The Dorothy du Rant diary is exactly what it says in its name; a diary. Filled with the memories and words of young Dorothy du Rant, presumably in her early teen years, in 1912, this text brings its readers back to the thoughts of Ms. du Rant. Struggling with the day-to-day life of womanhood, the reader of this diary gets to experience their younger years again, following Ms. du Rant through the trials of multiple crushes, a strict mother and family life, and the pressures of being a young girl at this time. Given the content of the diary, the reader can presume she is in her early teenage years, roughly 16 or 17, upper to middle class, and, seemingly, from the south considering the addresses on the back of the diary. From school to forced violin practice, readers can see how it felt to be a young woman during 1912, societal pressures included.

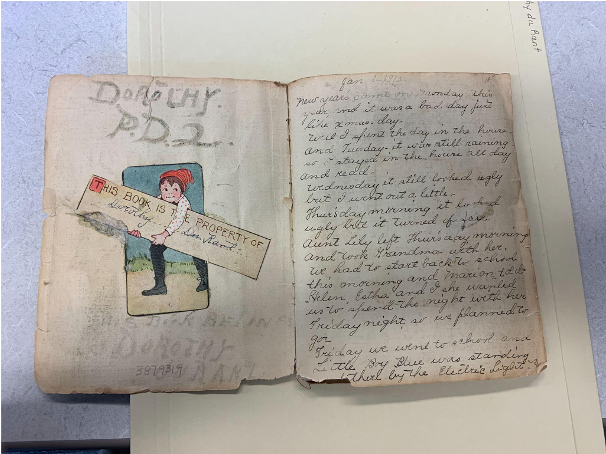

Dorothy du Rant Diary, ms3640, leaf number 1, photo taken by Kenzie Muenzer

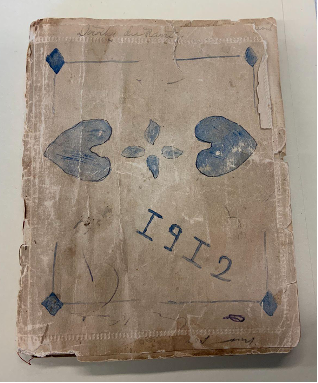

The diary itself is small, only 6 ½ inches by 5 ¼ inches, and only ¼ inch thick (this is equal to the size of a large passport holder). It is hand-sewn and clearly handmade by Ms. du Rant, herself. There are multiple gatherings nested within one another, although loosely held together now due to wear-and-tear. On the outside, you can see the red stitching that shows it’s been hand-sewn. Readers can also tell its handmade from the multiple types of paper throughout, including notebook paper and various thickness levels of cardstock. She uses multiple types of ink throughout. However, whether she writes in pencil or pen, she continues to write in cursive English script, with some specific idiosyncrasies in her capital H’s and lowercase T’s.

Dorothy du Rant Diary, ms3640, front cover, photo by Kenzie Muenzer

Given that this is a diary, the purpose and function of the object are hard to determine. To understand the purpose of this object, we have to ask ourselves why anyone would want to keep a diary or journal. The act of journaling has been linked to being beneficial in mental health (Purcell), but I think, from the subject matter of the diary, that diary was meant to be a general recollection of teenage memories. She discusses her day-to-day activities in detail and often includes mentions of her many crushes, typical of a young girl’s diary. According to Textual Boundaries: Space in Nineteenth-Century Women’s Manuscript Diaries, “as women diarists show, the spatial world of women’s separate sphere gave women support during the recurring life cycle of events that regularly punctuated a woman’s daily existence” (Huff 124). In reference specifically to Ms. du Rant, we must ask ourselves “do diarists write for their own eyes only or for a yet unknown and maybe hoped for reader?” (Gristwood 3). I argue that given the contents of the diary and its handmade nature, Dorothy du Rant didn’t intend for anyone to read it. However, with inclusions of code names for her peers, especially those of her previously mentioned crushes, such as “Little Boy Blue” and “Mr. Spiderwebb”, I would understand if she assumed someone, such as her mother who enforced the strict societal standards of the time on her, might read it. These code names are clearly for her “protection” and peer’s anonymity. In this way, I don’t think Dorothy’s diary has a function outside of the one we, as her unknown audience, now prescribe to it, and the function we prescribe relates to the value in society.

Why do we cherish objects such as Dorothy’s diary? I assert that it begins with the familial value attributed to the text. We find objects that once belonged to family members and add value to them because we miss them or are curious what their life was like in comparison to ours, especially in the case of young women. It gives descendants an idea of what society was like when their predecessors walked the earth; did they have the same pressures as us, or was their life vastly different than ours? There are various reasons for this familial value. However, after this comes the applied cultural value. Going back to Textual Boundaries, Huff says in reference to another diary, “space is socially and culturally constructed and reflects our ideas about how we interact within a culture and how that culture influences us” (Huff 123). The space she mentions is in direct relation to diary and journal writing. As Ms. du Rant writes, she is including her audience into her social and cultural constructs, which translates to us as cultural influence and value. Huff goes on to say:

nineteenth-century British women’s manuscript diaries are just such an ideological site of contestation, a space where the gendered interpretations of true womanhood meet. If, on one hand, they reinforce and confine women within the strictures of the masculinist beliefs of the lady, their structure is likewise loose enough to accommodate a woman’s self creation (Huff 125).

In this way, women’s diaries, culturally, serve to show us perspective into the oppressed lives of women, given that this was their only form of “self-creation”. With Ms. du Rant’s diary, especially since it was handmade, we can see the “self-creation” Huff discusses in her essay. With her pastedowns, drawings, assorted poems, and more, this diary is a reflection of Ms. du Rant’s sense of self.

Despite what appears to be just a teenage girl’s frivolous diary documenting her naivety, we can learn much from her experiences growing up. I believe this is why we attribute value to diaries and journals, as compared to mass-produced texts. Unless given as a gift, we don’t know how to add that familial value to mass-produced media, at least not in the same way we can from journals like Ms. du Rant’s. Until we learn, that novel sitting on your coffee table will continue to act as a coaster with condensation rings until you replace it with the next coaster. Journals simply won’t.

References:

Bunkers, Suzanne L., et al. “Textual Boundaries: Space in Nineteenth-Century Women’s Manuscript Diaries.” Inscribing the Daily: Critical Essays on Women’s Diaries, University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst, 1996, pp. 123–138.

Dorothy du Rant diary, ms3640, Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, The University of Georgia Libraries.

Gristwood, Sarah. Recording Angels: The Secret World of Women’s Diaries. Harrap, 1988.

Purcell, Maud. “The Health Benefits of Journaling.” Psych Central, Psych Central, 17 May 2016, https://psychcentral.com/lib/the-health-benefits-of-journaling#1.