Listen, being a grad student can be a drag. You’re either sitting at your desk writing or squinting at tiny gothic rotunda for hours on end. You look for excitement wherever you can get it. So when I took a course on medieval books this semester, can you blame me for craving a mystery?

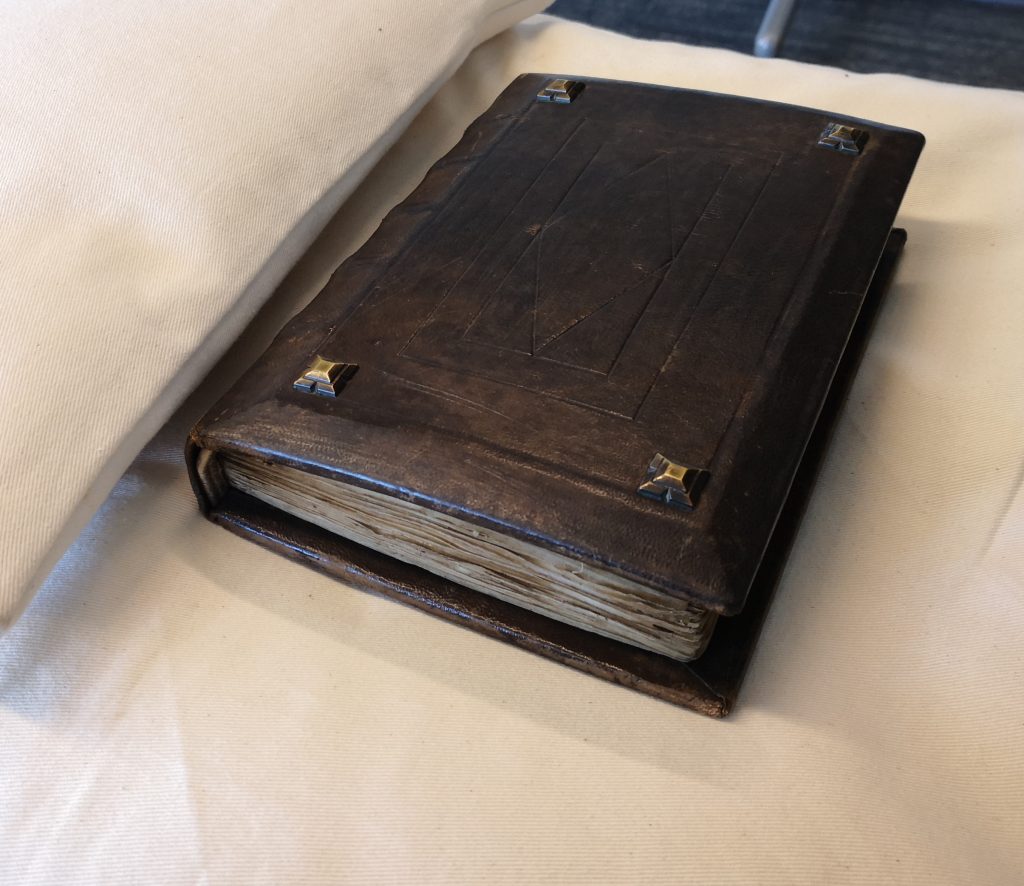

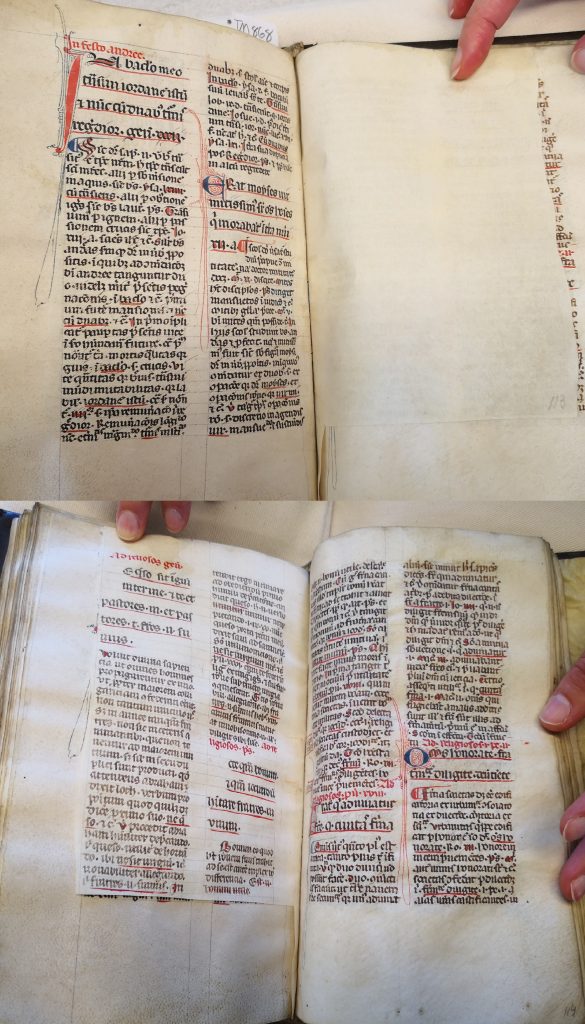

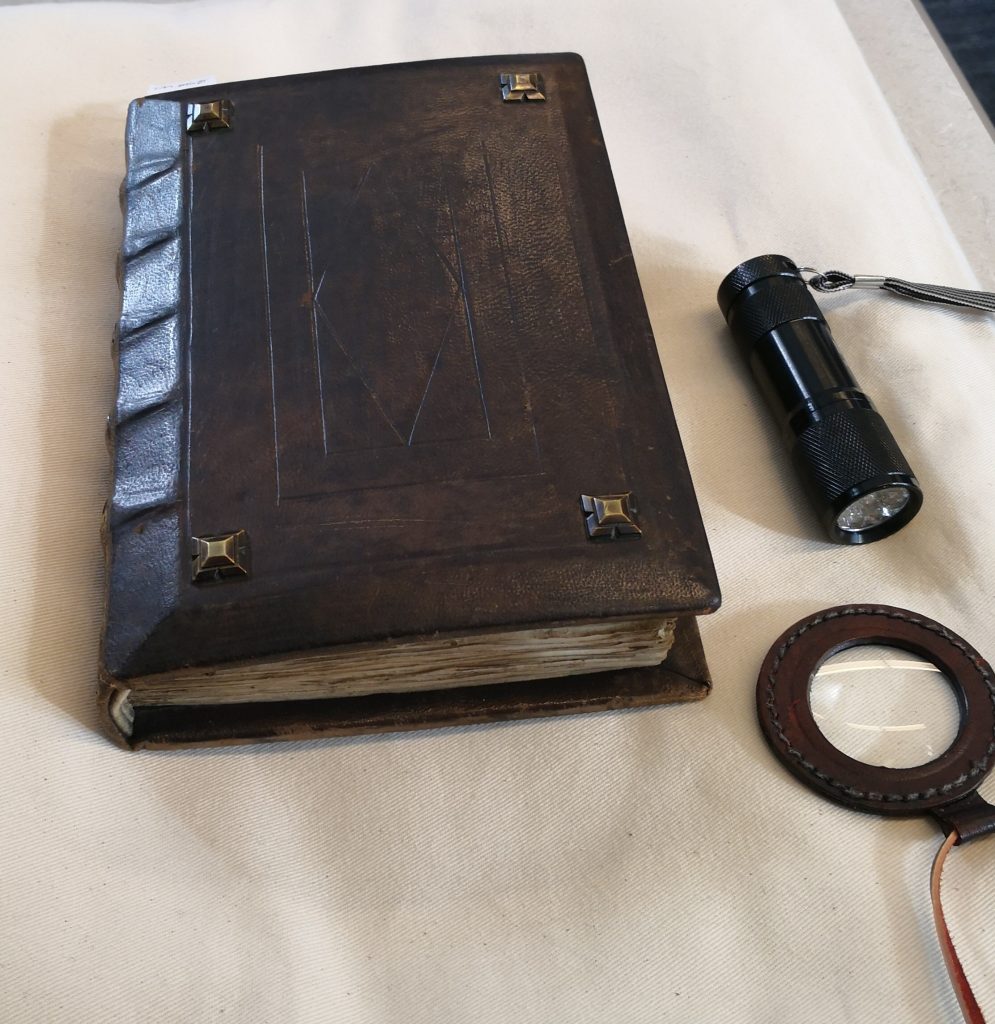

There is always going to be something weird about an 800-year-old book. The fact that it even survived this long is wild. So after you do all the mundane data collection on a medieval book, a mystery is bound to reveal itself. It may not be ground breaking, and often you will just hit a dead end. But even knowing there’s nothing there is answer enough. Take my little adventure with Les Enluminures’ teaching manuscripts (yes, those are a thing!), Ms. TM868. It is a book of sermons dating to 13th-century France and attributed to Nicolas de Gorran. I sat down and did the grunt work. And friends, the quiring made no sense. This whole book is a weird little compilation of oddities.

