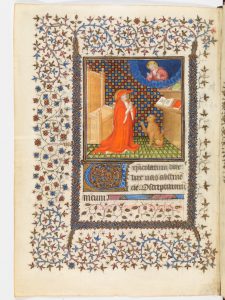

Unlike most modern novels, medieval manuscripts frequently include highly decorated imagery around bodies of text as well as miniatures. Although the choice to include bodies of text with borders and marginal imagery is visually intriguing, they often go unnoticed. In the 13th Century, borders became extensions of the texts they surrounded as an evolution from letter finial to wrapping around bodies of texts entirely. They have since changed to a variety of forms and colors to even containing images within the border itself, however they continued to be viewed passively in comparison. How is it that something could be in such proximity to artistry, yet be devoid of any real praise? The borders and margins of an image suggest that what lies inside their walls is worthy of recognition, while holding a secret power of their own. They never seem to transgress past the point of persistent elegance by demanding more than a polite acknowledgement of their existence. It was not until I began flipping through the pages of the Aussem Book of Hours (MS W.437) that I realized a border could be just as captivating as a sophisticated miniature.

The German Aussem Book of Hours contains stunning and detailed miniatures as seen in Fig. 1. This image found on folio 19.v begins the Hours of the Virgin and contains many different and carefully placed components. The vivid colors of the drapery alone seem to cloak Mary and the angel Gabriel in their encounter as the image is split between the holy dove and a European city in the background. Each miniature in itself is a work of art and a testament to the artist, yet what really captured my gaze were the images in the borders. I became utterly obsessed with the large floral images assembled along the border all together yet completely distinct, as well as the wildlife illustrated in scientific precision. So far in my limited experience, the borders found in the Aussem Book of Hours were unlike any I have seen. I became immensely curious about the nature of borders and what this difference between them could mean.

Before the time the Aussem Book of Hours was published in the early 16th century, certain types of borders were more prevalent. Both the spray and rinceaux appear similarly in their utilization of fine lines with “gilded leaves” (Brown). Spray borders appear as tiny tendrils off the border whereas rinceaux, as seen in Fig. 2, appear as branches with foliage and even fruit protruding from it. The designs created by both the rinceaux and spray borders could be incredibly intricate as the vines are so tightly wound it is hard to distinguish each line, however they do not possess the realistic quality of the foliage in the Aussem Hours. Often the foliage illustrated in the rinceaux and spray are unidentifiable and absent of any real significance in relation to the text it accompanies. In a broad generalization, typically when these borders are utilized they are simply an added touch to the beauty of the manuscript.

In Lucy Sandler’s article, “The Study of Marginal Imagery: Past, Present, and Future,” she traces the progression of borders from decorated or historiated initials to marginal imagery. It is as if the borders sprung from the text themselves and began to literally grow into the margins. The stems of letters became longer and more flourished until they eventually met around the block of text in the center of the page. These new borders were similar to the previously mentioned rinceaux and spray, yet they began to confine the text in sharper lines creating an added separation between border and text. Borders could then contain detailed images such as local flora and fauna in an apparent scattered, or trompe l’oeil, form. This meaning they were deceptively life-like and attempted to appear as they would in nature. Sandler likens the progression to marginal imagery within borders as “a visual response to a verbal—or visual text, altering the totality with images” (1). Her argument gives weight to the power borders possess. In their ability to captivate the audience, they gain control of the reader.

When I began to look at folio 19.v of the Aussem Hours, I noticed my eye followed a spiral progression beginning with the borders until finally reaching the center of the miniature. The more I looked at this image, the more I realized I had no control over my attention. I found myself being lead to a final destination within the image itself that was prompted not by the text or even the miniature, but by the border. The nature of a historiated miniature such as this would suggest that what is being shown in an extension of the text itself or in some way adds to the effect provided by the prayers. The appearance of Gabriel before Mary begins the Matins, which must be said at the beginning of each day. The arrival of each new day is like the arrival of Gabriel before the reader by calling them to begin their liturgical day. When the insistence on attention is drawn away from the miniature to the border, it is a way to undermine the authoritative voice of perhaps the scribe or even the text itself (Camille 22).

In essence the elaborate borders given in the Aussem Book of Hours could shape our initial response upon viewing this text. The images found within the borders are of an earthly nature and scattered as if you came upon them while walking through the wilderness. They directly combat the heavenly encounter displayed within the miniature. The images within the border are also presented with smooth lines and are illustrated in muted pigments, whereas the miniature feels crowded with drapery and bold colors. There then becomes this epic battle for the attention of the reader, where artistic expression trumps textual and devotional response. It is the clash of the familiar earthly world with divine intervention. The borders instantly engage whereas the striking and unfamiliar world illustrated in the miniature might assault the visual senses of the reader. After examining such borders found in the Aussem Book of Hours I feel I have neglected their power, but, rest assured I will not be making that mistake again.

References

Aussem Book of Hours, Walters Art Museum Ms. W.437, fol. 19v

http://issuu.com/the-walters-art-museum/docs/w437/54?e=0

Michelle P. Brown, Understanding Illuminated Manuscripts: A Guide to Technical Terms (J. Paul Getty Museum: Malibu and British Library: London, 1994).

Camille, Michael. Michael Camille. Image on the Edge: The Margins of Medieval Art. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1992.

Sandler, Lucy Freeman. “The Study of Marginal Imagery: Past, Present, and Future.” Studies in Iconography 18 (1997): 1-49. Web.

Utopia, armarium codicum bibliophilorum, Cod. 108: Book of Hours from Paris fol. 139v (http://www.e-codices.unifr.ch/fr/list/one/utp/0108).