Throughout this section, there has not been one defining moment that has opened the gates of understanding about the book of hours for me. However, if I had to pinpoint one particular topic that I think is extremely important when learning about the book of hours, I would say it is the concept of time. Time is present throughout the book of hours, both literally and figuratively. The more we continued to discuss time in all of its different fashions, the book of hours became easier to understand with time’s incorporation.

The three separate denotations of time that need to be discussed are linear, analogical and institutional time. All three types played keys roles within the book of hours, as well as in church in general. Linear time is the view that time passes forward throughout a person’s life. This concept of time would entail birth, life and death. Analogical time is associated with astrology. An example of this passage of time can be found in the calendar within a book of hours. On a calendar page, the reader would find in one column “the golden numbers”. These numbers would help the reader calculate the phases of the moon, which would in turn help them find the day of the year for Easter. Institutional time was church time. This would be when to pray, and as discussed earlier, the hours the monks would follow.

In its most literal sense, the subject of time played several roles within the book of hours. When a book of hours was created, there were several moving parts to it. There were several individuals who had a hand in putting the book itself together. Because of this, the book itself was extremely important to the owner. Because of its value, books of hours would often times have specific times and dates written in them that were important to the family. Out of all of the information that I learned pertaining to the book of hours, the concept of families writing important dates in the book resonated with me the most. My great grandmother had a 19th century family bible she kept that had important family dates in them. This bible had been in my family for sometime; it contained birthdays, deaths, and even wedding anniversaries. After learning that the owners of books of hours did the same thing my great grandmother did, it made the importance of the book a little easier to understand. In addition to writing dates, gifting books of hours at events such as weddings or christenings became popular. Over time, these texts would be passed down through a family so the traditions and the book itself would retain the familial provenance that was written within it. Because of the book’s bequeathment through generations of a family, the denotation of time in regards to the creation and possession of the book would be linear.

In chapter 13 in Introduction to Manuscript Studies, the author delves into the explanation of the title of the book of hours itself. It says “The “hours” alluded to were of course the hours of the monastic Divine Office; the times of day at which monks gathered in church to pray” (Clemens, Graham, 208). The “hours” of mention were broken up into 8 sections: matins, lauds, prime, terce, sext, none, vesper and compline. The daily routines of the monks revolved around prayer. They would wake up and pray, pray before they went to bed, and prayed several times in between. This was another interesting topic to uncover. Being religious, I do my fair share of praying; but it is amazing to observe the incredible amount of piety the monks displayed. It is much easier to accept and understand an idea, like their praying, when it holds personal meaning. It should be said that most common people could not adhere to this stringent prayer regiment because of their jobs. While they had to go to work, most people did try to stick with the prayer schedule as best as their job would allow. The time of prayer for monks and congregation is referred to as institutional time.

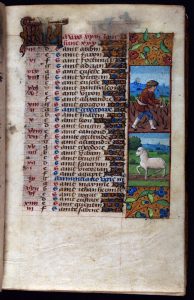

The calendar that is found in the front of books of hours is incredibly important. Chapter 12 in Introduction to Manuscript Studies explained the role of the calendar best. It says that “The calendar served a most important purpose by providing a swift and easy means of ascertaining which events in Christ’s life and which saints were being commemorated on any given day of the year” (Clemens, Graham, 194). The role of keeping time and important dates was critical for a reader to have in their book of hours. The calendar aided its owner in keeping track of all the events within a year of the church. The calendar is unique in that it is comprised of all three denotations of time. The calendar traced through a whole entire year, which would be linear time. The calendar’s far right column identified holidays and commemorative days within the church, representing institutional time. Finally, “the golden numbers” represented analogical time by supplying the moon phases in order to figure out the day of Easter.

Another literal representation of time within the books of hours was its availability.

When books of hours were beginning to be created in the 14th century, they were highly sought after and were highly expensive. Because of this, only the exceptionally wealthy could afford to have a book of hours made for themselves. However, after moving through the 15th and into the 16th century, printing became widely available so the cost of the books ended up decreasing. Throughout the course of time the book of hours was able to become widely available to anyone that wanted it.

Being a part of such a fast paced world, I really do not take into consideration the “big picture”, but rather take one day at a time. It is quite interesting to think about applying institutional or analogical time to my life; as opposed to just linear time. I know I found it hard to comprehend, but learning about time broadened my views of time as more than just an intangible concept.

Clemens, Raymond, and Timothy Graham. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 2007. Print. Chapter 12, page 194. Chapter 13, page 208.

image url: https://www.flickr.com/photos/dplmedmss/8644604528