Let’s back up. A quire is a “gathering” of folded sheets known as folia (sing. folio). Scribes copy their texts onto these prepared blank quires. Once they reach the end of a quire, they will usually write the next word of the text at the bottom of the page (called a catchword) so the quires can be matched up later and bound together into a codex (or to us, a book). A quire usually consists of an even number of folia (2, 4, 8, etc.; see Werner 42) You know when you rip a sheet of paper out of a bound notebook? You expect its “twin” to fall out the other side, right? That’s how quires work. Keep that in mind.

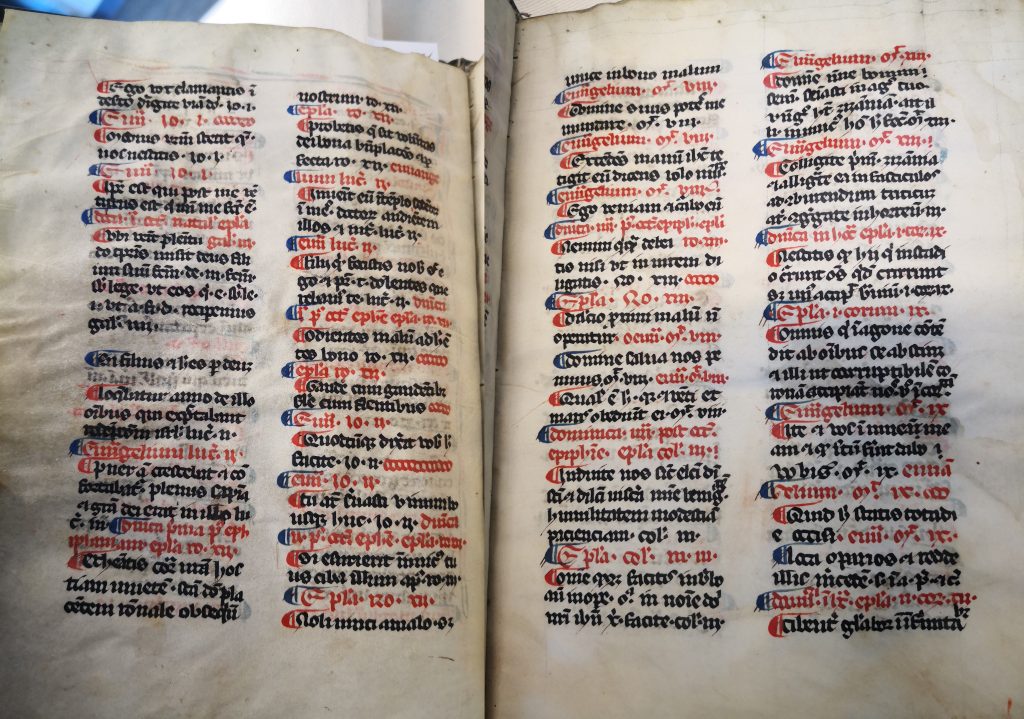

The Sermons contains 136 folia in total, a nice, even number. And all the catchwords seem to line up. The book even has a table of contents (thanks scribe!) Real talk: If a book has a table of contents, do yourself a favor and look at it. It can give many clues about what the author(s) intended, even if it doesn’t line up with the actual contents of the book.

Because yup, you guessed it. An afternoon of checking the table of contents against the actual sermons revealed that they are “out of order”. There are three main sections to the book (let’s call them Sections 1, 2, and 3), and at some point, someone rearranged them.

Now, knowing virtually nothing about Dominican sermon construction, I could not tell you why. But I could try to figure out how the book was arranged from the physical evidence of the quiring and the text (meaning the actual ink on the leaves, not the sermons themselves, which are in heavily abbreviated Latin – I decided not to do that to myself, as an act of self-care).

