So last night I finished up my post about how to teach prayers in a literature classroom, went home, opened my mailbox, and lo! A new issue of Speculum appeared. Serendipitously, that issue includes an essay cluster on “Sound Matters.” “How timely,” I thought, “I bet I could have used this for today’s class.” And I was right. Our class discussion about the voicing of prayer had partly anticipated some of the observations that the essayists made, and could have been enriched by others. So let me make a few links between the essays in this issue and yesterday’s conversation about the aurality of these prayers.

First, we talked in class about how saying a prayer outloud makes it more “real” than simply intoning it in your mind. This is actually a legit medieval concept, for according to medieval philosophers, “it was very clear that the essential matter of words was sound” (Cornish 1015). Voiced words have a material, ontological status that differs from the status of the written word. Alison Cornish goes on to quote and explicate the late classical/early medieval grammarian Priscian: “‘According to the philosophers, vox is “very fine air when it is struck.”‘ The matter of words is voice, or sound; the matter of sound is air that has suffered violence” (1015). If pressed, I suspect we moderns might have taken the opposite track: that writing is the “matter” of words (ink and parchment are visibly material in a way that air and sound waves are not) and voice is the written word’s ephemeral traces. But in the medieval world, where oral interactions still held primacy even after documentary culture became crucial, the hierarchy is reversed; the written word is merely the flat trace of the idiosyncratic materiality of the voiced word, with its inflections and rhythms. (Also note Cornish’s focus on the violence that underpins voice, which is a major theme of her essay on Dante’s Wood of the Suicides. Several of my students have noted the physical violence to animals that precedes the medieval written word; apparently, we can’t escape violence even when we switch to the aural sphere.) This aurality is built into lirturgical or para-liturgical texts like the Hours of the Virgin Mary in ways that may be different from, say, Chaucer’s Legend of Good Women: as Andrew Albin notes, “the text of an [liturgical] office cannot but register its anticipated future residence in the singing voice” (1038). Oral performance is built into the Hours of the Virgin (albeit in slightly different ways than in a full liturgical performance), so in vocalizing the Hours the pray-er helps the text achieve its ideal, material state.

Second, as Susan Boynton suggests in her introductory essay, voice provides a different way of knowing than do words read silently: sound “is central to our experience of the world,” and the interplay of human, nonhuman, articulate and inarticulate sounds (as Sarah Kay fleshes out in her essay on human and non-human song in the troubadour lyrics) create a sonic environment that we traverse with our ears just as much as we navigate the spatial environment with our eyes and bodies (Boynton 1002, 999). In class, we have attended somewhat to the way that praying the Hours affects the body (kneeling, standing, holding the book, crossing onesself), but not to the expanded soundscape in which this somatic prayerfulness would have taken place. Not only the sound of your own voice saying the prayers, but the rustle of clothing and pages, the click of rosary beads that may have reinforced the supra-natural goals of your endeavor — and the dog barking outside, the call of hawkers in the streets, or the child crying in the next room that may have distracted you from that endeavor. The medieval city was a noisy and stinky place, so when we consider the mental and physical habitus that a medieval person would have cultivated for her prayers, we should remember that this habitus was as much protection against distraction as it was devotional focus.

