The Book of Hours is really cool because it was personalized for the individual patron. The individual could pick and choose what prayers, illuminations, sections, and saints they wanted inside their Book of Hours, but also it can be personalized through hand written notes inside of it. These annotations can tell us stories of possession, but the prayers inside the Book of Hours do as well in a more conventional way. The prayer is personal because it is being said in private, sometimes having the patron’s name substituted in the prayer, but it is also conventional because medieval people borrowed words from others and they made these words their own through reciting the prayers. (In other words, the reader is repeating a prayer that has been said many times before, but because the reader is reciting it, it becomes personalized to that individual.) This leads us to the idea of polyvocality. These prayers are connecting the individual to the past by using these words that have been spoken before, even though they are making these words their own. Unlike the spontaneous prayer that we use today, these ritualized prayers connected the medieval people to the past by repetition.

Sometimes the individual wouldn’t write all inside their Book of Hours because more often than not, families passed down their book of hours to younger generations. In that way, it doesn’t seem as personalized to you individually if you’re just using it for the time being and can’t write in it, but through these prayers, the person owning the book at that time would still be able to make it personal to them. If you’re getting a book of hours that was passed down to you, you couldn’t pick what prayers, illustrations, saints, etc. that you wanted it to contain like the first owner could (although you could add or take out some things), but by vocalizing the prayers inside of it, you are really making it your own. Although there could be a lack of annotations, it does not mean that the book of hours wasn’t used in a personal way.

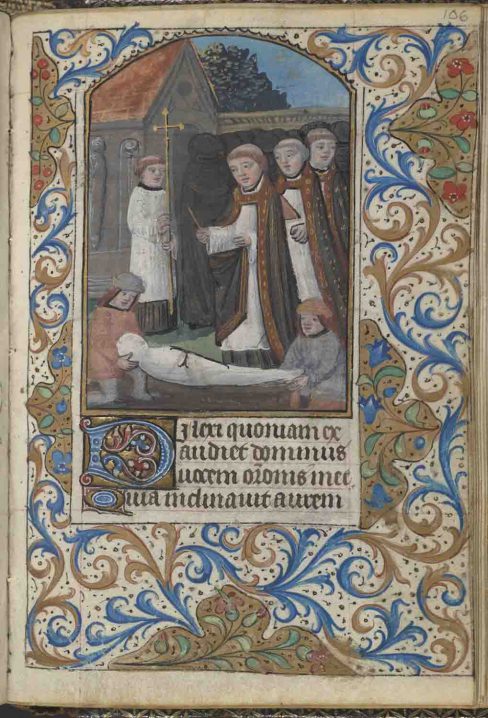

Now let’s take this idea of personalization and polyvocality and bring it into the Office of the Dead, which have my favorite illustrations as shown here from the Connolly Book of Hours.MS.1986.097

There is usually just one illustration in the Office, but the illustration can range from a burial scene to the Archangel Michael fighting a demon over a person’s soul. This illustration here is a burial scene that shows a body wrapped in white cloth being put into the ground by two men, with three monks to the right, another monk to the left holding a gold cross, and creepy black hooded figures in the back which I presume are mourners. This illustration is interesting because you can’t see the faces of these hooded figures unlike other burial scene illustrations I’ve seen.

Now that you’ve been introduced to the Office and the creepy illustration, lets venture to Matins (the second hour of the Office) and the nine lessons from Job that can be read on this page of the hypertext hours, since I’m not going to quote the whole thing. The nine lessons occur in the first, second, and third nocturne. These nine lessons consist of despairing verses from Job asking for pity and mercy from God, such as “The flesh being consumed, my bone hath cleaved to my skin: and there are only left lips about my teeth. Have mercy upon me…” (the 8th lesson, Job 19). Job is the one speaking, but it’s as if the loved one you are trying to get out of Purgatory is the one asking for mercy and help. You could be saying this prayer for your loved one on your own in private, or a monk or priest would be saying these prayers for your loved one and you would be the one listening. In this way, we have an interesting form of polyvocality because we have the original voice of Job through these verses, you or a monk are then reciting these same words so it becomes personal to the individual, and then we have the imagined voice of your loved one who seems to be screaming out for mercy in Purgatory through Jobs words. There are lots of layers going on here when you think about it!

Just the thought of your loved one being in Purgatory was agonizing to medieval people, so could you imagine on top of that having to say or hear these despairing verses from Job and imaging your loved one going through the same thing? There is no hope present in these lessons up until the eighth lesson where Job says, “For I know my Redeemer liveth”, and here we finally get some resolution. As you can see, through the personalization of prayers (like the example I just gave from the lessons of Job in the Office of the Dead) polyvocality naturally comes into play. By making a prayer inside a book of hours personal to you, you are adding a voice (your voice) and connecting with the past.

- Lerer, Seth. Literary Prayer and Personal Possession in a Newly Discovered Tudor Book of Hours. Studies in Philosophy, 109(4), 2012, pp.409-428.