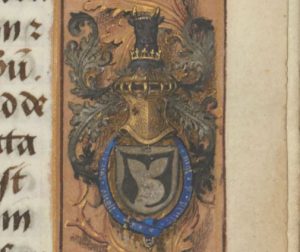

This particular Book of Hours is London, British Library, Add. MS 54782. It’s often called “The Hastings Hours” due to its only known owner during the late Medieval Period: William, Lord Hastings. Hastings’ arms appear four times in the manuscript. However, since they appear to be added in and not an original ornamentation, it’s possible that the book had an owner before him. Potentially, it was given to him as a gift at some point, but there are only speculations as to who that might have been, though it’s possible this book was given to him by King Edward IV, of whom Hastings was a close friend and courtier.

Before delving into Hastings’ book, however, it’s necessary to learn a little about him. Luminarium.org, while an online anthology of English literature, offers an encyclopedia of the people and places mentioned in its works, which is where I gained the following information about Hastings:

William, Lord Hastings was born into a high-ranking family around 1430. Hastings would grow up just in time to participate in the Wars of the Roses, a series of civil wars between the Houses of York and Lancaster. When choosing a side, Hastings swore fealty to and served Richard, Duke of York, in exchange for an annuity. The House of York gained the throne after a decisive victory in 1459, and Richard became the royal heir. But, nearly two years later, Richard would meet his death in battle, and Richard’s eldest son, Edward, with whom Hastings had become close with, would be crowned Edward IV in 1461. Immediately and over the following years, Hastings was awarded several titles, becoming a baron and given portions of forfeited estates from the Lancastrians.

According to Luminarium, Hastings is characterized as having an unshaken loyalty to Edward IV, of which he was praised repeatedly throughout his life. He would even follow Edward IV in exile in 1469 to the Continent and in Edward’s return the following year with forces to retake the throne and secure his reign. His loyalty also led him to escorting Edward IV’s son, Edward V, to London to be crowned king after Edward’s death. However, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, the youngest brother of recently-deceased Edward IV and uncle to the child-king Edward V, would claim that the Queen’s children were illegitimate (Edward having married her instead of the contracted spouse) and accuse the Queen of sorcery (on account of Richard’s withered arm or some such). On these grounds, Richard effectively delivered the figurative and literal killing blow: accusing Edward V’s supporting party of treason. Hastings, as Edward’s most loyal supporter and strongest obstacle to uncle Richard, was immediately beheaded, without trial, outside the Tower of London. Edward V and his brother, yet another Richard, would also be killed, though the details are fuzzy about their deaths. Uncle Richard was crowned Richard III not long after.

This particular account of Hastings seems to paint him into a martyr for the House of York. For a different view of Hastings’ execution, you can check this Murrey and Blue blog post detailing potential reasons that Hasting’s execution by Richard might not have been unjustified. For all I know, Hastings was just as ambitious as Richard III. But, for now, despite the intriguing rabbit hole of Hastings’ potential guilt, it’s best we move on to the manuscript.