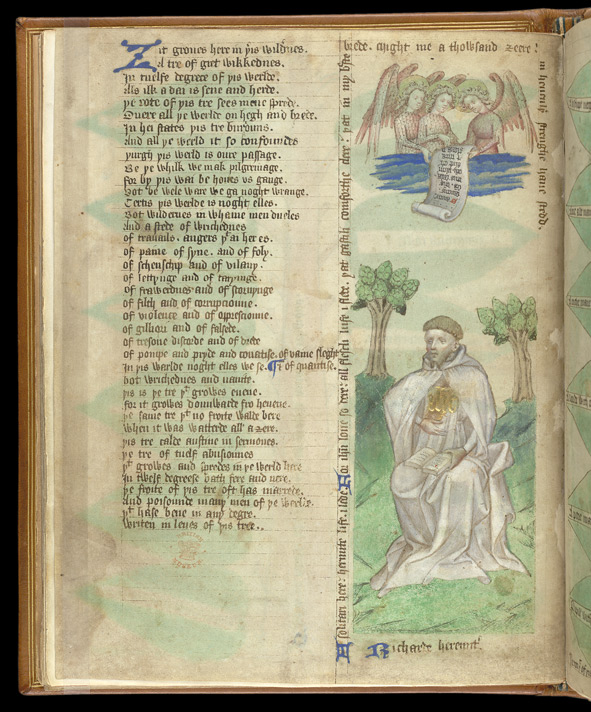

Third, and possibly most fruitful for this course (albeit not in this iteration, alas), is Andrew Albin’s essay on the liturgical offices for Richard Rolle that were sung at Hampole Priory. Rolle was a hermit, mystic, and writer in fourteenth-century Yorkshire who was venerated as a saint (albeit never canonized) in the region, especially at the nunnery of Hampole where his body was buried. Rolle is known for advocating three kinds of transcendent spiritual experience: an inward fire of love; a heavenly sweetness of scent; and canor, which is an internal participation in the music of heaven. You’ll note that these spiritual states are highly physical, which causes some epistemological concerns (do you smell heavenly sweetness with your nose? No, but then why do you call it a scent?), but that’s an issue for another day. Albin traces how Rolle’s concept of canor was problematic for his contemporaries before doing a close reading of the special office (i.e., parts of Matins and the Mass that would have been tailored to the saint of the day) composed for Rolle. That office, he suggests, performs several functions for the nuns of Hampole. Not only does it proclaim Rolle’s saintliness and general awesomeness, as any office would do, but it also accounts for the problems that canor poses: “Rolle’s Officium seeks to resolve the tensions between mystical song’s sensorial immediacy and spiritual loftiness on the one hand, and its devotional potency and extrainstitutional promiscuity on the other, by reimagining what canor is and what it means to hear it inside the more tractable acoustic environment of liturgical singing” (1028). What follows in the article is a masterful reading of the office as text and performance simultaneously, taking into consideration the possible spatial environment in which the office would have been sung. I’d recommend this article to anyone wanting to know how to “do” close reading of liturgical text-as-performance (something I’ve attempted now and then, and it ain’t easy).

Most valuable for our class right now is Albin’s discussion of the way that singing the office mucks about with space and time:

Importantly, the inosculation of person, space, and time that Lesson 6 [from Matins in the Officium] and its responsory promote can only occur in the resonant acoustic space and time of liturgical performance. In singing the office, blurry boundaries inside and outside the lessons’ narrative diegesis come into alignment: where chapel and cell, where celebrant and saint, where chant and canor end and begin becomes difficult to pin down. (1034)

This is very like the analogic temporality, as we’ve discussed in class, that the pray-er enters into when speaking (for example) the lamenting words of Job in the Office of the Dead, wherein she voices simultaneously Job’s words, the words of the tormented souls in Purgatory, her own words now, and her future words as a tormented soul. In the Hampole office, that temporal blurring is enhanced by the way the office invokes canor, but it still obtains in the relatively simpler sonic environment of the Office of the Dead. Note Albin’s spatial language (“inosculation” is a kind of natural grafting) that draws attention to the fusion of the heavenly and earthly song within the space of the church, whereas we have been primarily discussing the movement and fusion of times.

How far would the prayers in a Book of Hours been voiced? I have been presuming that one would say them aloud, but I realize that I have only a few clear reasons for doing so. Certainly the directions for the anchoresses in Ancrene Wisse Book 1 presume vocalization of all their prayers, and the “Instructions for a Devout and Literate Layman” tell him exactly what to “say” (presumably aloud) at different moments of the day, in distinction to other times when he is encouraged to be silent or to “ruminate in your mind” on spiritual concepts (Pantin 399). But these are prescriptive, not descriptive texts. Did medieval people truly say their Hours aloud? I suspect they did, but would love clear evidence to support that.

Andrew Albin, “Sound Matters: 4. Canorous Soundstuff: Hearing the Officium of Richard Rolle at Hampole.” Speculum 91.4 (2016): 1026-1039. You may be able to access this issue, if you are on the UGA campus, via http://www.journals.uchicago.edu.proxy-remote.galib.uga.edu/toc/spc/2016/91/4.

Susan Boynton, “Sound Matters: 1. Introduction.” Speculum 91.4 (2016): 998-1002.

Alison Cornish, “Sound Matters: 3. Words and Blood: Suicide and the Sound of the Soul in Inferno 13.” Speculum 91.4 (2016): 1015-1026.

Sarah Kay, “Sound Matters: 2. The Soundscape of Troubadour Lyric, or, How Human is Song?” Speculum 91.4 (2016): 1002-1015.

William A. Pantin, “Instructions for a Devout and Literate Layman,” Medieval Learning and Literature: Essays presented to Richard William Hunt, ed. JJG Alexander and MT Gibson (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1976), 398-422.