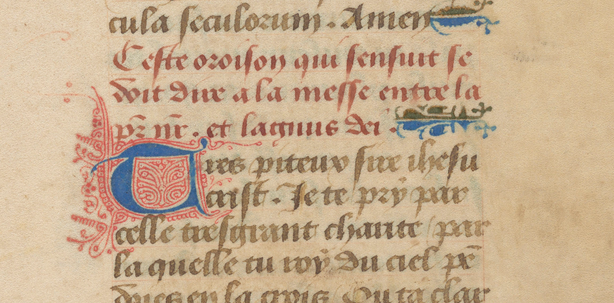

The Hargrett Hours’s French prayer that runs from folios 54r through 55v (and which I will refer to as “Tres piteux sire”) has been one of the manuscript’s most challenging yet fascinating passages to work with. Below is a transcription of the original text and an English translation produced by the 2016 and 2018 teams and edited by Dr. Catherine Jones and Dr. Jan Pendergrass of the UGA French Department:

Ceste oroison qui s’ensuit se doit à dire à la messe entre la pater nostre et l(’)agnus dei. Très piteux sire ihesu crist. Je te pry par celle trèsgrant charité par la quelle tu roy du ciel pe(n)doies en la crois Où ta clarté deifiée, où ta très debonaire âme, ta manière si triste si piteuse, tes sens troublez, ton doulz cuer transfiché, ton corps trespercié, tes plaies ensanglantées, tes mains espandues, tes venes Estandues, ta bouche cria(n)t, ta voix enrouée, ta face pâle, ta couleur mortel, tes yeulx plourant, ta gorge gémissant, tes désirs sou lans, ton goust amer de fiel, ton chief encliner, ton corps de ton âme deviser, vive fontaine courant de ton coste. Par celle très grant charité très amant sire, je te pri par celle charité en la quelle estoit enstraint to(n) très amoureux cuer que tu me soie piteables en moi p(ar)donnant la très grant multitude de tous mes pechiez. Et me vueilles donner bonne finz saincte et glorieuse résurreccion en ta saincte compaingnie par ta très grant miséricorde. Amen.

This prayer that follows should be said at mass between the Pater Noster and the Agnus Dei. Very piteous Lord Jesus Christ. I pray to you through this very great charity by which you, King of Heaven, hung on the cross, where your godly brightness, where your very good-natured soul your manner so sad, so piteous, your troubled senses, your soft heart pierced, your body stabbed through, your bloody wounds, your hands spread, your veins distended, your wailing mouth, your voice become hoarse, your pale face, your deathly color, your crying eyes, your throat moaning, your desires fatigue-inducing, your taste bitter from venom, your head bending down, your body divided from your soul, living fountain running from your side. By this great charitable act, very loving Lord, I pray to you through this charity in which was enstraint your very loving heart that you be merciful in pardoning me of the great multitude of all my sins. And please give a great holy end and glorious resurrection in your holy company through your very great mercy. Amen.

My experience with this prayer came from being a part of the 2018 course’s “Team Prayers,” whose primary goal was to finish transcribing the seven accessory prayers found in the Hargrett Hours and to do more research into their provenance and historical context. While most of the Latin prayers were able to be identified elsewhere, the primary difficulty that the French text poses is its uniqueness; neither we nor the previous team have been able to locate it in any other manuscript. As the only team member with a background in French, my primary role was to investigate further whether or not the prayer is truly unique to the Hargrett Hours and what larger implications this uniqueness might have (both for the prayers section and the manuscript as a whole).

Although I didn’t have much experience with Middle French, the first time I read through the prayer in the original I was still able to gather that it discusses the Crucifixion and that it is addressed to Jesus; however, in order to have a better understanding about the prayer’s content, I decided to work on developing my own translation, a process that was both frustrating and rewarding (sort of like solving a puzzle would be). As I started putting the “pieces” together and making new discoveries, what I found most striking was the sheer beauty of this prayer’s language. As the translation above reveals, the prayer’s depiction of the Crucifixion is extremely emotive and descriptive.