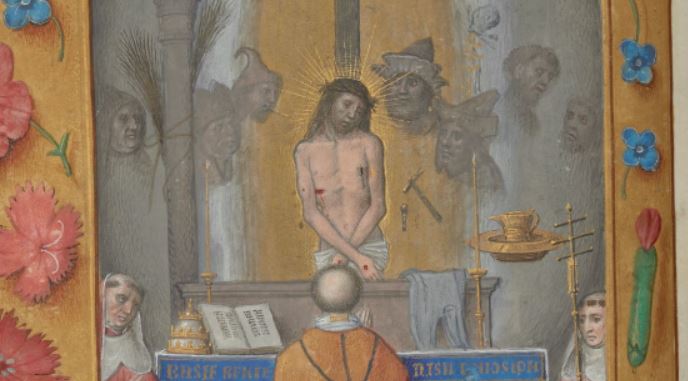

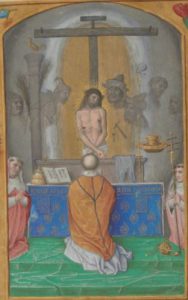

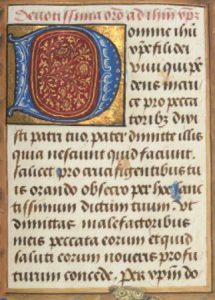

The Hastings’ Hours is a particularly large manuscript, comprising of 300 parchment leaves divided into multiple sections besides the expected Hours of the Virgin. However, the text I’ll be focusing on is a single prayer in a miscellaneous Devotions section beginning on folio 19r. It’s a devotion to Christ, not an uncommon topic in the Christian faith, but this prayer was placed as the first in the section, already near the front of the book, probably for easy reference. Additionally, each of the devotional prayers of the section are given special treatment in the form of a lovely full-page miniature, this one being no exception:

Opposite the miniature, the prayer itself:

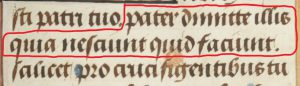

However, what makes this prayer to Jesus special is the line that it sets its foundation upon: “pater dimitte illis quia nesciunt quid faciunt.” This is the Latin translation of one of Jesus’ last utterances during the Passion: “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.”

What might a prayer that includes this be doing?

This prayer, ultimately, is asking for the salvation of one’s enemies, and it would be performed in a similar circumstance. Not crucifixion, of course, but in the trials any person might face in life, particularly the tribulations that are imposed by others. This is a fitting prayer for the Book of a political martyr, don’t you think? However, one would assume (as certainly I did before being corrected) that the precant (performer) is channeling Jesus’ words in order to forgive his enemies, but this isn’t the case. Interestingly enough, while it does include the “pater dimitte” saying, it’s not presented in the performer’s voice. The saying is actually quoted in context and explained to a “you,” who is Jesus, of course. But, the precant more or less goes on to ask that Jesus provide for the necessities of his enemies: to care for them and ultimately provide what’s necessary for that person to attain salvation.

A prayer including Jesus’ “pater dimitte” that doesn’t directly offer forgiveness from the persecuted party is interesting. It’s possible that the author of this prayer merely considered the performer’s forgiveness irrelevant, that Jesus’ forgiveness of sins is the only forgiveness worth receiving. Though it is a Christian principle to forgive one’s enemies, only Jesus’ forgiveness of sins can save someone from condemnation.

But, this prayer’s content is about being the object of persecution under the assumption that it’s unwarranted, which brings me to the main interest I had in this prayer: anyone could place himself in the “right” by performing it. While the precant may not be putting himself directly in the place of Christ, the prayer essentially recalls Jesus’ example of forgiveness and asks that that forgiveness be extended to the performer’s enemies. As such, by asking that Jesus ultimately provide the needs for the enemies’ salvation, the prayer assumes that the precant is innocent and that his enemies are evildoers, the malefactors (“malefactoribus”) in a pseudo-Passion. How many aristocrats or politicians might have performed this prayer while under pressure from their rivals? I like to think that Hastings might have muttered this prayer under his breath as he went to the chopping block. But, what I’ve read of Hastings has heroified him in my mind, and there are cases to be made, like in the blog post I mentioned earlier, that Hastings was incredibly ambitious and a possible conspirator. I’m not sure that would justify him losing his head, but let’s not make a saint of him, yet.

This prayer is a devotion to Jesus and based upon one of his last utterances. But, there are countless prayers to Jesus in Catholic liturgy, and this is likely not the only ever prayer of Christ’s “pater dimitte” utterance. Books of Hours are like personalized, liturgical anthologies, and just as anthologizers have to decide which texts go into their works, whoever commissioned this Book purposefully chose this prayer and placed it near the front for easy reference. Looking at this prayer, we should wonder, who or what determines that a prayer like this makes the cut?

By: Zachary McCannon