime per miam dei requiescant in pace: amen”), which suggests that Jesus, through his Passion, succeeds in freeing us from sin. Because the instruments of the Passion destroy the grotesques via their removal from the illuminations, Christ had to suffer for our sins, and we should reflect on his ability to do so, going full-circle to convey Wing’s interaction with the original illuminations without removing them.

Works Cited

- Backhouse, Janet. “A Victorian Connoisseur and His Manuscripts: The Tale of Mr. Jarman and Mr. Wing.” The British Museum Quarterly, vol. 32, no. ¾, Spring 1968, British Museum, pp. 76-92. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4422995. Accessed 30 October 2018.

- Bale, Anthony, translator. Explanatory Notes. The Book of Margery Kempe. By Margery Kempe, Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Bliss, Sylvia H. “The Significance of Clothes.” The American Journal of Psychology, vol. 27, no. 2, April 1916, University of Illinois Press, pp. 217-226. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1413173. Accessed 31 October 2018.

- Cooper, Lisa. and Denny-Brown, Andrea. The Arma Christi in Medieval and Early Modern Material Culture. Ashgate, 2014.

- Furlong, Gilliam. “Book of Hours from the late 15th century, adapted for the Victorian market Officium Beatae Mariae Virginis.” Treasures from UCL, UCL Press, 2015, pp. 42-45. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/j.ctt1g69xrh.13.pdf. Accessed 31 October 2018.

- Reinburg, Virginia. French Books of Hours: Making an Archive of Prayer, c.1400-1600. Cambridge UP, 2012.

- Walters Art Museum, W.441, on line description © 2011 Walters Art Museum, used under a Creative Commons CC0 license: https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/.

- –, W.441, fol 32r, © 2011 Walters Art Museum, used under a Creative Commons CC0 license: https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/.

- –, W. 441, fol. 68r, © 2011 Walters Art Museum, used under a Creative Commons CC0 license: https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/.

- –, W.441, fol. 71v, © 2011 Walters Art Museum, used under a Creative Commons CC0 license: https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/.

- Wieck, Roger. Time Sanctified: The Book of Hours in Medieval Art and Life. George Braziller, 2001.