Imagine that your favorite author of all time has decided to release a suuuper special edition of their most famous work, in collaboration with a new publisher. They promise that it will be the best version of their most famous work, you know, the one that the influencers keep taking pictures with on Instagram. You immediately think, “I have to get this. OF COURSE, I am buying it, no matter how many extra shifts I have to work to afford it.”

Let’s fast forward to you walking into your local bookstore. You see the book on display, and from the outside, it looks like everything you think it would be. You flip through the first pages, reading the preface, promising that your next few hours of reading are going to be epic. You buy the book, and begin reading through the chapters, only to realize… there is a huge misprint that throws the entire structure of the book off, the pictures in the story are continuously repeated, and it is just plain old boring. You are filled with disappointment as you have sacrificed your Starbucks money for this. You have just been catfished.

This may have been the reaction of medieval readers who acquired William Caxton’s second edition of Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales.

For context, William Caxton was a famous printer, known for setting up the first English printing press, according to The British Library. With royal clients from all over, he was successful up until his death in 1492. Caxton was essentially the father of the English printing press and had a niche for printing in English. As the first person in his field, one would think that his skills were expert level. This proved to be false, as he botched one of the most famous texts during this time. So, what made this text so flawed?

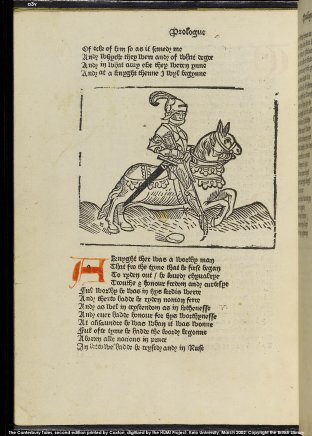

When receiving the book, medieval royals were probably excited to open this highly popularized book of Chaucer’s poem. Though, if they turned through the pages carefully, they could see the blandness and carelessness within the text. From cooked woodcuts and the misprint seen during “The Reeve’s Tale” on folio 69v, which completely interrupts “The Cook’s Tale” without warning, a royal buyer could see that this mass-produced text was not of the highest quality. To make matters even worse, the words on the folios themselves were printed crookedly.

Now, I know what you are thinking: If this is the case..then how did he sell it?

False advertising.

Caxton took matters into his own hand wrote his own preface to provide a backstory to why he was making a new version of the text he had already printed. His “Prohemye”, on folio 2, explains why this edition came to be. He writes that he was approached by a gentleman who claimed that his father had a manuscript that was the closest to Chaucer’s words. Caxton took his word for it, and his criticism and decided to print the second edition based on the manuscript he was given.

Why would Caxton trust this random guy and take his word that he had Chaucer’s most accurate version of the text? Easy. money.

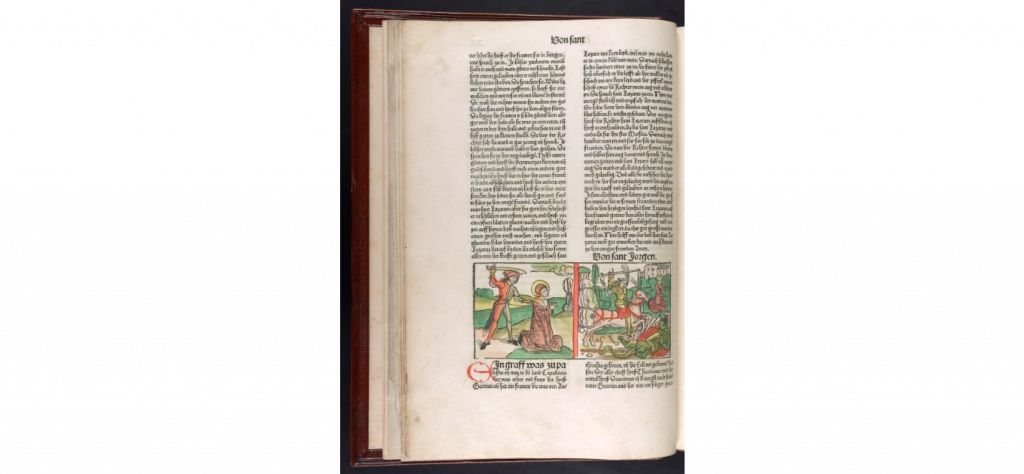

This made me wonder what medieval royals would have expected from someone of Caxton’s caliber. A great example of this would be this book of the lives of saints called Passional, das ist Der Heyligen Leben.

This text was written by Jacobus de Voragine, and printed by Anton Koberger Nuremberg. With its creation in 1488, Nuremberg’s print is full of colorful woodcuts of saints. The Passional mimics the layout of the Canterbury tales, with two columns of text. The text is carefully printed across the page. The woodcuts contain beautiful colors and fine lines that depict the images of saints. The Passional has headers that separate the text sections correctly and precisely. The attention to detail, and the reverence for this text full of holy figures is clearly reflected through this edition of print. Medieval patrons would have been pleased with investing their funds into something so beautiful. Clearly, this is not what they received with Caxton’s second edition.

This made me wonder, how did he so cleverly bamboozle his prestigious customers?

William Kuskin, in Symbolic Caxton: Literary Culture and Print Capitalism explains it this way, “Thus, Caxton brings Chaucer to market as both tangible commodity and an intellectual abstraction, an embodiment of capital investment that can be appropriated by his readers. In doing so, he transforms this culture by teaching a new generation of readers how to profit from literary authority” (Kuskin 137). Meaning: Caxton essentially created a medieval catfish in the form of a text. The second edition, at first glance, reflects Chaucer’s authority. Through the mistakes in the text, we can see that this mass printed text sheds a bad light on Chaucer and his famous words. And much like the ways of current greedy businessmen in our society, Caxton, got away with it. (Anna Engle also speaks about how modern readers would have received Caxton’s second edition in her blog post, which can be found here). Caxton becomes the father of a capitalism centric system that is focused on producing wealth for himself.

Works Consulted

Chaucer, Geoffrey, The Canterubury Tales. London: William Caxton, 1483. British Library. https://www.bl.uk/treasures/caxton/record.asp. Accessed November 12, 2021.

De Voragine, Jacobus, Approximately, et al. Passional, das ist Der Heyligen Leben. Nuremberg, Anton Koberger, 5 Dec. Freitag vor Nikolaus, 1488. Pdf. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, Image 24 of Page view | Library of Congress (loc.gov). Accessed November 12, 2021.

Kuskin, William. Symbolic Caxton: Literary Culture and Print Capitalism. University of Notre Dame Press, 2008.

Wight, C. “Caxton’s Chaucer – Background to William Caxton’s Life.” The British Library. The British Library, 19 July 2004, https://www.bl.uk/treasures/caxton/background.html . Accessed November 12, 2021.