Through my experience with the prayer, I started to become intrigued less by the question of whether the prayer exists in any location and more by how its powerful language and rhetorical moves make it unique from other prayers in Books of Hours. At this point, we can only conjecture what its origin might have been; a book owner could derive an accessory prayer from a myriad of places, such as from other prayer books, their parents, or clergy members (Reinburg 18). But even if we can’t determine its origin or the exact identity of the Hargrett Hours’s owner, examining the prayer’s language provides a window into how the text functions as a devotional aid within this particular manuscript. We cannot assume to know the actual devotional “experience” of an individual living in another religious culture (Reinburg 137). Still, considering the rhetorical and linguistic features of “Tres piteux sire” illuminates the type of affective experience that it is inviting, which in many ways, as I will show, makes it stand out from other French prayers found in medieval Books of Hours.

“Tres piteux sire,” which is the fourth prayer out of the seven found in the Hargrett Hours, stands out in a few major ways from the other six. A common theme that runs throughout these prayers is the Passion of Christ; for example, the first three prayers particularly focus on the Crown of Thorns (further supporting the theory that the Hargrett Hours can be connected to “Sainte-Chapelle,” a thirteenth-century chapel that housed the holy relics), while the fifth discusses the blood of Christ as a “comfort object.” (These details further support the 2018 team’s theory that the Hargrett Hours can be connected to Sainte-Chapelle, a thirteenth-century chapel that housed the holy relics.) But the most immediately obvious difference is the fact that it is written in French and not in Latin, the language of the other six prayers. Although Latin was originally the dominant language found in Books of Hours, it’s not completely unexpected to find a vernacular text. As Reinburg explains, “even the earliest books of hours included some French,” such as rubrics and occasionally a few full texts (96), and by the beginning of the sixteenth century, most Books of Hours from France “were Latin – French hybrids” (99).

Nevertheless, even if it isn’t particularly strange to encounter a mix of Latin and the vernacular, the fact that “Tres piteux sire” is in French and that it is placed as the fourth prayer situates it as the very centerpiece and focal point of the accessory prayers section. In fact, even though the Passion is significant throughout the prayers, none is quite as graphic and descriptive of Christ’s suffering as the French prayer is. Thus, the very fact that the language of this prayer is different from the rest draws the reader’s attention and emphasizes the scene of the Crucifixion, which might have had a special importance to the owner of the Hargrett Hours. The research from the 2018 team working on the Gospels section of the Hargrett Hours suggests that the owner could probably “comprehend the meaning of Latin texts,” but the fact that the prayer is in the vernacular creates a sense of intimacy between the devotee and Christ. Instead of using the language of the church, the speaker uses the tongue that they would be more likely to use at home, lending to a degree of familiarity, which allows them to take charge of their own devotional experience and partake in a very personal engagement with Christ.

In addition, not only does the speaker feel comfortable using the vernacular, but he or she also uses the familiar “tu” instead of “vous.” He may be the divine “King of Heaven,” but He is also a relational God. This familiarity (though still used with a tone of respect) is especially significant given the fact that the prayer is centered on the Crucifixion, as the entire reason for Jesus to come to Earth and die on the cross was to provide humanity with access to the Father and eternal life with God.

Further, the fact that the text addresses Christ directly is significant because this feature, although not completely unique, was not the norm. For instance, during my research I read through an appendix that Victor Leroquais created in 1927 of sixteen French prayers in Books of Hours held at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, and only two, which include the “Prière pour l’élévation” (from Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS lat. 1179, f. 150v) (Leroquais 322) and the “Prière à Jésus-Christ” (from Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS lat. 1161, f. 1r) (Leroquais 323-324), are addressed directly to Christ. In Books of Hours, in which the Virgin Mary typically takes the central role, “most prayers were intercessory,” as devotees would ask her “and the saints . . . for their intervention before God, and in exchange offered them praise, tribute, or donations” (Reinburg 4).