The Quiring

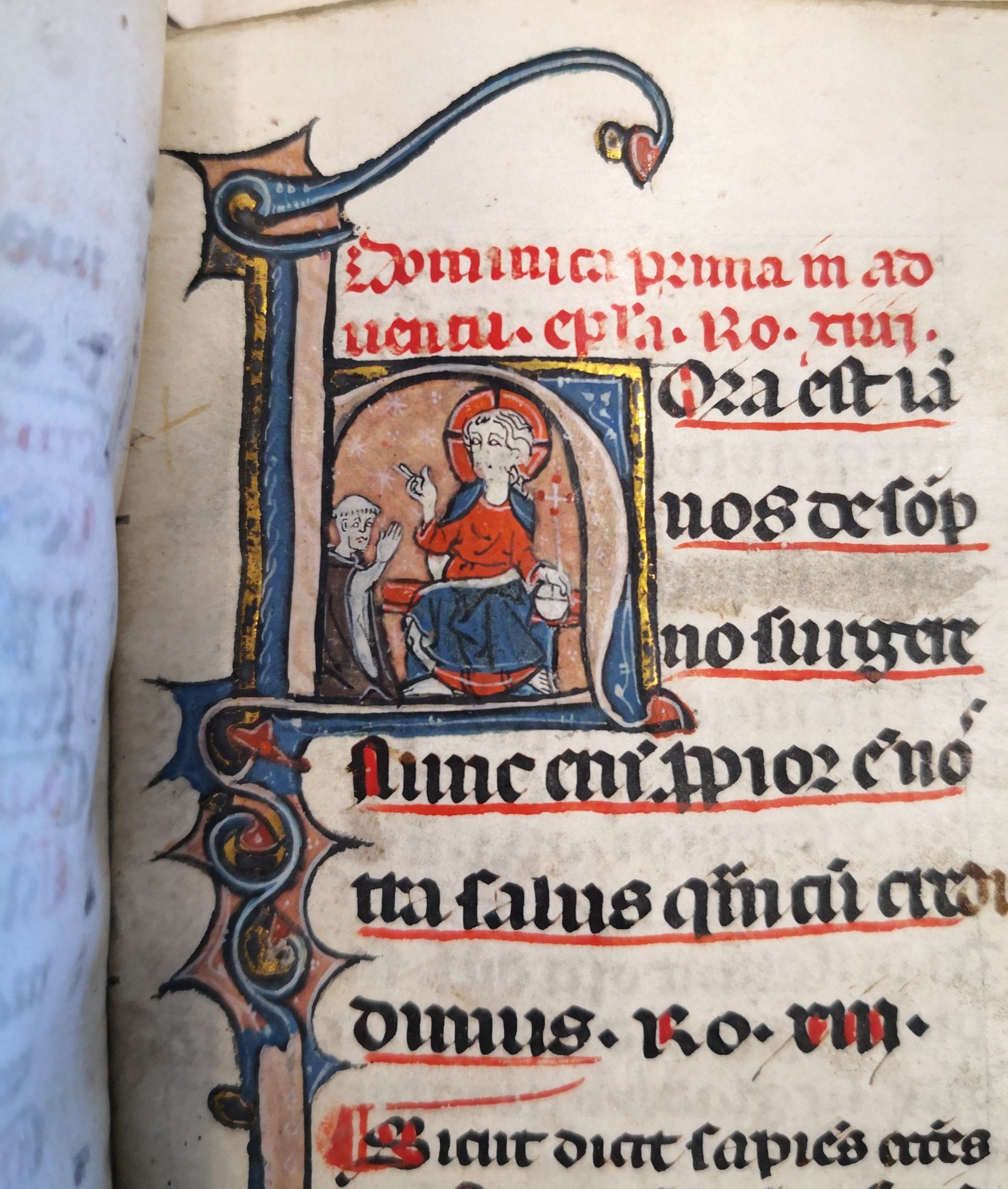

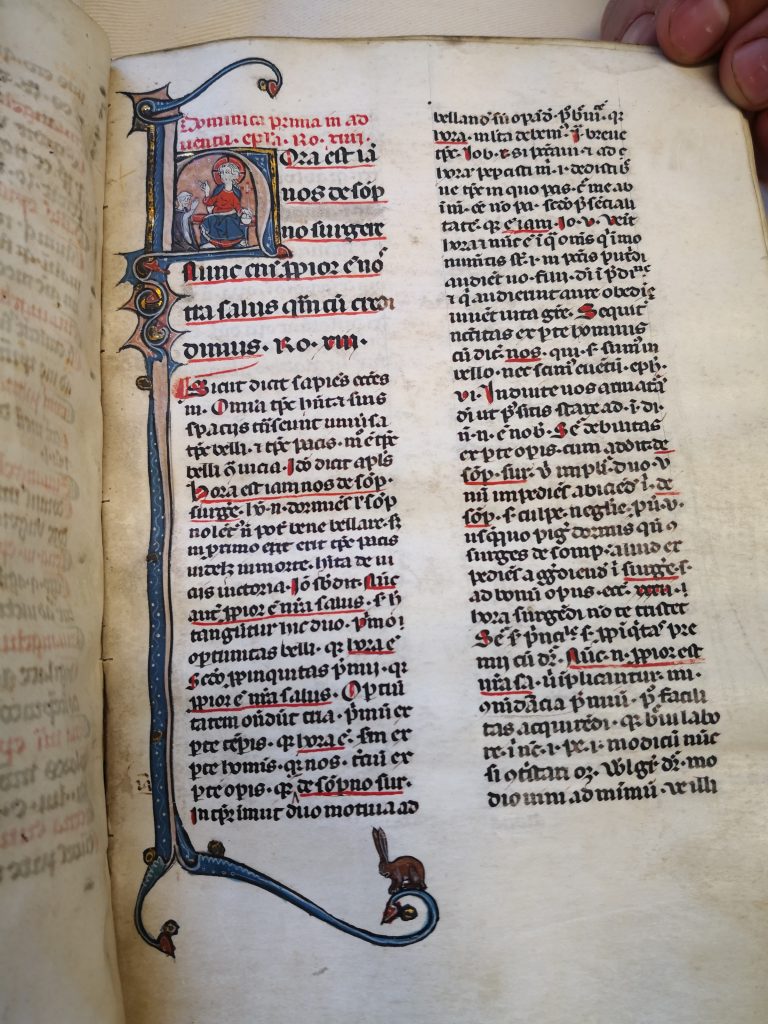

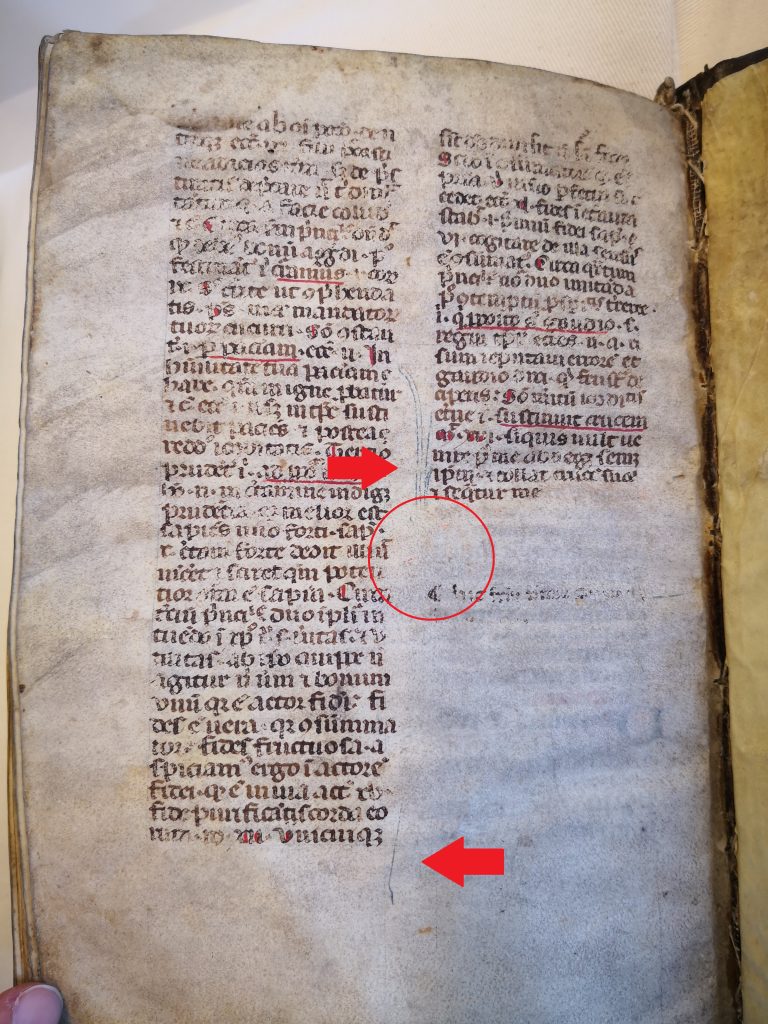

It can safely be assumed that Section 1 (ff. 13-92) is still in its “original” place. It begins the sermons with a historiated initial (and a cute rabbit). The sermons are each introduced by a red and blue flourished initial. What used to be Section 2 (currently ff. 113-136) has been switched with what was Section 3 (currently ff. 93-112). The manuscript description says that two subsequent leaves were inserted (called tipped in singletons) at f. 93 and f. 113. This was probably done to amend the text during the rearranging of the sermons. But as I tried to retrace the movement of the shuffled sections, I just could not see where f. 113 was tipped in. The more I flipped back and forth through the book, the less I understood how it connected to the rest. The folio seemed to exist in a quantum state!

