I really do love teaching first-year, especially first-semester students. They are eager. University is still their oyster. Everything is there to learn — including things about themselves. They may get lost, or not turn in work on time, or call me “Mrs” instead of “Dr,” but because they are still learning the ropes they are also more willing to break boundaries with alacrity.

UGA runs a First-Year Odyssey (FYO) program, in which full-time faculty teach a one credit, once a week course in their research area to a class of fifteen students. The goal is to introduce first-years to the research work that their professors do, but for many profs it’s a chance to have fun with their research. This is the third year I’ve taught a medieval manuscript FYO, and it never gets old.

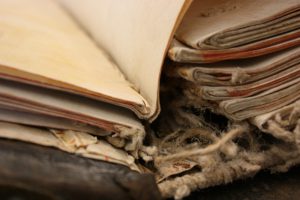

An example from today’s first visit to the Special Collections library. We ended the day by looking at the showpiece of the UGA medieval collection, a 1507 gradual from a nunnery in Spain, near Burgos. It’s in its original cover, complete with elaborate bosses and broken clasps; its bilingual frontispiece gives its provenance and date; it’s got musical notation and a lovely donor-portrait initial (shown above); its binding is broken terribly; and it’s BIG. Like, the other side of 40 pounds big. I don’t even think of shifting it without help. When I showed this manuscript to my upper-division students two weeks ago, they could not for the life of them figure out why the book would be so gigantic, and why the script and notation would be proportionately large. (Bless your hearts, guys.) My first-years today, however, were on it like that: it’s designed for a community of nuns to all sing from it together, while they are sitting in the choir. It’s meant to be read from afar, just as my students today and last week were circled around, looking at it today.

The gradual is one my favorite pieces to show students, even though I know I am doing damage to its binding every time I open it. Its mixture of Latin and Spanish, its Harry-Potter-esque cover, its intriguing if illegible (to me) musical notation, its oversized glories all make it immediately accessible to students, even first-years who are still learning when “medieval” is. They can decipher the function of the bosses and clasps on the cover, read the Spanish (once they know how to recognize a long S in the wild), and interpret the historiated initial with only minor guidance from me. And they can even suss out the original purpose of the manuscript without reading a word of the contents. And that’s as fun as teaching gets.