This feature, then, further adds to the prayer’s emphasis on a personal relationship with Christ. The object of the prayer is essentially Christ Himself, and beyond asking for pardon for his or her sins, the speaker does not make many petitions or requests, nor does he or she offer tributes or donations in exchange for blessings. The prayer, it seems, seeks both to orient the devotee’s mind on praising and honoring Christ for His sacrifice and to participate in a relationship with Him that this “act of charity” afforded. Thus, the prayer functions as a tool for meditation, encouraging the devotee both to exalt and seek unity with Christ. Moreover, this positioning of Christ in familiar terms and as a man, both fully God and fully human, only makes his suffering that much more harrowing.

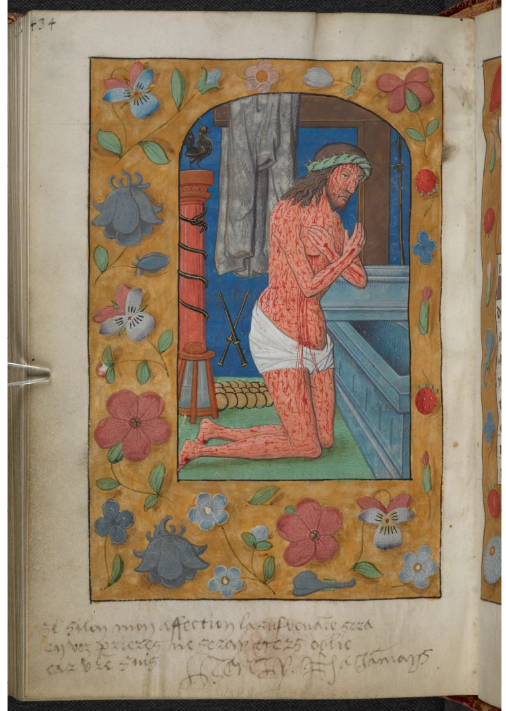

The emphasis on the dual, divine-human nature of Christ is also central to the prayer because it allows the devotee to join in the physical experience of Christ (or, at least, to imagine this experience through its verbal representation on the page). This technique is primarily achieved through the manner in which the text lists each aspect of Christ’s physical appearance as He was dying on the cross; for instance, the text reads: “your manner so sad, so piteous. Your troubled senses, your soft heart pierced, your body stabbed through, your bloody wounds, your hands spread, . . . your wailing mouth, . . . your pale face, your deathly color, your crying eyes, your throat moaning, . . . your taste bitter from venom.” Although medieval practices of punctuation were different than those used today, the use of asyndeton (the lack of conjunctions) speeds up the pace of this section and heightens the sense of anxiety as the speaker imagines Jesus’s pain during the Crucifixion, and this extensive list overwhelms the devotee with the multitude of ways Christ must have been suffering emotionally and physically all at once.

Moreover, this description is also so effective in transferring the pain of Christ to the devotee because it appeals to multiple senses. Not only can the effects of Christ’s torture be seen, but they can be heard (e.g., “your wailing mouth” and “your throat moaning”) and even tasted (“your taste bitter from venom”). Thus, despite initially positioning Christ as the “King of Heaven,” the text is just as concerned with the physical pain He felt in the body of a man. The speaker is thus better able to sympathize with and appreciate this “act of charity” because the experience of Christ is displayed in corporal terms.

The function of these rhetorical and linguistic features are not only “affective” but also cognitive. Medieval authors employed a variety of complex mnemonic techniques within their written texts, sermons, and manuscript pages. One strategy by which they attempted to imprint their message on a reader or listener’s mind was through the use of especially graphic and emotive images, as Mary Carruthers describes:

Because the memory retains distinctly only what is extraordinary . . . and intensely charged with emotion, the images should be of extremes – of ugliness or beauty, ridicule or nobility, of laughter or weeping, of worthiness or salaciousness. Bloody figures, or monstrosities, or figures brilliantly but abnormally colored should be used, and . . . engaged in activity of a sort that is extremely vigorous (166-167).

The image of Christ in this text may not be a “monstrosity,” but it is certainly “intensely charged with emotion,” especially when compared with other depictions of the Crucifixion in French prayers. Neither of the two prayers found in Leroquais’s appendix that are addressed to Christ go into the same amount of detail in describing His appearance, making this prayer unusual not only in the sense that it is addressed to Christ instead of Mary or the saints but also in its particularly intricate and impassioned portrayal of His death.

