By: Georgia Earley

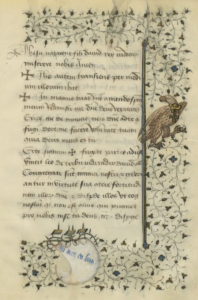

As discussed here, each member of our class was asked to ‘adopt a manuscript’ this semester. When I heard about this assignment, I was thrilled. This was a chance to find a manuscript that really spoke to me, and to use all of the knowledge I had gained about medieval book production to really dive into it. Of all of the choices, British Library, Egerton MS 1070 stood out to me for one very specific reason: this picture.

I loved how shocking and gory it was, with a king seemingly risen from the grave, and I had to know more. Who was the owner of this creepy manuscript? It turns out that Egerton 1070 was owned by René d’Anjou, a French titular king during the Hundred Years War born in Angers on January 16, 1409. He held many titles throughout his lifetime, beginning with Duke of Anjou. From age 13, Rene was raised by his grand uncle Cardinal-Duke Louis I of Bar. René learned the arts and got an education under Louis, and upon this uncle’s death received the duchy of Bar. This title was contested by Antoine de Vaudemont, the nephew of the late Cardinal-Duke Louis. Antoine was backed by Philip the Good of Burgundy, an enemy of René’s family. This family hostility can be traced back to the death of Louis of Orleans, René’s first cousin once removed, at the hands of John the Fearless of Burgundy. This led to hostility, and ultimately placed the house of Anjou on the side of the French crown, and the house of Burgundy on the side of the English. René had no choice but to fight Antoine for the title, and for his family’s honor.

On July 2, 1431, René lost the battle to Antoine and received a scar on his lip that seems to be present in this portrait of him.

Antoine had won, but because of his support, Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy demanded that René be handed over to him. René d’Anjou spent about six years imprisoned, and during this time managed to receive three new titles including Count of Provence. René was set free in 1437 after paying a large bail, a monetary loss from which he would suffer all of his life.

Before his imprisonment, René had received the duchy of Lorraine by marrying Isabella of Lorraine. In 1442, his wife Isabella died, and in 1454 he married Joan of Laval. He spent his entire life trying to keep all of his titles, and despite great effort ultimately failed. The title of ‘Duke of Anjou’ was given over to the French crown when he died. That being said, René d’Anjou had much greater success in non-militaristic fields. He was a successful author of many works, including an instructional guide on conducting a successful tournament, a romance, a religious allegory, and even love poetry.

After learning so much about the owner, it was easy for me to see his touches everywhere. His motto is featured prominently throughout Egerton 1070, and the incarnation of death on folio 53r is representative of René himself. Interestingly, the manuscript was originally made around 1405-1410, during the time of René’s birth, for someone other than him. René would have acquired it later and added his own marks around 1442-1443. These additions include several full-page miniatures (such as the one on 53r), a poem, and several prayers, some of which mention René by name.

The idea that René had added his own material to a previously completed Book of Hours was extremely fascinating to me, and I had to learn more. I headed to the library to try to find some information about the things René had added to this manuscript. At the library, I discovered that René had not just one famous Book of Hours, but two. The second is Bibliothèque Nationale de France, MS lat. 1156A, now at the National Library in Paris, and was created for René around 1435. It is very lovely, and contains a portrait of René (see above) and also of his father.

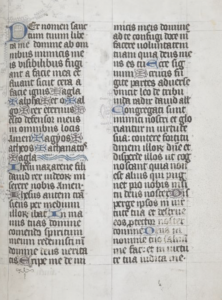

It was great news to discover this, because I could then compare the added material in Egerton to the other manuscript and see if there were similarities. Lo and behold, there were. On folio 147 of lat. 1156A, there is a prayer that matches almost perfectly with an added prayer on folio 14 of Egerton 1070, and this prayer is filled with Passion material.

And a sail with René’s motto “en dieu en soit” surrounded by a foliate 3 sided border.

source here.