Rather than have a meltdown about it, I should have just realized the obvious: the manuscript description was wrong. Yes, sometimes experts make mistakes too. Folio 113 was not tipped in at all but part of the previous quire. It’s deceptive because of the way it’s cropped around the text. It also used to be the last folio of the book, and, I now believe, originally blank.

Are you still keeping count? Good, so you see the problem. There was still f. 93. You can’t have a single inserted folio and an even number of leaves. It took me literal days of worrying about it to notice that the last leaf of the last quire had probably been ripped out. The final quire is only 11 folia, held together with glue and sheer force of will. Finally, the numbers were adding up. 1 inserted folio + 1 missing folio = an even number. The stars were realigning.

The Text

You know when you are writing an essay, and you think “Actually, this paragraph would make more sense later”, so you just cut and paste it? How do you do that if you are writing on a physical book in the 13th century?

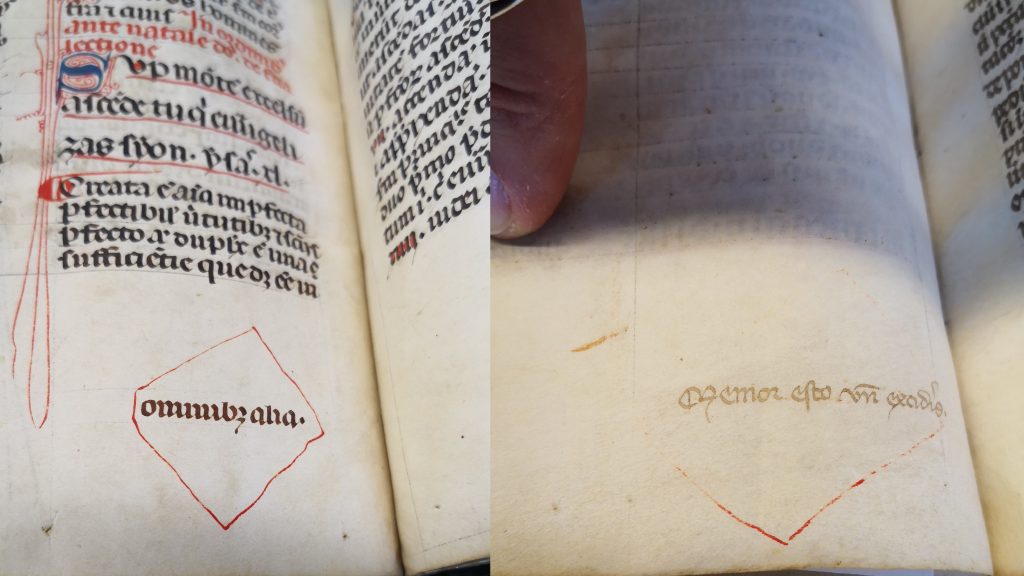

Simple. You just scrape off the text and start over. Parchment is tougher that you think, and it does not absorb ink like paper does. But quill tip, knife, or acid of the ink sometimes leave scars (Clemens and Graham 35; Wellesley 27). And sure enough, ff. 92v and 136v show signs that text has been erased. The remnants of a scraped off initial are visible on both pages. I was willing to bet that whatever was written on f. 136v matched what is now written on f. 93r, but I had no way to prove it.

If only there was a way to read erased text. You know where I am going with this.

No, that’s a sure way to get yourself banned from a library for life. Maybe all libraries.