The effect of this deeply emotional representation of Christ’s pain is that the prayer invites the devotee to create a mental image in his or her mind; in fact, reading a text “was considered to be essentially a visual act” (Carruthers 20). Considering the fact that the Hargrett Hours contains no miniatures (though it’s possible that miniatures originally existed and are now lost), this visual component of reading becomes especially significant. Further, this “visual form of sense perception is what gives stability and permanence to memory storage” (19). The impact that the prayer has on the devotee operates not only in the moment that it is being read or spoken, but the intensity and emotion that are present function as a way to make a lasting impression on his or her mind.

Mark Amsler also talks about the importance of visual and sensory perception in another devotional guide book from the Middle Ages, the Ancrene Wisse, and I think his analysis jives just as well with the type of spiritual experience “Tres piteux sire” is inviting. In the Ancrene Wisse, texts are more prominent than images, but he argues that the book “gathers together various intentiones of the anchoress’s eyes, ears, and mouth as she reads aloud or silently” (88) and encourages the reader to focus “her senses on an external material object, the verbal and pictorial signs on a page, in order to incite her affectio” (89). Similarly, the emotive and sensory imagery in the text of the Hargrett Hours’s French prayer is acting in the place of a visual aid on the page. The “external material object” on which the devotee is encouraged to focus is the very body of Christ, and the speaker is transported to the scene of the Crucifixion as if it were occuring before his or her eyes.

And this cognitive function leads me to one final point about the prayer’s rhetoric I find particularly fascinating. Most of my research in medieval literature has focused on allegory (which is, in fact, the subject of my master’s thesis), and although this prayer isn’t necessarily “allegorical,” the effect of this engagement between the reader and the text reminds me of a concept called allegoresis. Rita Copeland and Stephen Melville argue that medieval authors used allegoresis as a sort of rhetorical move by which the responsibility of interpretation and “intentionality” of their writing is shifted to the reader (179). In a similar process, the use of sensory and emotive imagery in the text of “Tres piteux sire” encourages the devotee to internalize and interpret the Crucifixion for him- or herself. The words of the prayer may provide the script, but its ultimate effect occurs within the mind of the devotee. In this sense, the individual reading the prayer takes on the role of the exegete, and these “verbal and pictorial signs” on the page and the appeal to multiple senses act to shift both the meditation of the Crucifixion as well as the sensory experience to the devotee through the process of a sort of “affective” allegoresis.

Thus, the language and rhetoric of “Tres piteux sire” operate on both a sensory and cognitive plain. The prayer seeks to inspire the reader to partake in an intimate and personal engagement with Christ. By emphasizing the pain of Christ’s death, the text encourages the speaker not only to contemplate the physical suffering of Christ but also to feel it. Together, the uniqueness of the prayer, the use of the vernacular tongue, and the particularly emotive description of the Crucifixion sets this prayer apart from many other French prayers of the period and leaves a poignant and compelling impression on the reader or speaker’s mind. The words of the prayer may be beautiful and powerful in themselves, but their ultimate effect (and affect) is only realized through a complex mental and emotional process on the part of the devotee.

– Savannah Caldwell

Works Cited

Amsler, Mark. “Affective Literacy: Gestures of Reading in the Later Middle Ages.” Essays in Medieval Studies, vol. 18, 2001, pp. 83–110.

Carruthers, Mary. The Book of Memory: A Study of Memory in Medieval Culture. Second ed., Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Copeland, Rita, and Stephan Melville. “Allegory and Allegoresis, Rhetoric and Hermeneutics.” Exemplaria, vol. 3, 1991, pp. 159–187.

Leroquais, Abbe V. Les Libres D’Heures: Manuscrits De La Bibliothèque Nationale. II, Bibliothèque Nationale, 1927.

Reinburg, Virginia. French Books of Hours: Making an Archive of Prayer, c.1400–1600. Cambridge University Press, 2012.