It is in a different script than most of the Latin 1156A manuscript, which is interesting, because it suggests at least two different scribes and perhaps several rounds of additions. It still seems to be part of the original manuscript production because the decoration is identical to the rest of the manuscript. Because it is in both of René’s Books of Hours, I decided that this prayer must have been incredibly important to René at many different times in his life, and I wanted to know why.

with a line fill. source here.

The prayer is made up of many fairly common antiphons, along with the entirety of modern Psalm 54, but this exact combination has been impossible to find in any other manuscripts thus far. We seem to have a prayer that is original to René. What is interesting is how René addresses Jesus in the prayer, and how he ties Old Testament Psalms into the New Testament Passion story. He begins “Ihesu nazarene fili David, rex iudeorum miserere nobis Amen,” or “Jesus of Nazareth, Son of David, King of the Jews, have mercy on us Amen.” This echoes the title Jesus was given by the Romans when he was being crucified, as seen in John 19: 19-22, but interestingly adds ‘son of David,’ which adds extra emphasis to Jesus’ royal lineage.The added title makes Jesus an actual king, and turns ‘King of the Jews’ into a birthright and not a joke played by the Romans. This could have been important to René, who would have related more to Jesus as a king rather than as a carpenter’s son.

The next section is “But Jesus passing through their midst went His way.” This antiphon is confusing to me. It seems to be unrelated to this calling out to Jesus in the previous line, and is usually said during second vespers in the Magnificat (a song of praise taken from Bible passages). René begins by lavishing Jesus with titles and begging for mercy, but this does not carry that tone at all. However, it references Luke 4:24-30 when Jesus left a crowd of people trying to persuade him to do miracles. Perhaps this antiphon was a way to remind René that no matter how much he prayed, Jesus ultimately made the decision to do the miracles or not. It was a way to show His power through passiveness.

Many Bible passages are recited or read so that the ‘I’ in the verse is not only the Biblical speaker, but the reader, and everyone else who has ever read the passage. The words of Jesus would not be off limits for prayer, but the opposite. They provided an example and a model for how medieval Christians hoped to pray. This is shown very nicely in the next line of our prayer: “In manus tuas domine comendo spiritum meum” or “into your hands, oh Lord, I commend my spirit.”. This brings us back to the cross, specifically Luke 23:46, as these were Jesus’ last words before he died. Instead of Jesus crying out to God, the words are inhabited by the reader. René is giving his spirit over to the Lord, and in a way becoming Jesus, which is a nice tie in for the beginning of the prayer, in which René paints Jesus as a royal figure. Jesus represents how to be a good king, but he also represents how to be a good king even when everyone is against him.

The rest of the prayer evokes Jesus and God, begging for help against enemies, something that would have been dear to René’s heart, as he was seemingly lacking in military skills. Even the chosen Psalm that finishes the prayer relates back to God scattering enemies and saving the speaker.

I hope to figure out more about these manuscripts in the future, but one thing that this prayer has taught me specifically is that Passion material could be used however one wanted to use it in the Middle Ages. It was something everyone knew, and a way to feel more connected to Christ, even if you were René, a not-so-successful king with a really cool beard.

Works Cited

- Gibbs, Stephenie Vierek., and Kathyrn Karczewska. The Book of the Love-Smitten Heart by Rene Anjou. New York: Garland, 2001.

- Harthan, John P. The Book of Hours. New York: Crowell Company, 1977

- “Jesus Autem Transiens per Medium.” Jesus Autem Transiens per Medium | Cantus Manuscript Database. Accessed October 24, 2018. http://cantus.uwaterloo.ca/chant/218150.

- Laycox, Monty R. An Intertextual Study of the Livre Du Cuer Damours Espris by Fifteenth-century French Author René DAnjou. Lewiston: Mellen, 2007.

Appendix

- “Egerton MS 1070.” Digitised Manuscripts. http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Egerton_MS_1070.

- “Horae Ad Usum Parisiensem [Heures De René D’Anjou, Roi De Sicile (1434-1480)].” Gallica. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b6000466t/f317.planchecontact.