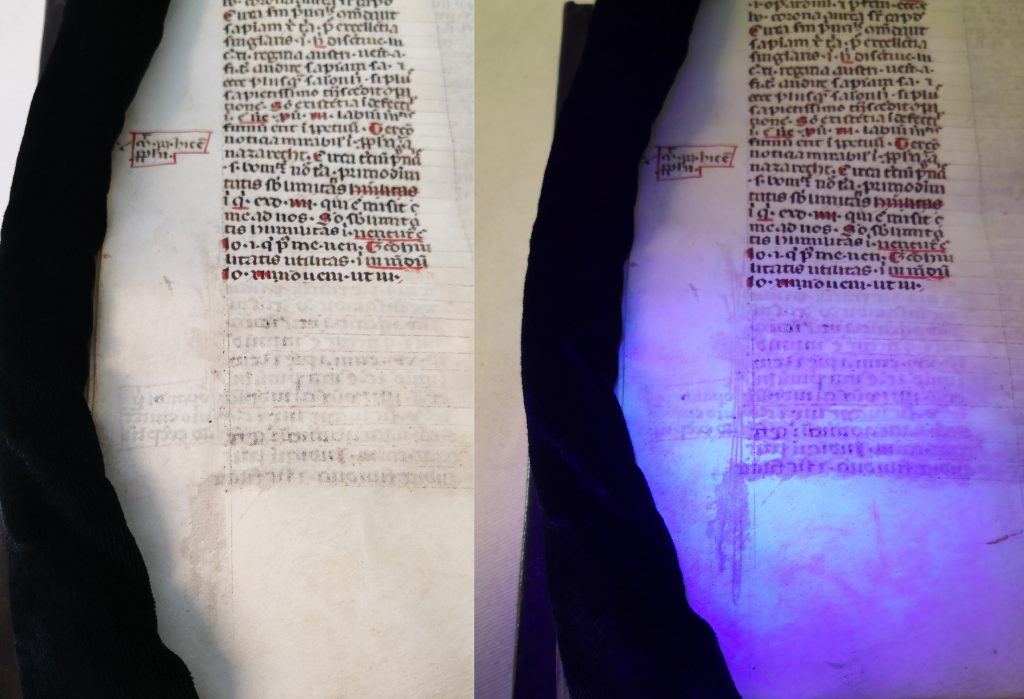

I am talking about UV light!

Now, using UV light does not magically raise a palimpsest. The light merely increases the contrast so that instead of definitely nothing, there is a chance that you might see a very faint something. It turns out you can buy a two-pack on Amazon for $11! What a time to be a manuscript scholar.

This was my moment. I was going to be the first to lay eyes on the manuscript under UV light. I would discover an erased sermon or a scratched out catchphrase that would confirm beyond a doubt the original order of the quires, or a secret code that would lead me to a hidden treasure in the Paris catacombs.

No such luck.

I didn’t really see much at all. Bummer? Not really. While it may feel anti-climactic, it actually told me several things.

- It confirmed much of what I already suspected. Rather than just assuming, I could say for certain that f. 113r was blank.

- The erased initial on f. 136v looked enough like an “M” under UV light to confirm my suspicions. It is not an exact science, and I am no paleographer, but Occam’s Razor dictates that the simplest solution is often the right one. And an “M” is what would have logically followed in the next sermon.

- Whoever did the final reshuffling and editing was very thorough about it. And they went to great trouble to hide their tracks. This suggests some concern about the neatness of the book and the finality of this version of the text.

It also revealed some new mysteries:

- The fact that there was no evidence of an erased catchword on f. 92v is puzzling. The current catchword (matching the new order) is in a different hand/ink. But there should have been a different catchword there originally!

- What was the erased text on f. 92v? If it is the same text currently on f. 113v like I suspect, it must have looked very different. Again, simple math. There are 46 lines of erased text on f. 92v but 67 lines of text on f. 113v. More sophisticated tech could reveal much more, but that’s above my pay grade.

So despite all the dead ends and new questions this experiment has raised, I am satisfied. No one had tried looking at this manuscript under UV light, and at the very least, I can now save them the trouble. Isn’t that the point of discovery? Shining a light (not sorry) so that the next person can continue the work? Even though I did not make the medieval discovery of the decade, it was still discovery, and there is immense joy in that.

Works Consulted

Clemens, Raymond and Timothy Graham. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Cornell University Press, 2007.

Les Enluminures, Ms. TM 868. https://www.textmanuscripts.com/medieval/nicholas-of-gorran-manuscript-91780. Accessed 13 December 2022.

Wellesley, Mary. Hidden Hands: The Lives of Manuscripts and Their Makers. Riverrun, 2022.

Werner, Sarah. Studying Early Printed Books 1450-1800: A Practical Guide. Wiley Blackwell, 2019.